“The Drama Is—Rubbish”: The Early Impact of ‘The Black Crook,’ the Shocking and Scandalous American Musical

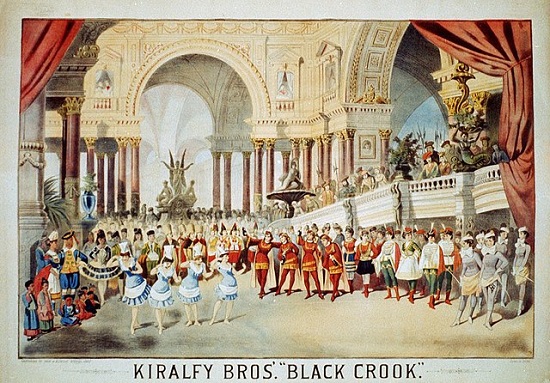

“The Black Crook”—the progenitor of spectacular theater in the United States—opened at Niblo’s Garden, a 3,000-seat New York City playhouse, on September 12, 1866. Whether this American musical can be called the country’s first, “The Black Crook” had an immense impact on the future of popular entertainment in the U.S. Its initial production ran for nearly 500 performances and created a nationwide mania, stimulated by the clergy who railed against its abundant display of female pulchritude.

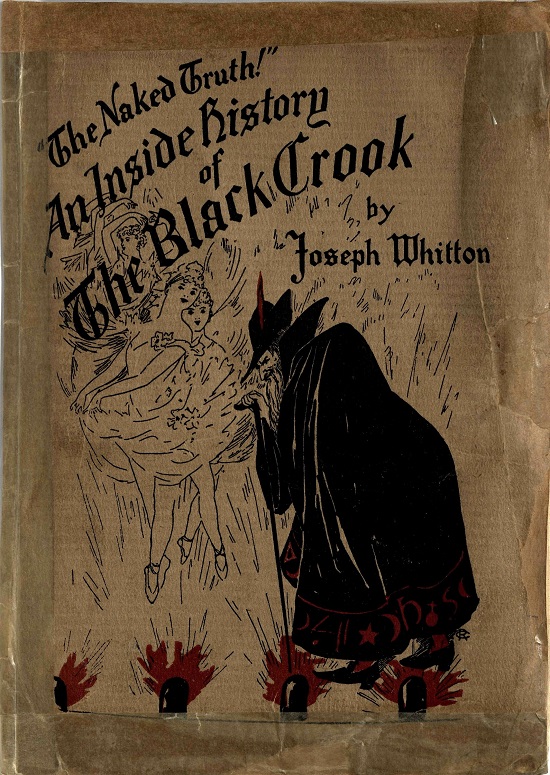

In his preface to “The Naked Truth!”: An Inside History of The Black Crook (1897), digitized from the holdings of the New-York Historical Society and found in American Pamphlets, Joseph Whitton wrote:

It is curious that the history of the Black Crook—the pioneer of the American Spectacular Drama, and greater in tinseled gorgeousness and money-drawing power than any of its followers—should never have been told, or, rather, truthfully told.

Whitton by his own account had a “connection with the financial department of Niblo’s Garden, previous to the production and during the run of the Crook,” which “enables him to know the facts…”

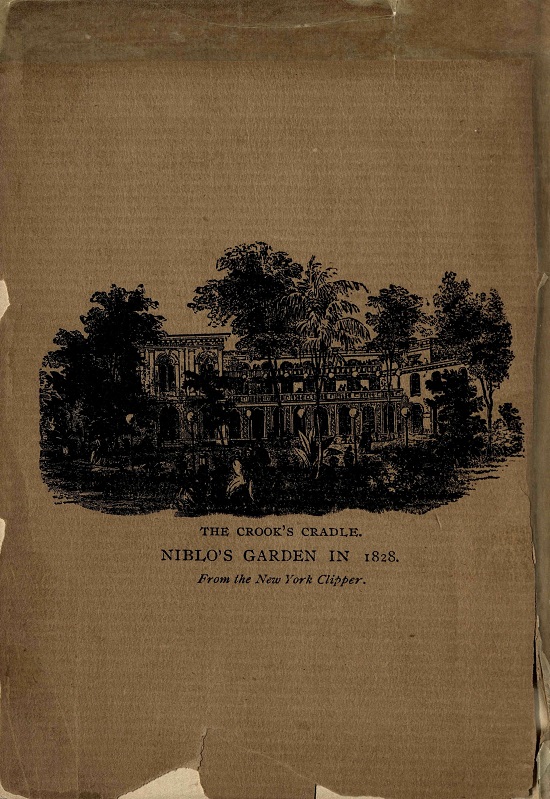

In this pamphlet, he describes Niblo’s as “then considered the most popular of New York’s theaters, and not—what in after years it became—too far down town for the convenience of amusement-seekers.” His excellent and personal account of the story of the 1866 opening of “The Black Crook” serves as a reference for myriad newspaper accounts that recorded the phenomenon of this spectacular show. He also is adroit at exposing many aspects of New York City’s theater world in the latter part of the nineteenth century. It was a cutthroat environment, highly competitive, and graft was common.

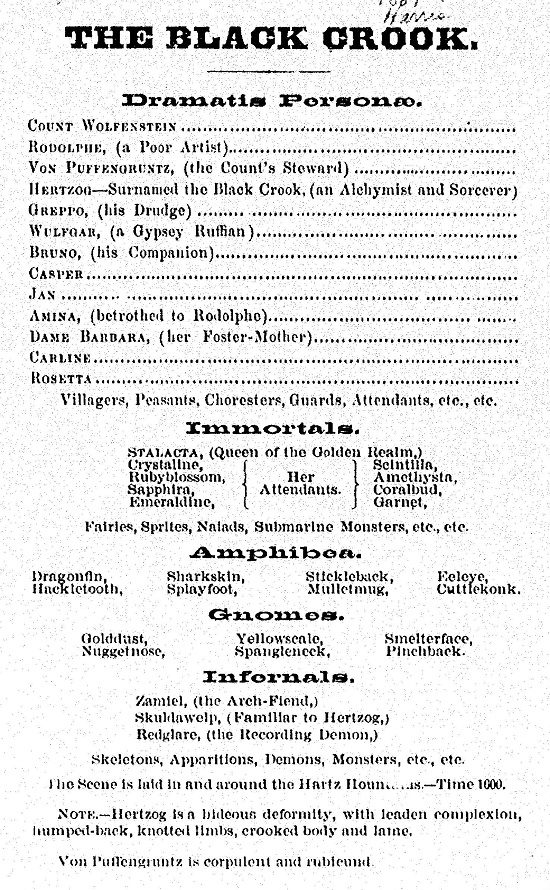

The full script of the spectacle can be found in Nineteenth-Century American Drama: Popular Culture and Entertainment, 1820-1900. The edition below was printed in 1867, shortly after "the original magical and spectacular drama" opened at Niblo's.

From the same early printing of the script, here's the cast of characters, including “Hertzog—Surnamed the Black Crook, (an Alchymist and Sorcerer)."

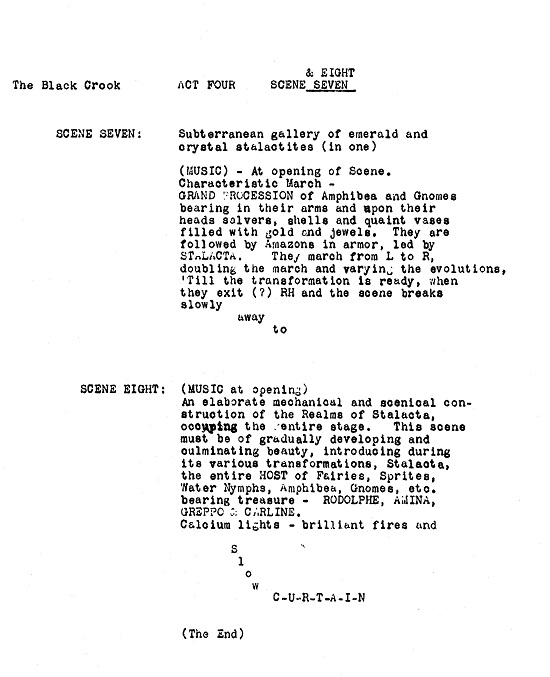

From a later edition of the script, published in 1899 and also found in Nineteenth-Century American Drama, here's how this early extravaganza ends:

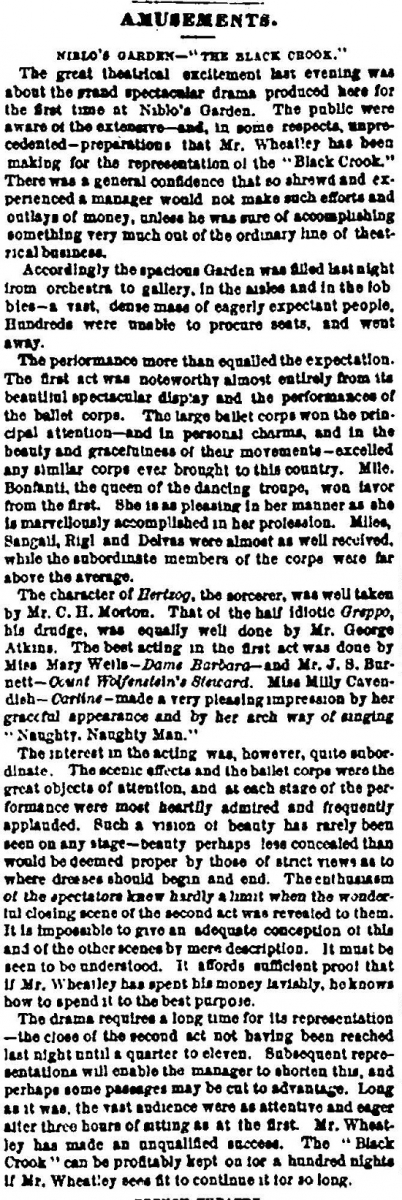

The first reference to “The Black Crook” in Early American Newspapers is found in the New York Evening Post and is dated September 13, 1866—the day after the show opened. It reads in part: “The great theatrical excitement last evening was about the grand spectacular drama produced here for the first time at Niblo’s Garden.” Because the production was undertaken by William Wheatley,

There was a general confidence that so shrewd and experienced a manager would not make such efforts and outlays of money, unless he was sure of accomplishing something very much out of the ordinary line of theatrical business.

Accordingly the spacious Garden was filled last night from orchestra to gallery, in the aisles and in the lobbies—a vast, dense mass of eagerly expectant people. Hundreds were unable to procure seats, and went away.

The article includes an enthusiastic review, which begins, “The performance more than equaled the expectation."

The New York Tribune was a dedicated competitor of the Evening Post. On September 17, 1866, the Tribune published its review which set the tone for scores of subsequent reviews in papers all over the nation when franchised productions arrived in their cities. After writing that, “The scenery is magnificent; the ballet is beautiful; the drama is—rubbish,” the reviewer begins his comments on the ticket buyers this way:

The first notice of an out-of-town production indicates how rapidly the producers began to franchise performances. It is from the Jackson (Michigan) Citizen Patriot on October 12,1866, less than a month after the show opened in New York City. It reads in full “The Black Crook is meeting with great success at Buffalo, and is destined to have a long run.”

The early evidence of enthusiasm for the show in the press was stimulated by those who spoke or wrote publicly condemning it. It seemed the more they brought down brimstone the more excited people became to see it for themselves. The first and more influential of these was a Dr. Charles B. Smyth, “the reformer of the clergy and severe pulpit critic of theatrical immoralities,” whose lecture to a large audience was reported enthusiastically by the New York Herald on November 27, 1866:

The object of Dr. Smyth’s discourses is to expose, and, if possible, put down, one of the grossest immoral productions that ever was put upon the stage. Men go to see it, but they leave the theatre worse in morals than when they entered it.

This is a mere taste of how the show was condemned. The cause of this was essentially the female dancers in the ballet whose gauzy legs were exposed, and who had been specifically selected and imported from decadent France. Dr. Smyth titled his presentation “The nuisances of New York, particularly the naked truth.”

In response to the moral condemnation, much of the press took a wry attitude. The Cincinnati Daily Enquirer reported on November 14, 1866:

The New York Herald, having asserted that there are fifty men to one woman that attend the performance of the Black Crook at Niblo’s, a careful count was kept at the doors of the establishment, one night recently, and, when the audience was all in, it was found to number 1,618 men and 1,045 women.”

On December 4, 1866, the Richmond (Virginia) Whig published an excerpt from a letter to the editor which read in part:

The Black Crook is simply a very French ballet. Thirty or forty young women, of fine physique, and dressed in low neck and bare arms, with very short skirts and flesh-colored stockings, which reach very high up….He [Reverend Smythe] has heard a good deal about the Black Crook; so he went to Niblo’s to see for himself. What he saw there no one knows. He saw so many things that nobody else sees, that I am satisfied that for the time being he labored under a fit of hallucination, a temporary madness occasioned by the temptation to which he was subjected.

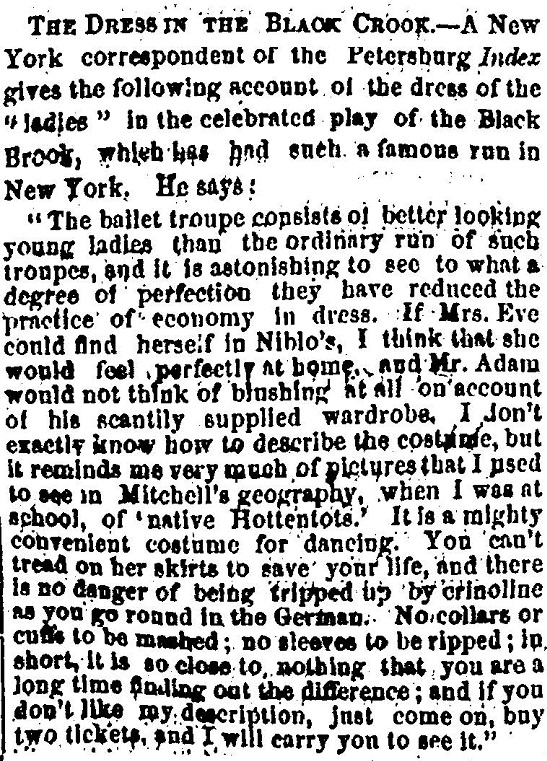

In another review—this one published in the Daily Constitutionalist of Augusta, Georgia, on February 2, 1867—the correspondent jests that

If Mrs. Eve could find herself at Niblo’s, I think that she would feel perfectly at home….I don’t exactly know how to describe the costume, but it reminds me very much of pictures I used to see in Mitchell’s geography, when I was at school, of ‘native Hottentots.’ It is a mighty convenient costume for dancing….No collars or cuffs to be mashed; no sleeves to be ripped; in short, it is so close to nothing that you are a long time finding out the difference; and if you don’t like my description, just come on, buy two tickets, and I will carry you to see it.

There were examples of nineteenth-century snark such as this from the Memphis Daily Avalanche on February 16, 1867:

One evening, it is true, Niblo’s was shut, but not for lack of an audience, or by any order of the authorities. [The female stars of the ballet] were wanted by a celebrated millionaire for his own private theater, and were let out by the proprietor for the night to the owner of the finest mansion on Fifth avenue where the great world of that fashionable quarter were invited to applaud the unrestricted postures and gambols of the celebrated troupe.

Soon a joke popped up and was repeated in quite a few newspapers. From the Trenton State Gazette on January 14, 1867:

Several of our citizens have been to New York to see the “Black Crook.” One of them says he is convinced of the folly of women spending money for so much dress, when they can render themselves so fascinating with very little.

Other jokes followed, such as this one from the Owyhee Avalanche of Silver City, Idaho, on August 10, 1867: “Gris, the ‘Fat contributor,’ says he was asked to write a ‘take off’ on the ‘Black Crook.’ He replied that he couldn’t see anything to take off.”

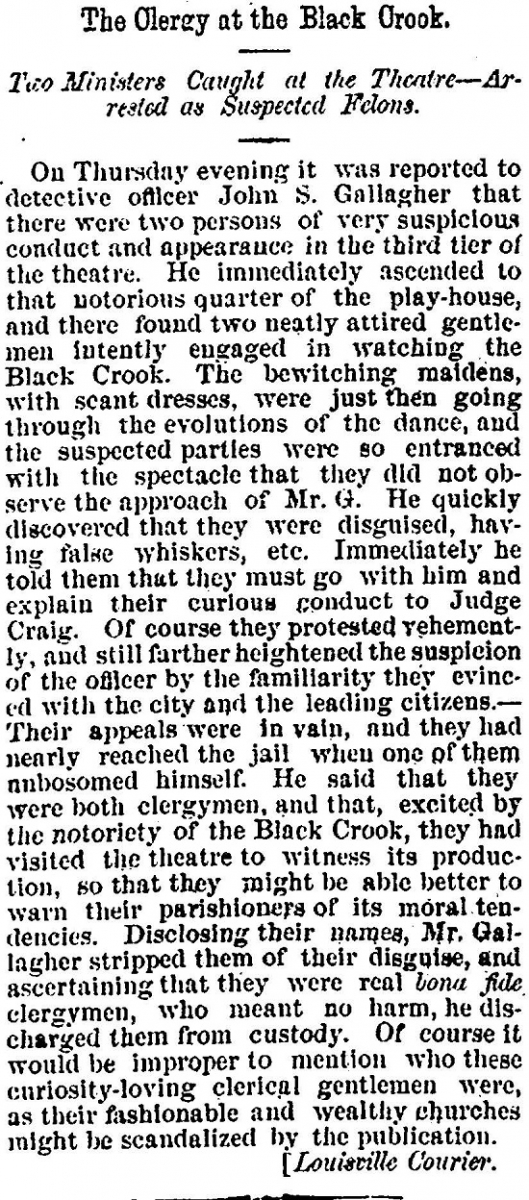

The newspaper coverage, along with the denunciations of the play by Reverend Smythe and other clergy members, only flamed the interest of the public to see “The Black Crook” for themselves. Speaking of the reverend, on October 4, 1867, the Daily Constitutionalist of Augusta, Georgia, reprinted an article from the Louisville Courier relating to the arrest of two ministers at a performance who were disguised in false beards. They were being hauled off to a judge when one of the clerics that they had been so “excited by the notoriety of the Black Crook, they had visited the theatre to witness its production, so that they might be able better to warn their parishioners of its moral tendencies.”

The crowds continued to swell as contract performances opened in many American cities. Papers from New England to the western territories including the Plain Dealer (Cleveland) and the Daily Eastern Argus (Portland, Maine) described the frenzy at the performances in their cities. The Memphis Daily Avalanche noted that “General Grant went to see the Black Crook and also went behind the scenes.”

It was only in Philadelphia that the crowds stayed away. The New Orleans Daily Picayune reported on September 14, 1867, that “The “Black Crook” is a failure in Philadelphia. In view of the well-known morality of that city, this may be regarded as a leg-itimate failure.”

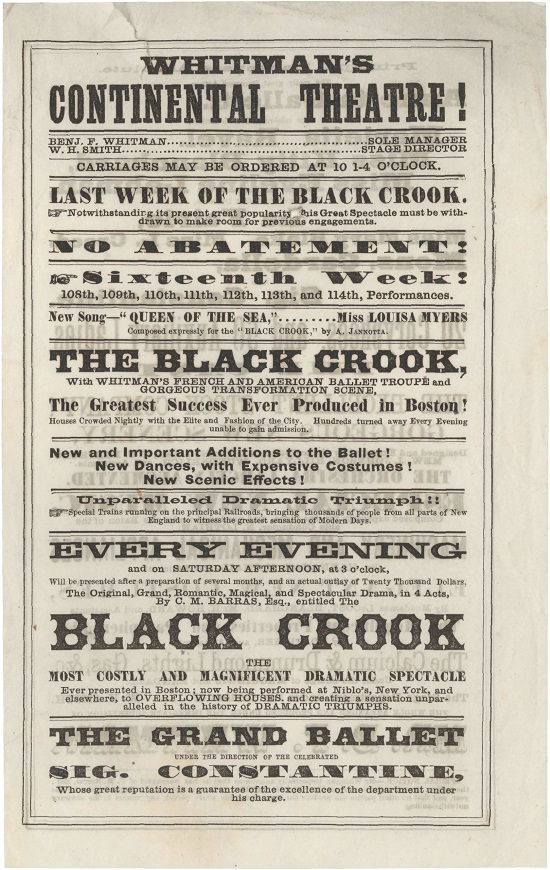

For insight into how “The “Black Crook” was promoted, we can find in American Broadsides and Ephemera this 1866 playbill from Whitman’s Continental Theatre in Massachusetts:

The Greatest Success Ever Produced in Boston!

Unparalled Dramatic Triumph!!

The Original, Grand, Romantic, Magical and Spectacular Drama, in 4 Acts

The Most Costly and Magnificent Dramatic Spectacle

And finally, also found in American Broadsides and Ephemera, is this 1866 songsheet of the play's hit You Naughty, Naughty Men “as sung by Miss Millie Cavendish in the ‘Black Crook’ at Niblo’s Garden.”

In this post, four Readex products were used to explore the extraordinary impact of “The Black Crook” in the nineteenth-century United States: American Pamphlets, Nineteenth-Century American Drama, Early American Newspapers, and American Broadsides and Ephemera. Although badly written, the play exploded American theatergoers’ expectations and contributed to the evolving art of stagecraft. No doubt the costumes of the ladies of the ballet also broke old barriers.

For more information about access to Readex products at your institution, please contact Readex Marketing.