“The best presentation at this year’s ALA”: Librarians praise Readex-sponsored talk by Yale’s Joanne B. Freeman

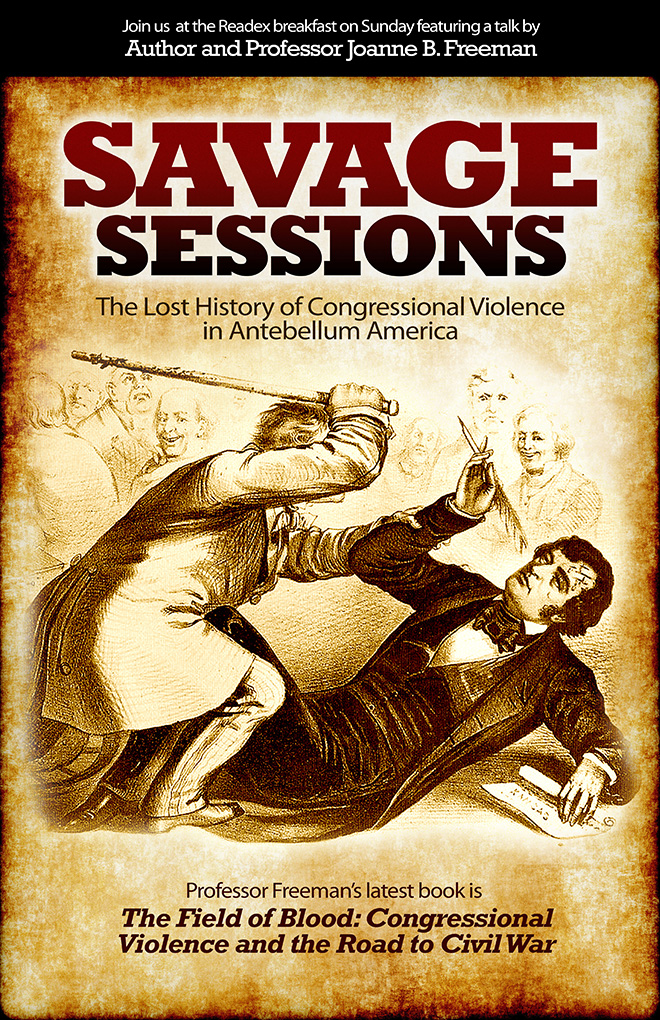

For more than a decade Readex has brought acclaimed historians to speak about their scholarly work to the sharp and curious membership of the American Library Association. At the ALA Annual Conference in Washington, D.C., last month, Joanne B. Freeman, Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University, presented “Savage Sessions: The Lost History of Congressional Violence in Antebellum America.”

Freeman shared evidence of more than 70 incidents in the United States House of Representatives and Senate of mortal threats, canings, fist fights and even a duel. In a post-event survey, participants offered their reactions:

Dr. Freeman was a fantastic speaker. She was engaging, she was insightful.

Best presentation yet! Wonderful speaker, timely topic.

Great! Informative & entertaining.

Presentation brought history to life!

The best presentation at this year’s ALA. Dr. Freeman’s depth of knowledge was stunning.

In her fascinating talk, Freeman described the events leading up to the Brooks-Sumner Affair, which occurred on May 22, 1856. While it may be the most well-known act of Congressional violence, it was far from the only incident. See the full presentation.

So, why hasn’t the story of congressional violence been more fully told before?

According to Freeman, who spent 17 years steeped in primary sources while researching and writing The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War, the evidence is extremely hard to find. “If you’re not looking for it, you won’t see it,” she said. Most of the violence was censored out of newspapers which were the period’s equivalent of the Congressional record—The Congressional Globe and the National Intelligencer. There are, however, clues.

The limited number of published accounts of violence are also a result of the nature of the Washington press at the time. In the 1830s, the local press corps consisted of a handful of men working for a handful of local Washington newspapers. After observing congressional proceedings, reporters verified their notes with the congressmen who had been speaking before their stories went to publication.

According to Freeman, the Washington press had many reasons to smooth over the rough edges of what happened:

“The newspapers that these reporters worked for were unquestionably partisan. Objective news is not on the radar screen at this point…As a reporter, it was in your interest to make your party’s congressmen look good. It was also in your interest as a reporter to make congressmen look good because Congress granted government printing contracts, and most newspapers relied on those contracts for survival. Plus, unhappy congressmen occasionally slugged the reporter who made them unhappy.”

Freeman spent a year reading the record to understand the culture of Congress and evaluate interactions between representatives. She learned about “the pacing of debate, the way people treated each other, the things that set people off, the things that didn’t set people off but by modern standards seemingly should have.” For Freeman, the record was invaluable in building her understanding of the time and identifying instances of violence. Personal correspondence and newspapers—particularly databases of newspapers—were also critical to her research.

This combination of documents enabled Freeman to begin to see patterns. For example, she was able to identify that the House was more physically violent, while the Senate tended toward duels. There were also indications of divided ranks in Congress with “fighting men”—typically Southern, armed, and willing to fight—and “non-combatants” of the North. There was a pattern of Southerners bullying Northerners to protect the institution of slavery. “For a time, this strategy worked quite well,” Freeman said, and fighting men from the South tended to get re-elected.

But by the 1850s, things began to change. With each new state admitted to the Union, the debate over whether it would be free or slave intensified. The telegraph also instigated change, as it sped up communication. Reporters could no longer spin as easily what had happened on the floor of Congress. More than a 150 years later, the speed of communication has only increased, with social media serving as a direct line between lawmakers and constituents, influencing how Americans view what happens on the floors of Congress. While contentious debate once again inches toward fever pitch in congressional chambers, it is far from “The Field of Blood” that led up to the Civil War.

We hope to see you at a future Readex breakfast event! Please let your Readex account executive know you would like to receive an invitation.

To watch previous ALA breakfast presentations hosted by Readex, visit our Event Talks.