The first Egyptian mummy to be exhibited commercially in America was a stonecutter from Thebes named Padihershef. This ancient gentleman arrived in Boston in early May 1823 and was exhibited up and down the East Coast, visiting twelve different cities in 1823 and 1824. By the end of 1824 several more mummies had arrived, museum proprietors having determined that a mummy was a great money-making attraction, even at the small admission charge of “twenty-five cents; children half-price.”

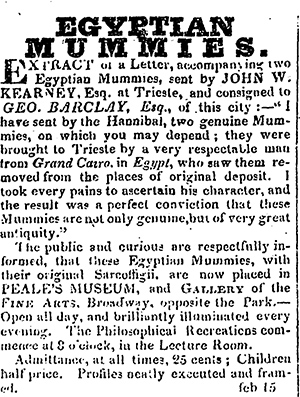

On 15 February 1826 an article appeared in the New York Commercial Advertiser announcing the arrival of two Egyptian mummies, aboard the ship Hannibal, consigned to George Barclay of that city. They had been sent from Trieste by consul John Kearney, and were guaranteed to be genuine. Shortly after their arrival, they were bought by Rubens Peale for his New York Museum for the sum of about $2,000. Although Peale had previously made a profit of almost $750 exhibiting Padihershef for six weeks, his father, Charles Willson Peale, thought he had made a bad bargain, believing these new mummies would not draw enough interest to offset their cost. But Peale needed a spectacular attraction to compete with John Scudder’s American Museum, which had an Egyptian mummy of its own.

Peale had the mummies examined and authenticated by several doctors, and then partly unrolled them before putting them on exhibition at his museum. By April of 1827 he had sold one of the mummies, which was in a curious “blockheaded” coffin (identified as a Roman-style coffin by John Taylor of the British Museum) to Messers Frederick Boughton, Ira Curtis, and Ebenezer G. Holt who began exhibiting the mummy around the Northeast. They began in Ithaca, New York, and thence to Buffalo. By the beginning of 1828 they had concentrated their efforts in Vermont and New Hampshire—at “the house of Mr. Abbott, in East Poultney, Vermont, on Tuesday, the 1st; at Mr. Greeno’s in Fairhaven Wednesday, the 2d; at Mr. Moulton’s in Castleton, on Thursday the 3rd, and at Mr. Gould’s, in Rutland, on Friday, Saturday and Monday, the 4th, 5th, and 7th of January.” Then off to “Mr. Webster’s, in Hartland, on Monday the 11th; Mr. Peite’s, in Windsor, on Tuesday and Wednesday, the 12th and 13th; Mr. Stevens, in Claremont, on Thursday and Friday, the 14th and 15th—and at Mr. Hassma’s in Charleston, on Saturday and Monday, the 16th and 18th of February. Tickets 12 ½ cents (to be had at the bar).” Hours of exhibition were from 9 A.M. until 9 P.M. The exhibition was closed on Sundays, possibly because these locations were taverns, which according to law, were not open on the Sabbath.

In March the mummy and its curious coffin were en route down the Connecticut River Valley. It went first to Mr. Newton’s in Greenfield, then Mr. Gilberts in Deerfield, Field’s tavern in Sunderland, Mr. White’s in Hatfield, Russel’s tavern in Bloody Brook, Mr. Warner’s in Northampton, Mr. Swan’s in Westfield for two days, and ended up in a room over S. Warriner and Son’s store in Springfield at the end of the month. No record has yet been located that traces the mummy’s further adventures until he shows up back in New York state near the end of summer.

On 8 August 1828, underneath a woodcut of the coffin (which had probably been painted in brilliant colors), the Saratoga Sentinel announced the mummy would be on view at Bailey’s Congress Springs Hotel “for a few days only.” The advertisement had been inserted on the fifth of August. Tickets were 12 ½ cents and, as in other venues, could be had at the bar.

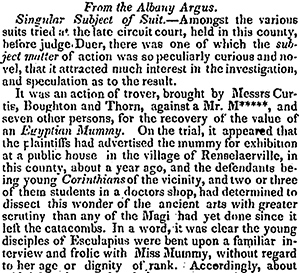

Later in 1828 “Blockhead” (the soubriquet is given by me as the coffin gives no clue as to the occupant’s real name and this describes the shape of the coffin) was exhibited at a public house in Rennselaerville, New York, where its journeys ended. Eight young men, some of them medical students, out of a desire to prove that the mummy was genuine, decided to dissect the mummy. At about midnight they broke into the establishment, subdued the attendant “with no easy hand” and “hurried her mummyship down the stairs with more haste than the gravity of the situation could at all justify.” At this time most Egyptian mummies were referred to as “she,” probably because of the depictions of wigs and jewelry on their coffins. It is particularly amusing in this instance as the coffin appears to show a moustache and beard on the face.

In 1829, Messers. Curtis, Boughton, and Thorn (who had replaced Holt) sued the young gentlemen to recover the monies they would have earned had they been able to continue their exhibition of the mummy. It had been producing a net income of eight dollars a day. The courtroom battle devolved on whether or not the mummy was “property,” and, if so, who owned it? The defense argued the only person who could properly claim the mummy was its last, lineal descendant. Moreover, it could not be considered property as it was a human, having no intrinsic value and thus worth nothing. The prosecution countered that it was as much property as were any physicians’ anatomical specimens. The defense responded that the mummy’s direct descendants would have had to sell the body. The prosecution crowned the argument by pointing out that as the Pasha of Egypt had become the administrator general of all the catacombs in Egypt, where the mummy had been buried and discovered, he was therefore quite legally within his rights to sell off the contents.

Judge Duer and the jury returned a verdict for the plaintiffs, in the amount of $1,200, plus legal costs of the suit.

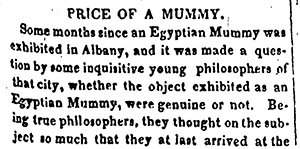

The story was picked up and repeated in various forms in newspapers all over the Northeast where the question was asked, “What is the price of a mummy?”

“Blockhead” was certainly the most peripatetic of the mummies imported into the Early Republic. This can be clearly seen from the scattered newspaper references that have been located. As Readex continues to scan and digitize more newspapers from the time period, it is to be hoped additional information can be gleaned about this curious mummy and his travels.