“A Population Excitable As Ours”: Highlights from American Pamphlets, 1820-1922: From the New-York Historical Society

Posted on 03/03/2015

by

Many of the works in the February 2015 release of American Pamphlets concern slavery and the American Civil War. Included are narratives about former slaves, arguments that slavery is ordained by God, arguments against slavery and for abolition, an essay on how to manage one’s slaves, and a detailed accounting of the cost of the Civil War to each town in one New England state. Among the authors of these pamphlets are two great writers, Victor Hugo and John Greenleaf Whittier.

Victor Hugo’s Letter on John Brown, with Ann S. Stephens’ Reply (1860)

In 1860, the great French writer Victor Hugo sent a letter to a London newspaper in defense of John Brown and his raid on Harper’s Ferry. Hugo’s letter was reprinted in many American newspapers, which was worrisome to Ann Stephens, an author and magazine editor. In reply to Hugo’s letter, Stephens wrote, “The literary reputation of Victor Hugo is calculated to give a force to the wild eloquence of his letter, which should not be allowed to make its way, unanswered, into a population excitable as ours.”

She asserts it is this passionate style that led to the events at Harper’s Ferry and “is fast destroying the holy brotherhood of which our Constitution was the bond and seal.”

Hugo’s letter, written after the Harpers Ferry trial but before the executions, is reproduced within this pamphlet. Hugo is astonished that these events, including the trial which he describes in withering prose, are taking place “not in Turkey, but in America.” He asserts that should Brown be executed his executioner “would be – though we can scarce think or speak of it without a shudder – the whole American Republic.”

In her letter to Hugo, Stephens asserts that if ardent enthusiasm could carry the day he might have saved Brown, “but all the eloquence of genius cannot take the blackness from treason, or the crimson stain from murder. It requires something more than an out-burst of fine poetry to turn crime into patriotism…”

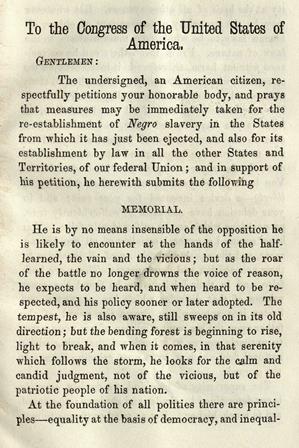

Memorial of David Quinn Advising the Re-establishment of Negro Slavery (1866)

Mr. Quinn addressed this memorial to the United States Congress with the purpose of reestablishing slavery in the South as well as in all of the territories and in “all other States.” He allows that his proposal is likely to be opposed by “the half-learned, the vain and the vicious” but is confident that he will be heard “and his policy sooner or later adopted.”

He argues that just as with breeds of dogs “so do the various species of men require different rules and forms, privileges and restrictions, for the regulation of their aggregation in associated life.” Quinn also confidently describes the “Eternal Negro” as having a brain that “is from ten to fifteen percent smaller than Caucasian’s, and at the same time, darker colored and differently disposed.”

Apparently, at least according to Quinn, the Negro has a larger nervous system than the white man and this allows the slave to endure the tribulations of his service as he is somewhat immune to humiliation. There are many other pseudo-scientific arguments put forth, all of them in support of the thesis that the African was more or less divinely intended and fitted for being a slave.

Although many of Quinn’s arguments are economic, and he lays them out accordingly, he also offers an additional reason based on immigration. Suggesting that the government is allowing the country to be overrun by low-value immigrants taking jobs away from citizens, Quinn points out that by reinstituting universal slavery for all Africans in every state and territory, and by bringing back the slave trade, America will have its own means of obtaining and breeding a malleable labor force that will obviate the need to allow entry to any more unsavory immigrants.

Report of the Commissioners upon the War Expenditures of the Towns and Cities in the State of New Hampshire (1866)

The cost of the Civil War was enormous, especially the cost of life and limb. But this accounting for its financial and material expenses provides a different insight into the nature of the war and quotidian process of paying for it.

This is a report from the New Hampshire commissioners charged with the accounting of the bounties paid, and the recruiting expenses incurred, for the duration of the war by each municipality in the state. The expenses are broken out by county and town or city.

The commissioners are attempting to reconcile discrepancies in costs and bounties in order to find a fair way for the state to compensate the municipalities. This is also necessary in order for the state to seek compensation from the federal government. Documents like this may seem dry, but it is often fascinating to examine and consider them within the context of the larger events of the time.

Victor Hugo’s Letter on John Brown, with Ann S. Stephens’ Reply (1860)

In 1860, the great French writer Victor Hugo sent a letter to a London newspaper in defense of John Brown and his raid on Harper’s Ferry. Hugo’s letter was reprinted in many American newspapers, which was worrisome to Ann Stephens, an author and magazine editor. In reply to Hugo’s letter, Stephens wrote, “The literary reputation of Victor Hugo is calculated to give a force to the wild eloquence of his letter, which should not be allowed to make its way, unanswered, into a population excitable as ours.”

She asserts it is this passionate style that led to the events at Harper’s Ferry and “is fast destroying the holy brotherhood of which our Constitution was the bond and seal.”

Hugo’s letter, written after the Harpers Ferry trial but before the executions, is reproduced within this pamphlet. Hugo is astonished that these events, including the trial which he describes in withering prose, are taking place “not in Turkey, but in America.” He asserts that should Brown be executed his executioner “would be – though we can scarce think or speak of it without a shudder – the whole American Republic.”

In her letter to Hugo, Stephens asserts that if ardent enthusiasm could carry the day he might have saved Brown, “but all the eloquence of genius cannot take the blackness from treason, or the crimson stain from murder. It requires something more than an out-burst of fine poetry to turn crime into patriotism…”

Memorial of David Quinn Advising the Re-establishment of Negro Slavery (1866)

Mr. Quinn addressed this memorial to the United States Congress with the purpose of reestablishing slavery in the South as well as in all of the territories and in “all other States.” He allows that his proposal is likely to be opposed by “the half-learned, the vain and the vicious” but is confident that he will be heard “and his policy sooner or later adopted.”

He argues that just as with breeds of dogs “so do the various species of men require different rules and forms, privileges and restrictions, for the regulation of their aggregation in associated life.” Quinn also confidently describes the “Eternal Negro” as having a brain that “is from ten to fifteen percent smaller than Caucasian’s, and at the same time, darker colored and differently disposed.”

Apparently, at least according to Quinn, the Negro has a larger nervous system than the white man and this allows the slave to endure the tribulations of his service as he is somewhat immune to humiliation. There are many other pseudo-scientific arguments put forth, all of them in support of the thesis that the African was more or less divinely intended and fitted for being a slave.

Although many of Quinn’s arguments are economic, and he lays them out accordingly, he also offers an additional reason based on immigration. Suggesting that the government is allowing the country to be overrun by low-value immigrants taking jobs away from citizens, Quinn points out that by reinstituting universal slavery for all Africans in every state and territory, and by bringing back the slave trade, America will have its own means of obtaining and breeding a malleable labor force that will obviate the need to allow entry to any more unsavory immigrants.

Report of the Commissioners upon the War Expenditures of the Towns and Cities in the State of New Hampshire (1866)

The cost of the Civil War was enormous, especially the cost of life and limb. But this accounting for its financial and material expenses provides a different insight into the nature of the war and quotidian process of paying for it.

This is a report from the New Hampshire commissioners charged with the accounting of the bounties paid, and the recruiting expenses incurred, for the duration of the war by each municipality in the state. The expenses are broken out by county and town or city.

The commissioners are attempting to reconcile discrepancies in costs and bounties in order to find a fair way for the state to compensate the municipalities. This is also necessary in order for the state to seek compensation from the federal government. Documents like this may seem dry, but it is often fascinating to examine and consider them within the context of the larger events of the time.

For more information about American Pamphlets, 1820-1922, or to request a trial for your institution, please contact readexmarketing@readex.com.