When researching a topic such as the history of eighteenth-century hymnbooks, databases such as America’s Historical Imprints can greatly enhance access to rare materials, but I recently found that research questions also lurk in the digital archive. Out of curiosity, I did a search for materials listing Isaac Watts (the century’s most popular hymn writer, starting in 1707) as an author in Early American Imprints, Series I: Evans, 1639-1800, to see how early an American edition of Watts would be available in images. The literature on American hymnody had led me to expect one or two printings in the 1720s, a few more in the 1730s, and an explosion in the 1740s in the wake of the Great Awakening. My search, however, returned hits going back into the 1710s—with Cotton Mather listed as the author! I was prepared for the bibliographies to miss a few titles, but how could the database think that Mather had written Watts’s hymns? By the time I had answered this question, I was well on my way to an article.[i]

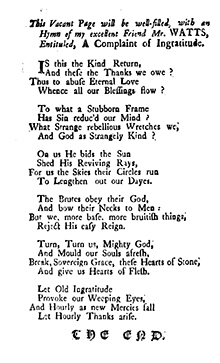

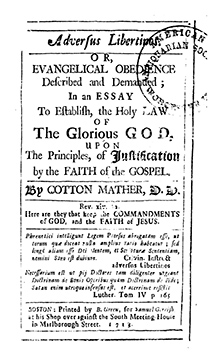

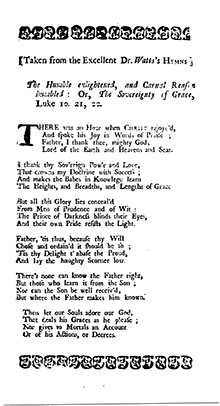

As it turns out, Mather didn’t write the hymns. What he wrote were sermons, which he and his supporters published by the hundreds alongside commentaries, devotional and pedagogical works, as well as the Magnalia Christi Americana—which isn’t in Early American Imprints since it was published in London and reprinted in the US only after the 1819 cutoff of Series II: Shaw-Shoemaker. The hits from my Isaac Watts search were Mather’s sermon pamphlets, each of which included one or more Watts hymns at the end, under a heading which read something like, “Let a Hymn of the admirable Dr. Watts fill this Vacant Page.” There were over half a dozen of these published sermons with hymnic afterthoughts, which of course turned out to be much more deliberately placed than the prefatory statements suggested: each hymn was on the same topic or biblical passage as the sermon it followed, indicating that Mather intended some reinforcement of his pastoral message through the poetry of his friend and correspondent.

It also turned out this wasn’t a new discovery. Hymnologist David W. Music mentions six of these sermon pamphlets in a 1999 essay [ii] that presented research done with the Early American Imprints microfilm. I learned of Music’s work after my initial findings, and I soon realized that the search capabilities of the database would allow me to expand the list of known sermon-hymn pairings. Using a series of searches—“Mather” as author, “Watts” in citation; “Mather” as author, “Watts” in full text; “Mather” as author, “hymn?” in citation (and again as full text); “Watts” as author, “hymn?” in full text—I found that Mather used Watts texts in twelve sermons between 1712 and 1715. I also learned that Mather had earlier used his own hymns anonymously in a similar way, certainly by 1696 and possibly as early as 1693; a brief cross-reference in the database Literature Online confirmed Mather’s authorship of those earlier hymns, as well as in which of Watts’s collections the selected hymns appeared. Mather drew both from the 1709 Hymns that he had received as a gift from Watts in 1711, as well as from Horae Lyricae, Watts’s earlier collection that was not intended for liturgical use but included many poems in standard hymn meters.

But what did all this mean? A little research into the liturgical practices of Mather’s time showed that Calvinist churches in New England (and elsewhere) followed Calvin’s teaching that congregational song was an important part of worship, but the only acceptable texts were those from the Bible: the Psalms, plus a few additional songs from Revelation and other parts of Scripture. Mather was an avid composer of hymns and reader and singer of them in his private and family devotions, but even during controversies over congregational singing in the 1720s, he never questioned Calvin’s ban on hymns in church. To include hymns, whether his own or Watts’s, at the end of a printed sermon signaled that the sermon had been somehow removed from its original context, transplanted from a liturgical to a devotional context that allowed for more meaningful blends of prose and poetry. (Not only were the Calvinists of Mather’s time limited to the Psalms, but they also sang them “in course,” in order from Psalm 1 to 150, likely an annoyance to a linguistically sensitive preacher who routinely exegeted passages that had nothing to do with a given service’s psalm texts.) My findings in the Early American Imprints database showed that Mather took an interest in creating devotional moments out of sermon-hymn pairings across several decades of his career, and when he told Watts in a 1715 letter that he had been spreading his hymns across the land, he clearly had his sermons in mind as a form of distribution and advertising.

Watts’s hymns would eventually catch on in American worship services, starting in the 1730s as the Great Awakening swept the Atlantic seaboard. My searches that focused on Watts rather than Mather as an author further revealed that over half a dozen more New England preachers followed Mather’s lead in including Watts in their printed sermons, the most notable being Jonathan Edwards’ 1734 printing of A Divine and Supernatural Light, which Edwards published as a memorial to his congregation of the religious fervor they were experiencing at the time Edwards preached that sermon. The sermon-hymn pairings continued into the 1760s, both with Watts and, in the case of Mather’s nephew Mather Byles, verses written by the preachers themselves. By this point, hymns were becoming an accepted part of Protestant worship, especially outside of the cities and among Methodists, Baptists, and revivalistic Presbyterian New Lights. But what I have been able to learn from Early American Imprints is that American hymnody has an earlier history of treating hymns as read texts, meant for devotion and joined to the homiletic tradition of Puritan sermon-pamphlets, a history all but invisible without creating such a constellation of texts.

Footnotes:

[i] Christopher N. Phillips, “Cotton Mather Brings Isaac Watts’s Hymns to America; or, How to Perform a Hymn Without Singing It,” New England Quarterly 85.2 (June 2012): 203-221.

[ii] David W. Music, “Isaac Watts in America Before 1729,” Hymn 50.1 (Jan. 1999): 29-33.