What connects the 1849 execution of an obscure African American sailor with Billy Budd, Sailor, the enigmatic novella written by Herman Melville, one of the greatest American writers of the nineteenth century? Perhaps a great deal. Let’s begin with the sailor, a man by the name of Washington Goode, about whom little is known. As a very young man Goode served under Andrew Jackson during the Seminole War, and after the war, he served as a ship’s cook. By 1848 Goode was a resident of “The Black Sea,” a neighborhood frequented by sailors on leave, immigrants, and African Americans, and notorious as a hotbed of vice and violence. 1

On the fateful night of June 28, 1848, Goode was seen attacking his paramour Mary Anne Williams over her involvement with another man by the name of Thomas Harding. 2

Another Murder in Boston. A case of murder, by some secret assassin, who dealt his deadly blows and then fled, occurred in Richmond street in Boston, last night. The man killed was named Thomas Harden, colored, a young man and steward of a vessel. At about eleven o’clock, Harden called at a house in Richmond street, just below Ann street to enquire for a shipmate. Upon being told he was not there, he turned to go out, and had put one foot upon the street steps, when he received two stabs from some unknown hand, one of which was over the left eye, and was an inch and a half in depth; the other was in the back near the spine. Harden fell back into the entry, saying that he was murdered, and died almost immediately. A negro named Washington Goode has been arrested on suspicion of being the murderer. Goode and Harden had had some trouble about a girl, the former being jealous of the latter. It is said that Goode had threatened to take Harden’s life.

When Harding was found dead, Goode was the most obvious suspect. Despite these facts, certain discrepancies raised questions about Goode’s guilt. One of the witnesses had poor eyesight and could not confidently identify Goode as the culprit. Even more damning was the fact that the murder weapon did not match the knife he was known to have had on his person. Nevertheless, the jury delivered a verdict of guilty in under an hour, and he was sentenced to hang. Despite a very public outcry and the support of many abolitionists, Goode was executed on May 25, 1849, protesting his innocence to the very end.

The history of capital punishment in antebellum Massachusetts can best be understood in the context of both this case and a previous case in 1845 in which a jury acquitted Albert Terrill of a capital case due to a dubious argument by defense attorney Rufus Choate that he suffered from somnambulism. It was not so much that the jury believed this as a credible defense. It was that Choate used the argument to mount an impassioned diatribe against the morality of the death penalty. 3

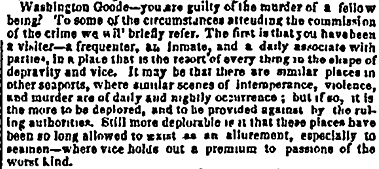

Lemuel Shaw, Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and one of the most important jurists in nineteenth-century America, was presiding judge in both the aforementioned earlier case and the trial of Washington Goode. He was also Melville’s father-in-law. After what was later perceived to be an egregious miscarriage of justice in the name of anti-capital punishment activism, Shaw appeared to believe he could afford to give no quarter with Goode. As such, the prosecution may have been able to make much of the dubious and circumstantial evidence. Goode’s race and the fact that he was a sailor were against him. The “zero tolerance” rhetoric that laces Shaw’s words when he delivered the verdict is illustrative of how little this had to with the murder and how much it had to do with Goode’s questionable “character.”

Washington Goode—you are guilty of the murder of a fellow being? To some of the circumstances attending the commission of the crime we will briefly refer. The first is that you have been a visiter [sic]—a frequenter, an inmate, and a daily associate with parties, in a place that is the resort of every thing in the shape of depravity and vice. It may be that there are similar places in other seaports, where similar scenes of intemperance, violence, and murder are of daily and nightly occurrence; but if so, it is the more to be deplored, and to be provided against by the ruling authorities. Still more deplorable is that these places have been so long allowed to exist as an allurement, especially to seamen—where vice holds out a premium to passions of the worst kind.

While Shaw’s words do not mention race explicitly, abolitionist defenders were quick to seize on Goode’s race as a deciding factor in determining his fate. Consequentially, their defenses often took the tone of blaming his “degraded condition” for his crime, even as they also acknowledged the likelihood that he was indeed innocent. What seems clear is that Goode’s race provided abolitionists an opportunity to lament the racism that might have lead to Goode’s actions. This piece from The Liberator illustrates how abolitionists were often guilty of dwelling on Goode’s character albeit in defense of a commutation.

SHALL HE BE HUNG? In Boston jail lies a colored man, a sailor, named Washington Goode, under the sentence of death. The day of execution is fixed for the 25th of May next.

Some, well acquainted with the facts of the case, entertain the most serious doubts of this guilt; while constantly and most confidentially, he affirms his entire innocence. The verdict rests on circumstantial evidence of the most flimsy character, and the source from which most even of this comes, is most suspicious—men and women of more than doubtful reputation. The main point of the case seemed to be, whether Goode really was the individual seen, at midnight, of a dark and rainy night, by persons on the other side of the street from the individual they declare to be him….Further—this man is friendless, ignorant and neglected; and there are those who fear that a desire to see whether, after the repeated commutations of punishment, the penalty of death can be inflicted in Massachusetts—a desire to test the question, or, in language sometimes heard, “This man shall be hung, or the law formally repealed, has had some weight in dooming this friendless wanderer on the face of society, to the gallows….

This rhetoric reveals the opportunistic nature of some of Goode’s defenders. That he might be innocent made the conviction all the more unjust, but even if he was guilty, he could still be symbolically useful.

For himself, Goode insisted almost to the moment of his death that he was innocent. The night before his execution he attempted suicide through asphyxiation. 4 Goode’s voice is curiously absent from most of the archival materials. He never testified on his own behalf. Upon mounting the gallows steps, he intoned “Lord receive my soul,” before falling “insensible.”

The absence of Goode’s voice emphasizes the skewed nature of the court’s processes by which “innocent until proven guilty” is superseded by the dual bias against both sailors and people of color. In this way, one might read Billy Budd’s fatal flaw, his stutter, as Melville’s way of highlighting the role of voice and voicelessness in the judicial system. The white Billy Budd’s inability to speak echoes the black Washington Goode’s silence.

One might consider the choice of making the character of Billy Budd white as a way to demonstrate both the failures of the justice system to apply the law equitably in regards to race and the manner in which crime, particularly violent crime, racializes suspects. On April 5, 1875, approximately around the time that Melville might have begun work on Billy Budd Sailor, a fourteen-year-old youth called Jesse Pomeroy was tried and convicted in Massachusetts of the murder of several younger children. Unlike Goode, although Pomeroy was sentenced to death, he was never executed due to the governor’s refusal to sign the death warrant. Pomeroy’s brutal crimes were shocking, but his youth plus the lingering bad feeling over Goode’s execution, and its effect on subsequent murder cases, put the question of whether he should be executed in doubt. A notice in the Salem Register outlines these concerns.

The murder of Mrs. Bingham may have much influence in deciding the fate of Pomeroy. Many are of opinion that Webster never would have gone to the gallows, if Washington Goode, the poor colored sailor who while drunk had caused the death of a fellow being, had not so recently been hanged; so the murderer of Parkman could not consistently be pardoned, or have his sentence commuted. We hope something will be done in Pomeroy’s case, to relieve the community of the feeling of insecurity his liberty would create.

The governor eventually commuted Pomeroy’s sentence to life imprisonment. He died in 1932 at the Bridgewater Hospital for the Criminally Insane.

In Herman Melville’s final novella Billy Budd, Sailor, Melville introduces us to the character of Billy Budd by having his narrator first recall the sighting of an anonymous black sailor in Liverpool. The strategy is an interesting one as it seems to suggest that the story is going to engage with race in some substantial way, but instead, the sailor disappears and instead we are treated to a story about a white sailor, Billy Budd, who upon being impressed into service for the British Navy finds himself the target of the jealous master-at-arms Claggart. When Claggart’s attempt to frame Billy for mutiny goes awry, and Billy kills him in a moment of panic, Billy finds himself condemned to hang at the urging of the ship’s captain, Captain Vere. 5

It may at first glance seem counterintuitive to claim that Washington Goode—who was black—could have inspired the character of Billy Budd—who was described as having “Anglo Saxon” good looks. However, the specifics of the Goode case offer tantalizing echoes of the fictionalized Budd trial. And while scholarship has often pointed to Melville’s father-in-law Massachusetts Chief Shaw as inspiration for the character of Captain Vere, the Washington Goode case has been largely overlooked. What comes into focus when viewing the evidence against the posthumously published novella is a study in carefully constructed opposites. In standing in for the black, despised, and probably innocent Goode, the white, beloved, and definitely guilty Budd highlights the fault lines surrounding justice and race by showing the precarity of privilege in a world bent on making examples out of individuals in the name of institutional integrity.

Footnotes:

1 Wilhelm, Robert, Wicked Victorian Boston, (Charleston: History Press, 2017) 20-27.

2 The article misspells Harding as Harden.

3 Rogers, Alan, “‘Under Sentence of Death’: The Movement to Abolish Capital Punishment in Massachusetts, 1835-1849” The New England Quarterly Vol. 66, No. 1 (Mar., 1993), pp. 27-46. Terrill would be tried again two years later for arson and again acquitted.

4 Rogers. Massachusetts and the Death Penalty, (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2008). 9.

5 Melville, Herman. “Billy Budd Sailor,” Melville’s Short Novels. ed. Dan McCall. (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2001).