“He saw the folly of it, and died”: Highlights from Nineteenth-Century American Drama

There are over 200 scripts whose authorship is credited to Anonymous in Nineteenth-Century American Drama: Popular Culture and Entertainment, 1820-1900. An examination of these titles suggests several categories into which many of these can be sorted. Thirty of these are “Ethiopian” or other less cautious euphemisms. Others are meant for school exercises or home entertainment, while still others are the scripts of unique college or club, church, and charity productions. Some of the dramas seem to have been commissioned for specific celebrations, usually political or historical. There are also scripts that deal with sensitive or social issues that were controversial in their time. These are among the most interesting plays attributed to Anonymous.

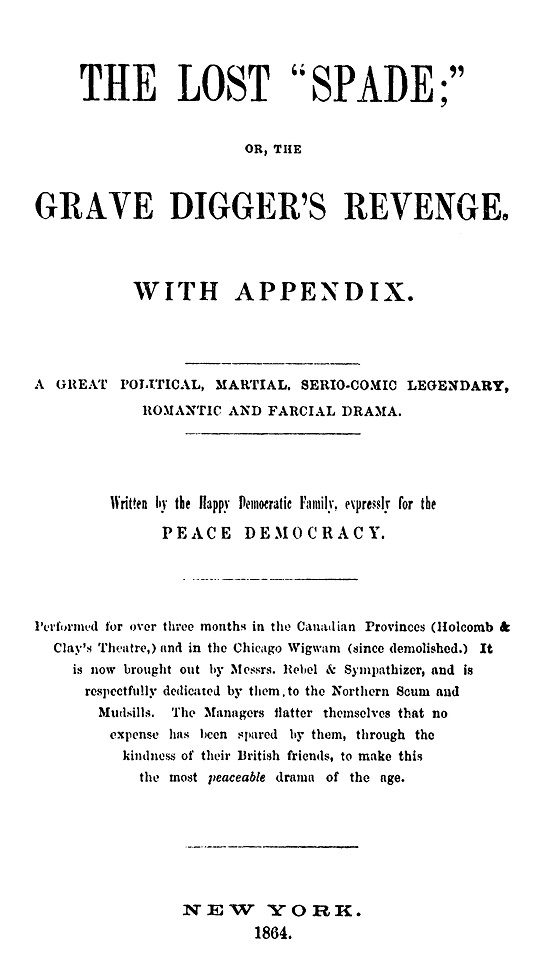

The Lost Spade; or, The Grave Digger’s Revenge (1864)

This political drama was published when the American Civil War still raged. The title page offers a further subtitle: “A great political, martial, serio-comic legendary, romantic and farcial [sic] drama.” It also notes that it was “Written by the Happy Democratic Family, expressly for the Peace Democracy.” The Peace Democracy refers to the Copperheads who were also called Peace Democrats. These Democrats were opposed to the war and favored appeasing the Confederacy. In 1864 prominent Copperheads were put on trial for treason.

Because this script focuses on this dissident bloc of northern Democrats, some of whom were prone to violence, the author may well have had sufficient reason to write anonymously. He provides staging directions and a cast list.

Costume.—Olive Leaves and Branches.

Music. —Drums and Fifes ignored.

Scenery.—Peaceful Abodes, Doves in the Background.

Appointments.—Harmony—all in Harmony.

LOOK AT THE FOLLOWING CAST:

Aristocrat, Mr. Bell Monte.

Grumbler, Mr. Saymore.

Sniveller, Mr. Wud.

Hypocrite and Martyr, Mr. Val-an-gh-m.

“Bully” Boy, Little Georgie.

Naughty Boy, Big Georgie.

Servant, Mr. Marbull.

The play is written in free verse. There are references to “Lincoln’s myrmidons” and worse: Lincoln the Traitor. Treason is afoot:

Grumbler. What ho! my friend, this darkness best be fits ye.

Hypocrite. If here we plotted treason, then thy words are true.

Aristocrat. Treason! ‘tis a word of light import,

And so ill defined that we, good friends, know not its meaning.

The Aristocrat worries that Lincoln will “make me the victim of a fearful goak [joke]. Subsequently, he pumps for an armistice.

Aristocrat. Aye! an armistice. Our friends are wounded bad.

Ulysses now with fearful grip has seized good Lee,

And Richmond feels the want of bread and bacon.

While in Atlanta, Sherman plants his flag,

And Hood before him flees, a vanquished man.

Now, if with armistice we stem the tide

And give our friends the breathing time they need,

We shall, most noble friends, best help the cause of treason.

The plotters talk of gaining power by lying to the electorate and dismissing them. They plan to resort to violence including inducing the New York City draft riots of 1864. When Sniveller mildly objects to unleashing the violent Bully Boy, Hypocrite responds:

Hypocrite. Why mind the means?—‘tis power we want.

Once in the capital, the country we can sell,

And, laughing at the people we have duped,

Welcome our warrior, Jeff., with cordial greeting.

The sentiments of the author begin to emerge in the stage directions that end the Third Act: “Upon the map dances the skeletons of eighty thousand soldiers who lost their lives on the Peninsula…” There follows an announcement:

Grand Interlude

[A considerable time elapsing between the third and fourth acts, it is necessary that something shall be done to make this grand peace drama perfect in unity of time, place and action. Therefore, the management have the pleasure of stating that they will now introduce to the audience the great peace-shrieker of New York City, Samuel Barlo, Esq., who will sing the following poetic effusion. N.B. – During this song no crumbling of peanuts allowed.]

In his song, Barlo refers to “the great Vallandighamer” whom he claims is “under our banner;” Clement Vallandigham was U.S. Congressman from Ohio in 1846 and ’47. He was a leader of the Copperheads, and was arrested and tried by a military commission in Ohio. Lincoln deported him to the Confederacy. Vallandigham then moved to Canada and from there ran for Governor of Ohio. He lost. In the postwar years he ran and lost several times for various positions. He died in 1871, having accidently shot himself with a pistol in his abdomen.

At the conclusion of the play, Lincoln has been reelected.

Servant. All is lost! Old Lincoln carried every State but Jersey.

Hypocrite. Ohio gone for Lincoln? Then let me die; I cannot thus survive this grievous blow.

[Takes poison by eating a copy of the “World.” Dies.]

The play’s final instructions, alluding to the draft riots, read:

[All the actors having left the stage, and as a Lincoln torchlight procession is passing, the curtain falls in honor of the unexpected though welcome death of so many rascals at the same time. The American Eagle now appears with a greenback in each claw, and a copy of the Constitution unabridged in his beak. The Star-Spangled Banner envelopes the sacred bird, and from the distance comes a solemn voice uttering those memorable words: Bully for Old Abe! Echo from Petersburg: Hunky boy is General Grant.]

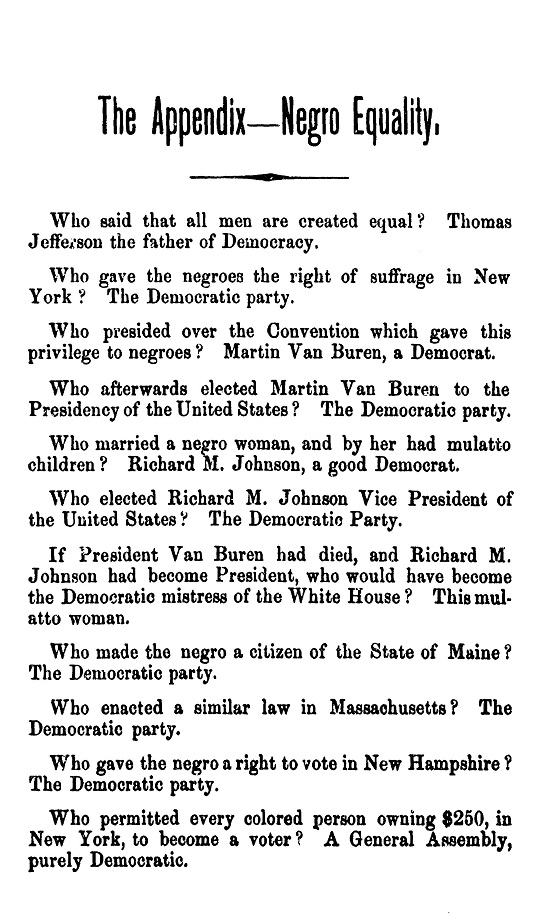

There is an appendix entitled “Negro Equality” which attributes to Democrats all advances for African Americans or “Negroes.” It concludes:

Who, with the above facts and many others staring them in the face, are continually whining about “negro suffrage” and negro equality? The Democratic party.

All these things were done by Democrats, and yet they deny being in favor of negro equality, and charge it upon the Republicans—just like the thief who cries “stop thief” the loudest.

Deseret Deserted; or, The Last Days of Brigham Young. Being a Strictly Business Transaction, in Four Acts and Several Deeds, involving both Prophet and Loss (1858)

The title indicates the irreverent attitude of the author. The play is dated 1858, the second year of the Utah War which was also known by several other names, including the Utah Expedition, the Mormon War, Buchanan’s Blunder, and the Mormon Rebellion. It was in September of the previous year that a wagon train of at least 120 men, women, and children was waylaid and massacred by Mormon militiamen in what became known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

At the outset of the play, Tom Scott and Luny O’Flab are discovered sleeping on a prairie. They are in pursuit of O’Flab’s wife of whom he says “there wasn’t a better little woman in New York a couple of years ago, whin she tuk to reading.” Apparently, Mrs. O’Flab has gone over to the Mormons. The pursuers meet up with a trader named Sparks who signs onto their mission. In Scene II we meet Susan (O’Flab) and Marian in a Salt Lake City garden.

Susan. [To Marian.] Are you quite dressed?

Marian. Not quite yet. This fig-leaf basdue doesn’t set very well. How I hate this horrid ceremony!

Susan. So do I, Marian dear. Oh how I wish we were back at Madame Blancmange’s school together in Union Square.

Marian. So do I, with all my heart. But you see I caught a fit of the revival, and having had a quarrel with Looy Sparks, came of [sic] in a huff to Utah.

Susan. And I emigrated with my father, poor man. He saw the folly of it, and died.

Sparks, O’Flab, and Tom sneak up to the garden wall and peer over. Soon, both Tom and Sparks have recognized their wives, Susan and Marian, and Sairey descried her husband O’Flab. We next meet Young Brigham and Brigham Young discussing the status of “the Gentile troops.” They move onto an alluring topic.

Young Brig [re the troops]. They have given themselves up to junketing and revelry. There came a Gentile merchant among them at Fort Bridger—his name was George Saunders—who brought with him a number of iron houses and a dressing-case full of bottles.

Brig. What had he therein?

Young Brig. A potent and pleasing beverage, as I suppose of French extraction—for they call it “Old Bourbon.”

He hands a bottle to Brigham informing him the remainder awaits his pleasure. Subsequently, Brigham, having dismissed his son, gets very drunk and before passing out goes on a protracted rant. He has a dream of being in one of the gardens of Mahomet’s Paradise. They compare their roles as prophets and compete for having the largest harems.

While Brigham dreams, the women are whipping up a rebellion among the wives. At one point in his repartee with Mahomet, Brigham declares “I am not an American. I am a Mormon.” At another moment the actor playing Brigham steps out of character, addresses the audience directly, and sings a lament.

Back to the play. The women, in rebellion, have moved to a camp. The men stay behind to watch the Mormons and are captured and doomed to be hanged. A pitched battle ensues. Brigham and other church leaders are slain as are O’Flab and Tom. At the curtain, the actor who played Brigham refuses to leave the stage, demanding he be carried as he is, after all, dead. The others finally lure him off with liquor.

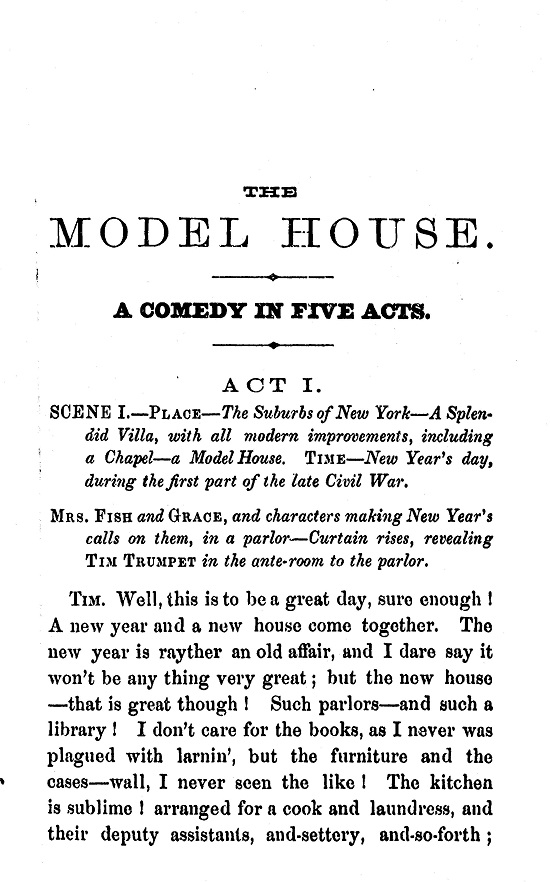

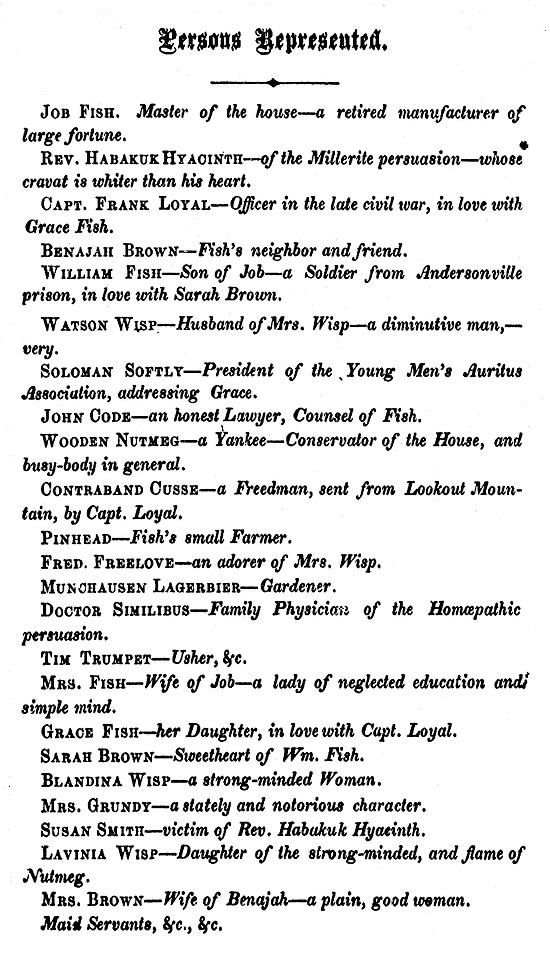

The Model House: A Comedy in Five Acts (1868)

This is a substantial script running to 110 pages. Among the cast are the wealthy Fish family, Rev. Habakuk Hyacinth, Mr. and Mrs. Wisp, Fred. Freelove, and Doctor Similibus.

Many contemporary controversial topics are addressed in this play, including Millerites, the Bloomer costume, women’s rights, homeopathy, seances, and the recently concluded Civil War.

The Reverend is clearly drawn from the Millerites, a doomsday cult that had frequently to revise their date for the rapture. In Vermont, the state from which the sect arose, followers neglected their crops and climbed onto their roofs to await their ascension. Subsequently, they suffered intensely, having no provisions for the winter.

As the play begins, Habakuk has installed himself in the Fish mansion, which includes its own chapel, at the bequest of Mrs. Fish whom the playwright describes as “a lady of neglected education and simple mind.” She is prone to malapropisms declaring, for instance, that “we live in rhubarbs of the city.”

Several of the ladies of the neighborhood are in thrall to the Reverend’s exhortations and doomsday prognostication, and their sewing circle is busy preparing a magnificent Ascension Robe for him.

When the easily befuddled Mr. Wisp haltingly extols his superior wife, describing her as powerful, Habakuk turns on him saying: “You might say—strong-minded woman—infidel—advocate of woman’s rights and free lover!”

Mrs. Wisp declares she “shall enter Paradise in Bloomer costume or stay out in the cold.” To which Habakuk replies

You need not burden your husband with the expense of another suit. Yours seems entirely fit for the place where infidels and free lovers are likely to go.

When confronted by Susan, his paramour, demanding he marry her, the insufferable hypocrite says:

Out upon you, sinful woman! I never promised you marriage. You led me astray—entrapped and seduced me, and turned me from my holy calling into the path of sinners. Go hence! The end draweth nigh!

At one point Mrs. Wisp, the Bloomers advocate, asserts:

But really, my sex has rights, and should be regarded as on an equality with men. Equality, in the estimation of the constitution—and before the law;—that is what we urge, and that is simply just.

Later, Mr. Fish gives proof of his sanity when asked by Habakuk if he knows “the end draweth nigh?”

No; but if such should be the case, I can’t say that I regret it. The introduction of man on this planet has not, I think, been a success—if common honesty or decent religion were the object in view; and the sooner the experiment ends, the better.

Habakuk, who might be understood to belong to a cult, doesn’t hesitate to vituperate the Mormons:

Then there was Joe Smith. He was a tavern-haunting horse jockey, and had for a boon companion a journeyman printer of some talent, but of dissolute habits, who had amused his leisure hours by writing a large amount of trash in imitation of the style of the Old Testament. The poor devil of a printer died, and Joe appropriated his manuscripts, and finally invented the story of the Revelation by means of golden plates, buried in the earth, containing the substance of the Mormon Bible. He printed this stuff and set up for a prophet, priest, and almost king, and had his claim allowed by the fools who flocked to his standard, and his disciples flourish at Salt Lake even unto today.

Throughout the play Wooden Nutmeg, described as “a Yankee—Conservator of the House, and busy-body in general who keeps a keen eye on the events that transpire.” He is a story teller and something of a dry wag. He is encouraged to demonstrate his ability to use an iron bar to defy gravity. He utters an incantation:

Hokey, pokey, larry-cum-bump;

Num-pum, rum-pum, thum-pum;

Tokay, rokay, jerry-me-jump;

Mum-pum. Sun-pum, bun-pum!

While intoning, he rigs the bar in order to make it look like it actually does defy gravity. He then conducts a séance for his gullible audience. Seances had become very popular during and after the Civil War as the bereaved hoped to contact their deceased loved ones. He evokes the voice of Jerusha, the late wife of Habakuk, who accuses him of having poisoned her. The good lawyer, Code, assists Nutmeg by providing Jerusha’s voice. “(the circle breaks up in wild confusion.)”

The good fortune of Fish appears to have magnified when oil is struck on the grounds of the Model House, but it soon turns to calamity when the gushing oil catches fire and the great house. is destroyed. Also destroyed is Mr. Fish’s entire fortune which was tied up in government bonds that were burned to ashes. The Fish family is forced into humble dwellings and live in penury. However reduced he finds himself, Mr. Fish remains philosophical and wonders at those who delight in the misfortunes of others. His good temper is rewarded when the faithful Code is able to convince the government to reissue his bonds, and he and his family are restored to prosperity. Likewise, Mrs. Fish has been restored to her sanity, although her grammar remains chaotic. They purchase a tidy cottage and move in. Mr. Fish is happy:

We are happy at last! And amid all the scenes which have we passed through, I have learned: that the largest mansion may shelter as much misery, and as much vice, as the meanest hovel; that extremes of grandeur and poverty are alike to be avoided; that a medium in houses, as in all things, is best; and that such a cottage as this, with such faithful and attached dependents as these (pointing to Tim, Cont. and Susan), for whom I hope I have provided to their heart’s content…is really and truly the Model House.

We have only skimmed the surface in describing the shibboleths that the author explores. Like Deseret Deserted, this is a competently written and structured play for which an author might well want to take credit. Possibly, the accumulation of attacks on some other peoples’ follies convinced him to lie low.

For more information about this digital resource, please contact Readex Marketing.