A Dreadful Anniversary: May 31, 1921 (Tulsa, Oklahoma)

*/ /*-->*/

Tulsa’s black community was prosperous in the first decades of 20th century. There were restaurants and theaters, and a shopping district offered fine goods. The African American press of Tulsa called Oklahoma “The Promised Land.”

As the Topeka Plaindealer put it on May 28, 1915:

“There are seven good churches, and the schools are among the best in the state. Numerous rent houses are owned by the race, and they are indeed excellent ones. Many brick buildings, and business enterprises are owned by the race. There are about 4,000 colored citizens, and all in all we are pushing ahead.”

And then came the infamous and perhaps misnamed Tulsa race riot of 1921. It’s not really a riot when hundreds invade a neighborhood, loot homes, shoot people, and set the place on fire. When contemporary papers called what happened in Tulsa a race war, they weren’t exaggerating. This is what happened on Memorial Day, 1921: A black shoeshine boy entered an elevator run by a young white woman. She screamed. He ran. Police are called and a sexual assault is presumed by others. The boy is arrested the next morning. The afternoon Topeka paper reported this and published an editorial entitled “To Lynch Negro Tonight.” A white crowd in the hundreds gathered before the county courthouse. A group of armed blacks arrived and made an offer to help guard the prisoner. In 1919, just such a group had helped prevent a lynching.

Rebuffed by the sheriff, they returned to Greenwood, a prosperous black neighborhood in Tulsa. The white crowd around the courthouse increased. A second group of armed blacks arrived and offered to help prevent the anticipated lynching. They are turned away. This time someone tried to disarm one of them. Shots were fired, probably accidentally. The return fire was not. The blacks retreated under fire. The whites tried to break into the armory and are prevented from doing so. So they broke into sporting goods stores and grabbed weapons and ammunition. Then the whites tried to invade the prosperous neighborhood, but were stopped by armed residents. A passenger train that drove through Greenwood was shot up by both sides.

Blacks began to flee the neighborhood. The battle at the tracks died down in the early hours of June 1. Some might have thought the fighting was over. White crowds continued to congregate on the edges of Greenwood. When the early dawn came, they attacked from several locations. A machine gun on top of a grain elevator controlled one main street. Airplanes flew overhead. Those in passenger seats fired down at the blacks below them. It is alleged that they dropped firebombs on the neighborhood. Whites would enter a home, loot it and then torch it. If the home had a gun, they would shoot the occupant out of hand.

Click to open. (Grand Rapids Press; June 1, 1921)

As the Grand Rapids Press reported on June 1, 1921:

“As dawn broke 60 or 70 motorcars filled with armed men formed a circle completely around the Negro section. Half a dozen airplanes circled overhead. There was much shouting and shooting. A row of houses along the railroad tracks was fired, but lack of wind prevented the flames spreading. A party of white riflemen was reported to be shooting at all Negroes they saw and firing into houses. The Negroes were said to be returning the fire desperately.”

Blacks fought back. A newly consecrated church offered shelter to black riflemen who fired at the mob. The machine gun was brought up and the church shot up. The nearby houses, which had been protected by the men in the church, were then looted and burned. Rather than protect the black citizens, the Tulsa police joined in the riot against them. So did local National Guard troops. Troops from Oklahoma City arrived in early afternoon, but they did not immediately suppress the fighting, though they would by late afternoon. After the fighting died down, whites were allowed to go home. The remaining blacks were rounded up. Eventually hundreds of them were indicted. No white person was. None would be. The original death toll was set at around 90, with a third of them white. That number was revised down to 34, with nine whites and 25 blacks. Later it was rumored that mass graves had been dug in the cemeteries. Ten square blocks of Greenwood had been burned out. The shoeshine boy whose arrest had started these events in motion was never charged.

(Tulsa Daily World; June 2, 1921)

Except for its scale, the Tulsa riot was similar to the race riots that swept the nation in 1919. And when it came time to assess blame, it became the fault of victims.

As the official statement of the mayor put it (published in the Tulsa World on June 14, 1921):

“First, responsibility.

“Let the blame for this negro uprising lie right where it belongs – on those armed negroes and their followers who started this trouble and who instigated it and any persons who seek to put half the blame on the white people are wrong and should be told so in no uncertain language.”

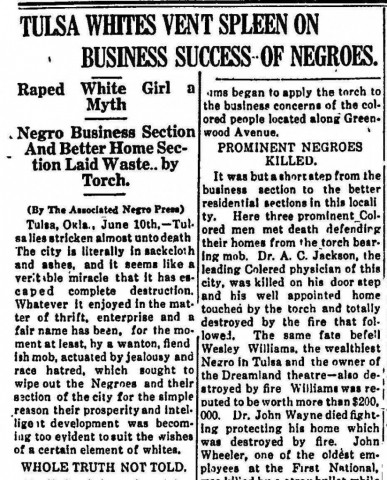

The black press had a different viewpoint:

“Whatever it [the black community] enjoyed in the matter of thrift enterprise and a fair name has been, for the moment at least, destroyed by a wanton, fiendish mob, actuated by jealousy and race hatred, which sought to wipe out the Negroes and their section of the city for the simple reason of their prosperity and intelligent development was becoming too evident to suit the wishes of a certain element of whites”

(Negro Star; June 10, 1921)

What’s truly amazing about the riot is that national memory of it seemingly faded. It wasn’t part of the conversation during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. It was lost in Orwell’s memory hole. It’s understandable that 1920s Tulsa wouldn’t want it brought up as the young city needed outside investment. And the blacks, who rebuilt their community without help from their fellow Tulsans, might have kept quiet as the influence of the Klu Klux Klan grew during the 1920s. Not only did they get no help, but a portion of Greenwood was taken to become a train station. In a newspaper article printed May 31, 1996, Sam Howe Verhovek wrote:

“But as the years and then decades passed, Tulsa seemed determined to forget the riot. No memorial was erected; no citywide commemoration was held; not a single person was ever charged with the deaths or the fires. In the city library, articles about the riot and the formation of white lynch mobs were simply cut out of that day's issue of The Tulsa Tribune.”

Searching in African American Newspapers, 1827-1998, on the ten-year anniversary dates doesn’t yield any articles on the fighting in Tulsa. Searching more broadly from a few years after the riot through 1998, one finds mentions of it in articles, but often they are announcing gains made since the riot, or noting that an individual was a survivor. Only after the 1980s does the riot come up, once in reference to Mayor Wilson Good’s aerial bombing of the MOVE house in Philadelphia. Finally, after the Murrah Federal Office Building bombing in Oklahoma City, the Oklahoma legislature established in 1997 a commission to look into the riot. Tulsa had just held its first commemoration on the 75th anniversary of the event in 1996. The commission published its report before the 80th anniversary in 2001. It can be read in PDF on the website of the Oklahoma Historical Society: http://www.okhistory.org/trrc/freport.htm. The narrative of the events of the riot found in the commission report was written by historian Scott Ellsberg and is well worth reading, providing context and detail. To request trial access to Early American Newspapers, African American Newspapers, or both, please contact readexmarketing@readex.com.