‘I Am by Nature, Education, and Religion a Yankee-Hater’: Highlights from The American Civil War Collection, 1860-1922

The August release of The American Civil War Collection, 1860-1922, includes a pictorial of a dramatic naval engagement, an argument against an eventual reconciliation between the North and South, and the memorial of General Francis C. Barlow.

The Privateer’s Fate (1861)

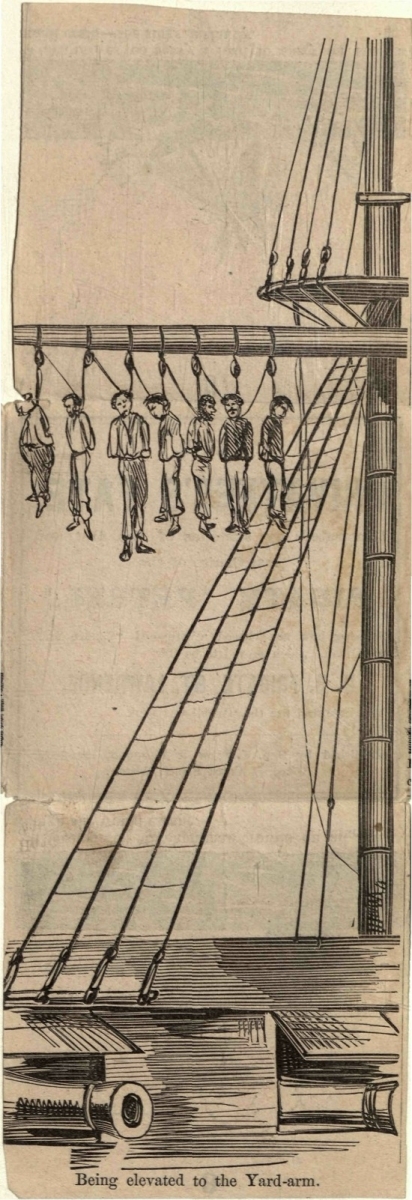

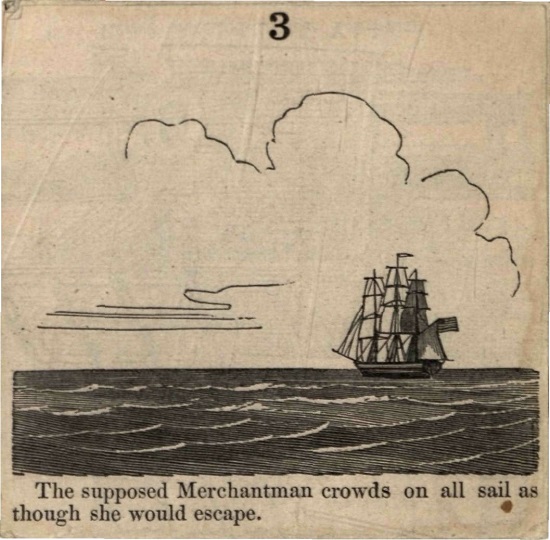

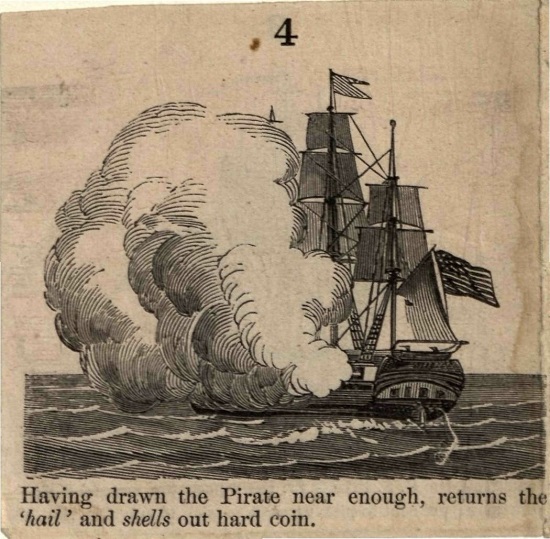

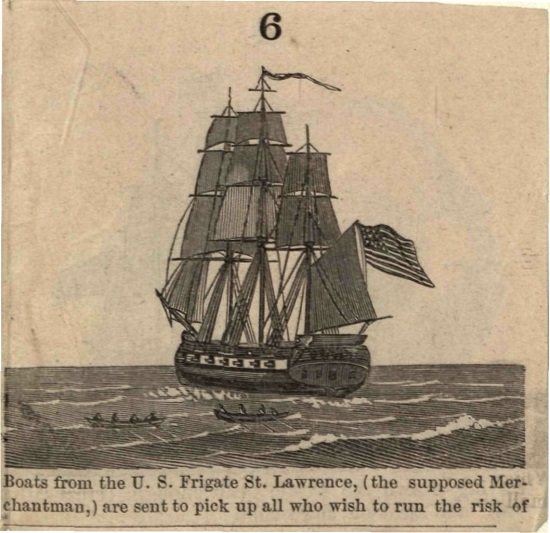

The first and last cruise of the pirate, or privateer, Petrol is recorded in this series of sketches. This recording suggests the Petrol mistook the USS St. Lawrence for a merchant ship and was sunk after a failed attack.

Other accounts of this naval encounter tell of the Petrel, sailing under the British colors, being pursued for several hours before being overhauled by the St. Lawrence. The Petrel then ran up the Confederate colors and after an exchange of fire was hit in the bow and sunk. Thirty-eight sailors were rescued and transported north aboard the USS Flag. Although the present account depicts a rescue there is no reference to the Flag; instead it tells of a more immediate judgment passed against the rescued sailors—as seen in the uppermost image.

Military Despotism (1863)

Douglas M. Hamilton, “a politician of some note in Louisiana,” wrote a letter to editor of the Jackson Mississippian in response to an article suggesting free states of the old Union could be admitted into the Confederacy. Hamilton felt this was a bridge to far, writing:

We can offer to join them, if necessary, in a war against Lincoln, Abolition, and New England Yankees, and after catching and putting to death every public man in the old Union who has been a counsellor or advisor of Lincoln, we can make a treaty of peace and commerce with them, granting them the free navigation of the Mississippi river to its mouth, (a right we never denied them, however,) and moderate privileges of trade with us. But farther than this I would not go, and I hope you would not either.

He continues, arguing against a reconciliation with the North:

I am by nature, education, and religion a Yankee-hater. I loathed the old Union, and no act of any people ever afforded me half the delight that the secession of the slave States from the old Union did. You may imagine, therefore, my chagrin and surprise when I notice in the columns of a leading paper, in one of the leading secession States, articles advocating a reconstruction of the Union. And this at the very crisis of revolution, when our independence, which we have suffered so much for, and fought so gloriously for, is within our grasp, and foreign nations, as well as Yankeedom, are on the point of acknowledging it.

My dear sirs, write to me in reply, and say that you are not in earnest, but are baiting traps to catch green Western Hoosiers. You cannot surely be planning to permit these vermin, uncouth, fanatical, and depraved, as they have proved themselves to be, to enter again our legislative halls, divide our offices of profit and trust, and partake freely of all privileges of our own citizens, of voting, owning property, etc., etc.? You must have learned by the experience of the political agitations of the past twenty-five years, accompanied by hatred, abuse, and jealousy, followed by a war characterized by more outrages, plunderings, burnings, cruelties, indignities, and bloodshed than any on record, that our civilization is too distinct, our instincts too diverse, our manners, habits, thoughts, occupations, and interests too widely different, ever to permit us to live together again under the same government, with the same laws and lawmakers, and the same men to share in making and executing their laws, and administering this government.

Francis Channing Barlow (1896)

By Edwin Hale Abbot

Barlow biographer Edwin Hale Abbot (1834-1927) served in Boston as an attorney for the Alabama Claims—the U.S government’s demands for damages caused by British-built Confederate warships—before becoming president of the Wisconsin Central Railway. In his biography of the Union General, Abbot quotes Nelson A. Miles, a general who served under Barlow. Miles describes Barlow’s regiment’s first encounter with the Confederate Army in the days after the Battle of Seven Pines, writing:

At this time the regiment had not been ‘fire-tried,’ and of course there was more consternation in preparing for the first conflict than on subsequent occasions. He, however, deliberately formed his regiment in line of battle, took especial care to see that every officer and non-commissioned officer and soldier was in his correct position, and then, taking his place in rear of the centre and close to the colors of the regiment, he addressed a few words to his command, which were simply the announcement that in a few moments the advance of the enemy would reach their line, and an engagement would be fought. He did not hesitate fully to impress upon the minds of those under command the fact that a serious encounter would occur, and also that he expected every man to stand in his place and fulfil his duty to the utmost with faithful fortitude. Having said these few words of warning, encouragement, and admonition, he drew his sword, and closed his remarks by saying that the first man who left his place and attempted to retreat from the presence of the enemy would receive his swift administration of subjugative discipline. His language may not have been clothed in those exact words, but they were so forcible, and so strongly had he impressed his character and discipline upon the regiment, that every man knew what he might expect if he undertook to play the role of a coward, and they felt a consciousness that it would be quite as safe to take the risk of the enemy’s fire as to encounter the vengeance of his sword. There appears, however, to have been no disposition to take a backward step. The regiment received the onslaught of the victorious and exultant host as the granite wall receives the rush of the tidal wave, with a solidarity and strength that hurled it back broken, crippled, and defeated. Although the regiment lost severely in killed and wounded, including the gallant lieutenant-colonel, yet they all fell in line as correctly in position as if they had been formed for parade, and the ground in front of the regiment was thickly strewn with the bodies of the brave enemy. The rebel force, however, was defeated, and from a strong defense the regiment quickly assumed the offensive, and, making a countercharge, swept the enemy from the field, and formed a part of the line that drove them back in disorder.

For more information about The American Civil War Collection, please contact Readex Marketing.