“Dip not thy meat in the sauce”: Highlights from the American Antiquarian Society’s Supplement to Early American Imprints, Series II

February’s release of Early American Imprints, Series II: Supplement 3 from the American Antiquarian Society includes rare books for children which are intended to inform and instruct them. They include behavioral and etiquette instruction and, in one case, graphic as well as moral illustrations.

Jacky Dandy’s Delight: Or, The History of Birds and Beasts; in Verse and Prose. Adorned with Cuts (1805)

No author of this imprint is identified, but the publisher, Ashbel Stoddard, proves to be an interesting person. The citation provides this “Publication Information: Hudson (N.Y.): Printed by Ashbel Stoddard at the White House, corner of Warren and Third Streets, 1805.” Stoddard was one of the first printers in the early days of white settlements in the Hudson Valley. He owned a bookstore and published a newspaper. The relief prints are charmingly primitive and the book is intended to instruct children about natural history and good behavior.

Jack Dandy was an active fellow,

Merry as any Punchinello,

And did the Part of Harlequin;

Here do but look, he’s just come in.

Good Mr. Har. Instruct me pray,

How I may be a pretty boy.

Says Harlequin, I’ll grant your suit,

Learn to be good, and that will do’t.

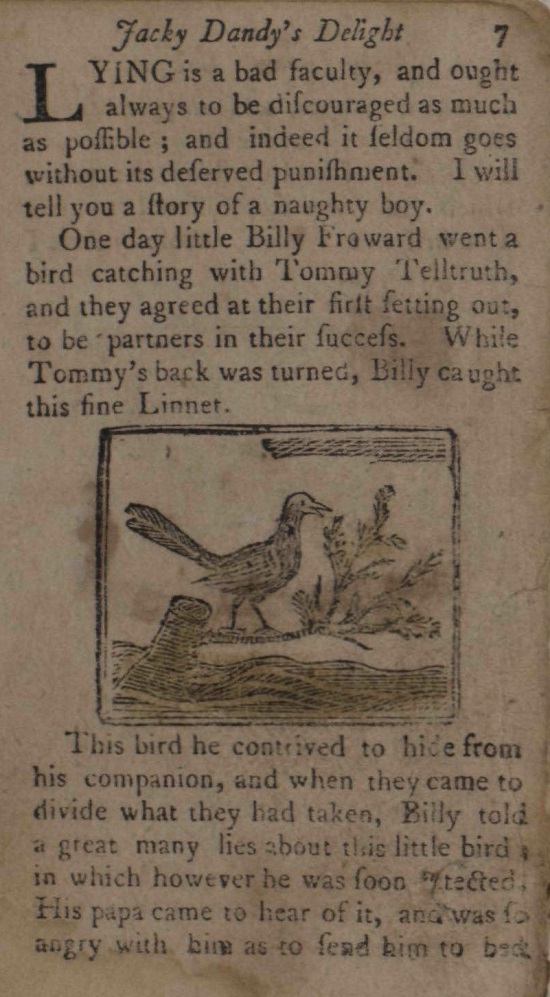

The author weaves moral lessons with illustrations and descriptions of the birds and beasts. As an instance, we meet Billy Froward who “went a bird catching with Tommy Telltruth, and they agreed at their first setting out, to be partners in their success.” But Billy is a treacherous lad who attempts to hide the linnet he has bagged from Tommy.

Billy told a great many lies about this little bird in which however he was soon detected. His papa came to hear of it, and was so angry with him as to send him to bed without supper, and whipped him into the bargain; besides this, there was a collection of wild beasts in the town, which Billy was not suffered to see. The first of which was a Lion, whose picture I here give you.

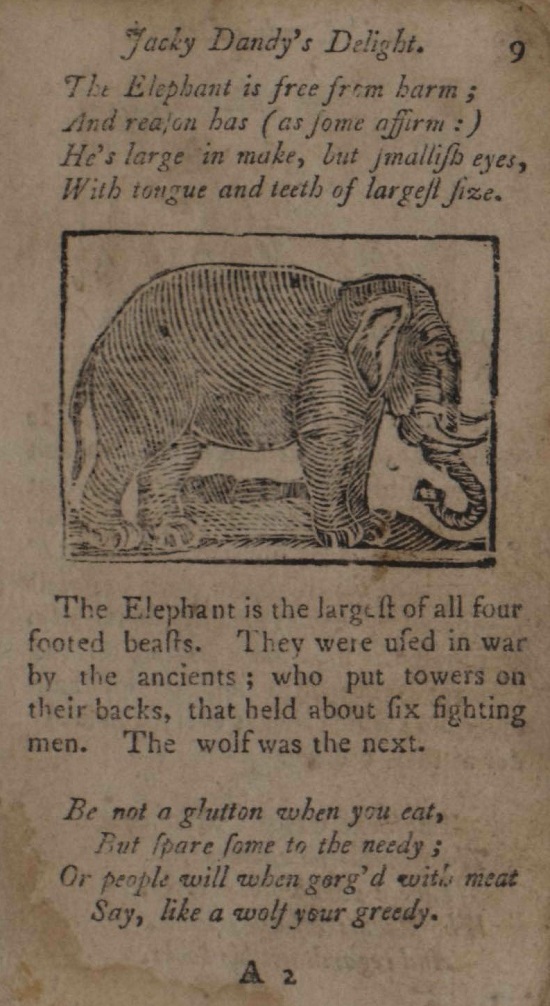

Some of the animals, such as the elephant, are favorably described in behavior and temper while others, such as the wolf, come in for severe criticism.

Be not a glutton when you eat,

But spare some to the needy;

Or people when gorg’d with meat

Say, like a wolf your [sic] greedy.

The wolf is a savage beast. He comes down from the mountains and forests, and devours every thing that comes in his way; and with a full belly, kills the poor innocent lamb, tho’ he cannot eat it. He may be well compared to those naughty boys, who wantonly kill flies and caterpillars, and torment other little animals for their diversion; which makes every one shudder at their cruelty.

The monkey is reputed by some to be able to speak but chooses not to “lest he should be set to work. Herein he resembles naughty little boys who will not learn A, lest they be obliged to learn B too.”

Subsequently, the author turns from beasts to birds.

It is a saying among children, that The Robin and the Jenny Wren, Are Jacky Dandy’s Cock and Hen.

For this reason all good girls and boys are particularly careful not to hurt either of these pretty birds; for none will dare to molest those whom Heaven has thought proper to take under its protection.

The goose also serves an instructive purpose for civilizing children.

I fancy it is on account of her continual prating that this bird came to be so generally reproached with folly. We say, As silly as a Goose. And to be sure it is very foolish, like this silly bird, to be always gabbing. You must learn, my dear, to improve from the conversation of others; which you can never do if you are always talking yourself.

Finally, the author concludes:

Thus I have endeavored to shew the difference of disposition even in Birds and Beasts; and hope you will make proper use of the observations I have made on them. As for Billy Froward, he was so mortified at not seeing the wild Beasts, that he promised never to tell fibs any more.

The School of Good Manners: Composed for the Help of Parents in Teaching Their Children How to Behave during Their Minority (1804)

The citation for this imprint states in the Notes section that this is “Compiled by Eleazer Moody. Substantially derived from an English work of the same title written by John Garretson.” Researchers who have drawn on similar early 19th-century children’s literature will likely recognize passages of the text. The Preface makes clear the intent of the author.

It is acknowledged by almost every one, that a good carriage in Children is an ornament not only to themselves, but also to those from whom they descend….Whereas Children of but a mean, careless, or ill breeding bring disgrace on their Parents, as well as contempt on themselves. This little Book is composed for the help of parents, in teaching their Children how to conduct themselves during their minority. And it is humbly recommended to Instructors to introduce it into their Schools, as it is proper to be taught to Children. For we read, Prov. Xxii. 6. Train up a child in the way he should go; and when he is old he will not depart from it.

The second chapter lays out 143 “rules for Children’s Behavior”… at church, at home, at meals, at school and in other instances. Some of the rules seem reasonable, but others will appear oppressive in this century. In church:

Decently walk to thy seat or pew; run not nor go wantonly.

Sit where thou art ordered by thy superiors, parents or masters….

Be not hasty to run out of the meetinghouse when worship is ended, as if thou wert weary of being there.

Walk decently and soberly home, without haste or wantonness, thinking upon what you have been hearing.

A child’s behavior at home was similarly restrictive.

If thou passest by thy parents at any place where thou seest them, bow toward them. Never speak to thy parents without some title of respect, as sir, madam, &c. Bear with meekness and patience, and without murmuring or sullenness, thy parents’ reproofs or corrections; nay, though it should happen that they be causeless, or undeserved.

Rules for behavior at the table are akin to those for church or other home occasions.

Ask not for any thing, but tarry till it be offered thee….

Speak not at the table; if thy superiors be discoursing, meddle not with the matter; but be silent, except thou art spoken unto….

Stare not in the face of any one (especially thy superiors) at the table….

Dip not thy meat in the sauce….

Smell not of thy meat, nor put it to thy nose; turn it not the other side upward to view it upon thy plate.

Throw not anything under the table….

Frown not nor murmur if there be any thing at the table which thy parents or strangers with them eat of, while thou thyself hast none given thee.

In company the child was scarcely less inhibited.

Enter not into the company of superiors without command or calling, nor without a bow.

Put not thy hand in the presence of others to any part of thy body not ordinarily discovered….

Stand not wrigling [sic] with thy body hither and thither but steady and upright….

Spit not in the room, but in the fireplace, or rather go out and do it abroad….

Spit not upon the fire, nor sit too wide with thy knees at it.

Not surprisingly, the rules for school deportment are rigorous.

At no time quarrel or talk in the school, but be quiet, peaceable and silent. Much less mayest thou deceive thyself, in trifling away thy precious time in play.

If thy master speak to thee, rise up and bow; making thy answer standing….

Make not haste out of school, but soberly go when thy turn comes, without noise or hurry.

Go not rudely home through the streets, stand not talking with the boys to delay thee, but go quietly home, and with all convenient haste….

Divulge not at any person whatever, elsewhere, any thing that hath passed in the school, either spoken or done.

The remaining text leans heavily on Protestant teachings and Biblical references which includes an expiation on the ten commandments as applied to children and a standard catechism.

The Godmother’s Tales. By the Author of Short Stories, Summer Rambles, Cup of Sweets, &c. &c. (1818)

Many books for children in the early 19th century entail dreadful consequences for naughty boys and girls. These stories are more gentle and of a sweeter nature although not without peril and challenges. Possibly godmothers were regarded as kind and loving rather than upbraiding and punitive. Whatever the case, these stories are, like so many books for children, meant to instruct and guide the young mind.

The author is Elizabeth Sandham whose other works suggest a strongly Christian intent, perhaps most particularly in her “The History and Conversion of the Jewish Boy” which is credited as one of the first conversion novels intended for children. In this collection of tales Sandham seeks to provide uplifting morals for children to consider. The first story, The Stolen Jack-ass, is largely the account of a good boy making well. He encounters some difficulties, but they are hardly insurmountable. Suffice it to say that an industrious young lad creates a remunerative service, cleverly expands it and provides comfort and ease to his impoverished family, is thwarted and faces catastrophe but is swiftly rescued and all ends well. The God-mother narrator concludes by saying that the tale “struck me so much, that I made a memorandum of the heads of it before I went to bed, concluding that the perusal of it would give pleasure to my dear God-daughter.”

By the standards of contemporary instructive stories for children the protagonist of “The Naughty Boy Punished” gets off relatively lightly—he survives his comeuppance. The God-mother recounts a litany of bad-tempered jokes young George has played, usually to the harm of others, culminating in a particular cruelty which ends badly for him.

The poor girl burst into tears, and George laughing, asked her why she did not take hold of the handle; but his laughing was, in an instance turned to screams, and bitter lamentations, for turning to run away, the milk had made the ground so soft, that his foot slipped, and he fell with his leg under him, and broke it just above the ancle [sic].

Nobody was sorry for the accident, and when it was told that he would be confined three months or more, the people in the village said: “So much the better, he will be out of the way of doing mischief.”

As naughty as George was, Charles was good. Having a wealthy father and a comfortable life, this boy was also liberally educated. When he encounters a fisherman who is poor, but good, whose wife is illiterate, but good, who fear their only child will never learn to read or write. Charles undertakes to tutor the boy during his break from his own lessons. His father begins to wonder at his absences and suspects the worst. Upon investigation he discovers the happy truth and rewarded his exemplary child.

…he was very much applauded, and was the very next morning taken into the town, where he was presented with a great number of very pretty books, both for himself and Joe, with an ink-stand for him, and a good quantity of writing paper and pens and ink. Charles was the happiest of all creatures, when he scampered away to the fisherman’s hut, his little hands filled with the parcels, and his heart beating with joy; and his pleasure was increased when he spread out his presents on the kitchen table, to the wondering eyes of Joe and his mother.

Possibly, there is a cloying quality to these tales, but the author embodies the important viewpoint of her era and place that Christianity must be paramount in the instruction of children.

For more information about Early American Imprints, Series II: Supplement 3 from the American Antiquarian Society, 1801-1819, please contact Readex Marketing.