“Humbugs and fol-de-rols!”: Highlights from Nineteenth-Century American Drama

This final release of plays from Nineteenth-Century American Drama includes a devastating assault on Abraham Lincoln, an all-female cast in a courtroom drama meant to ridicule women, and a “Negro sketch in two scenes.”

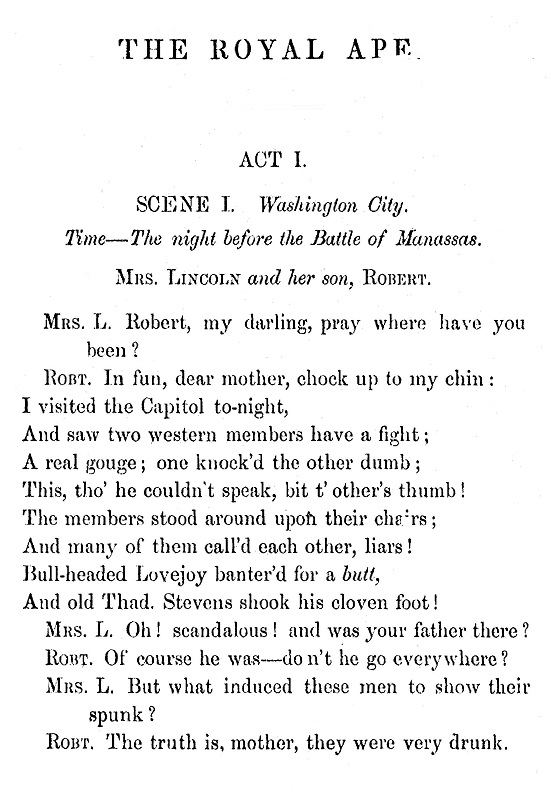

The Royal Ape. By William Russell Smith (1863)

William Russell Smith was a U.S. congressman from Alabama who served from 1851 to 1857. He subsequently served as a member of the first and second Confederate Congresses. Smith was not the first, nor the last, to describe Lincoln as a simian. He wrote this “dramatic poem” after the Union’s defeat in the Battle of Manassas as the South preferred to call what the North called the First Battle of Bull Run. It is dated January 1, 1863, in anticipation of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

Smith’s cast of characters—with the exception of two former slaves, two White House maids, and extras including officers, soldiers, citizens, and senators—are all prominent politicians and generals of the time. In following the action of the play, knowledge of the actual events of the time provides some perspective.

Act I, Scene I, occurs in the White House on the eve of the battle which Smith refers to as Manassas. We discover Mrs. Lincoln and her son Robert who would have been age 20. He has just returned from the House of Representatives and describes with gusto a physical fight that had broken out there.

He says that “Dad” with god-like authority commanded them to cease, and they heeded him. Mary sends Robert to bed, resolving to sit up to await her husband’s return.

I’ll wait awhile for Lincoln: he’s a bird,

To quell these tempests at a single word!

So all his actions do to greatness tend;

He always plays the hero to the end!

Happy Republic! Abram at the helm,

Rebels and rebeldom we’ll overwhelm.

Meanwhile we are treated to Robert’s multiple dalliances with the maids Kitty and Kate as he arranges to visit each alone later that night. President Lincoln arrives and wastes no time trying to seduce Kate by telling her he has dreamed of her.

LIN. No flattery at all; I tell you, Kate,

The dream revealed that I had lost my mate,

And some how, or some other how, it seemed

That, out of Heaven, your face upon me beam’d!

Kate, could you love me? [Takes her hand]

KATE: I already do.

There’s nobody I love as well as you! [Lincoln kisses her hand.]

My father taught me to revere gray hairs!

[Lincoln drops her hand and retires hastily.]

He’s very easy bluff’d! He takes a hint

Almost as easy as he takes a pint!

Thus is the president defined as a womanizer and a drunk.

Two prominent Northern politicos play important roles in the drama: Senator Henry Wilson, considered a Radical Republican, and Representative Alfred Ely of New York who was captured and imprisoned when he was a spectator at Bull Run. The author uses them first to make great claims about the triumph the Union will achieve at the battle, and later, as comic foils when they are captured together and encounter two slaves who rob them and betray them.

Smith’s classical references are evident in the soliloquies of the Southern generals in the battle.

BEAUREGARD: Gallant Virginians! your arms, to-day,

Will crowd the records of the old Dominion

With great historic deeds. Your names shall be

Themes for the songs of poets. Every rill

And valley shall be vocal with your praise;

For classic Greece, with all her battle fields—

Plataea, Leuctra, Mantinea—here

Beholds a sister worthy to be twin

With her in glory…

Smith uses Wilson and Ely to witness the battle, and their account grows increasingly alarmed as the battle turns toward rebel victory. As our hapless politicians flee, they are captured individually by Sambo and Hercules who, as stock representations of slaves, are ignorant yet sly. Having the slaves capture them is plausible. Having them be cheap characterizations is gratuitous yet fits the purpose of ridiculing the Yankees. Wilson tries to tell Sambo that he is his advocate, saying, “I bring you liberty and equality.”

Smith indulges himself, presenting scenes of errant celebration in the White House before the battle turned. When he wrote this “dramatic poem” in 1863, the Confederacy was in ascendancy. He seems smug. History disabused him. It is notable that Smith has Lincoln escape from Washington in a dress, presaging Jefferson Davis at the war’s end.

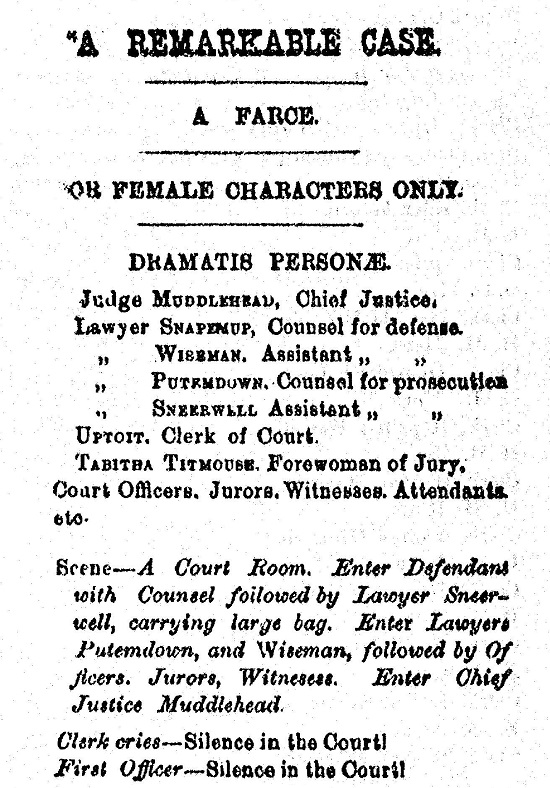

A Remarkable Case. A Farce in One Act ala Bardell vs. Pickwick.

For female characters only. By Stuyvesant [pseud.] (1899)

The setting is a courtroom.

Mrs. Wiseman reads the indictment:

Wiseman—(reading from paper) Know all women, by these presents, that Seraphina Standout is hereby arraigned, before this high and august Tribunal, for the high crime and misdemeanor, of openly defying and violating the Fashion Laws, passed in this city…[which] expressly forbids, any citizen of this free and enlightened country, to appear upon the public streets, dressed, or in any way accoutered, save as the said Fashion Laws do permit and allow.

She, the said Seraphina Standout, upon the seventh day of Febuary [sic], in the year 1897, was beheld upon the most public of the promenades of this city, attired in garments of strange and antique manufacture, whereas, the “Cut away Coat,” and kitted skirt, being the only robes allowed for street wear. She is hereby brought to trial by her outraged and insulted countrywomen. [Takes her seat.]

The remarks of Putemdown, counsel for the prosecution, are revealing. After bemoaning that never, in all her professional years, “have I stood up with so much indignation and grief, to plead a case. Despite Seraphina Standout having had every privilege and advantage, she “has repeatedly disregarded the laws made and passed by the wisest women in this country, and shown herself utterly indifferent to the fashion laws of the land.”

Can this have been the first arrest of the fashion police? It would seem that women are in charge of all of the wheels of power, and that one of their greatest interests is in policing their sisters’ fashions. It transpires that Standout, reprimanded by her parents and friends, refuses “to patronize the elegant and elaborate ‘Emporium of Madam Marabile’s Perfumed Perforated Paper Patterns’” Worse, “she declared the said Patterns to be ‘humbugs’ and ‘folderols’” The accused further will not do her hair as ordained nor wear French heels, nor adorn herself as dictated with bangle bracelets. Putemdown brings herself to tears and soon the jury, judge, and audience are weeping.

During the trial the lawyers and judge have several spats about procedure which would be flagrant violations of the norm but serve to further the misogyny that prevails throughout. Essentially, we are treated to a fight that demeans women. It is amusing that the author slips at least twice during Wiseman’s summation when she refers to counsel for the prosecution with masculine pronouns.

This farce is dated January 1899. In less than 20 years the first all-female jury in U.S. history was seated in Orange County, California, which had voted to permit women to serve in civil cases although they did not have the vote. They were selected by a public prosecutor in an obscenity case against a newspaper editor. The D.A. thought it was a clever ploy because women would naturally recoil at such depravity. They found the editor not guilty.

Unfortunately, for Standout things went the other way. The jury voted guilty “with a recommendation to mercy.” Judge Muddlehead was not moved. Seraphina was sentenced to “six months in solitary confinement.”

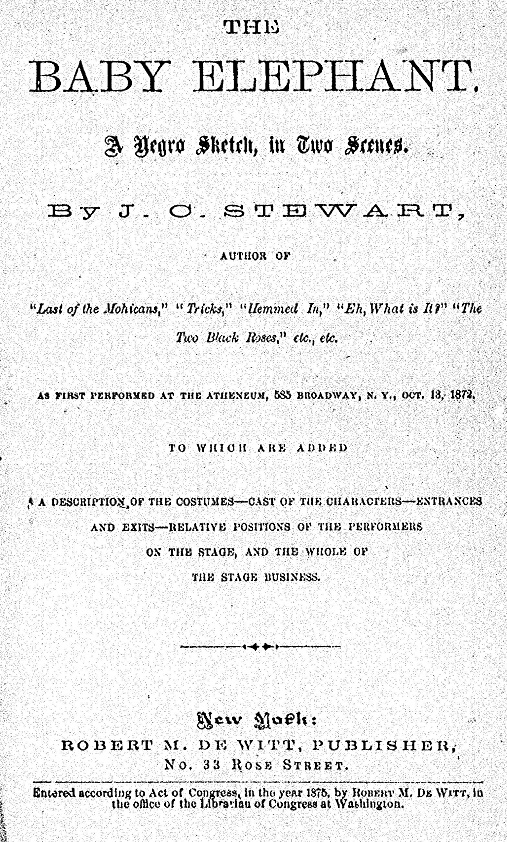

The Baby Elephant: A Negro Sketch in Two Scenes. By J. C. Stewart (1875)

J. C. Stewart was the pseudonym that, according to the Library of Congress, was used by “John Stewart Crossy and his son John Hart Crossy, two rotund vaudeville actors who looked very much alike…”

“The Baby Elephant” is a minstrel play distinguished by its two black characters Cuff and Pete who are comic foils. One of the main characters is called Barnum and is clearly based on the real P. T. Barnum who had a number of setbacks in his career as a showman. As the play opens Rifle, a frustrated suitor for the hand of Mr. Growler’s daughter Rose, and his servant Smithers are plotting another attempt to breech the walls of the Growler house. As they exit Barnum enters and soliloquizes.

BARNUM. Was there ever a man in this world in such hard luck as I am? I’ve been in all sorts of speculations, from manager of a first class menagerie to a cork burner of a minstrel show. No matter what I undertake, I fail in everything. My last speculation was that of a Headless Rooster. I’d have got along first rate if it hadn’t been for Bergh, who had me arrested for cruelty to animals; and this morning, to add to my troubles, my landlady informed me if I didn’t pay my rent I’d have to leave. I’ve not tasted food for 24 hours. Oh! What would I not give for a good square meal?

Growler has been wise to the subterfuges employed by Rifle using Smithers as his clandestine agent. More than once he has ejected Smithers from his house. Barnum witnesses one such ouster and hears Growler expostulate. He proposes to Rifle a scheme to dupe Growler and gain access to the house. Growler is known for keeping a menagerie, which includes a bear, and to be avid for more wildlife acquisitions. Barnum claims to have a baby elephant sequestered nearby and will produce it for $500.

The baby elephant is, in fact, a two-person elephant suit. Fortunately, Growler has lost his glasses and is nearly blind without them.

Much confusion ensues as Rifle, disguised, and Barnum enter the house. Barnum conducts business with Growler, they leave, and they return. This time Rifle and Smithers are wearing the elephant costume. Barnum has the elephant do tricks for Growler. Cuff and Pete get completely twisted up in the proceedings to no good end.

Soon, the two servants set Growler wise to the deceit. Growler demands to know if Rifle was the front or rear of the costume. Upon determining that Smithers was the rear end and therefore must have been the one who kicked him earlier, he offers 25 dollars to anybody who finds him. The final stage directions conclude the play:

(All look round for Smithers, who is discovered sitting in one of the upper stage boxes. They tell him to come down and he refuses. Growler calls Policeman on stage, and tells him he’ll give him $25 to bring that fellow out of the box. Policeman calls him down, and he refuses. Policeman goes up to box and is discovered fighting with Smithers in box. Excitement kept up on stage. Policeman slips out of sight; Smithers throws Dummy Policeman out of box on to the stage. They pick him up quick and rush up the stage with him and fan him, etc.) Quick Curtain.

To learn more about Nineteenth-Century American Drama, which is now complete, please contact Readex Marketing.