Bicycle Face: ‘It Is Sound Physiology, and It Squares with the Facts’: Following a Phrase in American Historical Newspapers

The 1880s saw the modern bicycle, with a diamond frame, pneumatic tires, and a chain-driven rear wheel, take shape. Along with their similarly sized wheels, these features made the new machine safer than most existing velocipedes and earned it the nickname ‘safety’.

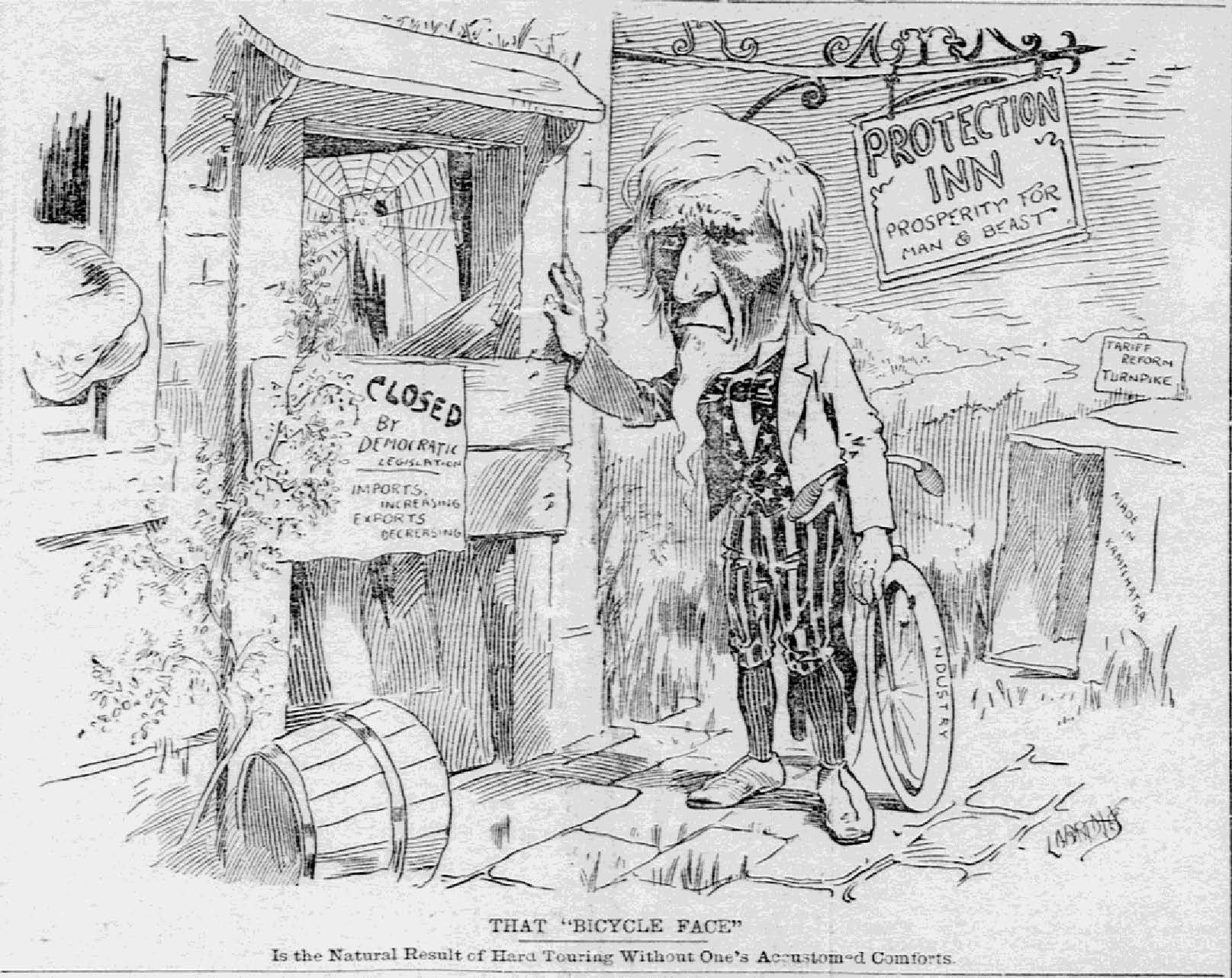

However, the new technology was not without consequence. As the safety gained popularity an as yet unrecognized ailment started afflicting many wheelmen. The first reference in America’s Historical Newspapers to the term ‘bicycle face’ dates back to the summer of 1895.

On July 4, 1895, The Boston Daily Advertiser quoted a “physician, writing in the St. James’ Budget” describing the phenomena:

They frequently wear an anxious look and an unwholesome pallor, which are so characteristic that one may almost speak of the “bicycle face.” Watch them descend at an inn, a good many exhibit anything but the exhilaration of the healthy exercise. Some are more than pale, their faces have the peculiar gray hue which betokens nervous exhaustion. And they complain of headache – a singular complaint for young men engaged in an athletic pastime. This is true of so many as to be quite noticeable, and to make people ask why bicyclists always “look so seedy.”

The doctor continues, explaining the source of the problem as being the exertions required of a rider to maintain their equilibrium.

“Learning” to ride means mastering the art of keeping the machine upright. It has a tendency to fall to one side or the other all the time, which has to be counteracted by a special effort. The learner knows it very well to his cost, but once having learned he forgets about it and does his balancing more or less automatically. Nevertheless the effort is still there and puts a constant though unconscious effort upon the brain and nervous system. The reason why the bicycle has to be “learned” at all is that the centre of equilibrium in the brain requires to be taught the business of doing its duty under novel circumstances. The falling bicycle is maintained upright by a constant series of small muscular movements, which unconsciously adjust the weight in the proper position, and are themselves controlled by a special brain centre situated at the back of the head. The strain upon this centre is incessant, though unmarked, and some people cannot stand it for more than a shore time.

Two days later, The Minneapolis Journal printed a similar article about ‘bicycle face’ and the nervous strain of maintaining one’s equilibrium. It also noted some riders may be unafflicted, positing “probably it does not affect those who begin very young, and possibly it affects those with either very tough or very dull nerves but little.” The report, however, concludes:

Most of us, however, are obliged to live in such a way that our nervous systems become very susceptible to any unaccustomed strain, and those who are most likely to use the bicycle belong to the most susceptible classes. The nervous effort entailed by balancing the machine is too much for them. The explanation may strike some people as fantastic, but it is sound physiology, and it squares with the facts. Experienced cyclists often say that the tricycle, and even the old high bicycle – which requires less effort to balance – are less fatiguing for prolonged work, such as a tour, than the safety; yet the latter is lighter, quicker and superior in nearly every respect, save that of stability. It is a question of balance. Wheeling is not a pursuit that will suit everybody.

An item in The Boston Herald offered additional confirmation of the supposed malady but suggested it was older, in fact, than was suspected.

The theme is not a new one, and was noticed in “Pounce & Co.” as far back as 1882 when one of the characters in the opera was made to say: “When I see a daring rider mounted on his fiery bicycle, speeding on his jolting way over uneven roads, I envy him the exquisite illusion that he is enjoying himself. Such touching beliefs in the impossible are, alas, too rare. How hopelessly sad he looks. A bicycle rider has never been seen to smile while urging his wheel on its way. There must be some hidden mystery, some deep heart anguish that impels him to that species of exercise as a solemn penance.” It is still the same face.

Others offered a different explanation altogether; disregarding age, nerves, whether tough or dull, and even the act of riding itself. On July 8, The Daily Inter Ocean printed this ‘Letter to the Editor’:

You and the philosophers are at sea. “Bicycle face” is not produced by bicycle riding, but is due to the persistent mastication of chewing gum. Technically it may be described as muscular paralysis. Why bicycle riders should contract the chewing-gum habit is beyond my comprehension. – An Ex-M.D.[9]

In the face of such dissention the obvious solution was to turn to science. On July 19, 1895, The Kansas City Times did just that, only to find a further divergence of opinions. “And Now the Bicycle Face: Scientists Disagree as To the Cause of It,” reported:

The bicycle face is the discovery of a doctor who rides the bicycle with his face as well as his feet. He discovered it first on other people, then on himself, and finally came to the conclusion that everybody who goes forth on two wheels acquires the expression to which the new term is applied. This expression may be divided into three parts:

- A wide and wildly expectant expression of the eyes

- Strained lines about the mouth

- A general focusing of all the features toward the center

Disagreement arose shortly after the general description of the indisposition was offered; the article continues:

Scientists took hold of the matter, and advanced theories about it. One learned man said that the bicycle face was the result of constant strain to preserve equilibrium. Up popped another scientist, who stated that the preserving of equilibrium was purely an instinct, involving no strain, and that if the first man knew a bicycle from a bucksaw he’d realize it. Thereupon the first scientist said that the second had a bicycle brain, and hundreds took sides in the discussion.

Turning next to a “prominent bicycle academy instructor…positive that he has solved the secret,” the column, without discounting the role of chewing gum, reveals the causes of the expression’s three parts:

The phenomenon of the wild eyes is acquired while learning the art. It is caused by a painful uncertainty whether to look for the arrival of the floor from the front, behind, or one side, and once fixed upon the countenance, can never be removed.

The strained lines about the mouth are due to anxiety lest the tire should explode. Variations in these lines are traceable to the general use of chewing gum.

The general focus of the features is indicative of extreme attention directed to a spot about two yards ahead of the front wheel. This attention arises from a suspicion that there is probably a stone, bit of glass, upturned tack, barrel hoop, or other dangerous article lying in wait there. It is temporarily lost when the obstacle is struck and the bicyclist’s face makes furrows in the ground, but reappears with increased intensity after every such experience.

By the third week of July the term had become ubiquitous, numbering eleven on, what is best describes as, an ‘advice for women by a man’ column.

Visit the Readex Early American Newspapers page for information on this collection and more.