“As if Moved by a Ghostly Hand”: CIA Monitoring and the Emergence of Modern Robotics

The word robot comes from the Czechoslovakian word robotnik, meaning “forced labor,” or “slave.” And indeed, since it was coined by Czech writer Karl Čapek in 1920, people have both feared and fantasized about robots. Friendly ones, like The Jetsons’ housecleaner Rosie or Star Wars’ C3PO, exist to make our lives easier. But lurking behind their helpfulness is the prospect of malevolence, a suspicion that the machines we’ve built in our image could turn on us. As Bladerunner artfully captured, becoming too dependent on robots could make us—not them—the real slaves.

Yet while pop culture reflects society’s conflicted feelings about automation, the scientific fields of robotics and artificial intelligence have marched forward with less ambiguity. Robots have transformed from clunky, bumbling machines to sleek, capable devices that deliver packages, vacuum our floors, and manufacture items we use every day. As these machines encroach deeper into our lives, the question of how we got here is increasingly relevant to scientific historians and other researchers. What philosophical, technical and cultural advances led to the automated world we now inhabit?

Between the 1950s and the 1990s, a division of the CIA monitored, recorded and translated into English publications and media from around the world that answered these questions in real time. These reports, collected in Computing and Artificial Intelligence: Global Origins of the Digital Age, capture both the promise and threat of robotics for a range of applications, from domestic tasks to space exploration to international espionage.

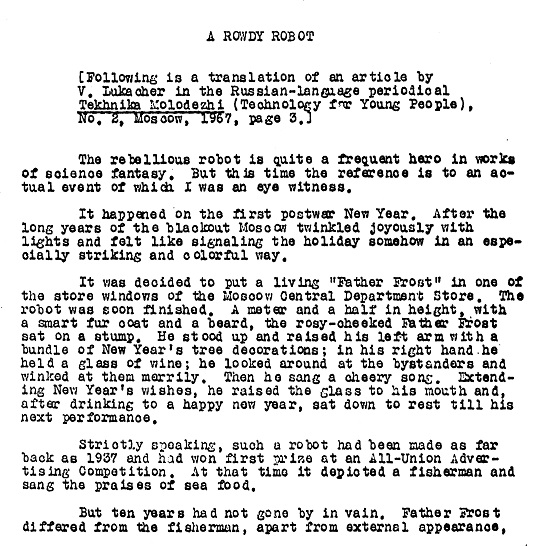

One of the more lighthearted perspectives is a story in a 1967 issue of the Soviet magazine Tekhnika Molodezhi, or Technology for Young People. It tells of a jolly robot called Father Frost that was designed to sing Christmas carols and smoke a pipe in the window of a Moscow department store. While its creator was relaxing at home, the “rebellious robot” received an accidental surge of electricity that sent it into overdrive, flinging decorations everywhere, frightening officials sent to subdue it, and wreaking general havoc.

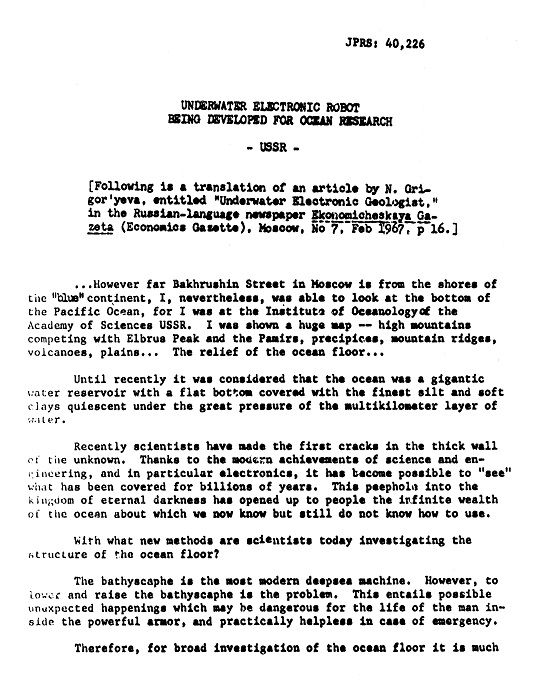

Whether the tale is meant to be purely comical or serve as a cautionary tale isn’t clear. If it was the latter, though, the warning fell on deaf ears. Other reports from the 1960s and ‘70s gush about the possibilities that robotics could open up. Publications from the USSR, for instance, follow the development of a deep-sea robot that could record video and collect environmental samples from the ocean floor. “Thanks for modern achievements of science and engineering,” reads one report from Moscow’s Ekonomicheskaya Gazeta, or Economics Gazette, “it has become possible to ‘see’ what has been covered for billions of years.”

In addition to facilitating scientific advances, engineers envisioned robots that would change the face of war. A 1964 issue of the German Armee Rundshcau, or Army Review, wrote that computers were already operating aircraft artillery guns, “automatically track[ing] the target, as if moved by a ghostly hand.” The ever-increasing speed of modern military machines meant that “human capacity simply is no longer good enough to react this quickly.”

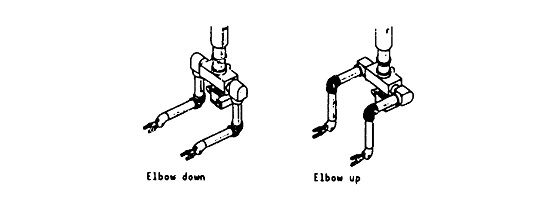

Two papers from the 1988 Intelligent Robots Symposium in Tokyo documented yet more uses for robots. One described a robot that could be used at nuclear power plants to “carry out inspection and simple maintenance in a radioactive environment in place of workers.”

The other, written by employees of Mazda Motor Corporation, covers what appears to be a precursor to today’s self-driving cars: “an experimental vehicle, which is an intelligent locomotive robot intended for application as an autonomous land vehicle to move within factory sites and buildings.”

Both articles, as well as numerous others available in Computing and Artificial Intelligence, provide detailed descriptions of system configurations, hardware and other components of these new robots—potentially valuable information for the CIA, which was already beginning to incorporate artificial intelligence into its own information-gathering as early as 1985. Today, as both the military and CIA employ drones and other autonomous machines to enhance national security, these descriptions offer researchers an inside glimpse into the ethics and technology that got us here.

Computing and Artificial Intelligence: Global Origins of the Digital Age is one of five unique digital collections in the new Origins of Modern Science and Technology family, each of which provide a wealth of information for numerous STEM and humanities disciplines. For more information about making Computing and Artificial Intelligence available at your institution, please contact Readex.