‘The voice of female sorrow’: Highlights from Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922

The April release of Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922: From the Library Company of Philadelphia includes the first edition of the abolitionist newsletter The Tourist, a two-volume work examining the sinfulness of American slavery, and a collection of letters by and to noted social reformer Abigail Hopper Gibbons.

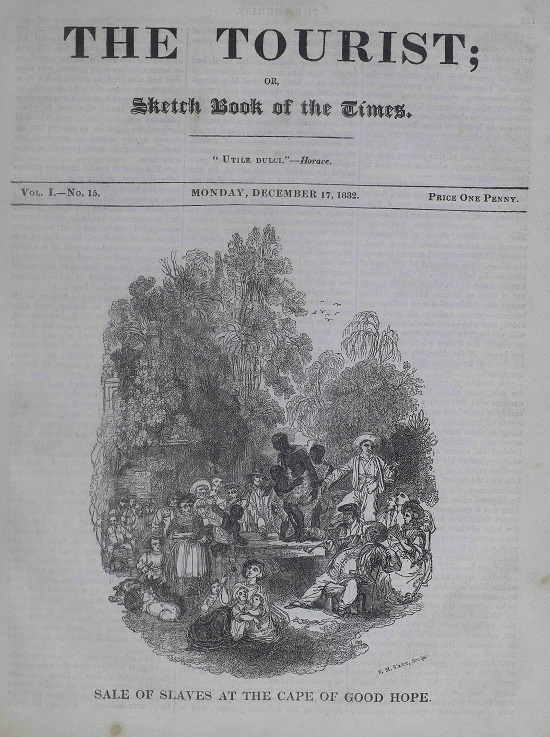

The Tourist; or, Sketch Book of the Times (1832)

Published under the superintendence of the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery Throughout the British Dominions, The Tourist was a literary and anti-slavery journal. It focused upon the exposure of slavery abuses but also contained poetry and essays on religion, housewife duties, and ancient astronomy. The first edition includes this moving account of a white woman attempting to purchase her childhood friend’s freedom:

A few words informed the inquirer that the white person was the daughter of the late farmer, whose effects were now to be disposed of, and that the slave over whom she so affectionately wept was her foster-sister. From her infancy they had been associates—in childhood they were undivided. The distinction which colour made in the eyes of some, to them was not known. The marriage of the farmer’s daughter was the first cause of separation they had ever known, and even then a pain such as sisters only feel at parting was felt by each of them as they said—Farewell! She had retired with her husband to a distant part of the colony, and there received the mournful intelligence of her father’s death, and the account of the public sale of his property; included in this, she was certain, would be found the slave in question: her father’s insolvent circumstances rendered this unavoidable. With an affection which distance, fatigue, and danger could not affect, she had travelled four hundred miles, cheered by the hope of being able to purchase her freedom.

The pleasing delusion which strengthened and encouraged her, during the fatigue of her toilsome journey, fled as she reached the spot where already her beloved foster-sister stood exposed for sale. Here she received the afflictive information that several regular traffickers in human beings were present, who were able and disposed to purchase her at a price much above what she was able to raise. Among this number was one from an adjacent town, who was fully acquainted with her worth, and who had declared his intention to possess her, although a sum should be set upon her head doubling the usual price of an ordinary slave.

The voice of female sorrow is powerfully eloquent, and is ever sufficient to move the heart with pity and commiseration, excepting the hearts of villains and cowards.

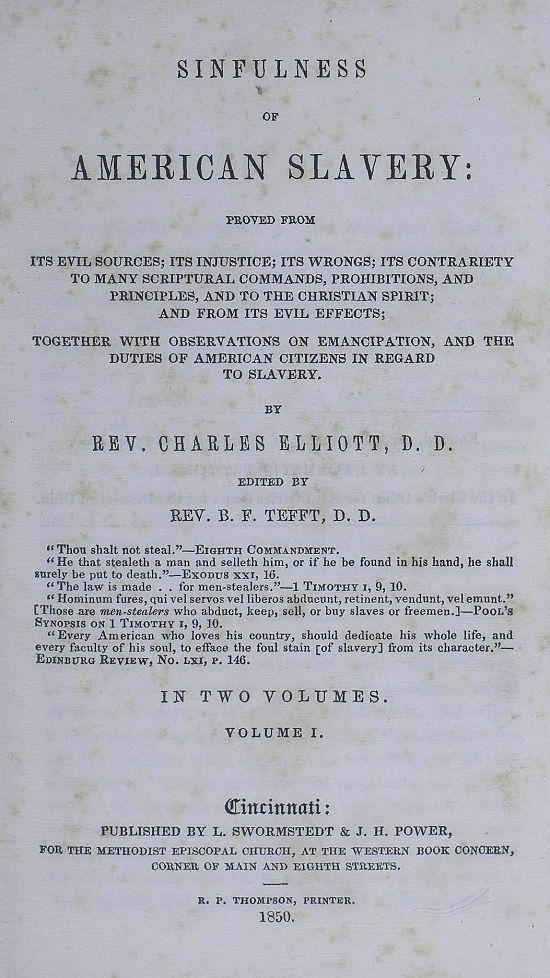

Sinfulness of American Slavery (1850)

By Rev. Charles Elliott, D.D.

Charles Elliott (1792-1869) emigrated from Ireland in 1816 with his widowed mother and her other eight children. He became a writer on Methodism and was the first editor of the Pittsburgh Christian Advocate. In this work on American slavery, Elliott describes its “evil sources; its injustice; its wrongs; its contrariety to many scriptural commands, prohibitions, and principles, and to the Christian spirit; and from its evil effects; together with observations on emancipation, and the duties of American citizens in regard to slavery.”

Rev. Charles Elliott begins his treatise by defining a slave as

a person divested of the ownership of himself, and conveyed, with all his powers of body and mind, to the proprietorship of another.

He continues his introduction, writing:

There are but two slaveholding powers in all countries where slavery exists by law—the master and the government. A slaveholding government is one which authorizes individuals to deprive their fellow-men of self-ownership. An individual slaveholder is one who subjects men to the laws of slavery, or who voluntarily holds slaves by law.

Elliott goes on to compare the American system with that of the Romans, arguing:

But American slavery is best defined by quoting the laws which authorize and protect the system. In the civil or Roman laws, slaves were held “pro nullis; pro mortuis; pro quadrupedibus”—“as nothing; as dead; as quadrupeds.”

The condition of slaves, in our slaveholding states, is little different or better, as far as laws are concerned, than under the Roman laws. According to the laws of Louisiana, “a slave is one who is in the power of a master to whom he belongs. The master may sell him, dispose of his person, his industry, and his labor: he can do nothing, possess nothing, nor acquire any thing but what must belong to his master.”—Civil code, art. 35. There is, indeed, in theory, a limitation to the master’s power in punishing the slave, yet no such limitation practically exists, or can, by law, be enforced. “The slave is entirely subject to the will of his master, who may correct or chastise him, though not with unusual rigor or loss of life, or to cause death.” Art. 173.

Life of Abby Hopper Gibbons (1896)

Edited by Sarah Hopper Emerson

Born in Philadelphia, Abigail Hopper Gibbons (1801-1893) was an abolitionist, social welfare activist, and schoolteacher. This biography based upon her letters includes one written by her daughter Lucy who describes the family’s home being sacked by anti-abolitionists during the New York City draft riots of 1863.

You know what happened after the riot began. Our neighbors behaved nobly. Judge Robinson entered with the mob and saved what he could—a portrait of Willie a drawer full of letters, and a few books &c. Another, Mr. Horn, stood in the parlor and threatened the mob with a pistol. He drove off the women (!!!) who were trying to set fire to the house with torches, but was finally obliged to retreat through the back window. Mr. Grey rescued a sheet full of wet clothes which were being carried off; and his wife had them re-washed and ironed. A little boy from somewhere, only about twelve years old, helped like a little soldier, bringing buckets of water to put out the fire. A Mr. Thompson behaved beautifully. The people in the house back of us pointed out to the police and military the thieves who were trying to escape through the back yards. A strange young man saved some things. Another came last night to tell us where we could find a chair which we valued. Our butcher went into the midst of the mob, and declared he would not have that house touched,—for which he was badly beaten, but will recover.

For more information about Afro-Americana Imprints, 1535-1922: From the Library Company of Philadelphia, or to request a trial for your institution, please contact Readex Marketing.