In summer 2015, a wooden frigate named the Hermione sailed from France to the United States. It was recreating one of the voyages that brought the Marquis de Lafayette to fight in the American War of Independence. The new Hermione was a painstaking replica of Lafayette’s ship, built with authentic eighteenth-century methods. Its voyage, however, became a modern multimedia spectacle—with international television coverage, a website, and a busy Twitter account.

Advanced technology aside, something similar happened nearly two hundred years ago. In the summer of 1824, Lafayette himself, now an elderly man, returned to the United States after many years in France. Enormous crowds of Americans, many of whom were too young to remember the Revolution at all, turned out to see the legendary general in person. His tour of U.S. cities also became a national journalistic event; today, we can trace it through thousands of surviving newspaper articles. Exchanging stories through the federal postal system, newspaper editors helped their readers visualize other communities’ celebrations. By doing so, they helped Americans experience the feeling of membership in one nation.

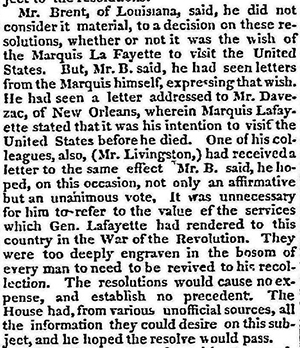

The attention started even before Lafayette sailed from France, and from the start, making sense of a slow and unpredictable information supply was part of the newspapers’ job. For example, in January 1824, when Congress debated a resolution inviting General Lafayette to visit the United States, representatives argued over whether anyone knew for sure that Lafayette would actually want to visit. Congressmen from French-speaking Louisiana claimed to have special information no one else had: they said they had seen letters about the subject from the general himself. Newspapers relayed their information around the country.[1]

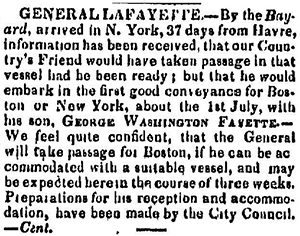

The unpredictability continued long after Lafayette accepted Congress’s invitation. Newspapers tracked his movements as well as they could, trying to help their readers prepare. In June 1824, the New York Gazette announced that the general was finally on his way to New York City from the northern French port of Le Havre. Newspapers in New England picked up the story, but they seemed mildly skeptical—probably in part because they hoped the general would honor Boston with his first American stop instead.[2]

In any case, the story turned out to be premature. [3]

Conflicting reports printed in late July and early August said he would be traveling on the Stephania or on the German ship Brandt.[4]

By the middle of August, when readers in Boston learned (correctly) that Lafayette had embarked for New York on the Cadmus, the Boston Commercial Gazette was already eager to “have the hurly-burly over.”[5]

Most newspapers, however, did their best to build up the excitement ahead of Lafayette’s arrival. The Saratoga Sentinel would “make no apology for occupying so large a portion of our paper” with Lafayette; he was the only person still alive “whose services could call forth such general expressions of gratitude.” A Philadelphia newspaper (echoed by one in Bridgeport, Connecticut) observed that this voyage was now “the one great object of national feeling” and encouraged readers to make sure it would be “celebrated with a pomp and demonstration of feeling, wholly unknown in this, and perhaps in any other country.”[6]

Because Lafayette’s tour was to include multiple stops around the Union, it could help knit together scattered American communities. Even though it would take months for Lafayette to complete his tour—and even though it might take weeks for news to spread from town to town—the newspapers imagined his arrival as a moment of simultaneous joy. Some newspapers reprinted a suggestion from Baltimore: when people received word that Lafayette had landed somewhere on American shores, their towns (“from Maine to Louisiana”) should each fire “a Federal Salute” of guns or artillery to mark the beginning of “the general rejoicing in this Country.”[7]

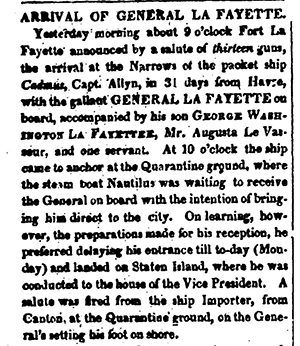

At long last, General Lafayette arrived in New York harbor on the morning of Aug. 15, 1824. Over the next two weeks, detailed accounts of his lavish welcome in Manhattan spread slowly to other towns, which set up committees to arrange their own receptions and celebrations.[8]

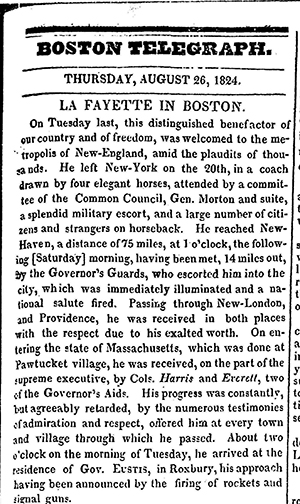

Later that month, Lafayette left New York to begin a long overland tour that would eventually take him to Boston, Providence, Albany, Rochester, Baltimore, Williamsburg, Philadelphia, Washington, and many towns in between. It was not until September 1825, more than a year later, that he would board the U.S. warship Brandywine in the Potomac River to sail back to France. At almost every stop, accounts of his arrival were published in local newspapers, and these articles were often reprinted by newspapers hundreds of miles away.[9]

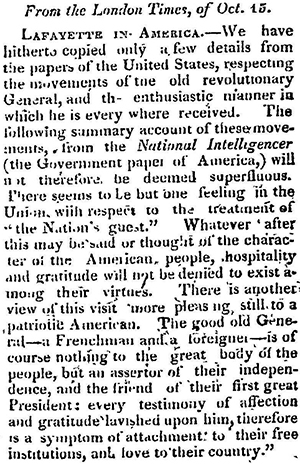

Consistently, these stories emphasized the intense emotion Lafayette inspired in the people who came out to see him. Some of these articles even made their way across the ocean to be collected by curious Europeans. The London Times observed that there seemed to be “but one feeling in the Union.”

In France, on the other hand, a newspaper edited by Lafayette’s political enemies warned this unity was dangerous. The United States and its journalists, it said, aimed to raise “a strong mass of republican states” against the monarchs of Europe and ultimately to spread democracy across the rest of the New World. For this newspaper, Lafayette was a symbol and a carrier of radical American ideas. Both of these articles made their way back across the Atlantic to be reprinted by newspapers in the American south.[10]

Such unity was remarkable in a country comprising so many different kinds of communities. It was also deceptive. Lafayette was touring the United States just as the presidential election of 1824 demonstrated that the country had deep and painful political divisions. These divisions would intensify in the years to come. As a living link to the republic’s revolutionary past, the old French general was temporarily bringing together a country that some people worried might be falling apart. Perhaps this turmoil, paradoxically, was why so many Americans opened newspapers that year hoping to learn about his journey. It is also the reason we can know so much today about that journey and the feelings it inspired.

Footnotes:

[1] “House of Representatives,” Baltimore Patriot (Jan. 15, 1824), 2; “Marquis Lafayette,” Alexandria Gazette (Jan. 17, 1824), 2; “First Session, Eighteenth Congress: Senate,” Massachusetts Spy (Jan. 21, 1824), 2-3; and “Marquis Lafayette,” Trenton Federalist (Jan. 26, 1824), 2.

[2] “General Lafayette,” Boston Commercial Gazette (June 14, 1824), 2; “General Lafayette,” Concord Gazette and Middlesex Yeoman (June 19, 1824), 3; “General Lafayette,” American Advocate & General Advertiser (June 19, 1824), 3; “General Lafayette,” National Aegis (June 23, 1824), 3; and “General Lafayette,” Bangor Register (June 24, 1824), 3.

[3] “General Lafayette,” New-Bedford Mercury (July 16, 1824), 3; “General Lafayette,” Rhode-Island American (July 16, 1824), 2; “General Lafayette,” Farmer’s Cabinet (July 17, 1824), 3; and “General Lafayette,” Boston Commercial Gazette (July 19, 1824), 2.

[4] “[A letter from Havre],” Daily National Intelligencer (July 29, 1824), 3; “[A letter from Paris],” Rhode-Island American (July 30, 1824), 2; “La Fayette,” Connecticut Mirror (Aug. 2, 1824), 3; “[A letter from Paris],” Connecticut Gazette (Aug. 4, 1824), 3; and “Lafayette,” Hallowell Gazette (Aug. 4, 1824), 2.

[5] “General Lafayette,” Boston Commercial Gazette (Aug. 16, 1824), 2.

[6] “Gen. La Fayette,” Saratoga Sentinel (Aug. 25, 1824), 3; and an article in the United States Gazette, reprinted as “La Fayette,” Connecticut Courier (Aug. 25, 1824), 2.

[7] “[A Baltimore paper suggests],” American Sentinel (July 28, 1824), 3; “[A Baltimore paper suggests],” American Advocate (July 31, 1824), 3; and “Gen. La Fayette,” Hampshire Gazette (Aug. 4, 1824), 3.

[8] “Arrival of General La Fayette,” New York Evening Post (Aug. 16, 1824), 2; “Landing of La Fayette,” National Advocate (Aug. 17, 1824), 2; “Arrival of Gen. La Fayette,” Woodstock Observer (Aug. 24, 1824), 2; “Landing of La Fayette,” Richmond Enquirer (Aug. 24, 1824), 2; “Arrival of Gen. La Fayette,” Charleston Courier (Aug. 25, 1824), 2; “Arrival of La Fayette,” Savannah Georgian (Aug. 26, 1824), 2; and “Landing of La Fayette,” Washington [Pa.] Reporter (Aug. 30, 1824), 2.

[9] “La Fayette in Boston,” Boston Telegraph (Aug. 26, 1824), 3; “Gen. La Fayette,” New Bedford Mercury (Aug. 27, 1824), 3; “Progress of La Fayette,” New York Spectator (Aug. 31, 1824), 1; “Progress of La Fayette (From the Providence Patriot),” Connecticut Herald (Aug. 31, 1824), 2; “Lafayette’s Tour,” Concord Gazette and Middlesex Yeoman (Sept. 11, 1824), 2-3; “Journey of La Fayette to the North,” New York Statesman (Sept. 21, 1824), 2-3; “Lafayette’s Reception in Baltimore,” Boston Commercial Gazette (Oct. 14, 1824), 1; “Gen. La Fayette’s Reception at Williamsburg,” Richmond Enquirer (Nov. 5, 1824), 4; “Reception of Gen. La Fayette in Vermont,” Danville North Star (July 12, 1825), 1-2; “La Fayette in Philadelphia: From the Aurora,” Alexandria Gazette (July 21, 1825), 2; “La Fayette at Rochester,” New York Statesman (July 29, 1825), 4; “[General La Fayette has once again visited our city],” Washington Daily National Journal (Aug. 15, 1825), 2; “Trip to the Brandywine,” Washington Daily National Journal (Sept. 10, 1825), 4; and “La Fayette at Sea,” Saratoga Sentinel (Sept. 20, 1825), 3—among many others.

[10] “From the London Times, of Oct. 15: Lafayette in America,” Fincastle Mirror (Dec. 31, 1824), 3; and “Lafayette in America,” Savannah Georgian (Jan. 4, 1825), 2.

Additional Reading:

Lafayette’s Hermione Voyage 2015. http://www.hermione2015.com

Laura Auricchio, The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014)

Stanley J. Idzerda, Anne C. Loveland, and Marc H. Miller, eds., Lafayette, Hero of Two Worlds: The Art and Pageantry of His Farewell Tour of America, 1824-1825 (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1989)

Harlow Giles Unger, Lafayette (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2002)

Sarah Vowell, Lafayette in the Somewhat United States (New York: Penguin Random House, 2015)