“I tell what I have seen”: Treatment of the Mentally Ill in Early America

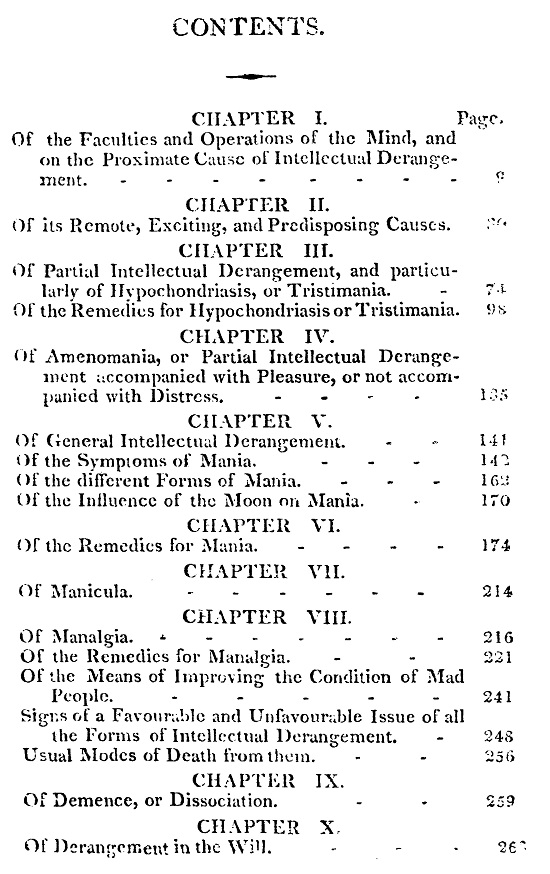

The history of enlightened treatment of the mentally ill in the United States was significantly affected by Dr. Benjamin Rush, the famed Philadelphia physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence. In 1812 he published Medical Inquiries and Observations, upon the Diseases of the Mind in which he presented his ideas “with a hope that they may serve as a supplement to materials already collected, from which a system of principles may be formed that shall lead to general success in the treatment of the diseases of the mind.” He further wrote: “…the author believes those diseases can be brought under the dominion of medicine, only by just theories of their seats and proximate cause.” The first page of the table of contents evidences the breadth of his knowledge.

In 1814 another of the country’s most eminent physicians, George Parkman of Boston, published his ideas for enlightened care in a volume titled Proposals for Establishing a Retreat for the Insane. Parkman concurred with Rush that mentally ill people were more likely to improve when they were domiciled in a good physical environment free from cruel treatment.

The arrangement of the house will resemble, as much as possible, that of a private residence, affording as many enjoyments of social life, as the circumstances of each patient may allow…[and] will be courteously received at the Retreat, as a stranger, and he will not discover that his misfortune is known there, until maniacal extravagance demands his restraint.

Enlightened thinkers were opposed to harsh treatment of the mentally ill, including physical restraint except to prevent injury, but realized the necessity of strategies to avoid agitating patients.

This Institution will aim to avoid every thing [sic], which can excite or aggravate the fury or sadness of the patients; to appear not to notice their extravagances; to yield to their caprices, with apparent complacency; to elude with dexterity their inconsiderate demands….

Thomas Eddy was a successful financier in New York City and a man known for his extensive philanthropy. After working on prison reform and construction of a free hospital for the poor, he turned his interest toward founding an asylum for the insane. In 1815 he published Hints for Introducing an Improved Mode of Treating the Insane in an Asylum in which he applauded progress in discarding the popular idea that treatment of the mentally ill which “appears to be, that of considering mania a physical or bodily disease, and adopting for its removal merely physical remedies.”

Eddy had become persuaded that “moral management,” often referred to as moral treatment, was the enlightened way to proceed. The concept of this humane approach had been put into brick-and-mortar practice by Quakers in Yorkshire, England, in 1796 under the leadership of William Tuke with the founding of the Yorkshire Retreat. Eddy, too, was a Quaker, and his “Hints” were directly responsible for the establishment of New York’s Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in 1821.

The most effective advocate for moral treatment and the establishment of asylums designed to facilitate it was Dorothea Dix. Her reforming campaign encompassed prisons and the management of military hospitals during the American Civil War. In 1843 Dix submitted a memorial to the Massachusetts legislature which starkly described the conditions in which mentally afflicted persons subsided in that state.

But truth is the highest consideration. I tell what I have seen—painful and shocking as the details often are—that from them you may feel more deeply the imperative obligation which lies upon you….Gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of Insane Persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience!

While many physicians concerned themselves with the classification of the various manifestations of mental illness, others, including Dr. Edward Jarvis, were equally concerned with determining the causes. In 1851 Jarvis addressed a medical society in Massachusetts regarding his research on this subject. In his published remarks Jarvis divided the causes among “physical cases,” which included diseases and injuries, and moral causes. The former included fever, sexual derangement, diseases of the uterus, exposure to noxious vapors, mesmerism, and tight lacing [presumably of some women’s underclothing], while the latter included religious anxiety, unrequited love, reading vile books, and ungoverned passion. He argued that “In many cases of insanity, there are several causes, or precedent facts that may be assumed as causes, of the derangement.”

To illustrate his theory, he wrote

And it is not uncommon for two or more events or facts, that are here enumerated as causes, to have happened to a lunatic previous to his disease. As a student excessively engaged in study is also dyspeptic, and then becomes insane, and he not unfrequently adds masturbation to these causes of mental disturbance. An intemperate man very frequently manages his affairs indiscreetly, and becomes embarrassed or poor; or if he holds a public office he loses it, and is therefore disappointed. Either or all of these may be assumed as the cause or causes of the mental disorder.

As the number of asylums increased so did issues of patient classification, especially as concerned those considered curable and those that were not. It was argued that comingling patients regarded as curable with incurable patients harmed the formers’ possibility of restoration. Dr. Pliny Earle had been attending physician at several prominent U.S. asylums and had twice toured European hospitals for the insane before becoming superintendent of the state hospital in Northampton, Massachusetts. In 1868, he published Prospective Provision for the Insane which addressed the issue of separation of patients about which he concluded

I approve of large hospitals, those which accommodate from three hundred to five hundred patients, as the best practicable plan for the care of all the insane who must be congregated. This plan I would pursue so long as the number of incurables is not largely disproportionate to that of curables.

If the incurables were too numerous, Earle wrote, he “would adopt that style of institution which unites the characteristics of both the hospital and the colony. The principle building should be a hospital commensurate in its perfection with the knowledge of the time.”

In 1885 Frederick Howard Wines published Provision for the Insane in the United States: A Historical Sketch in which he limned the issue of the poor who suffered chronic mental illness. He cited at length the writings of Dr. Isaac Ray “who was, at the time of his death, in 1881, the acknowledged Nestor of the fraternity of superintendents.” Ray recounted efforts to provide for

the proper care and custody of the old incurable cases. It was their sufferings, as exhibited in the jails and poorhouses of the country, which, some five and thirty years ago, led Horace Mann and a few others to begin that movement, the first fruits of which were the hospital at Worcester, Massachusetts….For a time it seemed as if the precise object of their labors had been accomplished and placed beyond the reach of any change of fortune. The jails and poorhouses were emptied of their unfortunates, and an incalculable amount of relief from the last extremity of human wretchedness was effected.

However, by 1866 Ray asserted that

the conclusion has been generally adopted, that if any are to be excluded from the hospital, for lack of room, it should be those to whom it would be a permanent home, rather than those for whom a few months’ residence would lead to recovery or considerable improvement….The patients thus discharged, after exhausting, perhaps, the patience and the bounty of their friends, arrive, sooner or later, at a final home in the poorhouse or jail, and thus steadily increase that mass of suffering humanity whose dimensions seem to defy all resources of public benevolence.

Dr. Richard J. Dunglison published Statistics of Insanity in the United States in 1860. The doctor stated that

The institutions devoted to the care and comfort of the blind, deaf-mute, and insane portions of the population, do not appear equally to appreciate the value of general information upon points on which professional and unprofessional are eager to acquire knowledge.

He complained that too often people are told

as if they were almost the only points which could possess any interest to us, that the institution has expended so much in the course of the year for groceries and provisions, and has laid out its grounds in such a scientific and ornamental style of gardening as to excite the admiration of all beholders!

Rather than this sort of information, he argues that more important is “an enumeration of all the facts bearing upon the causes of predisposition to certain morbid affections of the senses, a personal history of the patient’s condition, sex, and age…” and more “through which lessons may be learned to guard us from the incursion of disease, or to assist us in relieving the infirmities to which we are subject.”

Dunglison relied on the annual reports issued by asylums to garner his data. An example of these reports was issued by the Longview Asylum in Ohio in 1866.

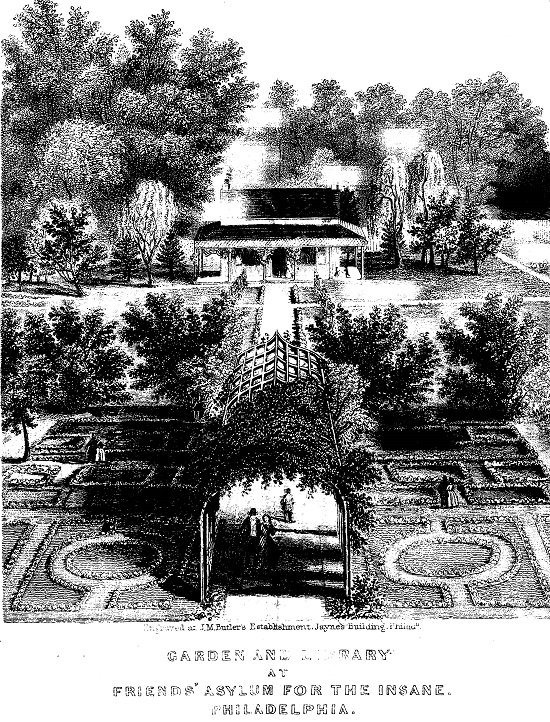

Another, later report, 1869, was issued by the Asylum for the Relief of Persons Deprived of the Use of Their Reason (Friends Asylum for the Insane). The report provides tables of data as was desired by Dunglison. The various causes of the patients’ illnesses include loss of property, excitement about religion, grief, disappointment, and anxiety. Additionally, the superintendent described the physical condition of the institution and provided examples of success in restoring patients to their senses. The managers reported on the finances and explained the process of admission to the asylum which was “open for the reception of all classes of the Insane, without regard to the duration or curability of the disease. It is proper to state, however, that idiots or persons affected with mania-a-potu are not considered suitable subjects for this Asylum.” Mania-a-potu is generally defined as insanity caused by excessive alcohol use—vide delirium tremens.

The enlightened beliefs of the early 19th century led to the construction of asylums where patients were treated with dignity in appropriate settings, to the classification of the manifestations of mental illness, to the development of an understanding of the causes of these maladies, and the application of these endeavors to better, more effective treatment.

Learn more about Readex products, including Early American Imprints and American Pamphlets.