‘The Right of Revolution Is an Enemy to All Government’: Highlights from The American Civil War Collection, 1860-1922

The November release of The American Civil War Collection, 1860-1922: From the American Antiquarian Society includes a speech on the limitations of citizens to change the federal government, a defense of pacifism, and an abolitionist’s autobiography.

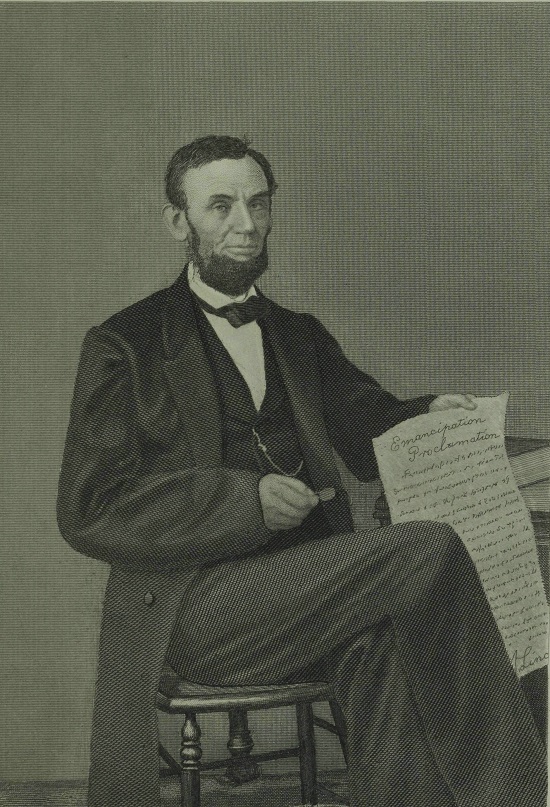

The Rebellion Cannot Abate the State Governments (1862)

Speech of Hon. A.G. Riddle, of Ohio, in the House of Representatives, May 20, 1862

Mr. Speaker, in the wide sea and chaos of blood, tears, and convulsion, the bare, barren, dry land begins to loom up, and the great end to appear. Soon the patient statistician will gather up his facts, and by his tables will show us the exact thousands of lives squandered in this wide waste, and the innumerable millions of substance consumed in the great conflagration. The curious and industrious annalist will swell his huge volumes of the amazing incidents whose frequent recurrence has robbed us of the power of being astonished even. The moralist will go forth in melancholy to mourn the wide-spread licentiousness and demoralization growing out of this huge war, whose irradicable ulcers shall be the last to cicatrize.

Born in Massachusetts, Albert Gallatin Riddle (1816-1902) moved to Ohio where he was admitted to the bar, defended the Oberlin slave rescuers, served in the Ohio House of Representatives, and called the state’s first Free Soil convention. He was later elected as a Republican to the Thirty-seventh Congress during which he spoke in favor of arming slaves. Following his opening remarks describing the waste of war, Riddle turns to the crux of his argument. While he acknowledges that a state’s citizens may change the structure of their state government, Riddle dismisses their right to affect the national government.

But the people of a State cannot, under any circumstances, change the National Government. The people of the whole nation can alone do that. A withdrawal of one or more States is a change of the National Government….The Colonies changed their own Government, but in no way interfered with the home Government of Great Britain. Does the right of revolution in any form exist or find a lurking place in the American system? Do our Governments provide for their own violent dissolution? No. For in all our Constitutions, National and State, the right is in terms repudiated and prohibited by the insertion of provisions prescribing exactly the only way in which this American right of changing a Government can be effected. The loosely admitted heresy of the right of revolution is an enemy to all government. The right of the people to retain and bear arms has reference to no right of revolution in any aspect, and can have none.

The Taking of Human Life Incompatible with Christianity (1864)

By T.F. Tukesbury

In this 32-page pamphlet T.F. Tukesbury interprets the Bible to assert the case for pacifism at all times, including during “the present crisis.”

Is it not true that the Ten Commandments were given to man that he should obey them without exception? Is not every one of them obligatory in every case? Are we to worship the Lord only, without exception?...Are we never to kill? But many are bidding me to stop, saying, “You are carrying things too far;” urging, that “in some extreme cases we may kill, or take the lives of our fellow-men.” But this wicked and fallacious idea is not authorized by God; he has never supplied man with exceptions to this command…

Tukesbury presents a counterpoint allowing for an exception to the prohibition on killing but rejects it because those promoting the position are inconsistent in its application.

It is a very important idea that our opponent should consider that, while he contends for this law of Moses for shedding the blood of the murderer, he has equal authority for parents to have a disobedient son stoned to death. “And they shall say unto the elders of the city, This our son is stubborn and rebellious: he will not obey our voice; he is a glutton, and a drunkard. And all the men of his city shall stone him with stones that he die.” Is our advocate of taking life willing to follow Moses in this? We think he had rather be excused….Also, for gathering sticks on the Sabbath, they were to be put to death: “The man shall surely be put to death; all the congregation shall stone him with stones.” Num. 15:35. Does our opponent wish to hold on to the Mosaic law, and have his friends and neighbors or himself killed for picking up a few sticks?

Tukesbury concedes defensible wars are described in the Bible, but refuses to accept the legitimacy of the Civil War, or that such judgment could be made by man.

But it is said, “Were not some of the wars in the Old Testament times justifiable?” If God directed them they were. If he gave a special command which could not be mistaken, on any particular occasion, it was right to obey it; but this would never allow of a deviation from his established law at any other time. If God saw fit, in the old dispensation, to lay aside any one of his laws for a time being, and direct his people to pursue a different course, he had a right to do so; but the people had no right to select a time themselves. Nor have they at the present day. God has never appeared and spoken to man under the new dispensation in visible form, except in the person of his Son; and when he was on earth, and spoke to man, no direction to smite or kill one another dropped from his lips.

The Life of Cassius Marcellus Clay (1886)

By Cassius Marcellus Clay

Cassius Marcellus Clay (1810-1903) grandly subtitled his autobiography “Memoirs, writings, and speeches, showing his conduct in the overthrow of American slavery, the salvation of the Union, and the restoration of the autonomy of the states.” A notable Kentucky politician, planter, and abolitionist, Clay survived both a duel and an assassination attempt. He describes the latter as beginning with his provocation of a political adversary, Charles A. Wickliffe, by taking

the liberty to interrupt him, and, by his permission, to say: “That hand-bill,” which he had just read, “was proven untrue by another of good authority.” He then would resume his remarks. After this had occurred several times, he sent for Samuel M. Brown, late of New Orleans, who was post-office traveling-agent under Charles A. Wickliffe, his relative, then Postmaster-General under John Tyler. Brown was soon on the ground. He was an old Whig, of social character, strong physique, and, in a word, a political bully….When Mr. Wickliffe repeated the usual rôle, I interrupted him again, as before, saying: “That hand-bill has been proven untrue.” At the moment, Brown gave me the “damned lie,” and struck me simultaneously with his umbrella. I knew the man, and that it meant a death-struggle. I at once drew my Bowie-knife; but, before I could strike, I was seized from behind, and borne by force about fifteen feet from Brown, who, being now armed with a Colt’s revolver, cried: “Clear the way, and let me kill the damned rascal.” The way was speedily cleared, and I stood isolated from the crowd. Now, as Brown had his pistol bearing upon me, I had either to run or advance. So, turning my left side toward him, with my left arm covering it, so as to protect it to that extent, I advanced rapidly on him, knife in hand. Seeing I was coming, he knew very well that nothing but a fatal and sudden shot could save him. So he held his fire; and, taking deliberate aim, just as I was in arm’s reach, he fired at my heart. I came down upon his head with a tremendous blow, which would have split open an ordinary skull….This blow laid his skull open about three inches to the brain…it so stunned him that he was no more able to fire, but feebly attempted to seize me. The conspirators now seized me, and held both arms above my elbow, which only allowed me to strike with the fore-arm, as Brown advanced upon me. I was also struck with hickory sticks and chairs.

After dispatching Brown, Clay writes, “Raising my bloody knife, I said: ‘I repeat that the hand-bill was proven a falsehood; and I stand ready to defend the truth.’” He continues:

But, neither Mr. Wickliffe nor any of the conspirators taking up my challenge, some of my friends, recovering from their lethargy, took me by the arm (seeing where Brown’s bullet had entered,) to the dwelling-house; and, on opening my vest and shirt-bosom, found only a red spot over my heart, but no wound. On examination it was found that the ball, as I pulled up the scabbard of my Bowie-knife, in drawing the blade, had entered the leather near the point, which was lined with silver, and there was lodged. Thus Providence, or fate, reserved me for a better work.

For more information about making The American Civil War Collection available through your library, please contact Readex Marketing.