“The illigant position of a man-shaver”: A Look at Three 19th-Century American Farces

The third release of Nineteenth-Century American Drama includes plays that are self-identified as farces or comedietta, a more abstruse variation.

A Little More Cider: A Farce was published in 1870 by George M. Baker. Here are the characters of this work, which is also identified as a temperance play:

Erastus Applejack, the cider-maker.

Zeb Applejack, his son.

Deacon Peachblossom.

Isaac Peachblossom, his son.

Hans Drinker.

Miss Patience Applejack.

Polly Applejack.

Hetty Mason.

Like many such productions, this one is written in a dialect. Unlike many, it is not so easy to identify it. An excerpt:

Zeb. Gosh all hemlock! Polly, what air yeou a thinkin’ on? Thinkin’ ‘bout some feller, I bet.

Polly. Wa’n’t doin’ nothin’ of the sort. I was thinkin’ ‘bout my new Sunday bunnet.

Zeb. Well, fashion or fellers, they’re all alike. When a gal gits thinkin’ ‘bout either on ‘em, she ain’t good for nothin’.

Polly. Precious little you know ‘bout either on ‘em. I heerd Sally Higgins say that your go-to-meetin’ coat looked as though it had been made in the Revolution.

The Applejacks and Peachblossoms are at sixes and sevens because of the production of alcoholic cider. This is further complicated because of the star-crossed lovers in both generations. Hans Drinker, identifiably meant to be German, is introduced to distract from feuding family members.

Hans. Goot tay, mine Friend Applejack: it is varmer dan never vash, and I ish very try. I vould like some trinks.

Applejack. Oh, some of my cider! Hey, Hans?

Hans. Yaw, dat is goot cider. I have never trinks such goot cider sine ven I cooms from Faderland, and dat vash lager bier.

Cider sold in whiskey kegs, whiskey kegs still containing whiskey, intemperate deacons, and sufficient hilarity ensues. The comic drama is a simple diversion, the characters familiar, and the plot improbable.

A Close Shave, also subtitled A Farce, was published in Boston in 1868 by C.H. Spencer. Spencer was Charles H. Spencer, the brother of William V. Spencer who published many plays in Boston in the mid-nineteenth century. His imprimatur was subsequently subsumed by Lee & Shepard of Boston who were the publishers of A Little More Cider, the farce highlighted above. The name C.H. Spencer appeared often as the putative author of many scripts. More likely, he was the publisher rather than the playwright.

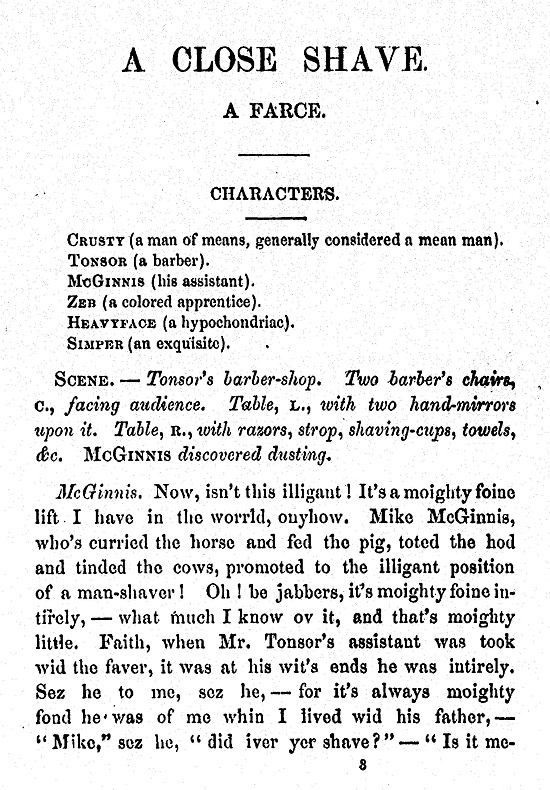

The cast of characters reflects the style of farce bearing in mind the title:

Crusty (a man of means, generally considered a mean man).

Tonsor (a barber).

McGinnis (his assistant).

Zeb (a colored apprentice).

Heavyface (a hypochondriac).

Simper (an exquisite).

Presumably, the dialect is meant to be Irish. Here is McGinnis:

Now, isn’t this illigant! It’s moighty foine lift I have in the worrld, onyhow. Mike McGinnis, who’s curried the horse and fed the pig, toted the hod and tinded the cows, promoted to the illigant position of a man-shaver! Oh! Be jabbers, it’s moighty foine intirely,—what much I know ov it, and that’s moighty little. Faith, when Mr. Tonsor’s assistant was took wid the fever, it was at his wit’s ends he was intirely. Sez he to me, sez he,—for it’s always moighty fond he was of me whin I lived wid his father,—“Mike,” sez he, “did iver yer shave?”—“Is it meself?” says I: “faith, yes,—wid a pair of scissors.” “No, no! sez he “did ever yer shave anybody?” “Faith yes,” sez I—“the pig.”—“Oh, murther!” says he: “I mane a man.”—“Niver a wun,” sez I; “but I could soon learn.” And so he took me in here to learn the business; but it’s precious little I’m learning, for the mashter does all the shaving: but the time must come, and then look out for yourself, Mike McGinnis.

By contrast, Zeb, the “colored apprentice,” demands to know “Who-o-o-‘s a n…er? Who—who’s a n…..? Dar ain’t no n…ers now: didn’t de prancepation krocklemation make ‘em white folks, hey?...a parcel of ignumramuses a-yellin’ and a-shouten’ as ef dey nebber seed a tanned man afore. What does the Declamation of Indempendence say, hey?”

While there are elements of farce, largely entailing courtship, the author seems intent on scraping up stereotypical characters. Witness Simper “an exquisite.”

Simper. Now, weally, ‘tis disgustingly vulgaw,—it is weally,—the ideah of a wefined gentleman being compelled to [entaw?] such a howid place, to have his chin shaved. And his whiskaws twimmed: it is weally!

Mike. Your turn next, sir: take a seat.

Simper. My turn next? Do you weally mean to say that I must wait? Aw!

Mike. Faith, honey, you must: there’s niver a wun to shave you at all, at all!

Simper. But I can’t wait,—I can’t weally. I have a pwessing engagement. A dear, delightful cweecher is fondly waiting my coming,—she is weally.

Simper is seated in Zeb’s chair for his shave. It is the first time Zeb has actually shaved someone. The consequences are not difficult to predict. There are tonsorial mishaps, relationship miscommunications, and dashed hopes to come. Still, the main argument concerns whose turn is next to be shaved in this barber shop from hell.

Crusty. Hold on, Tonsor: there’s something else. Here’s Simper: he’s lost a wife and half his whiskers; I’ve lost a daughter and half mine; so I’ll take the chair.

Heavy. Hold on! hold on! it’s my turn next!

Crusty. Why, you’ve just been railing at barbers and razors and the wickedness of the world: will you put yourself in their hands?

Heavy. To be sure I will. We’re all going to the bad. I’m reconciled, and they can’t hurt me.

Crusty. Well, have your turn; and, after you get through, I’ll see if I can’t have what I came here for.

Ton. What was that, father-in-law?

Crusty. A clean shave.

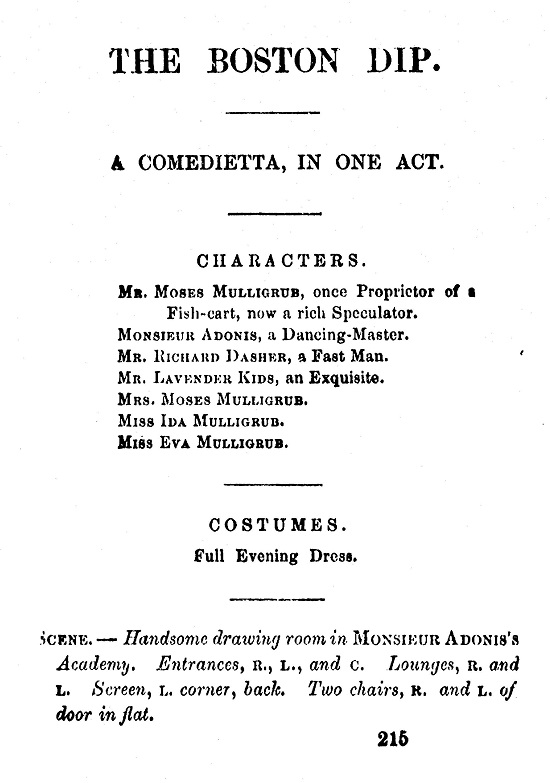

The first two plays presented here identified themselves as farces. Our third, The Boston Dip, identifies itself as a “comedietta”—generally defined as a light farcical comedy of one or two acts. Here are its characters:

Mr. Moses Mulligrub, once Proprietor of a Fish-cart, now a rich Speculator.

Monsieur Adonis, a Dancing-Master.

Mr. Richard Dasher, a Fast Man.

Mr. Lavender Kids, an Exquisite.

Mrs. Moses Mulligrub.

Miss Ida Mulligrub.

Miss Eva Mulligrub.

The setting is a “Handsome drawing room in Monsieur Adonis’s Academy.” The costumes are simply described as Full Evening Dress. It can be argued that this amusement is as dialectical as the previous two imprints. It may simply depend on perspective.

Music, as curtain rises, Straus’s waltz, “Beautiful Blue Danube.” Miss Ida and Miss Eva discovered waltzing, introducing “The Boston Dip.” They waltz a few moments, then stop. Music ceases.

Ida. Now, isn’t that delightful?

Eva. Delightful! It’s positively bewitching. Bless that dear Monsieur Adonis. He deserves a crown of roses for introducing to his assembly the latest Terpsichorean novelty. O, we shall have a splendid time tonight!

Ida. Especially as those charming waltzers, Messrs. Richard Daher and Lavender Kids, “the glass of fashion and mould of form,” are to honor us with their presence.

The sisters tease each other about their interests in the aforesaid gentlemen and argue about their father’s humble beginnings as a fishmonger. Their aspiring mother joins them and disparages her husband’s past. She has engaged the dance-master to teach her the “Boston Dip” in private so that “nobody will know anything about it until I’m deficient.” She proves to be a committed Mrs. Malaprop.

When Kids enters his speech is instantly familiar.

Kids (with glass to his eye). Now, weally! Have I stumbled into the bodwaw of a bevy of enchanting goddesses?—have I, weally?

Eva. You have, weally.

Subsequently:

Kids. I say, Dashaw, I’ve had my bwains surveyed to-day.

Dasher. Have you? I didn’t know you had any.

Kids. Yaas, several. Destwuctiveness, combativeness, idolitwy—

Dasher. Ideality.

Kids. Yaas, it’s vewry wemarkable how those phwenological fellaws lay out your bwains, and name them just like—aw—stweets.

Dasher (aside). They must have labeled some of yours “No Thoroughfare.”

For more information about Nineteenth-Century American Drama, please contact Readex Marketing.