'Free Talk About Free Books': Tracing the evolution of America’s libraries through primary source documents

1. From private collections to public repositories

The first libraries in the United States were largely private, the realm of wealthy and learned men. During the Colonial Era, these men bequeathed books to educational institutions, establishing early college libraries. They also initiated subscription libraries, which were private collections funded by memberships and dues. While such institutions weren’t available to the general public, they laid the foundation for the public lending libraries that soon became a hallmark of American civic and intellectual life.

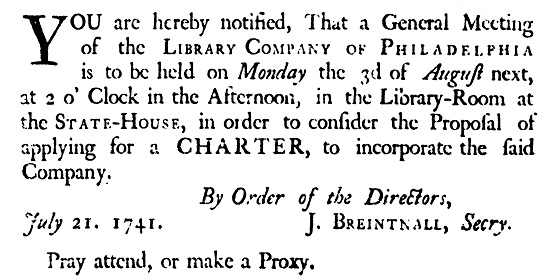

One of the earlier imprints chronicling this evolution is a broadside dated 1741, found in Readex’s Early American Imprints, notifying the public of a meeting “in order to consider the Proposal of applying for a CHARTER, to incorporate the said Company.”

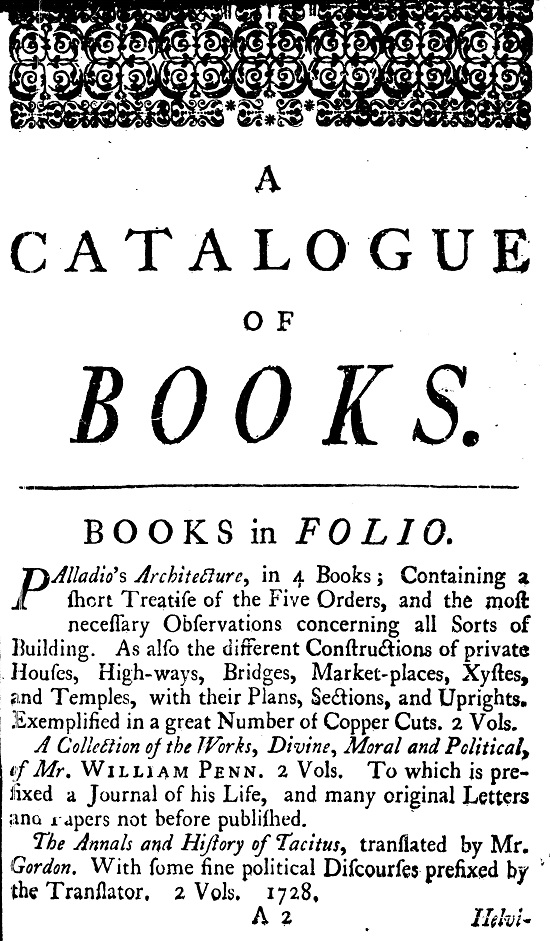

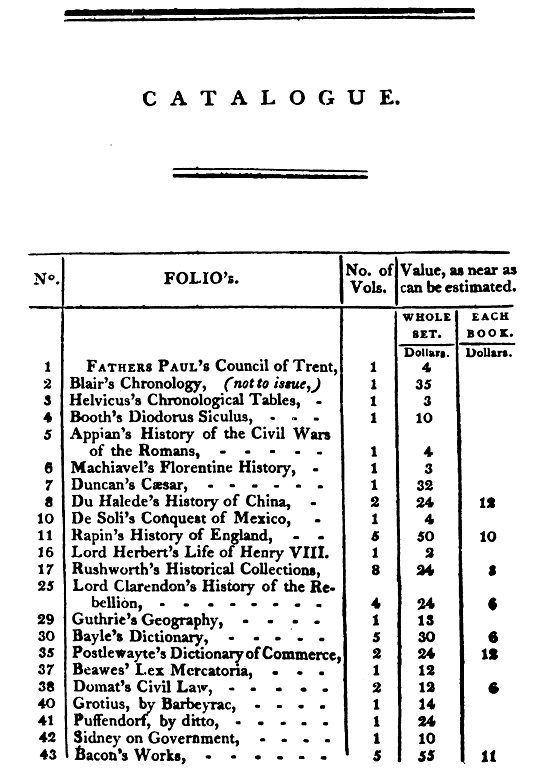

That company was the Library Company of Philadelphia, the inspiration of Benjamin Franklin. The same year, Franklin published “a catalogue of books belonging to the company…” which members could borrow to read at their leisure—a rare luxury in a time when books were expensive and difficult to come by.

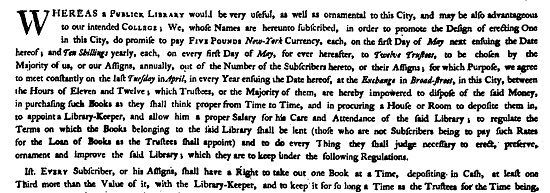

Thirteen years later another broadside, this time from New York City, proposed a subscription program to finance a public library. These important institutions were still not free, although their fees were relatively modest for Americans of comfortable financial means.

Meanwhile, the Library Company of Philadelphia continued occasionally to publish catalogs of their holdings. In 1807, Franklin’s heirs released an expanded account: “A catalogue of the books belonging to the Library Company of Philadelphia, to which is prefixed, a short account of the institution, with the charter, laws, and regulations.”

The Library Company was not alone. In 1806, the Bingham Library for Youth produced a catalogue of their collection.

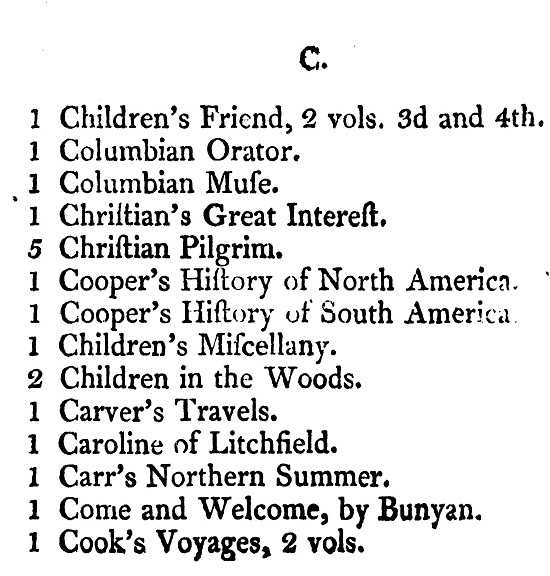

More of these early compendia can be found in America’s Historical Imprints, including examples issued by the Franklin Society in Amherst, New Hampshire, dated 1808, the Library Company of Baltimore, and “the library established in the Capitol at the city of Washington for the two houses of Congress”—later the Library of Congress.

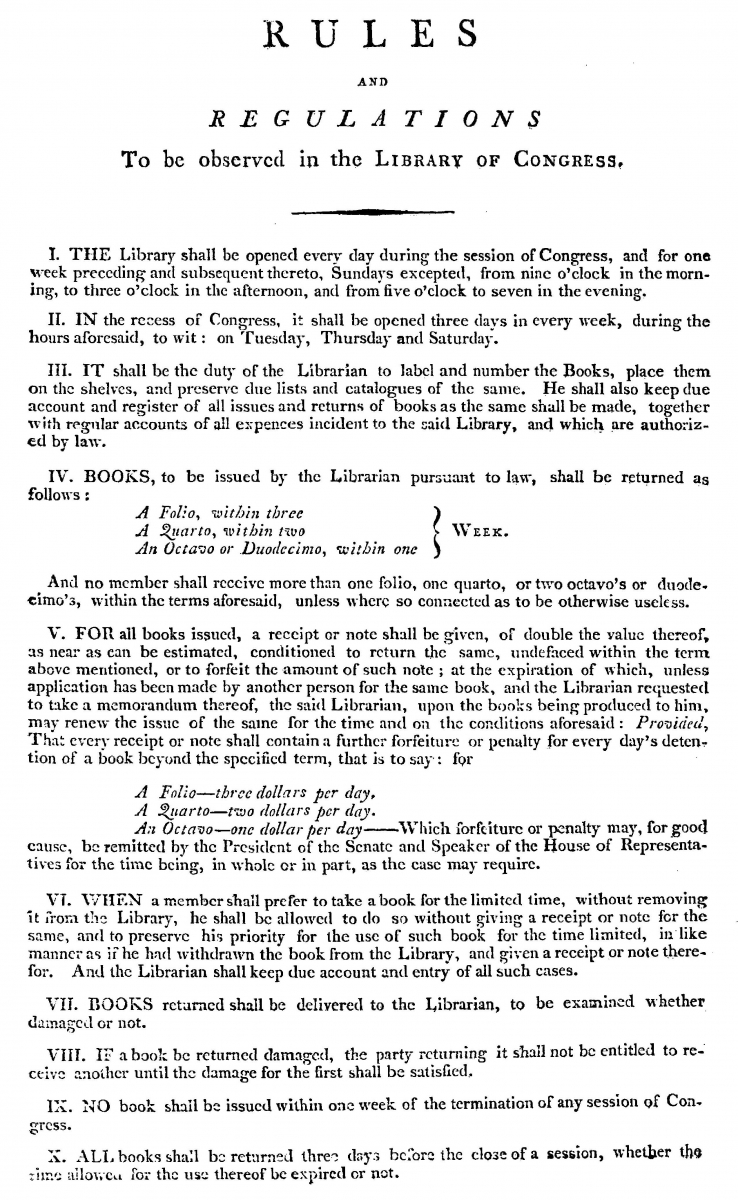

The Library of Congress also published its “rules and regulations to be observed…”, as did many other libraries. Among them were the “Regulations of New-Bedford Library” in New Bedford, Massachusetts; the Social Law Library, in Boston; and the Boston Public Library.

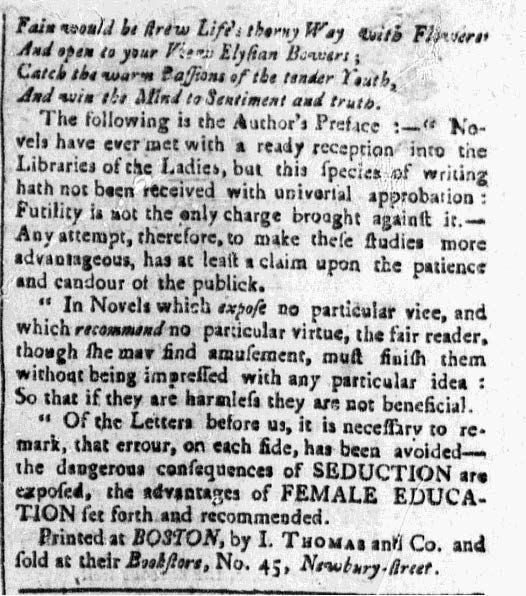

These early compendiums and regulations offer fascinating insight into the culture of early libraries. Those that included novels in their collections, for example, could be subject to criticism. In 1789, the Herald of Freedom, a Boston newspaper, published an article which was tepid at best—and possibly derisive—about the inclusion of novels in “Libraries for the Ladies.” The article asserted that “this species of writing hath not been received with universal approbation: Futility is not the only charge brought against it.”

In 1811—the same year Jane Austen published her first novel Sense and Sensibility—the Trenton Federalist ran a column praising the demise of the novel. The author wrote that “the contemptible fictions and novels which not long since engrossed the attention of readers of almost every age and class, are manifestly sinking into disrepute and neglect.”

Despite the ceaseless popularity of novels in libraries and private collections, newspaper columnists were loathe to retract this position. More than sixty years later, in 1874, the Cincinnati Gazette ran an opinionated column that began:

It must be confessed that novel reading is about the laziest semblance of occupation that can be indulged in; the mind of the reader being as nearly in a state of absolute inexertion as is consistent with the reception of ideas.

If people are foolish enough to buy this dross, the writer could accept it, “but should the public money, or the money of public benefactors be spent to provide people with such reading?” Clearly, he believed, it should not. The writer concludes:

Public libraries are not in the nature of book clubs, which must supply just what their members demand; and it is at least a serious question whether much of the flimsy and prurient fiction that cumbers their shelves might not, with propriety as well as profit to their readers, be excluded.

Americans also founded audience-specific libraries. Many of the earlier of these were designed for apprentices. An 1820 article in Boston’s Columbian Centinel was enthusiastic about serving this population: “Every child, of ever so poor connexions [sic] is here educated!”

Soon, libraries purposed for a wider variety of people began to spread. In 1820, the Agricultural Intelligencer, and Mechanic Register of Philadelphia announced that “Apprentices Libraries have been commenced at Philadelphia and New-York. At Philadelphia 24 Managers are appointed, who are enjoined carefully to exclude every work of an immoral tendency.”

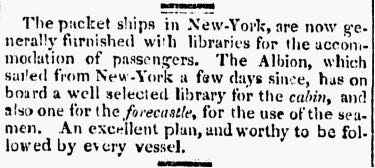

Other contemporary publications announced the establishment of libraries meant specifically for mechanics, farmers, abolitionists, police, women, and passengers on trains and steamboats, among many others.

While generally accessible, these specialty libraries usually received some sort of membership or usage fee. Others were restricted to particular patrons. In each case, it appears the founders were guided by the conviction that these populations could be uplifted by access to knowledge which would redound to the progress and common welfare of society, and as such, only practical or uplifting books were included.

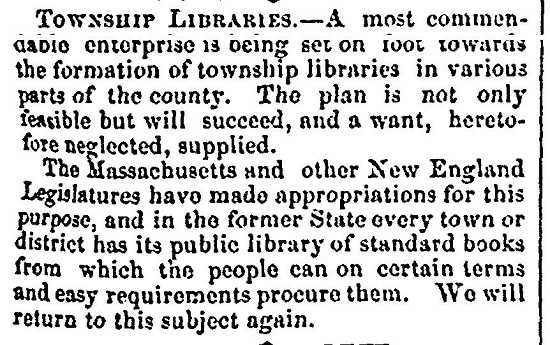

The turning point toward truly public, free libraries may be marked by articles such as the one published on January 1, 1868, in the Washington Reporter, from Washington, Pennsylvania. It refers to a plan to establish “township libraries in various parts of the count[r]y,” and notes that “the Massachusetts and other New England Legislatures have made appropriations for this purpose, and in the former State every town or district has its public library of standard books…”

Before long, a nationwide movement for public libraries blossomed, often with the support of newspapers, whose reporters were increasingly dependent on libraries to research their stories. In late 1872, the Cincinnati Daily Times editorialized:

A free public library is something which every city should have. Every [person] possessed of refined taste and liberal education appreciates a book; and though all persons do not have these requirements, a free library will contribute largely to their attainment….Let us have free public libraries, and by-and-by, when the struggle for wealth—which now seems to so nearly absorb the entire time and energies of our people—shall have given place, as it eventually will, to a taste for a better acquaintance with books, we shall be in condition to gratify a reasonable and healthy demand in that behalf.

2. A national library rises from the ashes

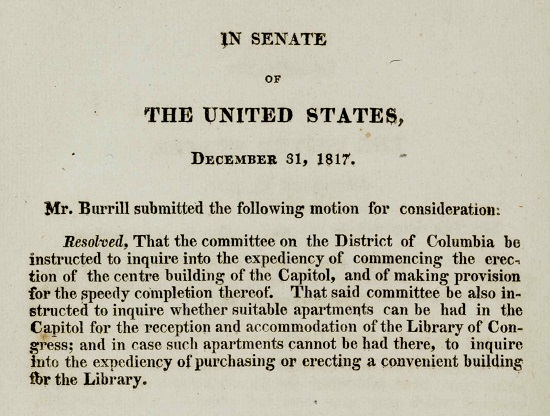

At the same time that municipalities were improving citizens’ access to literature, Americans were also beginning to establish a national library in Washington, D.C. The U.S. Congressional Serial Set captures the trials and tribulations of the Library of Congress. In 1817, for instance, a motion was made to

inquire into the expediency of commencing the erection of the centre [sic] building of the Capitol….inquire whether suitable apartments can be had in the Capitol for the reception and accommodation of the Library of Congress; and in case such apartments cannot be had there, to inquire into the expediency of purchasing or erecting a convenient building for the Library.

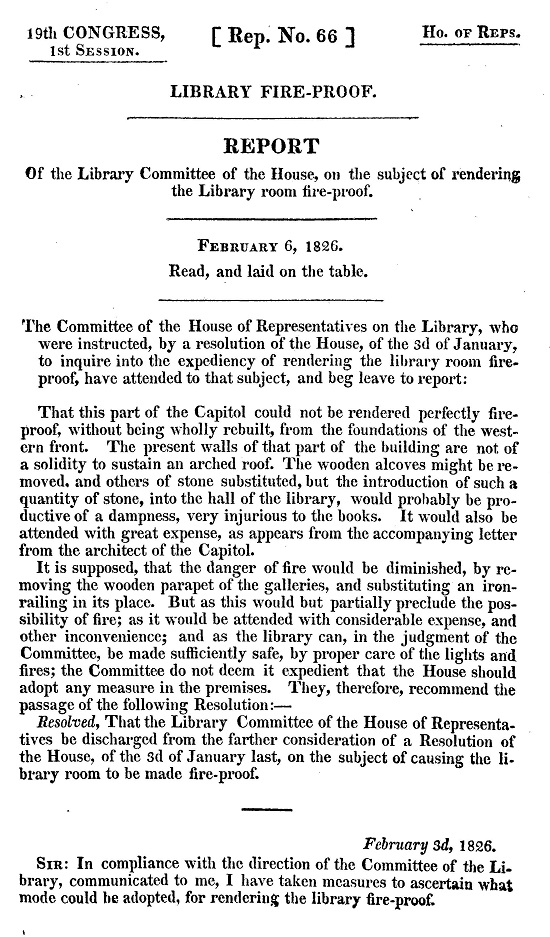

Despite this motion, the Library of Congress remained within the Capitol for another 80 years, beset by problems of space and the depredations of war and fire. In 1814, the British burned the building. In 1826 the Committee of the House of Representatives on the Library submitted a report in response to “a resolution of the House, of the 3d of January to inquire into the expediency of rendering the library room fire-proof…” They concluded that it was not necessary since “the library can, in the judgment of the Committee, be made sufficiently safe, by proper care of the lights and fires” and that they “do not deem it expedient that the House should adopt any measure in the premises.”

This decision sufficed for twenty-five years. Then, in 1851, fire erupted again, destroying much of the collection, including books from Thomas Jefferson’s library. After the devastating 1851 fire, the Senate Committee on Public Buildings reported on “a resolution directing them to inquire into the expediency of enlarging, repairing and refitting the principal apartment lately occupied by the library of the Congress, so that the same may be entirely fire-proof and capable of extension in harmony with the general plan of the capitol…” They concluded that because “of the necessity for some immediate provision to meet the want of a Congressional library…” hence it is “advisable to repair at once the former library room…”

Although the library was largely repaired, the need for more space became an intractable problem. By 1876, the Joint Committee on the Library of Congress issued a report committed to the “the erection of a separate building for the National Library…”

Congress began the long process of acquiring land, commissioning architectural plans, and allocating funds for a separate building. This process is well documented by the Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army.

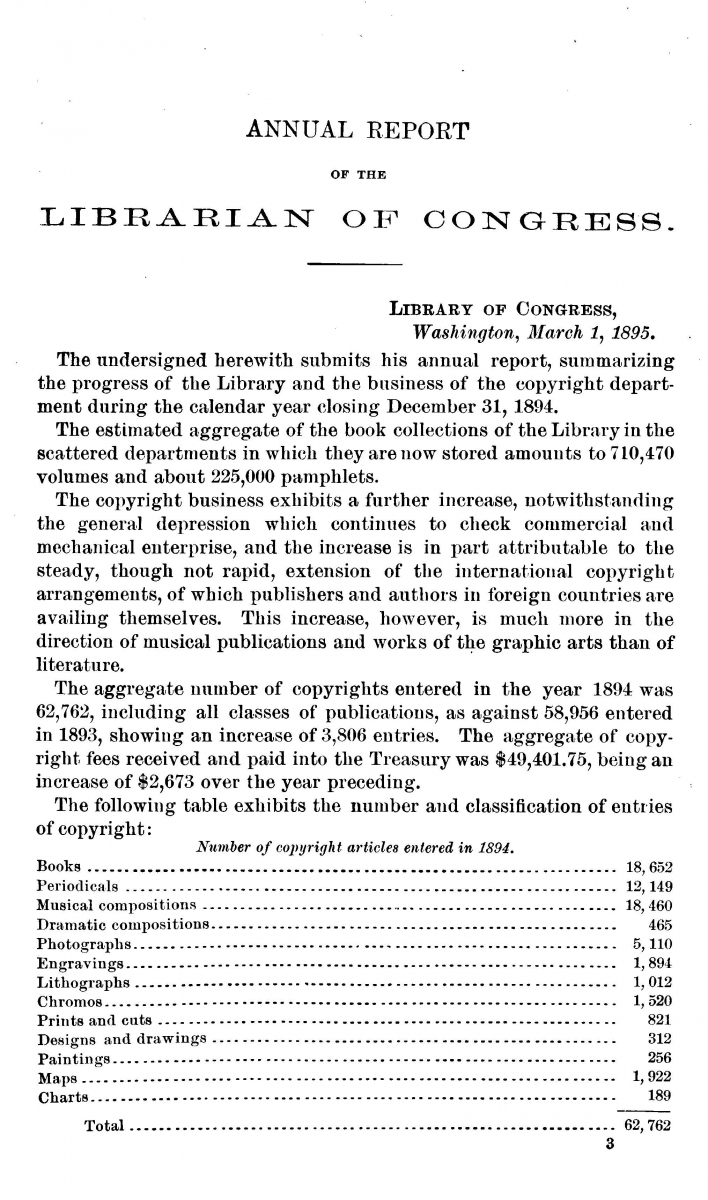

Additionally, the annual reports of the Librarian of Congress follow the development of the collection and the construction, interior fixtures, staffing, and other related matters of moving the Library to its new home in the Jefferson Building, a task that was finally completed in 1897:

The work was accomplished as follows: All transfer of the matter was made by means of wooden boxes, consisting of open trays and handbarrows. These were loaded and handled by workmen who generally carried them on the shoulder along the floors or upstairs, but the more heavily loaded boxes and all handbarrows were carried by two men, one at each end….they were piled into wagons going between the Capitol and the Library building…

3. An influx of riches

Toward the end of the 19th century, the expanding establishment of public libraries was profoundly affected by the philanthropy of Andrew Carnegie, one of America’s wealthiest men. Between 1883 and 1929, 1,689 libraries in the United States were built thanks to Carnegie’s largess.

Carnegie opened his first library in Dunfermline, Scotland—his birthplace. In 1889, the first Carnegie-funded library in America opened in Braddock, Pennsylvania, where a large Carnegie Steel plant was located. For the next thirteen years all of the libraries endowed by Carnegie were similarly in southwestern Pennsylvania, with one exception in Fairfield, Iowa, which was commissioned in 1892.

The New York Herald published an article of Carnegie’s views on public libraries on March 9, 1890.

No city can afford to be without free circulating libraries any more than it can afford to be without public schools,” he said. “We recognize that children must be taught in a republic. After they are taught at school the library stretches out its arms into their homes and keeps and leads them in the path of future education.

Newspapers around the country raved about Carnegie’s generosity. Western Massachusetts’ Springfield Republican reported that

An idea of how the public is profiting through Andrew Carnegie’s generosity in establishing free libraries may be gleaned from the fact that Mr. Carnegie has so far given $6,174,500 for this purpose. With this sum 24 free libraries have been established in this country or in Scotland. Further, there are conditional offers now outstanding, all of which will, of course, be accepted, amounting to no less than $2,000,000.

In early 1902 the Omaha World-Herald announced that Carnegie “had just given away thirty-eight new libraries” including “one in Nebraska, seven in Iowa, two in South Dakota.”

Not even fictional characters could escape Carnegie’s influence. Mr. Dooley, a fictional Irish bartender invented by the journalist Finley Peter Dunne, was featured in a column carried by newspapers nationwide. The Anaconda Standard in Anaconda, Montana, carried one such column in its January 18, 1903, issue, written in Dunne’s representation of an Irish accent.

“Has Andrew Carnegie given ye a libry yet?” asked Mr. Dooley. “Not that I know iv,” said Mr. Hennessy.” “He will,” said Mr. Dooley. “Ye’ll not escape him. Before he dies he hopes to crowd a libry on ivry man, woman an’ child in th’ country. He’s givi’ thim to cities, towns and villages, an’ whistlin’ stations. Theyre tearin’ down gas houses an’ poorhouses to put up libries. Before another year ivry house in Pittsburg that ain’t a blast furnace will be a Carnaygie libry.”

Still, Carnegie’s beneficence was not universally applauded. The Trenton Evening Times reported on August 7, 1901, that

The Central Labor Union of Easton and vicinity representing twenty-five local unions and ten thousand working men, have adopted resolutions protesting against the erection of a public library which is a gift of Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie was roundly denounced by the speakers as the foe of laboring men. The members of the union agree not to enter the library after its erection.

Unions also protested how more and more villages, towns, and cities were accepting Carnegie’s terms for operating the libraries he paid for. And Carnegie appears to have straddled the overt racism of his age. According to the Savannah Tribune in South Carolina, Carnegie provided “$25,000 for the addition to our main building of the public library, and $25,000 for the erection of a colored branch.” Their headline read “Carnegie is Generous Donates $50,000 for Public Libraries Colored People to Get $25,000.”

Carnegie’s scheme had interesting effects. The Cleveland Plain Dealer reported on February 23, 1902, that

Mr. Carnegie has established, within the past two years, more than 300 libraries in cities and towns in almost every state and territory in the union, and is planning to establish many more in the future. At the same time there has been a great boom in the book trade, believed to be in a measure due to Mr. Carnegie’s munificence. Publishers and book jobbers in New York city agree that the enormous sum given by Mr. Carnegie has done much to stimulate the trade and to increase the demand for books.

In an interview reported in South Dakota’s Aberdeen Daily News, Carnegie himself declared:

I think it will be found, that far from being a philanthropist I am engaged in making the best bargains of my life. For instance, when New York had been given over a million pounds for seventy-two libraries I succeeded in getting a pledge from her that she would furnish sites and maintain these libraries forever.

Today, many of these libraries still stand—testaments to the influx of Carnegie’s fortune, but also to the industry and thirst for learning of the American people.

Note: Several Readex digital products were used to research this broad topic. For information about making these products available in your library, please contact Readex.