Readers of the Washington, D.C. newspaper The Daily National Intelligencer witnessed a strange and disturbing transformation in 1847, when the nation’s most popular literary character freely admitted that he had become a greedy, cynical killer. Soon enough this beloved American hero, whose name was synonymous with Yankee Doodle, would threaten to stage a military coup to seize the Capitol and overthrow Congress! Readers of the Early American Newspapers archive can follow along, gleaning important hints to decoding contemporary political rhetoric.

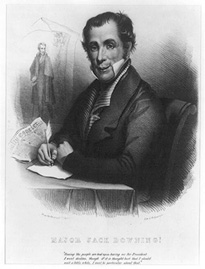

(Portrait credit: Library of Congress Prints

and Photographs Division)

The Intelligencer, formerly a nonpartisan legislative record, became the flagship of the Whig Party when it split from Andrew Jackson’s Democrats in the early 1830s. But it was during the second year of the war between the United States and Mexico that the newspaper would green-light one of the most audacious political satires in U.S. history. If you imagine a sequel to Forrest Gump in which the benign protagonist masterminds the torture of the Abu Ghraib detainees, you might gather some sense of the controversy produced by the corruption of Seba Smith’s iconic everyman, Major Jack Downing.

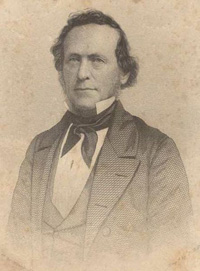

American humorist and writer.

Smith created Jack in 1830 while editing the Portland Courier. An ambitious but naïve young man who abandons his family farm in rural Maine to seek his fortune in the state capital, Downing represents the humorous aspect of what Ralph Waldo Emerson would call American “self-reliance.” In an era of opportunity characterized by rapid economic expansion and the birth of the modern partisan political system, Jack’s letters from Portland to his relatives in “Downingville” echoed the fears of Courier readers that urbanization would destroy the national character. But they also softened this sudden and wrenching cultural shift by phrasing it in a semiliterate homespun vocabulary larded with quaint barnyard metaphors.

When newspapers across the U.S. began reprinting the Downing letters as a sweetener for their editorial pages, Smith responded by expanding his picaresque to a national scale. Thus Jack met President Jackson, who gave him an officer’s commission and dispatched him to settle political disputes with Canada and South Carolina. Like Gump, Downing now found himself amid a swirl of great, consequential events that were beyond his limited understanding. His move to “Washington City” to become an unofficial member of Old Hickory’s cabinet mirrored Smith’s own move to the capital to be a national political correspondent. Smith’s Whiggish conservatism made him skeptical of the entrepreneurial spirit embodied by Jackson. But his swipes at Jackson were voiced by the amiable Jack, the President’s apologist and alter ego, so their tone remained mild. Meanwhile Smith continued to gain readers of all political stripes; many newspapers facetiously campaigned Downing for President, reasoning that he would be a more popular successor to Jackson than Martin Van Buren, Daniel Webster, or Henry Clay.

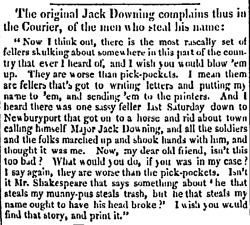

Soon after publishing a collected volume of the Downing letters in 1834,i Smith abandoned the character to pursue new projects.ii But by this point, Major Jack Downing was too ubiquitous to be silenced. Smith’s rural dialect humor had spawned many imitations. Thomas Chandler Halliburton created “Sam Slick” for the Halifax Novascotian, while Augustus Baldwin Longstreet repackaged the Downing style for a Southern idiom and political viewpoint in the Augusta States’ Rights Sentinel. Downing also appeared in numerous political cartoons, where he merged with Yankee Doodle, “Brother Jonathan,” and related comic characters to become the visual archetype of the United States itself, a kind of national mascot. In the absence of enforceable copyright legislation, many Smith disciples simply wrote their own letters under the pseudonym Jack Downing, as Charles Augustus Davis did for the New York Daily Advertiser. The original Downing complained that such impostors were “a rascally set of fellers skulking about who ur worse than pickpockets.” iii

Washington, D.C.; July 6, 1833.

The Major was no longer the exclusive possession of Seba Smith, but instead a true folk hero, a canvas onto which competing visions of American nationalism could be projected. So when Smith penned a new and decidedly more vicious series of Downing letters for the Daily National Intelligencer in 1847, many Americans assumed they were the work of yet another impostor.

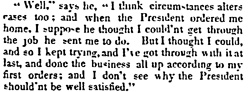

Would Jack Downing, now stationed with Winfield Scott’s army in Mexico City, concede that the purpose of the war was not to avenge unprovoked and unforgivable offenses to American national honor, but to “kill a Mexican, or drive him off from his farm”?iv Would he translate, in his yokel’s slang, the famous sophism of Mexican general Antonio López de Santa Anna, that international treaties were void because “circumstances alters cases”?v

Washington, D.C.; March 6, 1848

Would he tease his compatriots that they were “too skittish” about “digging into the vital parts” of neighboring countries?vi Would he dream of conquering not only the whole of Mexico down to the isthmus of Panama, but the entire hemisphere “clear to Cape Horn,” and then the entire world?vii Would he advise Democratic President James Polk to raze the Washington monument and declare a military dictatorship?viii Thomas Ritchie, editor of the Intelligencer’s Democratic nemesis The Union, thought not.ix Notice the telling misidentification of Smith that doubles the unintentional irony.

We enjoy wit, and have no objection to waggery. We can excuse it, even when the joke is made at our own expense. But then we have a right to ask if the wit be ‘good,’ and the waggery ‘genuine?’… If there was any very extraordinary humor in the letters of this fictitious ‘Jack Downing’ – if there was any of the wit and naïveté of the original Jack Downing – the worthy C. A. D., of New York, the one who universally passes as the author of the Downing Letters – we should give him the credit he deserves… [But] we happen to know that the present Jack Downing, who has written three letters in a mask for the National Intelligencer, is not the Simon Pure, but a counterfeit presentment – in other words, something of the literary ‘jackdaw in the peacock's plumes.’ We fear that our friends of the National Intelligencer knew that they were palming off this amusing trick upon their readers... We undertake to say positively that these letters in the Intelligencer are something of humbugs; that they are not written by the original Jack Downing, of New York; that he has not employed that signature since the days of Old Hickory; and that he would be the last man to satirize [Polk] or his administration.

With the later Downing letters, Smith joins a fraternity of U.S. anti-war satirists that dates to the earliest years of the nation’s existence, and eventually boasts Mark Twain, William Dean Howells, Joseph Heller, and Kurt Vonnegut. If you’ve watched Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert in recent years, or read The Onion, the affinity to their comments on Iraq is unmistakable. Smith decries Polk as an American Caesar, a threat to the republic who has crossed the Rubicon by crossing the Rio Grande, dragging the nation into a war of choice that betrays suspiciously pecuniary motives. He attempts to reclaim his rural everyman from more hawkish appropriators like C.M. Haile, who wrote the lighthearted Mexican War adventures of “Pardon Jones” for the New Orleans Picayune. x

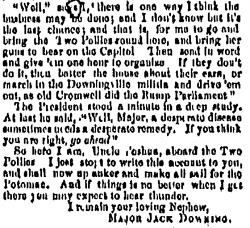

Smith’s Downing letters in the Intelligencer become even more apocalyptic after the war. Rendered despondent when Smith’s Whigs succeed in electing General Zachary Taylor to replace Polk in 1848, Jack regains his swagger in 1852 when Democrat Franklin Pierce defeats General Scott.xi But Downing soon chafes at Pierce’s “backin’ and fillin’ and wrigglin’” hesitation to conquer a long list of territories including Cuba, Hawaii, and French Polynesia, and at Pierce’s failure to pacify domestic hotspots like “Bleeding” Kansas and Mormon Utah.xii So the Major asserts his ‘self-reliance,’ appointing himself commodore of his own fleet of naval mercenaries. After a failed attempt to conquer Cuba, he pilots his flagship into the Potomac and levels his guns at the Capitol, vowing to destroy Pierce’s political enemies.xiii Yankee Doodle has declared war on the United States.

From the Portsmouth Journal of Literature and Politics; New Hampshire; February 2, 1856

The unsettling climax of the Downing saga anticipates two later scenes of classic satire that raise similar questions about American innocence: Twain’s Connecticut Yankee electrocuting 25,000 Arthurian knights and mowing them down with a Gatling gun, and the Slim Pickens character riding the arrow of nuclear armageddon like a bucking bronco in Stanley Kubrick and Terry Southern’s Dr. Strangelove.

Footnotes:

i The Life and Writings of Major Jack Downing, of Downingville, Away Down East in the State of Maine (Boston: Lilly, Wait, Colman, & Holden, 1834).

ii Jack appeared sporadically in the Courier in 1835. In 1836 Smith’s newspaper announced solemnly that he had died from consumption. On moving to New York in the early 1840s, Smith briefly revived the Downing epistolary as a vehicle for some mediocre society humor centered on Jack’s fussy Aunt Keziah. Downing would later claim, in Smith’s 1859 collection My Thirty Years Out of the Senate, that he had published a complete series of letters in the hiatus from 1836-46, but lost them in a fire. See Senate: 246-47 (New York: Oaksmith).

iii From Portland Courier, reprinted in Daily National Intelligencer July 6, 1833 with small editorial changes. Another set of impostor Downings would appear during the Civil War.

iv Daily National Intelligencer December 6, 1847.

v Daily National Intelligencer March 6, 1848.

vi Daily National Intelligencer January 25, 1848.

vii Jack advises Polk to complete his conquest of the Americas before “trying his hand at it over in Europe and Africa,” because “it isn’t well for a body to have too much business on his hands at once.” Daily National Intelligencer October 29, 1847.

viii Daily National Intelligencer January 25, 1848.

ix Senate: 268.

x See C. M. Haile's "Pardon Jones" Letters: Old Southwest Humor from Antebellum Louisiana, ed. Edward Piacentino (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2009).

xi For a more detailed discussion of the 1850s Downing, see John Schroeder, “Major Jack Downing and American Expansionism, 1847-56” New England Quarterly 50.2 (June 1977): 214-33.

xii Daily National Intelligencer Sep. 25, 1855.

xiii Daily National Intelligencer, reprinted in Portsmouth Journal of Literature & Politics February 2, 1856.