‘They Should Be Removed and All United’: Highlights from Territorial Papers of the United States

The January release of Territorial Papers of the Unites States, 1765-1953, includes Congressional Legislative Reports on the relocation of American Indian tribes, including the Winnebago, now recognized as the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin. Also available this month are Territorial Legislative Reports from Alaska. Among the many topics covered are the establishment of Alaska's Pioneer Home system, the fear of sedition during World War I, and much more.

28th Congress 1st Session; Bills, Resolutions, Reports, and Related Documents, December 18, 1843-June 11, 1844

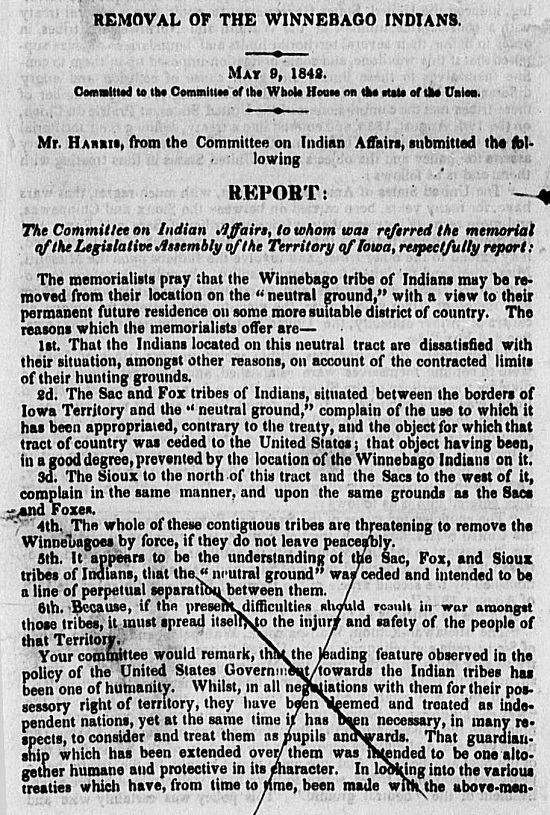

Among the many territorial issues before the 28th Congress was the subject of removing and relocating American Indians. The cascading effect of this ill-conceived policy is illustrated in a document focusing on the Territory of Iowa. On May 9, 1842, Virginia congressman William Alexander Harris (1805-1864) “from the Committee on Indian Affairs, submitted the following report: The Committee on Indian Affairs, to whom was referred the memorial of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Iowa, respectfully report: The memorialists pray that the Winnebago tribe of Indians may be removed from their location on the ‘neutral ground,’ with a view to their permanent future residence on some more suitable district of country.”

Providing background in support of their request, the memorialists (that is, the petitioners) cite the First Treaty of Prairie du Chien, which was signed by William Clark and Lewis Cass and representatives of the Sioux, Sac and Fox, Menominee, Iowas, Winnebago, and Anishinaabeg on August 19, 1825. The treaty’s preamble stated:

The United States of America have seen, with much regret, that wars have, for many years, been carried on between the Sioux and Chippewas, and more recently between the confederated tribes of Sacs and Foxes and the Sioux, and also between the Iowas and Sioux, which, if not terminated, may extend to the other tribes, and involve the Indians upon the Missouri, Mississippi, and the lakes, in general hostility. In order, therefore, to promote peace among these tribes, and to establish boundaries among them and the other tribes who live in the vicinity, and thereby to remove all causes of further difficulty, the United States have invited…

Citing an additional treaty signed five years later and clarifying the previously established boundaries, the petitioners identify the source of the current dilemma:

And thus was established what was known, then and since, as the “NEUTRAL GROUND,” being a tract of country forty miles wide, and running from the Mississippi to the Des Moines river, a distance of some 160 miles or more, and entirely separating the territory of the Sioux from that of the Sacs and Foxes. And the main object sought by the treaty, being peace between these tribes, seems to have been well attained by the establishment of the “neutral ground.” This policy was certainly wise and humane; and there is no reason to doubt its entire success, had not the United States Government itself, in placing a strange tribe upon this neutral tract, and in such a relation to the tribes north and south of it as to be a perpetual cause of irritation and dislike.

In 1832, at the conclusion of the Black Hawk War, the United States had signed a treaty which ceded a large portion of the neutral ground to the Winnebago, the aforementioned “strange tribe.” Just less than two years after reporting the memorial, on March 27, 1844, the Committee on Indian Affairs reported H.R. 18 resolving

That the President of the United States be requested to cause to be selected a permanent home for the said Winnebago tribe of Indians, which shall be assigned to them in consideration of their right to hunt upon the western part of what is termed the neutral ground; and the agent appointed for the purpose aforesaid shall be entitled to receive not exceeding five dollars per day for his services.

Two months later on May 29, 1844, the Committee on Indian Affairs submitted another report to Congress. This time relocating “the Pottawatomie and other Indians” who, unlike the Winnebago, seemed to occupy too much land. So much, in fact, it was causing a hardship on the government’s ability to meet their treaty obligations.

By the treaty of September, 1833, made with the united band of Pottawatomie, Chippewas, and Ottowa Indians, (2d article) the United States granted to them five millions of acres of land on the Missouri river, immediately north of the State of Missouri; which grant of land was intended for their future place of abode, at the time the treaty was made and concluded.

At present, about one-half of the united band of said Indians reside on said tract of land, and the remainder reside on the Osage river, south of the State of Missouri. These Indians, under various treaties made with the United States, are receiving a very large annuity—a fund sufficient, if they could all be united, to render their condition comfortable. But as they reside in different places, it seems impossible for the Government to comply with the conditions and terms of the treaties made with them. Hence the great necessity, not only for the welfare and prosperity of the Indians, but fully to enable the Government to carry into effect the stipulations of the treaties made with them, that they should be removed and all united.

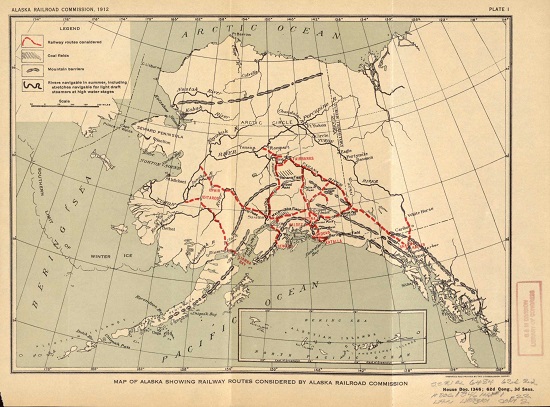

1915 Session; Texts of Senate Bills

Alaska became a U.S. territory in 1912. The 1915 Session of the Alaskan Senate saw a diverse assortment of bills presented to the legislature ranging from the regulation of hunting, fishing, and the fur trade, to voter registration, to the extension of telegraph lines to remote areas. Legislation establishing a rudimentary social safety net, criminalizing carnal acts, and preventing political dirty tricks was also offered.

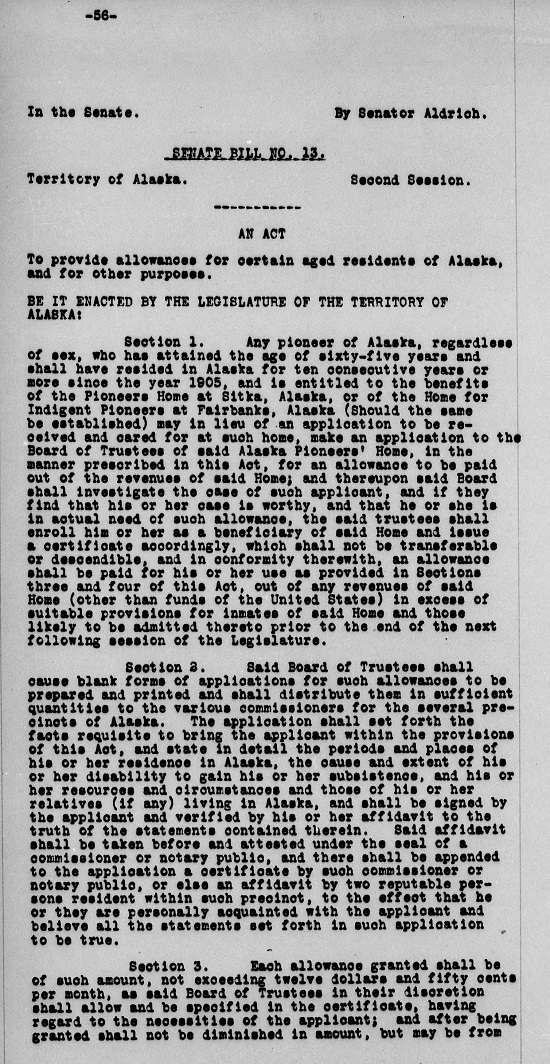

Senate Bill No. 13, an Act to Provide Allowance for Certain Aged Residents of Alaska, and for Other Purposes, begins:

Any pioneer of Alaska, regardless of sex, who has attained the age of sixty-five years and shall have resided in Alaska for ten consecutive years or more since the year 1905, and is entitled to the benefits of the Pioneers Home at Sitka, Alaska, or of the Home for Indigent Pioneers at Fairbanks, Alaska (Should the same be established) may in lieu of an application to be received and cared for at such home, make an application to the Board of Trustees of said Alaska Pioneers’ Home, in the manner prescribed in this Act, for an allowance to be paid out of the revenues of said Home; and thereupon said Board shall investigate the case of such applicant, and if they find that his or her case is worthy, and that he or she is in actual need of such allowance, the said trustees shall enroll him or her as a beneficiary of said Home and issue a certificate accordingly, which shall not be transferable or descendible, and in conformity therewith, an allowance shall be paid for his or her use as provided in Sections three and four of this Act, out of any revenues of said Home (other than funds of the United States) in excess of suitable provisions for inmates of said Home and those likely to be admitted thereto prior to the end of the next following session of the Legislature.

Later that April Senate Bill No. 49, an “Act to Protect Political Enclaves and Conventions against Imposters and the Use of Fraudulent Credentials by Delegates and Representatives,” also passed. For researchers seeking information about political shenanigans and their prevention in the U.S. territories, Bill No. 49 is an interesting place to start.

1917 Session; Texts of House Bills

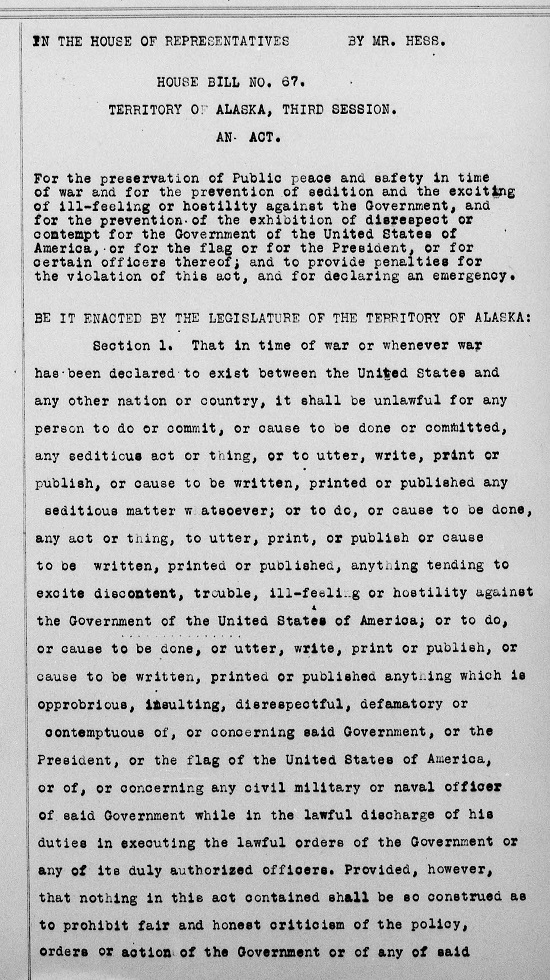

The 1917 Session of the Alaskan House of Representatives included bills to regulate expanding mining operations, “for the erection of cabins and shelter along traveled roads and trails,” and requiring emergency accommodations for dog teams. Perhaps surprising is House Bill No. 39 which placed “a bounty on eagles and providing for the payment of the same.” Taking place during World War I, this legislative session also saw House Bill No. 67 which sought to restrict free speech rights:

That in time of war or whenever war has been declared to exist between the United States and any other nation or country, it shall be unlawful for any person to do or commit, or cause to be done or committed, any seditious act or thing, or to utter, write, print or publish, or cause to be written, printed or published any seditious matter whatsoever; or to do, or cause to be done, any act or thing, to utter, print, or publish or cause to be written, printed or published, anything tending to excite discontent, trouble, ill-feeling or hostility against the Government of the United States of America; or to do, or cause to be done, or utter, write, print or publish, or cause to be written, printed or published anything which is opprobrious, insulting, disrespectful, defamatory or contemptuous of, or concerning said Government, or the President, or the flag of the United States of America, or of, or concerning any civil military or naval officer of said Government while in the lawful discharge of his duties in executing the lawful orders of the Government or any of its duly authorized officers.

For more information about this digital collection, including ways to help bring access to your institution, please contact Readex Marketing.