“Black Representative of a White Idea”: John Willis Menard, 1868 Representative-Elect from Louisiana

A person’s social standing has much to do with where they sit, or whether they’re even allowed to do so. During U.S. civil rights protests in the 1960s, Rosa Parks and other Black citizens went to jail over where they sat on buses and at lunch counters. “Having a seat at the table” is a metaphor for being close to power; to act as the “chair” of a committee is to exercise authority over its proceedings. Courts “sit” in judgment. Examples of such usage are easy to find.

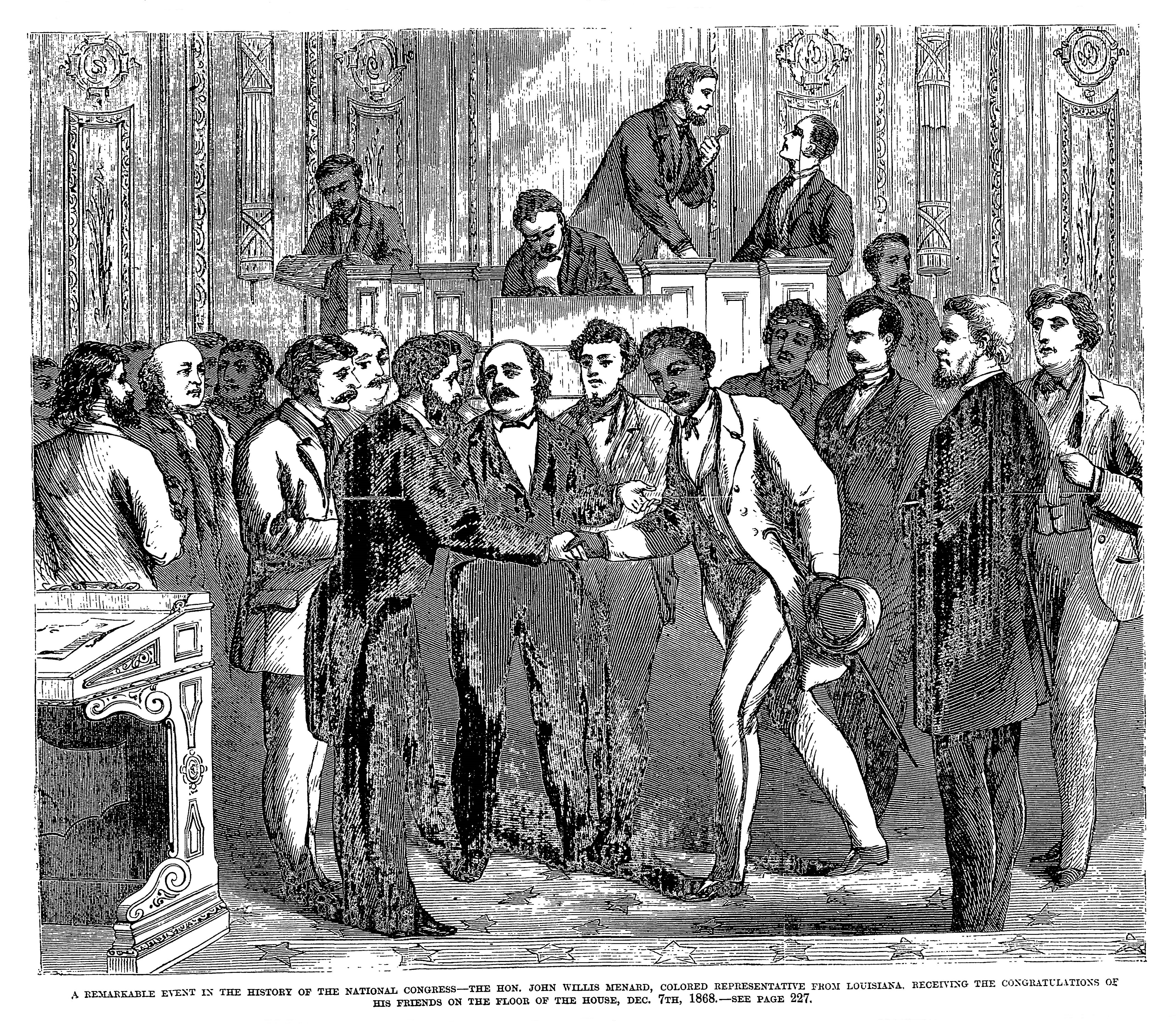

On November 3, 1868, Republican John Willis Menard won a special election to serve in the 40th Congress as U.S. Representative from Louisiana’s second district for the remainder of the term of James Mann, a Democrat who died in office. Menard is known today as the first Black person elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. But his election was contested at several levels and he was not seated, that is, he was not accepted by the House as the official, effective representative of his constituents. Nor was his opponent, Caleb S. Hunt, a White Democrat originally from New England. Nor was yet another contender, Simon Jones, who had contested Mann’s original election of April 1868. The seat was declared vacant, not for a lack of claimants but for procedural reasons that were ascribed in part to racial prejudice.

Menard’s election was irregular in some respects but no more so than many during Reconstruction. Administratively it was relatively routine. Although thousands of votes were thrown out due to violence and intimidation, the results in Menard’s favor were certified by Louisiana Governor Henry C. Warmoth. Menard traveled to Washington, D.C., and was admitted to the House chamber. His bona fides were submitted to the House Committee on Elections. A lively debate ensued over his political status. He was eventually recognized by the Chair. For fifteen minutes on February 27, 1869, Menard addressed the House members in session. He won praise for his eloquence, his informed commentary and his moderate tone. He was eventually paid a salary of $2,500 for his candidacy and intended service. But he was not allowed to serve.

John Willis Menard was born a free Creole in Kaskaskia, Illinois, on April 3, 1838. His parents had roots in New Orleans, and Menard would live and work in that city from 1865 to 1870. In his youth he did farm work, studied at an abolitionist school in Sparta, Illinois, and later attended Iberia College in Ohio, although he did not earn a degree. However, his modest education did not prevent him from establishing himself as a poet. He recited the following poem, “One Year Ago Today” in 1863 during the jubilee celebration of the emancipation of slaves in the District of Columbia:

ONE YEAR AGO TO-DAY

Dedicated to the Emancipated Slaves of the District of ColumbiaAlmighty God! We praise thy name,

For having heard us pray,

For having freed us from our chains

One year ago today.We thank thee, for thy arm has stayed

Foul despotism’s sway,

And made Columbia’s District free,

One year ago today.Give us the power to withstand

Oppression’s baneful fray;

That right may triumph as it did,

One year ago today.Give liberty to millions yet

‘Neath despotism’s sway,

That they may praise thee as we did,

One year ago today.O! Guide us safely through this storm;

Bless Lincoln’s gentle sway,

And then we’ll ever praise thee, as

One year ago today.

Menard spent several years in Canada after college. There’s speculation that his ancestry included French voyageurs, the early fur trappers and explorers. He also served briefly in the U.S. Army as a hospital steward before gaining an appointment as a clerk in the Emigration Office of the Department of the Interior. While there he traveled to British Honduras (present-day Belize) to investigate emigration opportunities for Blacks.

As soon as the necessary arrangements are made, the Company will carry emigrants from different ports in the United States to Honduras, and make suitable provisions for comfortable homes and settlements on their arrival. John W. Menard, a practical farmer from the State of Illinois, is gone to examine its soil, products and its adaptedness for the emigration of farmers and laborers of the African race now in the United States. He will report early in the Fall, and then if favorable, solicit farmers and laborers of the West to form themselves into colonies and remove to Honduras.

FRANCIS HODGE

Agent of the British Honduras Comp’y

St. Thomas, C.W.,

New York, June 15th, 1863.

Menard was also sent to Liberia to make a similar assessment for the Emigration Office.

He visited other potential colonization sites as well, notably Jamaica where he met his future wife, Elizabeth, and welcomed a son into the world. While Menard was in Jamaica, Colonial Governor Edward John Eyre violently suppressed an insurrection known as the Jamaica Massacre or the Morant Bay Rebellion. Philosopher and British Member of Parliament John Stuart Mill was appointed to an investigatory commission and described the situation in the following terms:

The Jamaica Atrocities.

SPEECH OF JOHN STUART MILL.In the House of Commons, July 31, John Stuart Mill spoke on the subject of the atrocities in Jamaica, as follows:

According to the catalogue furnished by the Commissioners, four hundred and thirty-nine of her Majesty’s subjects, men and women, had been put to death, not in action, not in armed resistance to the government, but after they had fallen into the hands of the authorities, and many after having voluntarily surrendered themselves. Some of these were executed without any semblance of trial; others after what were called trials, by what were called courts martial. In addition to those put to death, as many as six hundred at least—men and women—were flogged, some without, some after, so-called trial. Then one thousand houses and other property were destroyed. If the government and the country, after due investigation, thought that all this was justly and properly done, of course there would be no cause for calling on the government to take any judicial proceedings. The case was far otherwise; and that there was serious culpability no one denied.

Menard was arrested on October 27, 1865, for his controversial political views and deported shortly thereafter by the British colonial government. The following is a letter from colonial Secretary of State Lord Edward Stanley to Charles Francis Adams, U.S. Minister to the Court of St. James—the U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain.

SIR: I had the honor to acquaint you, in my note of the 31st of December last, that your communication of the 27th of that month, respecting the treatment of John Willis Menard, in Jamaica, had been referred to the colonial office, and I have now received from that department a copy of a report from the governor of the island, forwarding an extract of a letter on the subject from the clerk of the peace of the parish of St. Andrew, dated November 2, 1865, together with a minute by the late executive committee.

From these documents, which contain all the information that the governor has been able to obtain respecting the case, it appears that on an examination of Menard’s papers, there were found speeches and letters, with his signature printed in America, in which he spoke of his “deep hatred for the ruling class” of that country, and in which the following sentence appeared:

“I am for black nationalities. The prosperity and happiness of our race and their posterity lay in a separation from the white race. The overseer of Albion estate has inaugurated a most hellish system of oppression and imposition in this parish.”

In consequence of the danger which was apprehended from the promulgation of these ideas, the clerk of the peace recommended that Menard, being a foreigner, should be deported from the colony, and this recommendation was adopted by the executive committee, who directed that it should be carried out immediately.

Menard then established himself in New Orleans, first as a customs inspector and then as a commissioner of streets. While there he published a newspaper, the Free South, later known as The Radical Standard. An example of the former title featuring a speech by Menard appears below.

MR. PRESIDENT AND FELLOW CITIZENS OF THE 8TH WARD:—The questions now before the country are in no wise complicated or hard to be understood. They are neither scientific, historical nor mathematical problems, but they are simply questions of common sense, which can be solved by every laboring man on the levee; they are these—Shall loyalty or Disloyalty rule? Second; shall the negro be a full American citizen, or shall he be remanded to the tender mercies of his former condition? These are the two main questions now before the American people. These are questions which will be decided in the approaching campaign. The salvation of the colored race in this country depends directly upon the success of Reconstruction and the Republican party in the South. If these fail, our newly acquired rights and privileges will pass from our hands quicker than they came.

Menard’s newspapers were well regarded and proved widely popular within their politically partisan readership. Menard identified as a Republican, and was regarded as radical in that time and setting, although not to the extent of many who promoted Reconstruction. For all his exertions to gain political office and civil service positions, he was not firmly committed to the assimilation of Blacks in America. Like Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, and others, Menard believed that racial separation and emigration held the greatest potential for Black empowerment and harmony.

Emigration did not necessarily entail leaving the United States. Skipping ahead a bit, in 1889 Menard counseled President-Elect Benjamin Harrison to subsidize Black homesteading in the lands west of the Mississippi River. If Blacks would not go to Africa or to Caribbean and Central American countries, perhaps they could create a homeland closer to home.

An interesting contribution to the solution of the race difficulties in the South is furnished in an open letter “To Gen, Benjamin Harrison, “President-Elect,” by the Hon. J. Willis Menard of Florida, editor of the late Southern Leader.

Mr. Menard has reached the conclusion, by what special pathway of mental perturbation we stop not to discover, that if the Federal government could be induced to furnish free transportation and homesteads in the Western States to at least 1,000,000 colored people, the race question in the South would be reduced to its simplest elements. He estimates that $15,000,000 “would be a cheap solution of the vexed problem.”

Back in New Orleans, in 1866 Menard published the pamphlet, “Black and White,” wherein he advocated that Black citizens focus on self-reliance and self-improvement. Throughout his life he vacillated between trust in America’s democratic institutions and the rejection of those civil structures and processes that had so often frustrated his hopes and ambitions.

So many questions are pressing upon us every day that we have been somewhat delayed in our promised review of that interesting pamphlet. The author, J.W. Menard, is well known to our community; the earnestness, the purity, the elevation of his sentiments will be still better appreciated after a careful perusal of “Black and White.”

Mr. Menard’s main idea, as expressed in the last paragraph of his pamphlet, is that the African race must help itself, and shape its destinies among the races of mankind. The writer shows that the assistance that the black man receives from his friends or alleged friends is insufficient and incomplete, and that the transformation of a whole mass of human beings from a condition of servility and ignorance to one of freedom and enlightenment, requires, ex necessitate rei, a certain period of time. It is but too true, as our author states it, that most of the Republicans, Radicals or Abolitionists, who are the well-wishers of the black man, only sympathize with him in his servile condition.

In 2021 it’s not hard to find accounts of racial violence and political partisanship. Allowing that present-day intolerance is a serious threat to American civic life, readers can be thankful they did not live in New Orleans during Reconstruction when riots were routine, authority ineffectual in guaranteeing public safety, and homicide was embraced as the solution to racial division rather than part of the problem.

Menard’s candidacy for Congress began quietly enough, as noted in September 1868 in the New Orleans Times.

J. Willis Menard, a colored man, who came here a few years ago from Canada, has issued an address to the Radicals of the Second Congressional District, announcing himself a candidate for Congress. He thinks that the white Radicals must be held to their promises—that it is a mockery in the same breath to talk of universal equality and “negro ineligibility.” He wants not only to diminish taxation, but to pay the bondholders in gold!

Bear in mind that the election was scheduled for November 3rd; Menard announced barely one month from that date. He was not sanguine that he would be treated fairly by fellow Republicans. Whether he was running in earnest, trying to raise his profile or just wanted to highlight certain issues through a quixotic campaign, the dire circumstances of Reconstruction would have forced him to consider seriously the personal implications of throwing his hat into the congressional ring.

Here’s a brief account of conditions in New Orleans in the days leading up to that 1868 election. These atrocities are by no means unusual for that period in history. Homes were burned down and families destroyed. The streets became shooting galleries. Political participation in the South at the time was akin to blood sport.

About 2 o’clock to-day, a riot broke out near Trémé Market, in which two white men and three negroes were killed.

At the French Market, three negroes were wounded and one killed.

The cavalry is being dispersed through the city.

A few minutes after 1 o’clock a negro man named Jacob Harcourt fired on two men walking near the Trémé Market. The aim of the negro was bad, and he failed in killing the man. He was immediately fired upon and killed.

Everywhere throughout the city the utmost excitement prevails. Men are arming in the Fourth and Second Districts, and whenever a man appears on the street with a gun or armed he is fired upon by negroes.

The utmost excitement prevails throughout the city.

The police is nowhere to be seen, and there is no protection to life or property.

Given the environment in which he ran for office, the miracle of John Willis Menard is not that he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, even with an asterisk next to his name, but that he wasn’t assassinated for his presumption to claim for Blacks a seat in a bastion of White privilege.

The battle for election in Menard’s district was daunting. The seat was already contested by Colonel Simon Jones, a Radical Republican who had run against James Mann in April 1868. Worse, Louisiana redistricted New Orleans after Mann’s election but before the November 3rd election; Menard wasn’t even running in the same district as before. Both Menard and another rival for Mann’s seat, Lionel A. Sheldon, had their own opponent in Caleb S. Hunt, an inventor and associate of a Northern firm that sold cotton gins and machine parts in Louisiana. The ad below from 1870 provides a fair example of Hunt’s business interests.

Even in his native New England Hunt was described as a carpetbagger, a Northerner who moved to the South to profit from the turmoil and misery of Reconstruction. He was born in New Hampshire and worked in Massachusetts before moving to Louisiana. As a purveyor of cotton gins his interests would naturally have aligned with those of the White planters.

CARPET-BAGGER.—Caleb S. Hunt, formerly of Bridgewater, is a Democratic candidate for Congress in Louisiana. At the beginning of the war he was agent at New Orleans for the E. Carver Company, of Bridgewater, manufacturers of cotton-gins, and joined the rebels.

Finally, during the upheaval of Reconstruction many political opportunists mounted specious campaigns in elections whose results they planned to contest as money-making schemes. Unsuccessful contestants were compensated financially by Congress on the presumption that they had run in good faith and would serve if their claims had merit. Unfortunately many of the aspirants lacked merit to begin with. Hunt would receive $2,500 for losing to Menard. His claim for $2,000 for losing his bid for Mann’s seat in the 41st Congress was listed in an 1870 article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer criticizing the “business” of running for office. The excerpt below frames the scheme as a Radical Republican enterprise but of course it worked equally well from the other side of the political divide.

Contesting seats in the House of Representatives has become a business, and a good paying business it is, too. If a radical candidate in a Southern district is less than ten or fifteen thousand in a minority, he contests his opponent’s seat, and Congress declares the seat vacant and pays a bonus to both parties. This business, it is needless to say, is carried on at the public expense.

In Menard’s election, due to violence and fraud the tabulation was messy to say the least.

The canvass of the votes cast in this State at the election on the 3d inst. was concluded yesterday by Gov. Warmoth, the Secretary of State and the Judge of the Second Judicial District Court. As intimated in the Picayune in its morning and evening editions of yesterday, the “trio” above mentioned decided to throw out the votes of the parishes of Orleans, Jefferson, Avoyelles, West Feliciana, Franklin, Jackson, St. Bernard, Sabine, St. John the Baptist, St. Martin, Terrebonne, and Washington, for alleged irregularities. The total vote of the State, as reported to the Secretary of State, for President was as follows: for Seymour, 74,672; for Grant, 34,224. Throwing out the parishes above mentioned reduces the vote for Seymour to 41,358, and that for Grant to 27,911, and the Democratic majority to 13,447.

The results of the exclusion of the parishes noted above were tallied in the U.S. Congressional Serial Set: Menard ended up with the certificate of election as the most credible, least compromised candidate.

If readers find the above tangle of candidates and claims confusing, they can take solace in the fact that the members of the U.S. House of Representatives also struggled to make sense of things. Debates as to the legitimacy of elections, ballot counts, fraudulent returns, certifications and candidates went on for months. Race was noted as an implicit factor in the decision not to seat anyone from these elections but it was not the only factor. A number of Republicans expressed regret that they could not categorically endorse Menard as the first Black congressman. House Democrats had a field day lampooning the sincerity of their Republican colleagues.

When he (and Ulysses S. Grant) won their respective elections, Menard’s exhilaration spilled out in the form of the poem, “Our Chief.”

Once more, O harp! Let me gently touch

Thy thrilling numbers soft and sweet—

Once more with new-born energies

The King of Liberty to greet!

With joy complete,

And hope replete,

Thy notes of triumph now repeat!All hail the Chief! The good, the great—

The new-made King of Liberty!

Let cannon, bell, and trumpet sound,

From mountain, valley, plain, and sea!

And Dark and Light

No longer fight

For Wrong has yielded unto Right!From icy North to sunny South,

Let the proud flag of Freedom wave!

Let its broad, starry folds, unfurled,

The storms of dark Oppression brave!

For Heaven gave

No man a slave

The sweets of Liberty to crave!This land is Freedom’s heritage—

The home of Liberty and Peace;

And Treason, with its fiendish deeds,

In the fair, sunny South, shall cease:

And God, to Thee

We bend the knee,

And thank Thee for our victory!

On December 16, 1868, the New York Herald published a fascinating interview with Menard after he had won but before he had been dragged through the vetting process. The unnamed journalist found Menard in a surprisingly modest rooming house in Washington and began the article in a flippant, dismissive tone. But he asked him serious questions, and received thoughtful answers in reply. It’s clear that by the end of the interview the writer had been won over by Menard’s sincerity and political acumen. When Menard was shunned by the House members generally, two other journalists who also took him seriously began to introduce him to House members whether the latter desired to make his acquaintance or not. Some coverage of Menard was gratuitously racist, but overall the “fourth estate” did very well by him, perhaps because he was one of their own.

REPORTER—How did the republicans on the floor of the House receive you the day you made your appearance?

MENARD—Well, nothing extra. I had to find my way in, and when inside I found nobody inclined to come near me. I felt bad at this. I didn’t want to sit there and be stared at like a curious kind of an animal, and if nobody cared to talk to me I wasn’t going to force my company on them. I walked in on that floor feeling that I had a right to do so, and a good deal better right than these carpet-baggers, Newsham and Sypher, from Louisiana, elected by colored votes in the places of better men.

REPORTER—Did these men see you on the floor?

MENARD—Yes, they saw me, but that was all. They never once came to ask me how I was or introduce me to some of the prominent members. I felt greatly incensed and indignant at this, because I know how ready they were to shake hands with me and poorer colored men when they were down in Louisiana looking for office.

REPORTER—Who among the members showed you any kindness?

MENARD—None of them, to speak of. The only kindness I experienced was from two newspaper reporters; but I suppose they had a meaning for it. One of them belonged to an illustrated paper and wanted to make a sketch of me; the other wanted to get a short history of my life; and between them I was an object of affectionate attention. They were the only persons I met that brought me round and introduced me to members of Congress.

REPORTER—How did the members receive you?

MENARD—Well, I could easily see that they didn’t like it much; the carpet-baggers from Louisiana edged away the moment they saw me in their neighborhood. Altogether I felt disappointed and uncomfortable, and resolved never to go in upon that floor again until I went to take possession of my seat.

As disinclined as the House members were to talk with Menard, they were all too happy to talk about him, in session and at length. The Daily Globe—the official newspaper of Congress [masthead motto: “The world is governed too much.”]—is replete with “radical” congressmen pleading to have Menard seated while others poked fun at the whole enterprise, and still more hid behind technicalities to prevent a Black person from having an official voice in government. It’s a remarkable performance, a political melodrama couched in parliamentary language nearly 100 years prior to the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

The following exchange regarding compensation for the failed candidates appeared in the Daily Globe after they had all been refused Mann’s seat. Henry L. Dawes, Republican from Massachusetts; Hamilton Ward, Republican from New York; John M. Broomall, Republican from Pennsylvania; and Michael Crawford Kerr, Democrat from Indiana are quoted.

MR. DAWES. I do not yield to anybody. I appeal to the House that they will not be carried away by their prejudices against color and race. [Laughter.] I appeal to them to do justice to the first black man who ever came here with a certificate that he was elected to a seat in this House. I appeal to them not to treat him by one rule and the white man by another. I ask the gentlemen who passed the constitutional amendment to see that this is not done. Mr. Speaker, it is unconstitutional to treat him differently. [Laughter.]

Mr. WARD. I ask the gentleman to yield to me.

Mr. DAWES. I desire to acquit the Committee on Accounts of acting from any prejudice against color. It is a mistaken view of their duty, Mr. Speaker, that has induced them to commit this extraordinary error, and I desire to acquit my most esteemed friend from Pennsylvania.

Mr. BROOMALL. The gentleman from Massachusetts knows as well as any member of this house that I make no distinction [between] race and color upon which his whole charge has been based. The committee rejected the claims of the two men, one a little whiter and the other a little darker than the gentleman from Massachusetts. [Laughter.] One was a Democrat and the other a Republican, and I regret that I am not enabled to say which was the Democrat and which the Republican, but I presume that the one nearest the color of the gentleman from Massachusetts was the Democrat. [Laughter.] I wish to put this matter on its right footing. The gentleman ought to have known when he was making the charge that it was unfair.

Mr. KERR. I want the House to understand that both these gentlemen are Republicans. [Laughter.]

This retrospective passage from the 1883 New York Globe excerpts Menard’s February 27, 1869, speech and gives examples of the press coverage of that momentous event. Caleb Hunt, his opponent, did not speak.

Although he held the Governor’s certificate of election, a Republican House refused to seat him on account of certain technicalities. He received full pay, however, and was all0wed to speak on his case. These were his open words: “Mr. Speaker, I appear here more to acknowledge this high privilege than to make an argument before this House. However, as I have been sent here by the votes of nearly 9,000 electors, I would feel myself recreant to the duty imposed upon me if I did not defend their rights on this floor. I do not expect, nor do I ask, that any favor be shown me on account of my race, or the former conditions of that race.” The leading papers of the country spoke very favorably of Mr. Menard’s speech and appearance in Congress. The Cincinnati Commercial said: “If Mr. Menard’s appearance was striking, no less evident was the surprise at the matter and manner of his address. Calm, self-possessed, he gave, in good sense and choice phrases, his reasons for a claim to a seat in Congress.” The New York Herald said: “Mr. Menard delivered what he had to say with a cool readiness and clearness that surprised everybody. He spoke very distinctly, and commanded more attention than nine-tenths of the members generally. There was a good number of colored people in the galleries, who evidently viewed their champion on the floor with pride and affection.” The Daily Washington Chronicle said: Mr. Menard acquitted himself so well as to elicit the congratulations of some of the most prominent Republicans in Congress." The Worcester (Mass) Spy said: “Mr. Menard’s manner is pleasant and gentlemanly, while his voice is refined and modulated. He is a gentleman of education and fair abilities.” The Philadelphia Press said: Mr. Menard’s demeanor, language and sentiment were fortunately such as to gain for him the sympathy of every man who heard him.” The Chicago Tribune said: “It was not Menard alone that stood on the floors of the National Capitol last Saturday. The millions of his race, just freed from fetters, stood firmly there. He stood, the black representative of a white idea, beside the white representative of a black idea—his equal before the law, his superior before God.”

After Menard was denied a seat in Congress, his life appeared to run off the rails for a few years. Two significant developments likely precipitated his removal from New Orleans to Jacksonville, Florida, in late 1870 or early 1871. The first was a charge against both Menard and his wife of the attempted rape of Amelia Hays, a domestic worker living with his family.

J. Willis Menard, colored, who contested the seat of Bailey, from the Second Louisiana district, in Congress, was yesterday sent before the Criminal Court, charged with attempting to outrage the person of Amelia Hays, a quadroon girl living with his family. Menard’s wife was accused as an accessory. He was held in $500 bail to answer the charge.

There is also an item from April 1870 listing Menard as a possible victim of forgery and fraud in the amount of $1,664 by Louisiana State Auditor George M. Wickliffe. A combination of financial stress and social opprobrium stemming from the rape charge may have induced Menard to seek a new beginning in Florida.

At the office of the State Auditor we yesterday obtained the following list of warrants fraudulently issued by Wickliffe, showing the date, the amount and the name of the party in whose favor they purport to be drawn. The warrants in possession of the Auditor are not all, however, that were embraced in the transaction with Mr. Strauss. Eleven others, amounting to $50,465, have been surrendered to the police by Mr. S. Friedlander, who seems to have been a joint purchaser with Mr. Strauss from Wickliffe, and these are still in the hands of the police:

Yet another disaster that befell Menard and his family at that time was the seizure and tax sale of his New Orleans real estate in 1871. He appears to have purchased the property following assurances from Congress that he would be paid $2,500 for his 1868 candidacy. It’s not clear when he was actually paid; the House members were still debating whether and how much to pay others in his situation in January of 1873. The property may have been abandoned when Menard and his family left New Orleans.

William M. Geddes vs. J. Willis Menard.

SEVENTH DISTRICT COURT FOR THE PARISH of Orleans, No. 3940.—By virtue of a writ of seizure and sale to me directed by the honorable the Seventh District Court for the parish of Orleans, in the above entitled case, I will proceed to sell at public auction, at the Merchants and Auctioneers’ Exchange, Royal street, between Canal and Customhouse streets, in the Second District of this city, on TUESDAY, August 15, 1871, at twelve o’clock M., the following described property, to wit—

TWO LOTS OF GROUND in the late parish of Jefferson, now the Sixth District of this city, in the square bounded by Constantinople, Marengo, Apollo and Nayades streets, and designated by the numbers twenty-one and twenty-two; said lots adjoin each other, and measure thirty feet front on Constantinople street, by a depth of one hundred and twenty feet, with the buildings and improvements thereon.

Being the same lots acquired by the present defendant from Christopher Koldenberger, as per act passed before E.G. Gottschalk, a notary public in this city, on the twenty-third day of March, 1869.

Seized in the above suit.

In Florida Menard initially kept a lower profile. He lived first in Jacksonville, then in Key West. He published several newspapers, served in the Florida state legislature, ran unsuccessfully for Congress again, and held a succession of civil service positions in the Post Office, the Customs Service, and the Census Bureau. In 1880 he published a book of poetry, Lays in Summer Lands.

For a time he was even a school principal. His great-granddaughter, Edith Menard, also worked in education as an English teacher at Woodrow Wilson High School in Washington, D.C. She reminisced about her great-grandfather’s legacy during an interview in 1991 on the occasion of William Jefferson’s election to Congress as the first Black representative from Louisiana since Charles Nash was elected in 1874. Seventy-one year-old Edith playfully suggested that to honor her ancestry she might run in the 1992 election as the District of Columbia’s representative.

Menard’s move to Florida did not quell his criticism of racial politics even when expressed by luminaries such as Frederick Douglass. Menard had an appreciation of Realpolitik or “practical politics.” He was interested in what was possible rather than in the achievement of an ideal of racial and political harmony. The following appears in his 1883 critique of Douglass’ call for a Colored National Convention.

(3) Our civil rights are still infringed upon all over the country, notwithstanding the passage of the acts of Congress for our protection in that particular.

If Congress and the President and the Federal Courts, backed up by the Army and Navy, have been powerless to enforce our civil rights, what supernatural power could be invoked by a Colored National Convention to eradicate the prejudices of the whites? Could it be done by brilliant resolves and windy speeches? Not at all. As the 4th, 5th, and 6th objects of the call are equally untenable, and the evils complained of beyond the surgical, or rather fancied magical, powers of any convention, there seems, really, no necessities at this time for the proposed convention.

I have great admiration and profound respect for Mr. Douglass, and believe that he and the other gentlemen whose names are attached to the call, have made an error of the head and not of the heart, in calling the proposed convention. The remedy for the evils complained of can only be found in the political divisions of the Southern whites, and in local alliances between the colored people and the liberal white element, as exemplified in Virginia. The causes which have solidified the whites since the war have been removed, and as “carpet-bag rule” has been swept away, they will naturally again resolve into separate political elements by local causes and jealousies. In rivalry and strife of the factions thus generated, the Negro will find fair chances for effective and profitable alliances, through which he will secure redress for his grievances. My experience of fifteen years in the South leads me to believe that this is the only way which tends to our political salvation.

Inveterate journalist that he was, shortly before he died in 1893 Menard founded a monthly magazine, the National Afro-American, in Washington, D.C., where he moved in 1889 to accept a clerkship in the Census Office. He lived to see the first Black person actually seated in the U.S. House of Representatives, Joseph Rainey, a Republican from South Carolina elected in 1870; and the first Black U.S. Senator, Hiram Rhodes Revels from Mississippi, also elected in 1870. It’s fitting that Menard came home to Washington at the end of his life, where he’s buried in historic Woodlawn Cemetery with his wife, Elizabeth, just a few miles from the Lincoln Memorial.