“With all the wrongs and neglects of her past, with all the weakness, the debasement, the moral thralldom of her present, the black woman of to-day stands mute and wondering at the Herculean task devolving upon her. But the cycles wait for her. No other hand can move the lever. She must be loosed from her bands and set to work.”

— Anna Julia Cooper, A Voice from the South (1892)

“The negro as an ‘alien’ race, as a ‘problem,’ as an ‘industrial factor,’ as ‘ex-slaves,’ as ‘ignorant’ etc., are well known and instantly recognized; but colored women as mothers, as home-makers, as the center and source of the social life of the race have received little or no attention”

— Fannie Barrier Williams in A New Negro for a New Century (1900)

“Only the BLACK WOMAN can say ‘when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.’”

— Anna Julia Cooper, A Voice from the South (1892)

“This is indeed the women’s era, and we are coming.”

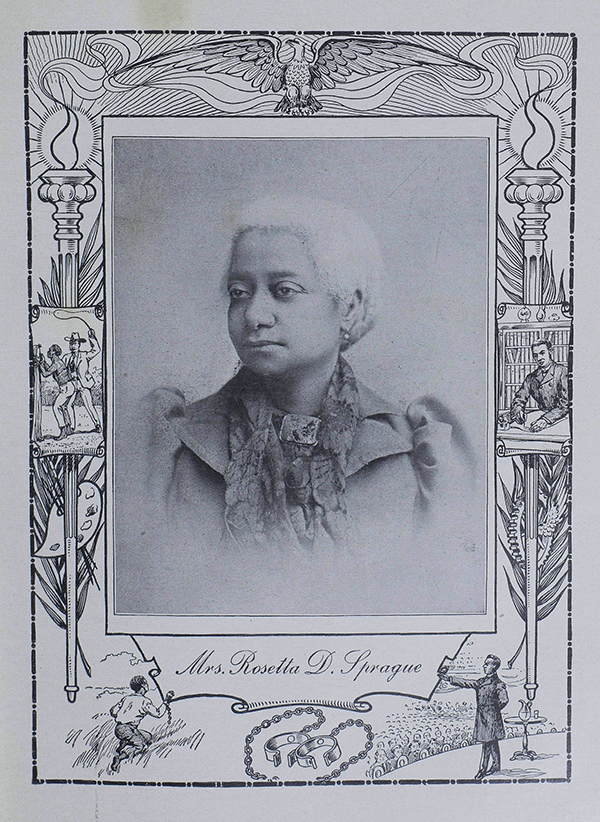

— Rosetta Douglass-Sprague, quoted in A History of the Club Movement Among the Colored Women of the United States of America(1902)

Introduction

Historical sources in the Afro-Americana Imprints collection illuminate Black women’s lives and activism in the Progressive era. The digital collection is particularly strong in publications related to Black club women—educated, mostly middle-class women who banded together to focus their collective power on uplifting and improving Black lives. These sources chart Black uplift and the central importance of women in that climb. One of the treasures of the collection is a set of sociological accounts of Black domestic servants and their employers. Through a thriving print culture, Black writers commemorated women’s accomplishments and, in so doing, signaled the unlimited potential of Black women and men.

While Afro-Americana Imprints has obvious value for history courses, it also has relevance for courses that deal directly with today’s world (for instance, Black Studies, Sociology, and Women’s Studies), providing documents to help link past and present. For history courses, sources in the database can be used in the U.S. history survey and specialist courses in women’s history, Black history, labor history, and the Progressive era.

What follows are suggestions for how the database might be used to help students understand the historical roots of contemporary issues, and for understanding the past on its own terms. For history courses, three main Progressive-era topics are highlighted below: the Black women’s club movement; Black women’s education, achievement, and leadership; and sociological studies of domestic workers. A bibliography of scholarship on relevant topics is at the end of this essay.

Connecting Past with Present

Afro-Americana Imprints provides abundant opportunities to help students connect the present to the past and identify both continuities and change. These historical sources can be paired with contemporary scholarship or journalism to trace those connections.

Sources that detail Black women’s activism of the Progressive Era provide context for more recent activist experiences. Just for instance, Audre Lord’s 1981 address to the National Women’s Studies Association Conference, published in the collection Sister Outsider, highlights relations between Black and white women activists and scholars. Brittney Cooper’s Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower is one of many more recent voices. Historical sources about domestic workers in the Progressive Era could be paired with Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo’s study of their twenty-first-century counterparts, Doméstica: Immigrant Workers Cleaning and Caring in the Shadows of Affluence.

One of the things that distinguished the activism of Black club women from white club women in the Progressive era was their focus on issues that did not appear to pertain directly to women, but instead focused on achieving equality for all Black Americans. Connecting past with present, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century readings about the convict labor system of the South could be paired with selections from Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow. The 1902 observation of the Lucy Thurmon Union that “four-fifths of the prisoners in our jail and workhouse are of our race….” provides important context for the argument that race slavery lives on in the present, facilitated by the “school-to-prison pipeline.” [A History of the Club Movement, p. 77]. Students could be invited to examine the history of lynching in the U.S. in relation to the 2020 murder of Ahmaud Arbery and other similar cases. Selections from Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America could be paired with Progressive-era sources that discuss the ideas that helped maintain the oppression of Black Americans. These suggestions are by no means exhaustive.

The Black Women’s Club Movement: Sources for Discussion, Essays, and Research Projects

The history of the Black women’s club movement is relevant to any U.S. or Black history courses that deal with the Progressive Era, including the U.S. survey and specialist courses on histories of women, labor, and education.

Some of the causes that motivated Black women’s activism were shared with white women activists—temperance, for instance. Many others were unique to Black experiences. Black club women challenged oppressive white ideas about Blackness as much as they challenged unequal material, social, legal, and political conditions. Black women’s clubs exposed and publicized major obstructions to Black equality, argued eloquently for specific changes, and suggested, through their abundance of determination, that change was possible.

This section is divided into three subsections. The first includes a variety of sources that provide a foundation for understanding the Black women’s club movement, its intellectual life, and the range of women’s activities and activism. This list is extensive; instructors may choose any readings from the list in combination with a single question or selection of questions to guide students’ focus. The second section offers a case study of Black women’s efforts to join the white-run National Women’s Council, and the third provides a list of possible sources for essay assignments and research projects.

I. The Black Women’s Club Movement: A Call to Arms

Moore, The Colored Women and Girls of the South (1885), pp. 5-9.

Cooper, A Voice from the South (1892), pp. 27-38, 84-88, 91, 95-96, 100-103, 107-114, 253-270.

Hopkins, Contending Forces (1900), pp. 14-15.

Kletzing and Crogman, Progress of a Race (1900), pp. 171-172 and “The Colored Woman of To-Day,” pp. 196-207.

Williams, Fannie Barrier. “The Club Movement Among Colored Women of America” in Wood, A New Negro for a New Century (1900), pp. 379-428.

Sprague, Terrell, Bowser, and Pettey, “What Role is the Educated Negro Woman to Play in the Uplifting of Her Race,” in Culp, Twentieth-century Negro Literature (1902), pp. 167-185.

National Association of Colored Women, A History of the Club Movement Among the Colored Women of United States of America (1902), pp. 36-37, 41, 44-52, 56, 63-65, 92-118.

Report of the Woman’s Era Club of Boston in A History of the Club Movement Among the Colored Women of the United States of America (1902), pp. 115-118.

Questions

Q: According to these sources, what qualities characterized Black women? What was their value to American society? What were their powers and potential for achieving Black uplift?

Q: Where did middle-class Black women direct their energies? What did Black women identify as the most important obstacles to Black equality and challenges to be overcome?

Q: What do these authors identify as women’s role in achieving Black equality? What did they identify as the particular needs of Black women? What unique social power did women have?

Q: What did Black club women identify as some of the most pressing needs of Black communities and specific problems to be solved? What solutions did they suggest?

II. White Women, Opponents and Allies

Fannie Williams’s detailed account of the “Ruffin Incident” of 1900 offers a particularly valuable case study in the history of relations among Black and white club women. Williams provides a platform for the voices of Ruffin and the women of her club regarding events and debates that were widely covered in the popular press at the time. Another example of an incident in the relationships between Black and white women’s clubs and their members is provided in Anna Julia Cooper’s account of an 1891 Meeting of National Women’s Council in Washington D.C.

Cooper, A Voice from the South (1892), pp. 80-83.

Wood, A New Negro for a New Century (1900), pp. 391-392.

Williams, Fannie Barrier. “Club Movement Among Negro Women” in Gibson and Crogman, Progress of a Race, revised (1902), pp. 216-228.

Questions

Q: When Fannie Williams wrote, “there is the serious danger of being misrepresented” (p. 226), what was in danger of being misrepresented, and by whom?

Q: What kind of danger do you think Williams envisioned?

Q: What do you think she imagined as the consequences?

Q: According to Williams, what were white clubwomen’s specific fears about interracial cooperation?

Q: According to Williams, what were the effects of the publicity about the case?

Q: How does Williams characterize Black club women?

Q: According to Williams, what were the effects of the publicity about the case?

Q: How does Cooper’s account of white women’s attitudes towards Black women compare with the “Ruffin Incident”?

III. Sources for Black Women’s Club Movement Research Projects

Moore, Mrs. G. W. [Ella Sheppard]. The Colored Women and Girls of the South (1885), pp. 9-12.

Mossell, Mrs. N. F. [Gertrude Bustill]. The Work of the Afro-American Woman (1894).

Williams, Fannie Barrier. “The Club Movement Among Colored Women of America” and “The Clubs and Their Location in All the States of the National Association of Colored Women and Their Mission” in Wood, A New Negro for a New Century (1900), pp. 379-405, 406-428.

“The Colored Woman of To-Day” in Kletzing and Crogman, Progress of a Race (1900), pp. 191-228.

National Association of Colored Women, A History of the Club Movement Among the Colored Women of the United States of America (1902).

Williams, Fannie Barrier. “Club Movement Among Negro Women” in Gibson and Crogman, Progress of a Race, revised (1902), pp. 197-232.

Black Women’s Education, Achievement, and Leadership

Education

Black leaders recognized the necessity of education as a first step towards full social, legal, political, and economic equality. In the following sources, authors speak to this necessity and provide detailed snapshots of the many educational institutions that served Black communities. The project of uplifting through education relied heavily on the achievements of Black women who received college degrees and went on to become school teachers and administrators.

Sources

Cooper, “The Higher Education of Women” in A Voice from the South (1892), pp. 48-79.

Carter, The Black Side: A Partial History of the Business, Religious and Educational Side of the Negro in Atlanta, Ga. (1894), pp. 28-35 and various.

Wood, A New Negro for a New Century (1900), p. 424.

Culp, “What Role is the Educated Woman to Play in the Uplifting of Her Race?” in Twentieth-Century Negro Literature (1902), pp. 167-185.

Bureau of Education, Department of the Interior. Negro Education: A Study of the Private and Higher Schools for Colored People in the United States (1917), numerous entries; see, for instance, the entry for the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, Alabama, pp. 77-78 and Hampton Training School for Nurses, Virginia, p. 668.

Achievement and Leadership

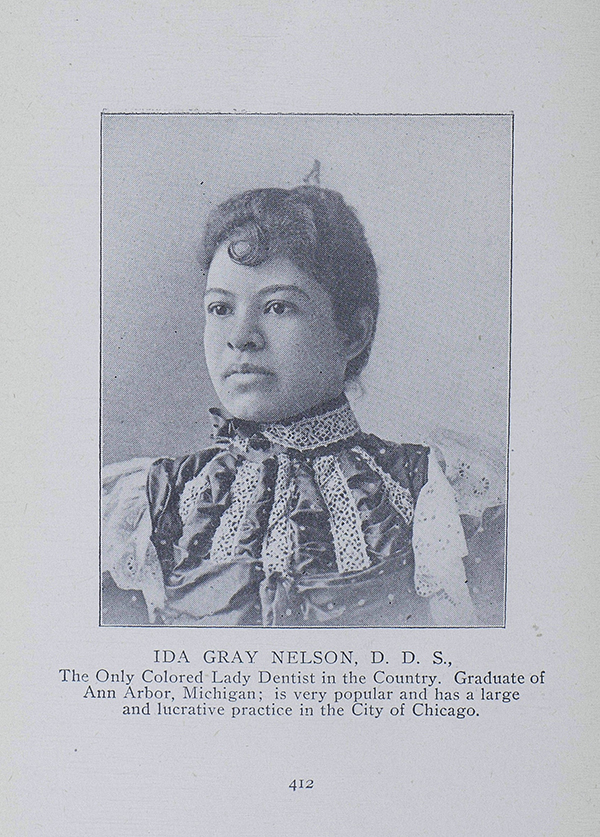

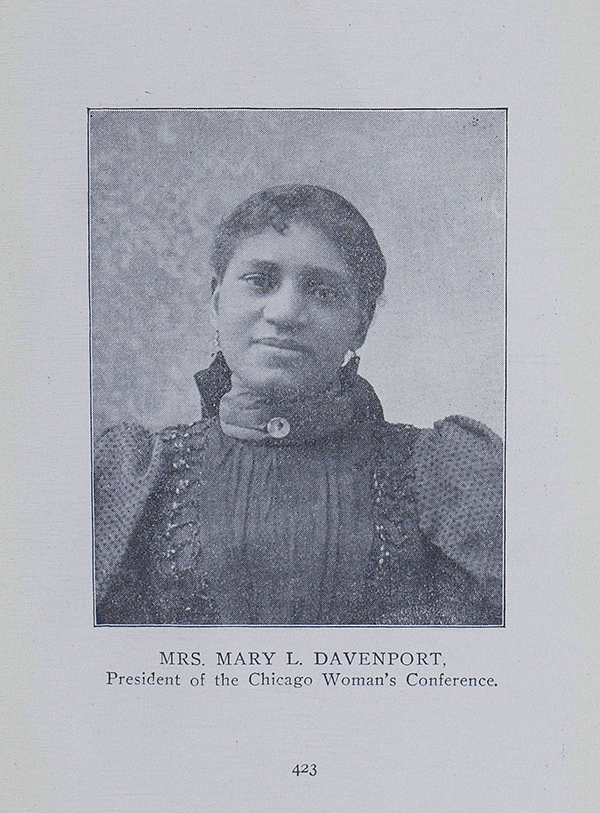

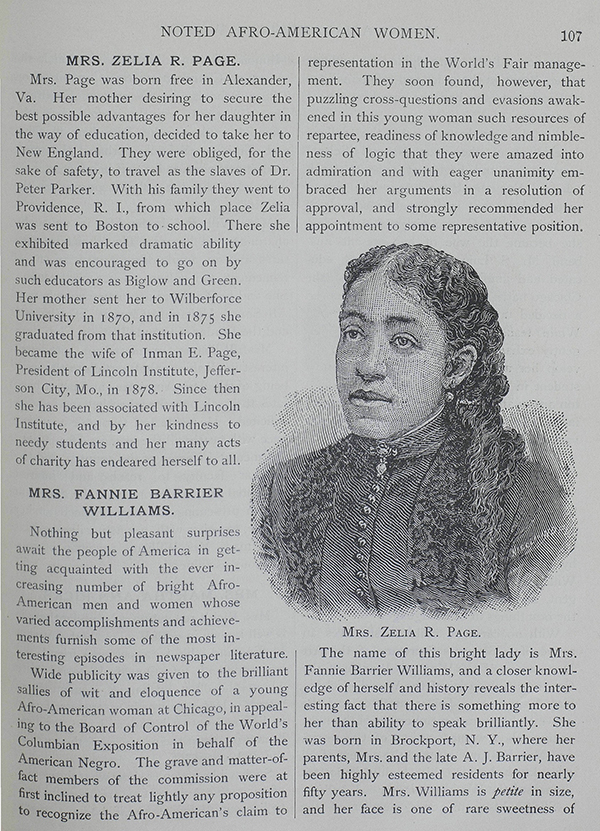

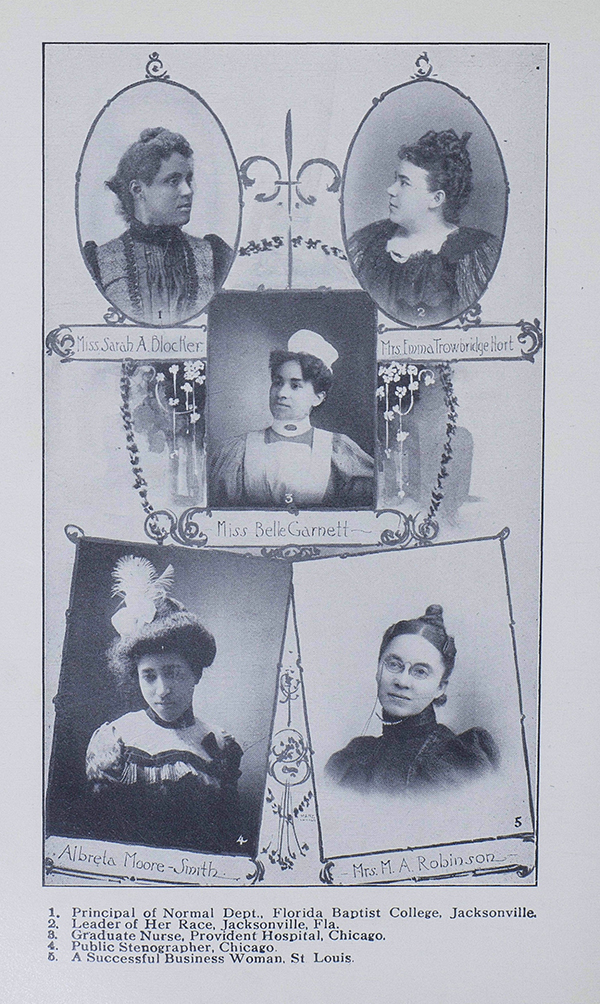

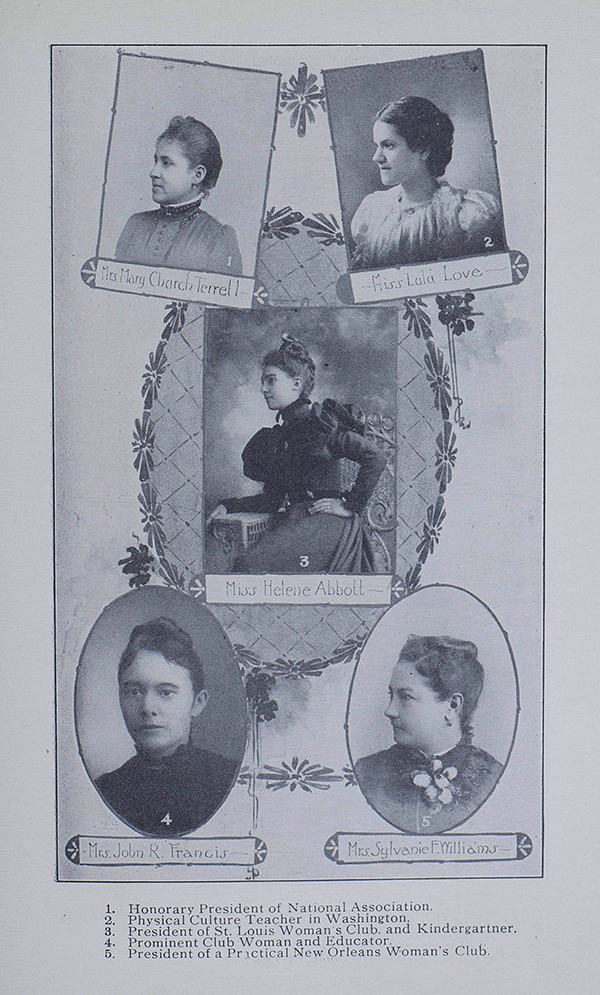

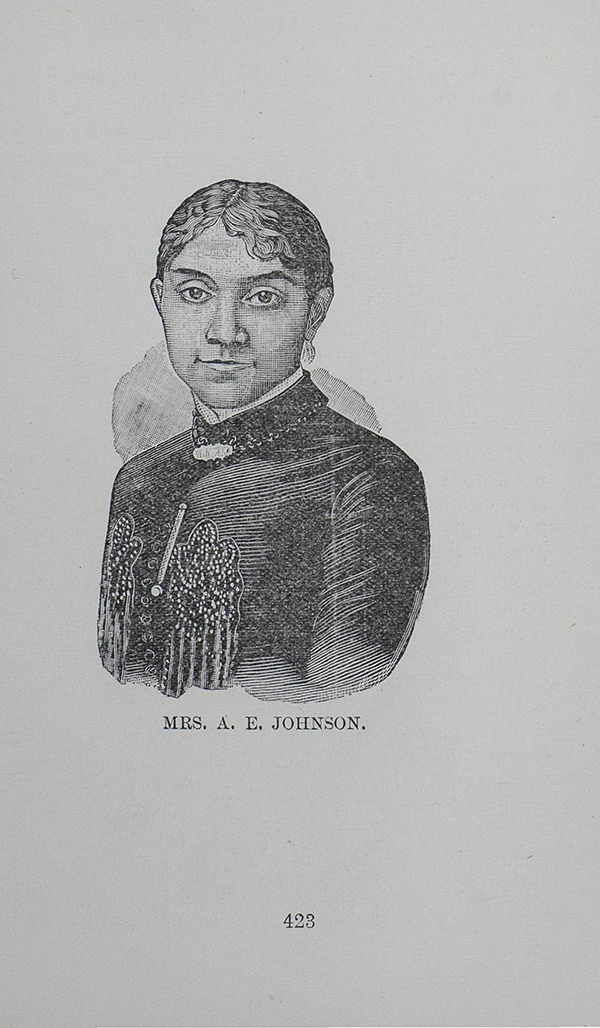

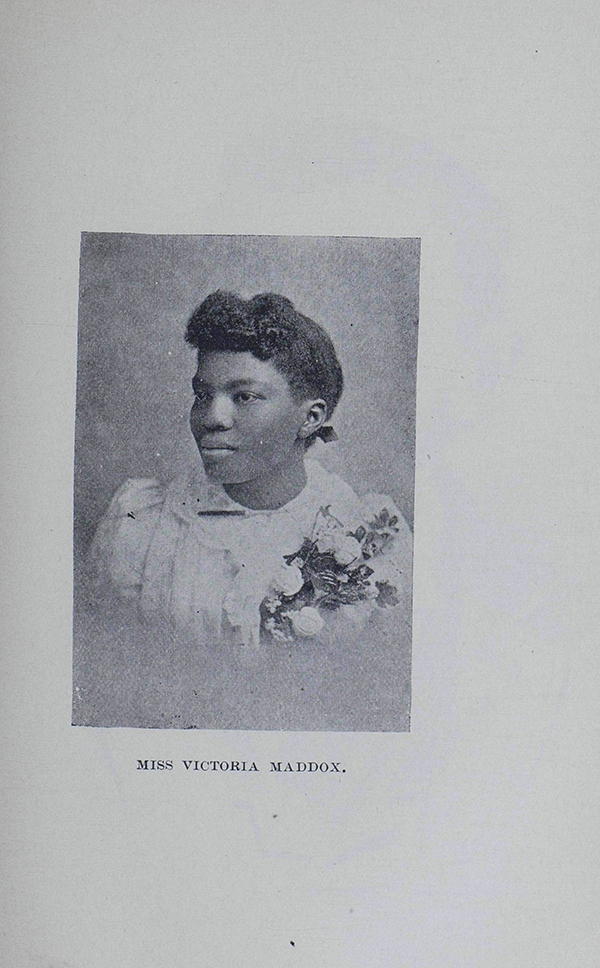

Detailed biographies of these educators and other Black woman leaders are also a particular strength of Afro-Americana Imprints. The database is rich with portraits of these role models, some still famous today, most largely forgotten. The presence of these narratives and images speaks of the importance of heralding women’s achievements and of pictorial representation. In a larger, white world of popular media in which disparagement of Blacks was the norm, such positive representations were vital not only for giving lie to the mainstream white mythology about Black character and potential, but also as exemplars to others in the climb towards Black equality.

Some of the women highlighted in these biographies began life in adverse and humble circumstances, others entered the world with significant privilege. Many received college educations, and all embraced middle-class cultural values. In addition to the following sources, numerous women can be found in the pages of Who’s Who of the Colored Race (1915, Frank Lincoln Mather, ed.).

Sources (entries with asterisks contain portraits, including those that illustrate this article):

*“Afro-American Women in Journalism” in Penn, The Afro-American Press and Its Editors (1891), pp. 367-427.

*Carter, Rev. E. R. The Black Side: A Partial History of the Business, Religious and Educational Side of the Negro in Atlanta, Ga. (1894), pp. 35-37, 126-128, 236-238; portraits follow pp. 40 and 120.

Mossell, Mrs. N. F. [Gertrude Bustill], The Work of the Afro-American Woman (1894). Includes numerous women educators; writers and journalists; doctors, nurses, and the first Black woman dentist; women in law; Christian evangelicals and mission workers; elocutionists, pianists, composers, playwrights, philanthropists.

*“Noted Afro-American Women and Their Achievements” in Northrop, The College of Life, or Practical Self-Educator: A Manual of Self-Improvement for the Colored Race (1896), pp. 95-110.

* Kletzing and Crogman, Progress of a Race (1900), pp. 191-228, 487-490, 533-534, 556-567, 563-569, 574-575, 577.

*Wood, A New Negro for a New Century (1900), pp. 378-428

*Culp, Twentieth-Century Negro Literature (1902); biographies and photographs between pp. 16-17, 20-21, 138-139, 166-167, 172-173, 176-177, 246-247, 264-265, 304-305.

*“Prominent Colored Women” in Richings, Evidences of Progress Among Colored People (1897), pp. 411-428.

Black Women’s Labor as Domestic Workers, North and South: Primary Sources for Research Projects

Any of the preceding suggestions could provide a starting point for student research projects about the history of Black women. Another group of sources in Afro-Americana Imprints provide substantial information about Black women who worked as domestic servants in urban Georgia and Philadelphia. This includes statistical data as well as information about working conditions and attitudes of Black employers towards their servants. Reading survey responses of employers against the grain also reveals the attitudes, perceptions, and expectations of domestic workers. Sociologist Isabel Eaton is one of the contributors. The documentary film, Freedom Bags (1991), which features interviews with Black domestic workers, would make an excellent supplement.

Sources

National Association of Colored Women, A History of the Club Movement Among the Colored Women of United States of America (1902), pp. 45-46.

Eaton, “Special Report on Negro Domestic Service in the Seventh Ward” in The Philadelphia Negro (1899), pp. 427-509 and maps facing p. 1 and p. 60.

Woofter, “Occupations,” “Domestic Service,” and domestic service questionnaire. The Negroes of Athens, Georgia (1913), ch. 6, pp. 37-42; ch. 7, pp. 43-49; p. 58.

Secondary Sources

Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press (2010, 2012).

Bay, Mia. To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells. Hill and Wang (2010).

Bay, Mia, Farah J. Griffin, Martha S. Jones, and Barbara D. Savage. Toward an Intellectual History of Black Women. University of North Carolina Press (2015).

Cooper, Brittney. Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women. University of Illinois Press (2017).

Davis, Angela Y. Women, Race, & Class. Random House (1981).

Equal Justice Initiative. Lynching in America. https://eji.org/reports/lynching-in-america/

Feimster, Crystal N. Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching. Harvard University Press (2011).

Giddings, Paula J. When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America. William Morrow (1984, 1996).

Gilmore, Glenda. “Diplomatic Women” (ch. 6, 147-176), Gender and Jim Crow: Women and Politics of White Supremacy, 1896-1920. 2nd ed. University of North Carolina Press (2019).

Hondagneu-Sotelo, Pierrette. Doméstica: Immigrant Workers Cleaning and Caring in the Shadows of Affluence. University of California Press (2007).

hooks, bell. Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, 2nd ed. Routledge (2014).

Hunter, Tera W. To 'Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors After the Civil War. Harvard University Press (1998).

Hunter, Tera W. “’The “Brotherly Love”’ for Which This City Is Proverbial Should Extend to All’: The Everyday Lives of Working-Class Women in Philadelphia and Atlanta in the 1890s.” In W. E. B. Du Bois, Race, and the City: "The Philadelphia Negro" and Its Legacy, edited by Michael B. Katz and Thomas J. Sugrue. University of Pennsylvania Press (1998), pp. 127-151.

Kendi, Ibram X. Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. Bold Type Books (2017).

Knupfer, Anne Meis. “Toward a Tenderer Humanity and a Nobler Womanhood: African American Women’s Clubs in Chicago, 1890 to 1920” in Journal of Women’s History 7:3 (1995), pp. 58-76.

Lerner, Gerda. "Early Community Work of Black Club Women." The Journal of Negro History 59:2 (April 1974), pp. 158–167.

Logan, Shirley Wilson. We are Coming: The Persuasive Discourse of Nineteenth-century Black Women. Southern Illinois University Press (1999).

Lorde, Audre. “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press (2007), pp. 124-133.

Parker, Alison. Articulating Rights: Nineteenth-Century American Women on Race, Reform, and the State. Northern Illinois University Press (2010).

Robnett, Belinda. Living for the Revolution: Black Feminist Organizations, 1968–1980, revised edition, Oxford University Press (1997).

Sharpless, Rebecca. Cooking in Other Women’s Kitchens: Domestic Workers in the South, 1865-1960. University of North Carolina Press (2010).

Shaw, Stephanie J. What a Woman Ought to Be and to Do: Black Professional Women Workers During the Jim Crow Era. The University of Chicago Press (1996).

Springer, Kimberly. Living for the Revolution: Black Feminist Organizations, 1968–1980. Duke University Press (2005).

White, Deborah Gray. Too Heavy a Load: Black Women in Defense of Themselves, 1894-1994 (1999).