“Bad roads, high waters, and various accidents”: The First Decades of the United States Postal Service

Before the American Revolution, postal service, such as it was, was administered by the British. Mail within the colonies was sparse, while the preponderance of mail was between North America and Great Britain. Benjamin Franklin was postmaster of Philadelphia when, in 1753, he became one of the two postmasters general in the colonies. He was dismissed in 1774 because of his political activity. However, in 1775 the Continental Congress appointed him Postmaster General of the United Colonies.

The founders realized that an effective postal service, including the establishment of postal roads, was essential to the coherence of the former colonies and expanding territories. The western expansion of the new Americans dictated the necessity of expanding the infrastructure. No longer was the Atlantic mail to and from Great Britain the main concern. Interstate and territorial mails required constant attention and expenditures.

In 1790 Congress enacted “a bill for regulating the Post-Office of the United States.” Periodically, for the next two centuries that act would be amended and rewritten in response to evolving circumstances.

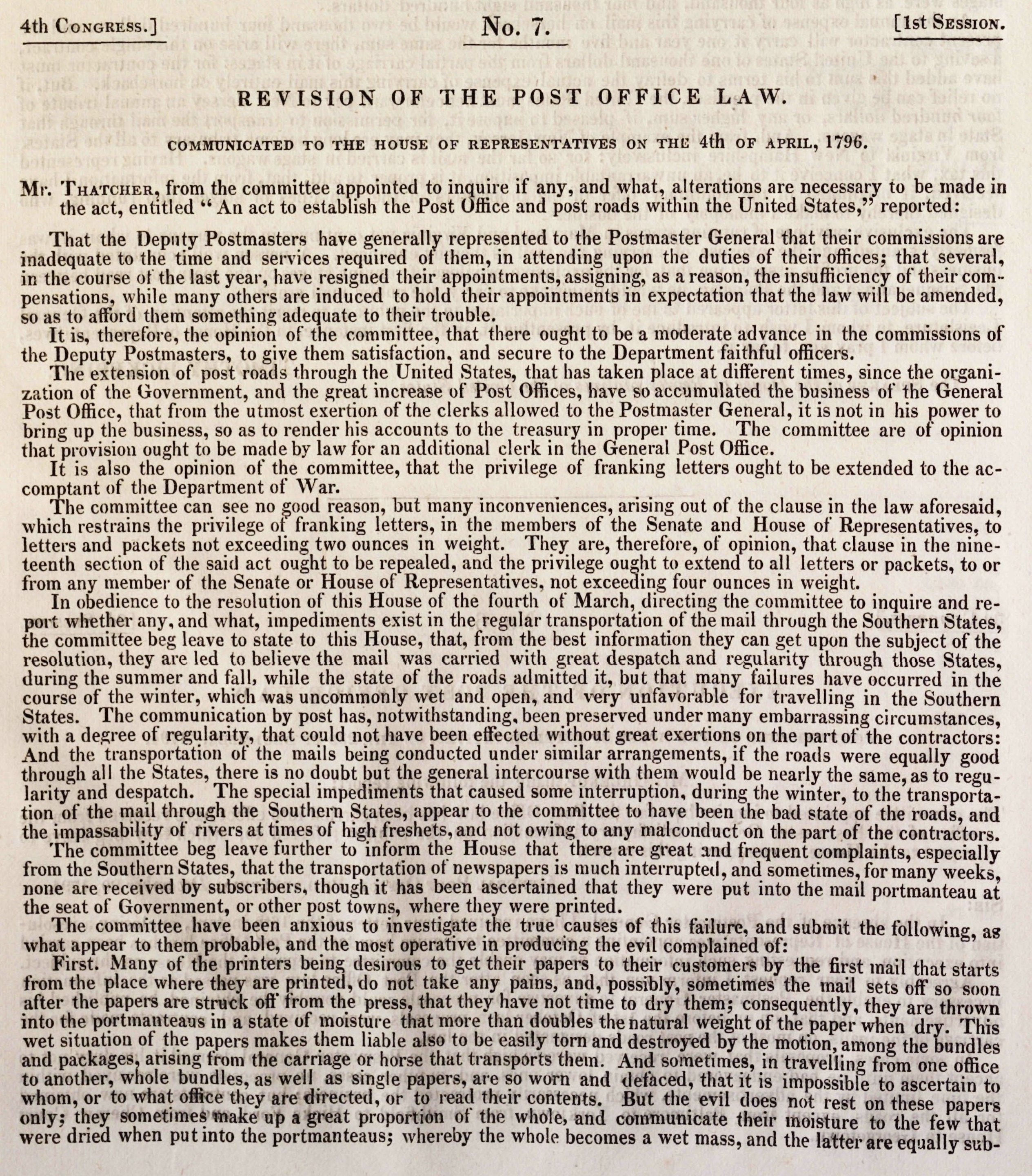

An example of the revisions of the Post Office law was “communicated to the House of Representatives on the 4th of April, 1796.” The alterations proposed included raising the pay of Deputy Postmasters whose “commissions are inadequate to the time and services required of them, in attending upon the duties of their offices…” Further, the amendments were concerned with the increasing demands on the General Post Office because

The extension of post roads through the United States, that has taken place at different times, since the organization of the Government, and the great increase of Post Offices, have so accumulated the business of the General Post Office, that from the utmost exertion of the clerks allowed to the Postmaster General, it is not in his power to bring up the business, so as to render his accounts to the treasury in proper time. The committee are of opinion that provision ought to be made by law for an additional clerk in the General Post Office.

Other matters involved franking [free postage for certain officials or elected persons], post roads in the Southern states, and the transportation of newspapers.

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 presented the postal service with new challenges. A letter to his friend Thomas Jefferson written by Isaac Briggs on the “22d of the 12th month, 1804” illuminates the difficulties he encountered surveying the route from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans. Briggs was a surveyor and engineer whom Jefferson had appointed to carry out this task. In addition to a debilitating illness which brought him “to the very verge of death,” Briggs explains the complexity of measuring longitude with his insubstantial instrument which prevented him from achieving his goal of pinpointing the locations of many geographical points.

Thus my chances of disappointment were multiplied beyond almost beyond calculation. I was therefore soon reduced to the alternative of relinquishing the idea of ascertaining the position of any but the most important places, or of protracting my report far beyond the proper period.

He settled for establishing a route with attention to eight specific towns and geographical features “leaving them to be connected hereafter by an actual survey, under the direction of a good judge.”

Other problems plagued the postal service because of westward expansion. Brick-and-mortar post offices were uncommon in the early 19th century. Typically, a contracted mail carrier delivered the mail to a particular person or establishment in a community who was charged with its timely and accurate delivery. Over time these individuals were named Postmasters. Their job included establishing an adequate physical space for executing their duties.

In 1818 a “resolution to inquire into the expediency of establishing in one of the Western States a branch of the General Post Office, for the purpose of making contracts for the conveyance of the mail, and to correct abuses in that Department” was submitted to the House Committee of Post Offices and Post Roads. The chairman reported on behalf of the committee.

That, in an establishment of such extent as that of the General Post Office of the United States, it is not to be expected that the most perfect system of responsibility, executed with the most untiring vigilance, could at all times secure the public from every species of irregularity and abuse; and when it is considered how many persons are employed as Postmasters, whose emoluments offer no inducement to a diligent attention to their duties in the appointment of whom in sparse settlements there is often not an alternative in the choice; and also that the rapid extension of the post routes requires, annually, the employment of untried mail carriers, whose want of experience or capacity, and the frequent interruptions from bad roads, high waters, and various accidents to which such undertakings are always liable, cannot fail to occasion irregularities in the progress of the mails. It is a matter of gratulation and surprise that so few interruptions and losses are experienced.

The committee’s resolution appears to sweep beyond the Western states: “Resolved, That it is inexpedient to establish a branch of the General Post Office in any part of the United States.”

Violence perpetrated against mail carriers and robberies presented another challenge. In 1806 Congress received a claim on behalf of a carrier who, according to the Postmaster at Fort Stoddert/Stoddard [Mississippi Territory, now Alabama],

was shot through the body, when carrying the mail in the Creek nation, on the 18th of August last, is now at this place unable to get out of his bed, with his wound so bad as to render it very doubtful whether he will recover or not. He has no friends in this country and no means of sustenance. The Indians brought him, by water, to this place; and, as he had been disabled when carrying the mail, he looks to me for support.

The House Committee of Claims “to whom was referred the petition of Josiah H. Webb, made the following report.” The report concludes “That the prayer of the petition is reasonable, and ought to be granted.” In arriving at their resolution the committee reasoned

when it is considered that the petitioner is now within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Government of the United States, in a part of the country where no regulations are yet adopted for the support of the poor; that he is under the immediate charge of an officer of the Government, who must either permit the petitioner to suffer for want of the necessaries of life, or maintain him at his own private expense, there can be little doubt that it is the duty of the National Legislature to extend its aid to an individual thus circumstanced.

For many years the General Post Office was in receipt of petitions and memorials protesting the movement or delivery of mail on Sundays. The relevance of this issue to an effective system of postal delivery was significant. The system depended on an increasingly complex schedule of transportation, sorting, and delivery. If all activities were to be suspended on Sundays, the result would be highly disruptive. For years these petitions arrived on a regular basis, and for years Postmasters General and various Congressional committee chairmen refused the petitioners but were careful not to be offensive.

On January 20, 1815, John Rhea of the House Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads stated on behalf of the committee

That they have had the same [petition] under consideration, and deeming it of great national importance, particularly in time of war, that no delay should attend the transportation of the mail, they deem it inexpedient to interfere with the present arrangement of the Post Office establishment, and, therefore, submit the following resolution: Resolved, That it is inexpedient to grant the prayer of the petitioners.”

The document includes a letter from the Postmaster General, Return J. Meigs, which concludes

that although public policy, pure morality, and undefiled religion, combine in favor of a due observance of the Sabbath. Nevertheless, a nation owes to itself an exercise of the means adapted to its own preservation, and for the continuance of those very blessings which flow from such observance; and the nation must sometimes operate, by a few of its agents, even on the Sabbath; and such operation may, as in time of war, become indispensable; so that the many may enjoy an uninterrupted exercise of religion in quietude and in safety.

Seldom, if ever, in the repeated refusals to suspend all Sunday postal service was the issue the separation of church and state.

Frequently, Congress was presented with bills “to alter and Establish Certain Post Roads.” An example is found in a typical bill authored in 1815 which included termination of certain routes. The place names are evocative:

…the following post roads be, and the same are hereby discontinued, that is to say: From Shelbyville, by Winchester, to Fayetteville, in Tennessee. From Tellicoe, in Tennessee, by Amoy river, Vanstown, and Tuckeytown, to Fort Stoddart, in Mississippi territory; and from Tuckabatchy, by Tensaw and Fort Stoddart, to Pascagoola river, in Mississippi territory.

Roads were discontinued if the revenues were overwhelmed by the expenses. However, many more routes were being established than terminated. The 1815 bill proposed new postal roads in 15 states including New York:

From Hadley Landing, in Saratoga, to Luzern, in Warren county. From Hamilton Village, on the route from Albany to Cherry Valley, by Guilderland, Berne, Schoharie court house, the Dutch church, in Middleburg, the brick church, in Cobleskill, col. I. Steward’s, Maryland, and Milford, to Unadilla. From West Point to Haverstraw. From Plumage Mills in Coventry, to Oxford. That the mail from Huntington be carried by the north road to Smithtown, instead of the south road. From Stillwater, by Dunning street, in Malta, and the south end of Saratoga Lake, to Ballston Springs, thence by the north end of Saratoga Lake, and by Rogers’ mill to Stillwater.

This is a distance of approximately twenty-five miles which illustrates the complexity of laying out routes.

The safety of the mail and the mail carriers was a growing concern as attacks and robberies became more common. On February 16, 1819, the Postmaster General sent a letter to the chairman of the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads concerning “authorizing the Postmaster General to employ an armed guard, for the protection of the mails of the United States on such mail routes as he may deem necessary.” The Postmaster General threw cold water on the idea because of the expense and the potential perfidy of some guards:

…it will be impossible for the pecuniary receipts of the Department, to defray the expenses on any considerable portion of the stage routes alone, on which stages run more than 10,000 miles per day; even the stage fare of the guards would be very expensive. The qualifications of such guards should be fidelity, vigilance, and courage, for the use of which, they have always demanded and received high compensation.

On the complete exercise of those qualifications, would depend the whole security of the mail, as the guard would possess a complete power over the mail carrier, and the mail; and if unfaithful, might effect the most extensive depredations on its contents….If the system of employing armed guards be once adopted, it could never with safety be abandoned…

A little more than a month later, a carrier was murdered:

The Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads, having been instructed, by a resolution of this House, to inquire into the expediency of affording some pecuniary relief to the widow of John Heaps, late of the city of Baltimore, deceased, reported:

That the said John Heaps, on the 24th day of March last past, being employed as a carrier of the United States mail, and having the said mail in his custody, was beset by ruffians, who murdered him and carried away the mail; that the said John Heaps appears to have sustained a good character, and died leaving a widow and two children under six years of age, all in indigent circumstances, and proper objects of charity.

The problem of increasing postal robberies grew sufficiently to prompt Congress to act. On March 18, 1822, the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads, issued a report which read, in part:

That they consider the safe transportation of the public mails a desideratum of the utmost importance, and that the robberies of late is matter of serious regret and alarm, calling imperatively for a corrective.

They described

a new plan invented by Richard Imlay, by which it is proposed to substitute for the leathern bags now in use, copper cases, secured in iron chests, by inside locks, and sliding bars, in such a manner as to render it extremely difficult, and, in the opinion of the committee, necessarily a work of several hours to effect a robbery, and which in no case can be done without much hammering and noise.

ranking privileges, essentially free postage, were originally established by the House of Commons in the 1600s. The First Continental Congress established franking privileges in 1775. In 1789 Congress established it as law and it was extended to include members of Congress, the President and Cabinet, and certain officials in the executive branch. It also included newspaper publishers who could send a franked copy of each issue to every other American newspaper.

However, throughout the 19th century this privilege was challenged, abolished, reinstated, and altered. On March 17, 1826, the Postmaster General wrote a letter to Congress concerning its abolishment. He warned that

Considering the very great importance of the duties performed by Post Masters, their confidential nature, and their great value to the public, it is conceived that no officers under the Government are more penuriously paid for their services than a great majority of them are, and if the privilege should be withdrawn, it is believed that the pecuniary addition, which would be required, to the amount of money they now receive, in order to bring up their compensation to a level in their estimation, with its present value, would embarrass the operations, impede the utility, and probably exceed the means of the Department.

It will hardly be necessary after this comparative view of the subject, to say that I consider the abolition of the privilege at present inexpedient.

The compelling necessity of expanding the postal service and postal roads continued to challenge the Post Office department and Congress. The advent of railroads began a period of expanding the use of rail services to move the mails. In 1837 the Alexandria and Falmouth Railroad Company petitioned Congress for financial aid toward the cost of construction. They argued that

No power exerted on a common road can compete with steam upon a railroad. Failures would be rare upon a well-constructed and well-conducted railroad. So that the Post Office Department must either be content to see the public mails left far behind in the race, or submit to the exactions of these corporations.

The task of maintaining an effective, economical postal service that would meet the needs and expectations of an expanding public was a constant goal of Congress during the Early Republic. The service had to be sure-footed and responsive to dynamic changes in the distribution of the American population.