Most important, Stowe’s text allows whites to talk to other whites about the personal and national issues surrounding the slave [and current] black experience and establishes the character types usually associated with African Americans.

Sophia Contave, “Who Gets to Create the Lasting Images?”

During the very first session of my Spring 2015 graduate seminar on “Revising Uncle Tom's Cabin: 19th-Century African American Novelists Respond,” I asked the students enrolled to begin generating ideas for the collaboratively authored papers they would later publish in The Readex Report. To stimulate use of the online resource Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922: From the Library Company of Philadelphia, I assigned a focused timeline project. Because my seminar first met on Thursday, January 22, 2015, the course objectives included: “[To] Help students learn to situate themselves in the academy as raced sociopolitical beings.” To this goal, I added two online resources, Race—The Power of an Illusion and 12 Things White People Can Do Now Because Ferguson. If I were to generate now a timeline pinpointing political and cultural events surrounding the months during which my seminar students generated very different timelines, my own would include:

- July 17, 2014: Eric Garner (black) choked to death by police officer Daniel Pantaleo (white) in Staten Island, New York

- August 9, 2014: Michael Brown (black) fatally shot by police officer Darren Wilson (white) in Ferguson, Missouri

- November 22, 2014:Tamir Rice (black) fatally shot by police officer Timothy Loehmann (white) in Cleveland, Ohio

- November 24, 2014: Saint Louis County grand jury decides against indicting Darren Wilson

- December 3, 2014: New York grand jury decides against indicting Daniel Pantaleo

- March 4, 2015: U.S. Department of Justice determines Wilson shot Brown in self-defense

- April 4, 2015: Walter Scott (black) fatally shot by police officer Michael Slager (white) in North Charleston, South Carolina

- April 12, 2015: Freddie Gray (black) slips into coma while in police custody in Baltimore, Maryland, having been beaten and arrested by a multiracial corps of police officers

- April 19, 2015: Freddie Gray dies from fatal wounds.

I start with this timeline to emphasize the political contexts that surrounded and permeated our seminar.[1] As always, I assigned recent theories of racial identity and racial attitudes formation for discussion during the first several class sessions.[2] Each term, my current students (almost exclusively literature heads) and I work through the instruments, scales, and measures of psychological analyses such as the White Racial Identity Attitudes Scale (WRIAS), the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MMRI), and the Implicit Association Test (IAT). In other words, while I consistently begin my courses with a plunge into race, racial biases, and intersectional identities—often some students’ first such exposure—during Spring 2015, these early lessons took on added significance. Although we did not often explicitly reference the deaths of African Americans at the hands of police violence and the media coverage (for better and worse) of the many protests insisting around the nation that “Black Lives Matter,” the seminar had begun with thoughtful interrogations of our respective privileges and oppressions. Concentrating as we did on the decades between 1850 and 1900, we could not help but meditate on the impact—and reiteration—of slavery’s peculiar atrocities on the contemporary moment. Such reflection evolved by design; I had planned its occurrence for this instantiation of African American literature.

However, something I did not plan occurred when my students began searching Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922,for seminar project topics: From among the thousands of documents in the Readex collection, they invariably gravitated toward texts about black people by white authors. Strikingly, since midterm our seminar demographics had settled into a population of five white women, an African American woman, a Chicana, and a multiracial woman; I myself made for a second black woman. Further, all of the students, save the one white doctoral student, are pursuing an MA degree; only my black student was not affiliated with UTSA’s English graduate program. Although we had read Uncle Tom’s Cabin at the outset of the course, we had spent most of the term studying novels by William Wells Brown, Sutton Griggs, Pauline Hopkins, and Harriet E. Wilson. We also read together Toni Morrison’s theoretical treatise Playing in the Dark and one of its 19th-century antecedents Victoria Earle Matthews’s “The Value of Race Literature.” In addition, the students had spent numerous hours researching black historical events surrounding Clotel, Our Nig, Imperium in Imperio, and Of One Blood, and organizing these investigations into individual multimedia timeline presentations.

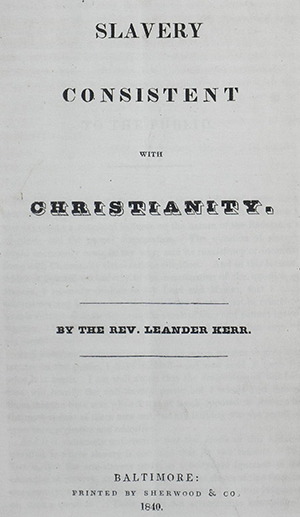

Yet after months of immersion into carefully selected texts written by African Americans, all eight students ended up primarily exploring white authors, white supremacist documents, sentimental pathologies of Africans, and other discourses promoting white power when they turned, collectively and individually, to Afro-Americana Imprints to write Readex Report essays. Although the documents they eventually selected for the lesson plans within their essays included 19th-century black Colored Conventions and women’s conventions participants as well as Morrison and Anna Julia Cooper, even the TED Talk on contemporary slavery they recommend to educators is by a white man.[3] Notably, one of the three writing teams included the African American student as a member; another team included both of the other women of color. Moreover, for an earlier assignment (a solo authored analysis of an African American Imprints document of their choice), these three students, too, had selected white discourses: Ariel’s “The Negro: What is His Ethnological status?” (1867); A. Benezet’s A caution and warning to Great Britain and her colonies in a short representation of the calamitous state of the enslaved Negroes in the British dominions (1766); R. J. Dunglison’s Statistics of insanity in the United States (1860); Henry M. Field’s Bright Skies and Dark Shadows (1890); Leander Ker’s Slavery Consistent with Christianity (1840); and the New England … Friends’ “An Appeal to the Professors of Christianity, in the Southern States and Elsewhere, on the Subject of Slavery” (1842). That is, the students of color in our seminar also centered their course writing on white theorizations of blackness and black people. Observing sans judgment, I repeatedly felt fascinated by the ideas and concerns that fascinated all eight students.

After the semester ended, I read in their course evaluations that they deeply appreciated the exposure to the black literature the seminar afforded and that they had been exhilarated to learn more about black literary tropes and strategies. In the evaluations each expressed gratitude for the requirement to rethink racialized ideas they had assumed they had already neatly sorted and/ or had politely pretended no longer mattered. In other words, they consistently demonstrated enthrallment with literary works by African Americans, be those texts about slavery or abolition, black maternity and power, black self-actualization or interracial alliances.

So why did my students turn (back) to whiteness despite their equal access to a massive collection of digitized black discourses? The answer, I submit, lies as much in the timeline I proposed above as it does in the provocations of our seminar assignments, for these apparently inspired them to use the database to (un)learn more about themselves in the context of studying pre-twentieth-century black people and African American matters. In other words, I wonder that their turning to white texts in the database-cum-whiteness inventory did not arise out of an abstract desire—what WRIAS names Disintegration and black identity models name Emersion—to explore the racial antecedents of their diverse contemporary feelings.[4] Throughout the course I had perceived the five white women’s struggle with their roles and identities especially in the time of Ferguson, Baltimore, Cleveland, our own San Antonio, and too many more U.S. cities—and with feelings of both grief and fury about the racialized legacies they have inherited.[5] Equally apparent was the thrilled validation of my students of color. Rather than honing in on white epistemologies for the familiarity of such paradigms (and thereby reifying their supremacy), my students seemed to experience a veritable collective need to examine and critique 19th-century U.S. political, social, philosophical, and economic heteronormativities. Each seemed determined to use Afro-Americana Imprints to try to locate the very moment in whites’ relations with black people in which even white allies (to use today’s parlance) from Harriet Beecher Stowe to Leander Ker to the Presbyterian Church not only accepted but also advanced white supremacy.[6] For as Elizabeth Ammons asserts, “[L]ike almost all other whites at the time, including the overwhelming majority of white abolitionists, the innate characteristics she [Stowe] ascribed to blacks stereotyped and denigrated them while elevating white Anglo Saxons” (9-10).

At some point, we decided that the students’ Readex Report essays would all be structured as lesson plans. Looking back, I think this decision emerged from their palpable desire to think about and correct the limitations of their own respective educations to date, though those have varied greatly, predictably, in accordance with the regions or neighborhoods where they were raised, with their socioeconomic class status as K-12 students, with their religious affiliations or nonconformity, and of course according to their racial identity and sexual orientation. Perhaps we opted for lesson plans because they all envision themselves as educators of one sort or another, and they strive to unlearn now the ignorance they were taught. For unlearning forms a crucial first step on the long road to an internalized self-acceptance despite an inheritance of hate.

Works Cited

Agosto, Vonzell, and Zorka Karanxha. “Resistance Meets Spirituality in the Academy: ‘I Prayed on it!’” The Negro Educational Review 62.1 (2011): 41-66.

Ammons, Elizabeth. “Introduction.” Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin: A Casebook. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. 3-14. Print.

Ariel. “The Negro: What is His Ethnological status?” Ohio: Cincinnati Published for the Proprietor, 1867.

Benezet, A. A caution and warning to Great Britain and her colonies in a short representation of the calamitous state of the enslaved Negroes in the British dominions. Philadelphia: Henry Miller, Printer. 1766.

Cantave, Sophia. “Who Gets to Create the Lasting Images?” The Problem of Black Representation in Uncle Tom's Cabin. Uncle Tom's Cabin: Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Contexts, Criticism. A Norton Critical Edition. 2nd ed. Ed. Elizabeth Ammons. New York: Norton, 2009. 582-595.

DeCuir-Gunby, Jessica T. “A Review of the Racial Identity Development of African American Adolescents: The Role of Education.” Review of Educational Research 20.10 (Winter): 10-20.

DuCille, Ann. Skin Trade. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996. Print.

Dunglison, R. J. Statistics of insanity in the United States. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1860.

Field, Henry M. Bright Skies and Dark Shadows. New York City, 1890.

“Forty-ninth annual report of the Board of Education of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. Presented to the General Assembly, May, 1868.”Philadelphia: 1868. America’s Historical Imprints: Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922: From the Library Company of Philadelphia. Readex, Web. 25 May 2015.

Gladwell, Malcolm. Blink: The Power of Thinking without Thinking. New York: Back Bay Books, 2007. Print.

Helms, Janet E. Black and White Racial Identity: Theory, Research, and Practice. Contributions in Afro-American and African Studies. New York: Greenwood Press, 1990. Print.

Hull, Gloria T., Patricia Bell-Scott, and Barbara Smith, eds. All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women's Studies. Old Westbury, NY: Feminist Press, 1982. Print.

Kerr, Leander. Slavery Consistent with Christianity. Baltimore: Sherwood & Co., 1840.

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press, 1984. Print.

New England Yearly Meeting of Friends. “An Appeal to the Professors of Christianity, in the Southern States and Elsewhere, on the Subject of Slavery: By the Representatives of the Yearly Meeting of Friends for New England.” Rhode Island: Providence, Printed by Knowles and Vose, 1842.

Pence, Ellen. “Racism—A White Issue.” Hull, et al., eds., All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave. 45-47.

Smith, Barbara. “Racism and Women’s Studies.” Hull, et al., eds., All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave. 48-51.

Notes

[1] None of the tragedies I cite appeared on my students’ timelines. However, the lone black student in the course, a practicing social worker completing an MA in Social Work, thematized insurrection in her timeline, in concert with our session on Griggs.

[2] The assigned readings during Spring 2015 included articles by DeCuir-Gunby, Agosto and Karanxha, and excerpts from Blink.

[3] Bales, How to Combat Modern Slavery.

[4] On racial identity formation models, see DeCuir-Gunby 3. See also Helms, passim.

[5] Had there been more time, I would have engaged the seminar in collective discussions of essays about race, gender, and intersectional identities, such as those by DuCille, Lorde, Pence, and Smith.

[6] One team exposed the ambivalence of white heteropatriarchy in the postbellum Presbyterian Church’s investment in black colleges after emancipation. See Forty-ninth annual report of the Board of Education of the Presbyterian Church.”