“An equality of wages”: The Evolution of Working Women’s Rights, as Captured by Early American Publications

Among the United States’ earliest and most fervent supporters of working women’s rights was an Irish immigrant named Mathew Carey, who arrived in Philadelphia in 1784. In that city he established a publishing business and a book store, and used his expertise to print broadsides and pamphlets that advocated for progressive causes.

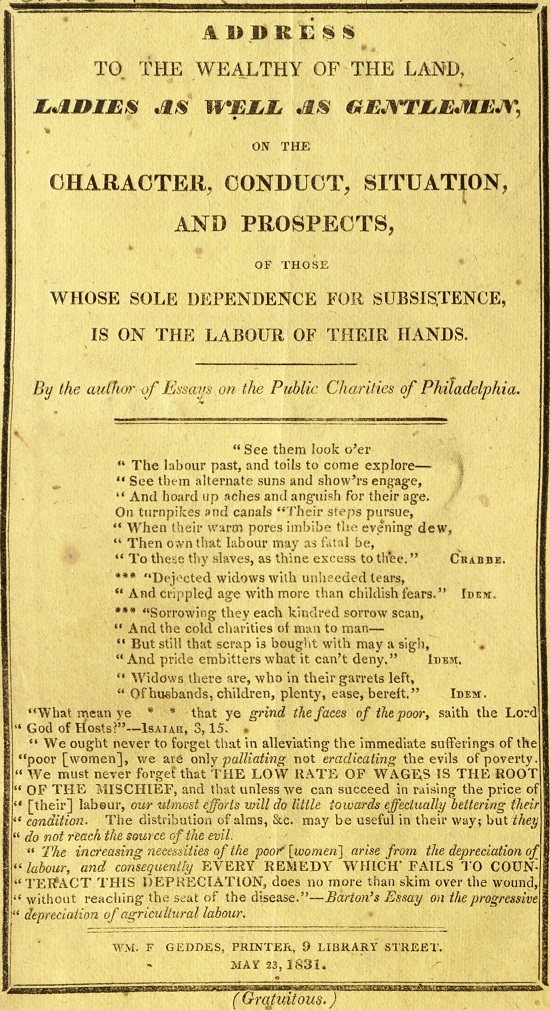

Toward the end of his life, Carey became a champion of poor seamstresses and spoolers, the women who wound cotton or yarn onto spools. In 1831 he wrote a pamphlet titled “Address to the Wealthy of the Land, Ladies as Well as Gentlemen, on the Character, Conduct, Situation, and Prospects, of those Whose Sole Dependence for Subsistence, is on the Labour of their Hands.” The title page includes a quote from “Barton’s Essay on the Progressive Depreciation of Agricultural Labour:”

We must never forget that THE LOW RATE OF WAGES IS THE ROOT OF THE MISCHIEF, and that unless we can succeed in raising the price of [their] labour, our utmost efforts will do little towards effectually bettering their condition….The increasing necessities of the poor [women] arise from the depreciation of labour, and consequently EVERY REMEDY WHICH FAILS TO COUNTERACT THIS DEPRECIATION, does no more than skim over the wound, without reaching the seat of the disease.

This may be one of the earlier instances of an argument supporting working women published in the United States, but it was hardly the last. The work relegated to women was often episodic, subject to changing fancies, and poorly remunerated. Seamstresses may have been the most abused of any class of female workers. Their fate was often degrading—as Carey warned in a broadside, wherein he warned that desperate women will turn to prostitution in order to survive. He quotes “a highly respectable physician in New York, whose name I am not at liberty to mention.” The physician said:

My profession affords me many and unpleasant opportunities of knowing the wants of those unfortunate females, who try to earn an honest subsistence by the needle, and to witness the struggles often made by honest pride and destitution. I could cite many instances of young, and even middle-aged women, who have been ‘lost to virtue,’ apparently by no other cause than the lowness of wages, and THE ABSOLUTE IMPOSSIBILITY OF PROCURING THE NECESSARIES OF LIFE BY HONEST INDUSTRY.

Carey issued several more broadsides between 1830 and 1833, which can be found in American Pamphlets, 1820-1922. Taken together, these documents offer insight into the social and economic context of the time, particularly regarding women workers.

Carey and other observers considered poor men less noble than their wives. As a May 6, 1829, article titled “Women’s Wages” from the Hampshire Gazette in Northampton, Massachusetts, put it,

Poor women are always frugal and industrious; I have observed them very narrowly and I can with confidence say, that they are far more industrious and moral than the men of their own class.

Written by “a respectable woman” from New Jersey, the article concludes that since women “labor equally with the men—that their life is of no longer duration—shewing [sic] an equality of suffering…and that they are fifty percent more moral and industrious than the men—they are fully entitled to an equality of wages.”

The Hampshire Gazette’s editors made sure to point out that they were “not convinced” by this argument. Neither were editors of the Boston Times and the Boston Quarterly Review. In 1840, Dr. Elisha Bartlett responded vigorously in these publications to an 1841 pamphlet titled “A vindication of the character and condition of the female employees of the Lowell mills…”, which described an experiment in which females between the ages of fifteen and 35 were recruited throughout northern New England to work for a few years before returning to their rural roots. These “mill girls” were paid in cash, required to live in company-approved housing overseen by matrons who enforced strict moral codes, and to attend church and classes regularly. However, Bartlett wrote that,

The great mass wear out their health, spirits and morals, without becoming one whit better off than when they commenced labor….the average life, working life, we mean, of the girls that come to Lowell, for instance, from Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont, we have been assured, is only about three years. What becomes of them then? Few of them ever marry; fewer still ever return to their native places with reputations unimpaired.

Bartlett argued strongly for bettering the living standards and nutrition of working women as well as for unimpeachable integrity in the women who ran the boarding houses. But he was a man of his times and could not forebear, when itemizing his wishes for improvements, adding that

I wish that every girl would consult her health and comfort in providing herself with an umbrella, india [sic] rubber over shoes, a warm cloak, woollen stockings and flannel for the winter, instead of sacrificing her pride in the form of parasols, kid shoes, lace veils and silk stockings.

His paternalism foreshadows many subsequent attitudes women would encounter as they began to organize for their rights.

Twenty-one years later, on March 4, 1850, the Philadelphia Public Ledger showed that such organization was starting to take off. An opinion published by the Public Ledger argued for an association of female needle workers to protect them from the vicissitudes of rapacious employers and market conditions. A May 25, 1869, article in the Albany Evening Journal meanwhile, reported on the convention of working women in Boston sponsored by Workingpeople’s League:

There was a mournful and most eloquent tone in the plain, unvarnished stories of suffering told by these poor women….Not only are the wages paid ridiculously low, but those compelled to toil for them must submit to the most tyrannical treatment.

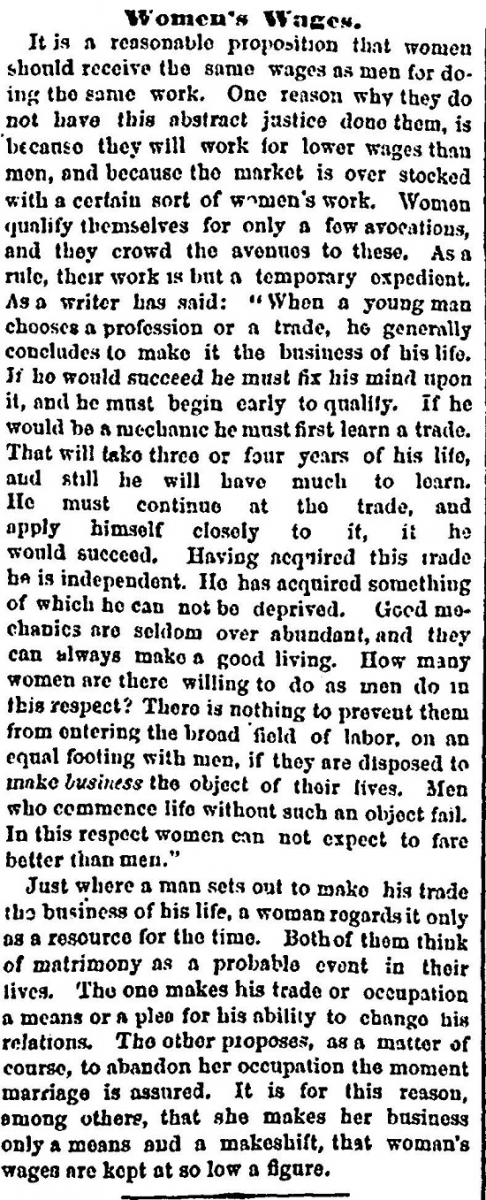

Yet schemes and arguments meant to reduce women’s wages also emerged. The editor of the San Francisco Bulletin in 1857 argued that market forces ought to determine increasing or decreasing wages, and that “a man is, or ought to be, the head of a family, with a wife and children to maintain; while working-girls, as a rule, only have themselves to support.” The Commercial Advertiser, in New York City, published an opinion on March 24, 1869, blaming women for their situation because they “they qualify themselves for only a few avocations, and they crowd the avenues to these. As a rule, their work is but a temporary expedient.” Further, the author posits disingenuously that “there is nothing to prevent [women] from entering the broad field of labor, on an equal footing with men, if they are disposed to make business the object of their lives.”

On March 11, 1870, an article in the Springfield Republican, citing the New York Tribune’s “lively writer, ‘Shirley Dare,’” further reflected the condescension with which many regarded poor women who had no choice but to accept hard work and miserable conditions.

It is very difficult to meet and satisfy the “Bohemian temper” in this class of women, and all the more so, because it leads to and is complicated with the great social evil of illicit love.

While Dare didn't propose any immediately practical solutions to these women’s plight, she made broad suggestions, including somehow reducing the cost of their lodgings and food, bringing them “in contact with private employers” thereby somehow allowing for “the profits of their work [to be] diverted into the proper hands,” and providing “cheap amusements” which will “go farther toward neutralizing morbid discontent than any probable rise of wages can do.”

The Cincinnati Gazette’s Gail Hamilton expressed similar classism and discontent with the movement toward improving women’s wages on December 19, 1870:

When women have once become thoroughly possessed with the importance of keeping their word, the next step toward improving their condition is to improve the quality of their work. Of all the evils which womankind endure, the part which law can cause or cure is infinitesimal compared with that which is caused by their own inefficiency. I think it is not too much to say that good work always brings good price….I am, at the moment, so far from joining in the general outcry concerning the low wages of women, that it seems to me in a large majority of cases women are overpaid.

She went on to compare a “raw, rough, unskilled, untidy Irish servant in a New England kitchen [who] is paid three dollars a week for diffusing discomfort through the house” with a boy leaving high school who is “well educated, well mannered, eager to learn to become useful, to please his employers” and who accepts low wages and fends for himself in finding food and shelter “but is too thankful to be admitted to the house and give his services for the sake of learning the art or trade.”

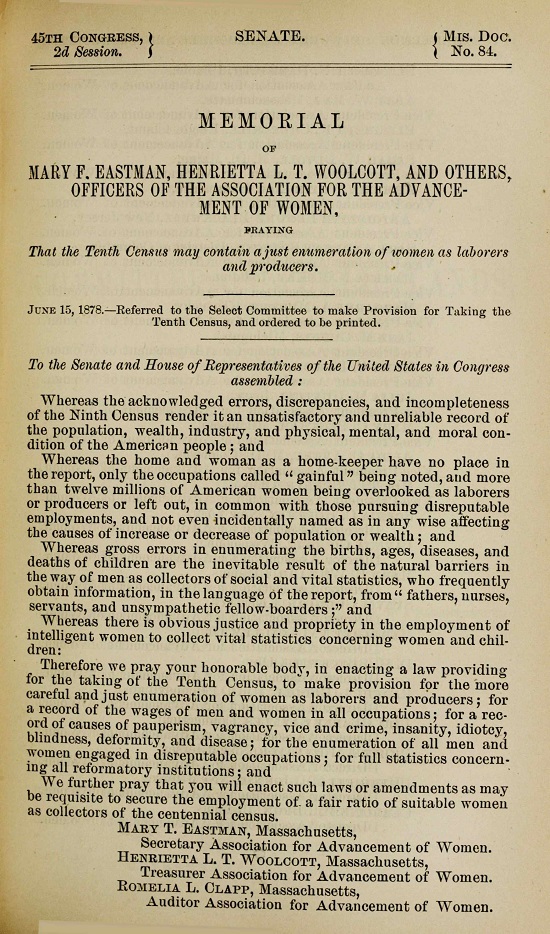

While such newspaper opinion pieces were largely anecdotal, more objective information can be found in the U.S Congressional Serial Set. One document, dated June 15, 1878, was a request to the Senate from officials of the Association for the Advancement of Women “praying that the Tenth Census may contain a just enumeration of women as labors and producers.” Their memorial asked that the Tenth Census include

a record of the wages of men and women in all occupations; for a record of causes of pauperism, vagrancy, vice and crime, insanity, idiotcy [sic], blindness, deformity, and disease; for the enumeration of all men and women engaged in disreputable occupations; for full statistics concerning all reformatory institutions; and We further pray that you will enact such laws or amendments as may be requisite to secure the employment of a fair ratio of suitable women as collectors of the centennial census.

Although in 1870 the Cincinnati Gazette asserted that there was little the law could do to assist poor women laborers, it was indeed the law that finally began to address some of the conditions of their employment. The third annual report of the U.S. Civil Service Commission issued on March 26, 1886, included a section on “Women in the Service,” which asserted that

The Civil Service Law makes no distinction on account of sex. The examinations under it are open alike to men and women. Whatever inequality between the sexes may be found in the numbers appointed arises from the needs and conditions of the service itself, and not from any provisions of the Civil Service rules or any restrictive action of the Commission....women can successfully perform the duties of many of the subordinate places under the Government. In many cases they have shown eminent fitness for the places they have held. There is simple justice in allowing them to compete for the public service, and to receive appointments to places suitable for them, when, in fair competition, they have shown superior merit.

There are caveats in the commissioner’s message; “subordinate positions” and “places suitable for them” are fraught with unarticulated conditions. Still, the most significant condition is that “the determination of the question whether a woman or a man shall be selected to fill any given vacancy must be left, under the law…to the appointing officer, who alone knows the situation and who is responsible for the successful operation of his office.”

This progress in using the law to ameliorate working conditions for women, however glacial, was nonetheless increasingly evident in newspapers and government documents. In 1892, after an advertisement in the Washington Daily Star noted that “The Civil Service Commission is in urgent need of men stenographers and typewriters,” Congress intervened to inquire why qualified women weren’t welcome. The answer was again that the department heads are free to make any decision as to whether or not to hire women.

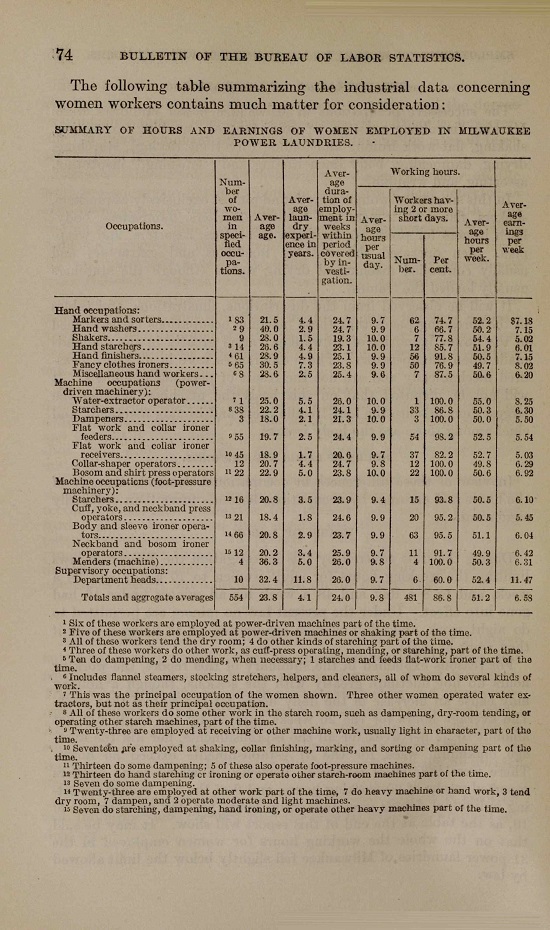

A U.S. Department of Labor bulletin for April 10, 1913, was titled “Ten-hour maximum working-day for women and young persons.” A month later the Bureau of Labor Bulletin published the third issue of its Women in Industry Series, which included an examination of the employment of women in power laundries in Milwaukee and a summary of their wages and hours. The highest weekly wage, other than that of supervisors, was $8.25 paid to the water-extractor operator, but the average rate for all women (including 10 department heads) was $6.58 a week, with an average workweek of 51.2 hours. In 2019 dollars, this is equivalent to approximately $25.87—a weekly wage for more than 50 hours of labor.

In the years to come, the U.S. Bureau of Labor continued to release its statistics bulletin, often focusing on the District of Columbia. In 1914, however, the bulletin reported on “Wages and regularity of employment and standardization of piece rates in the dress and waist industries: New York City,” and soon the publications expanded to assess Indiana, Oregon, Massachusetts and Michigan, among other states. As the number of locations grew, so did the types of labor covered, from seamstress to retail workers to civil service. The U.S. Congressional Serial Set provides these and numerous other primary sources that document the evolution of the rights of America’s working women and the occupations and conditions to which they were restricted or dismissed.

For more information about Readex products for teaching and research in Women's Studies and related fields, please contact Readex Marketing.