"Appeal to Loyal Women!" -- The Creation of the United States Sanitary Commission and the Impact of Civilian Volunteers during the American Civil War

Henry Whitney Bellows (1814-1882), planner and president of the United States Sanitary Commission, the leading soldiers' aid society, during the American Civil War.

On April 12, 1861, Confederate artillery opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. The first shots had been fired in a war that would last four long and bloody years. This April marked the beginning of a four-year commemoration of the 150th anniversary, or Sesquicentennial,of the American Civil War. Over the next four years, Civil War re-enactors, historians and history enthusiasts from across the United States will gather to help commemorate the battles and other important events linked to the war.

With the start of the Civil War in 1861, hundreds of aid societies sprang up across the country almost as quickly as young men rushed to enlist. Women of course were barred from enlisting in the military, although a few successfully disguised themselves as men and joined the fight. In New York, a group of women wishing to show their loyalty and patriotic spirit formed the Women's Central Association of Relief, inspired by the work of Florence Nightingale and the British Sanitary Commission during the Crimean War. However, efforts to gain government support for their organization proved unsuccessful until Dr. Henry WhitneyBellows stepped in to help. Dr. Bellows and a group of male doctors traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet with President Abraham Lincoln on behalf of the women's organization. At first, the president and other government officials were reluctant to have civilians become involved with the needs of the military. In spite of this, the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) was established on June 9, 1861, with Dr. Bellows as its president.

"United States Sanitary Commission. Our Heroes." Source: Harper's Weekly. Courtesy: Brooklyn Museum Libraries

The headquarters of the USSC was in Washington, D.C., but regional commission branches were established throughout the Northern states, most notably in Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia. These branches acted as collection and distribution centers. Individuals and local aid societies shipped boxes of supplies to the commission branches where they were repackaged for delivery to soldiers in the field. Money was also collected and used to purchase additional food, clothing, and medical supplies.

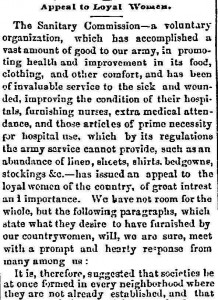

From the Jamestown Journal (NY), Oct. 18, 1861. Source: America's Historical Newspapers

By 1863, there were nearly 7,000 local aid societies affiliated with the USSC. Knitted socks, linens for bandages, quilts, baked goods, writing paper, stamps, and medicines were just a few of the many items that poured in. Even the little town of Chester, Vermont sent items, as reported in The Vermont Phoenix on May 7, 1863:

The Chester Soldiers’ Aid Society was organized in October of 1862. We very soon decided that the Sanitary Commission was the best channel through which to send our supplies and accordingly sent our first box to the care of “The Womans Central Relief Association, New York. Nine boxes have been sent there—three to the Vt. 4th Regiment and one to Brattleboro Hospital....The following is a list of articles sent: 107 quilts, 509 towels, 233 prs. Socks, 27 flannel shirts and under shirts, 9 woolen blankets, 147 shirts, 22 pillows, 102 sheets, 232 prs. drawers, 86 pillow cases, 212 handkerchiefs, 24 cushions, 239 napkins, 14 cans currant and apple jelly, 41 prs. Slippers, 43 bed sacks, 10 dressing gowns, 6 bottles raspberry shrub, 78 lbs. dried apple, 12 lbs. currants, 3 bottles lemon syrup.

I was pleased to learn that my hometown of Springfield, Vermont also contributed to the war effort—as seen in this Nov. 9, 1861 item in the Springfield Weekly Republican:

“Springfield has done most excellently well in the war thus far. The town contains but 3000 inhabitants, yet has sent 80 men to fight for the country, five being from one family. The ladies also, during the three weeks just past, have manufactured articles for the sanitary commission, and have sent off five large boxes, containing the following articles: 46 bed quilts, 32 woolen blankets, 120 pairs of woolen socks, 111 pillow cases, 7 linen sheets, 43 cotton sheets, 67 napkins, 27 old linen handkerchiefs, 84 books and magazines, 5 old shirts, 2 cravats, 1 muffler, 1 dressing gown, 1 bag mutton tallow, 25 pounds dried apples, 3 boxes guava jelly, one can solidified milk, a quantity of cotton batting, and a quantity of old linen and cotton for bandages and compresses. Other articles have been handed in since the articles named were forwarded, and another box is to be sent soon.”

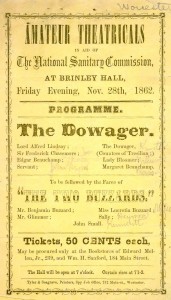

“Amateur theatricals in aid of The National Sanitary Commission, at Brinley Hall ... Nov. 28, 1862. Programme.” Source: American Broadsides and Ephemera

To help raise money for the USSC, fundraisers held sanitary fairs, bazaars, concerts, raffles, and plays. Play bills and concert programs for these charitable events are among the many USSC-related items found in America’s Historical Imprints. During its existence the USSC raised roughly $5 million in money and $15 million in donated supplies for the Union Army. The Western Sanitary Commission and the United States Christian Commission also supported the Union Army but worked separately from the USSC. The Confederate States had small aid societies, but none as large as the USSC.

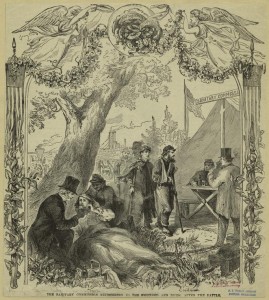

The USSC relied heavily on volunteers. Only a handful of individuals, mostly men, held paid positions. Sanitary agents were employed to inspect the living conditions of military camps and hospitals as well as the health of the soldiers, much to the disgust and annoyance of some military officers and surgeons. These agents would make note of any needed supplies, especially for sick or wounded men, and advise the officers on how to request such supplies from the USSC. Mary A. Livermore was one of the few paid female agents. Livermore and women like Clara Barton and Dorothea Dix, the Union's Superintendent of Female Nurses, were instrumental in organizing aid societies, collecting goods and money, and recruiting qualified nurses to work in the hospitals. In response to the flood of letters inquiring about wounded or missing soldiers, the USSC created a hospital directory. By April of 1863, the directory included the names of wounded or sick soldiers in every general hospital. Time and again the USSC proved its worth by providing aid when it was needed most. In many cases the organization was the first to provide medical care and supplies after major battles. Aid delivered after the battles of Fredericksburg, Antietam, and Gettysburg, for example, stands as a testament to the hard work and devotion of thousands of civilian volunteers. The USSC was also able to provide some relief to Union soldiers held at the infamous Andersonville Prison.

"The Sanitary Commission ministering to the wounded and dying after the battle." Courtesy: New York Public Library Digital Gallery

Although the Civil War ended in April, 1865, relief work continued for several months. The USSC aided soldiers and their families by providing food, lodging, and occasionally, travel expenses for returning veterans. Volunteers helped fill out pension claims, locate missing soldiers, and identify the graves of thousands of unknown soldiers. In 1866, the organization was officially disbanded. Work with the USSC opened many doors for women in the field of medicine and helped to convince people that women were capable of achieving great things. In 1881, Clara Barton helped found the American Red Cross using the United States Sanitary Commission as a model.

From the Oregonian, May 22, 1917. Source: America's Historical Newspapers

For more information about Readex collections, or to request a trial for your institution, please contact readexmarketing@readex.com.