“The Caucasian will not tolerate the Mongolian”: The Racism of Chinese Exclusion in the United States, 1848-1911

The history of Chinese immigration to the United States, from the Gold Rush to World War II, is uniquely the one instance in which American law has specifically barred an entire national or ethnic people from entering the country under most circumstances and from any possibility of citizenship. Although such draconian measures did not become federal law until 1882 when the Chinese Exclusion Act was signed by President Chester A. Arthur, the seeds were spread for over 30 years, particularly in California.

California became part of the United States in 1848 as a result of the Mexican-American War. The occupation of coastal areas by settlers from the American East opened the country to Pacific trade and transportation. Between 1848 and 1855 as many as 300,000 people, mostly men, swarmed to California, including those from China. In the 1850 census there were 4,018 Chinese in the U.S.; ten years later the census showed a ninefold increase to 34,933.

In 1855 the Augusta Chronicle reported:

The Chinese population of California continues to engross much of the attention of the authorities of that State. In the lower house of the Legislature, the subject having been referred to a committee, two reports have been the result. The majority report advocates the expulsion of the Chinamen from the mines, while the minority report takes the opposite view of the case. A Mr. Johnson has also introduced into the Assembly, a bill which provides that immediately on the arrival of persons not eligible to citizenship under the laws of the United States, the captain or consignee of the vessel on which they may have been brought, shall file a bond in the [illegible] sum of $500, conditioned that they shall not commit any crime or misdemeanor during their stay in the State.

In the years between 1855 and 1882 Chinese people in the United States were demeaned and constricted by state courts and laws. A notorious decision of the California Supreme Court in 1854 overturned a murder case brought against a white man for killing a Chinese man. The eyewitnesses were also Chinese. Their testimony was ruled inadmissible based upon a stunningly racist assessment of all Chinese people.

This virulent racism made law is manifest in a resolution of the legislature of California to the U.S. Congress which implored the federal government to modify the Burlingame Treaty with China of 1868. The treaty allowed for emigration under relatively benign conditions. The California legislature argued that “the great influx of Chinese…has proved detrimental to the moral and material well-being of our industrial classes…” because “Mongolian labor has driven from employment large numbers of our people by a competition which has been prolific of idleness, vice, and suffering among our people, thereby assisting to fill our jails, poor-houses, and hospitals with unwilling inmates…” White men were being forced into vice and idleness by “a servile laboring element whose low standards of living and morality menaces the communities in which it may reside with pestiferous disease…”

Casual racism was common. Senator James G. Blaine was seeking the 1880 presidential nomination from the Republican Party. The Exclusion Act was gaining congressional support. In 1879 a Mississippi newspaper published this view from a Midwestern paper:

The Kansas City Times says Jim Blaine dug his political grave in favoring the exclusion of the Chinese. New England Radicalism will never slam the door in the face of Ah Sin while admitting the Teuton and Celt. In attempting to save his presidential goose, Mr. Blaine has cooked it.

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was to sunset in ten years. Consequently, it was extended and harshened with the enactment of the Geary Act of 1892. Its eponymous author, Congressman Thomas J. Geary of California, burdened the Chinese with new legal requirements, including carrying a Certificate of Residence at all times and being sentenced to hard labor or deportation if apprehended without it. As with the 1882 law, so the Geary Act was to expire in ten years. By 1902 the issue of reenactment dominated much of the political discussion and activity.

The Chinese Exclusion Convention, assembled by the Board of Supervisors of the city and county of San Francisco, met on November 21 and 22, 1901. The conventioneers determined on this petition to Congress.

The racism in this document is more than casual.

The effects of Chinese exclusion have been most advantageous to the State. The 75,000 Chinese residents of California in 1880 have been reduced, according to the last census, to 45,600….Every material interest of the State has advanced, and prosperity has been our portion. Were the restriction laws relaxed we are convinced that our working population would be displaced, and the noble structure of our State, the creation of American ideas and industry, would be imperiled if not destroyed. The lapse of time has only confirmed your memorialists in their conviction, from their knowledge derived from actually coming in contact with the Chinese, that they are a nonassimilative race, and by every standard of American thought undesirable as citizens….they have not in any sense altered their racial characteristics, and have not, socially or otherwise, assimilated with our people.

The debasement of the Chinese continues in full force including the assertion that the offspring of any intermarriage with them

has been invariably degenerate. It is well established that the issue of the Caucasian and the Mongolian do not possess the virtues of either, but develop the vices of both. So physical assimilation is out of the question.

Continuing:

The purpose, no doubt, for enacting the exclusion laws for periods of ten years is due to the intention of Congress of observing the progress of those people under American institutions, and now it has been clearly demonstrated that they can not, for the deep and ineradicable reasons of race and mental organizations, assimilate with our own people and be molded as are other races into strong and composite American stock.

And, finally:

The Chinese, if permitted to freely enter this country, would create race antagonisms which might provoke domestic disturbance. The Caucasian will not tolerate the Mongolian. As ultimately all government is based on physical force, the white population of this country will not, without resistance, suffer themselves to be destroyed.

In early 1901 the American Federation of Labor (AFL) published a pamphlet, reprinted in the Congressional Serial Set, titled “Some Reasons for Chinese Exclusion. Meat vs. Rice. American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism. Which Shall Survive?” On January 15 of that year the U.S. Senate issued a response, beginning this way:

Inasmuch as the laws excluding Chinese emigration are not only to be reenacted but made more drastic in their enforcement, it behooves thinking men and patriotic Americans to calmly review the history of this legislation, and the present condition, which, instead of calling for severer laws, should under all circumstances demand less restrictive legislation and more humane interpretation by the executive branches of our Government.

The author marshals a series of responses to the AFL’s assertions, citing specific pages and refuting its arguments for continuing to exclude Chinese persons from the United States. The pamphlet’s allegations included unhygienic living conditions, morals, opium dens, trade, remittances, and more. An example of the itemized refutations:

“Chinese are not assimilative.” Americans do not give them a chance. They are not allowed by law to become citizens. It is hardly fair to deny them the right to become naturalized and, in the same breath, find fault with them for not being assimilative.

As 1902 progressed the drumbeat in favor of maintaining and tightening Chinese exclusion grew louder. Some proponents were more overt than others in exerting the primacy of white workers’ right of primacy over that of Asian people in particular. Witness the “petition from 319 citizens of Honolulu, H.I., praying for the complete exclusion of both Japanese and Chinese, or their descendants, from American territory,” dated April 8, 1902. At the time, according to the 1900 census, the ethnic makeup of the Hawaiian Islands included 28,819 Caucasians, 25,767 Chinese, 61,111 Japanese, and 37,656 Native Hawaiians.

During this period most of Hawaii’s white population were newcomers from the mainland who had supported the overthrow of the monarchy and the annexation by the United States in 1893. The petition to Congress from these Honolulu residents cited:

First. That the present and future prosperity of this nation depends in great measure on the maintenance of the present high standard of living of its inhabitants.

Second. That this standard can not be maintained if the sphere of the American mechanic is invaded by the hordes of Asia, whose mode of life enables them to live comfortably on a sum which to an American would be a mere pittance.

Third. That at present fully 75 per cent of all the labor of the Hawaiian Islands, both skilled an [sic] unskilled, is being performed entirely by orientals [sic].

Perhaps the most fulsome objection to the extension of exclusion of the Chinese was made by Senator George Frisbie Hoar of Massachusetts. His speech was reported by the Worcester Daily Spy on April 11, 1902.

“It is not a race,” said he, “but it is degradation that we ought to strike at and keep out of this country if we can. The objection to the legislation proposed is that you strike at men, not because of their individual degradation but because of race.”

The advocates of the pending measure, he said, maintained that every Chinaman should be kept out of the United States, even if he possessed every known virtue and that all other foreigners should be admitted even though they may have every known vice.

“That,” said he, with great feeling, “is a stab at the essential principles on which this republic is founded. I will not mark the close of my life by joining in such an act. We have been going on with this sort of legislation step by step. We could not wash out this spot with water and so we took vinegar. We could not wash it out with vinegar and so we tried a solution of cayenne pepper. And now comes the Pacific coast to us with a proposition of vitrol [sic] which they hope will work. I will not for this bill. I will not bow the knee to this baal. I will not worship this God whom you have set up.”

One argument against exclusion did not meet the lofty reasoning of Senator Hoar. Rather, it might better be consigned to the “you just can’t find good help anymore” file. The argument appeared in the Springfield Republican on April 9, 1902.

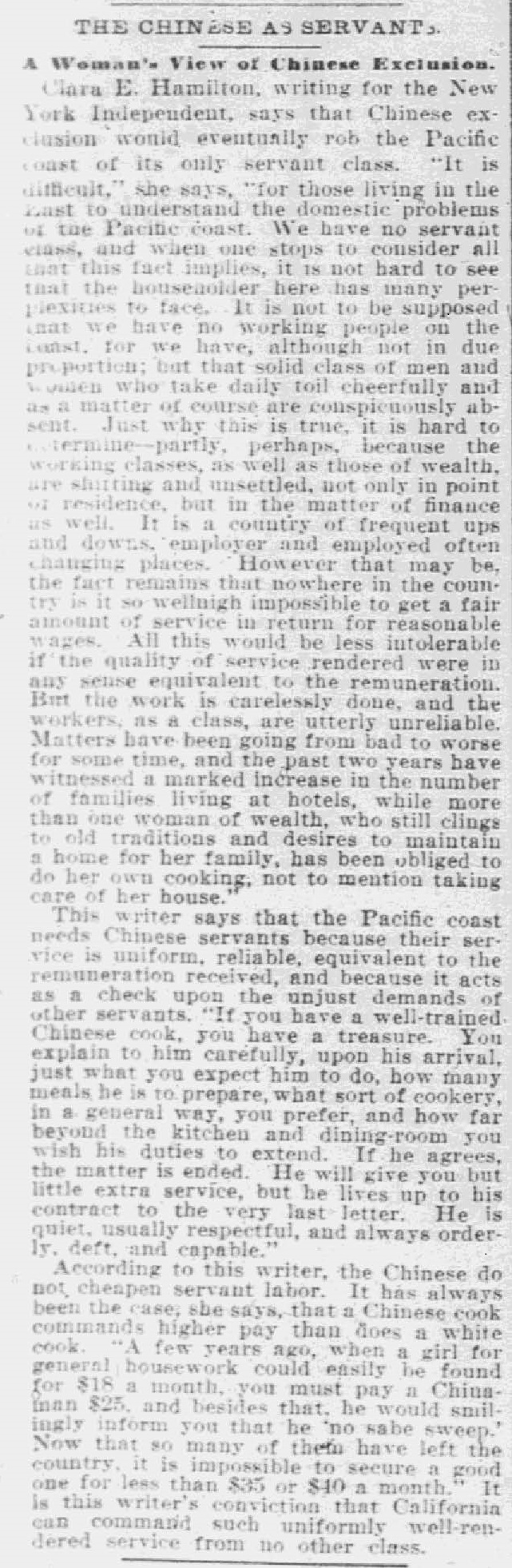

The Chinese as Servants.

A Woman’s View of Chinese Exclusion.

Clara E. Hamilton, writing for the New York Independent, says that Chinese exclusion would eventually rob the Pacific coast of its only servant class. “It is difficult,” she says, “for those living in the East to understand the domestic problems of the Pacific coast. We have no servant class, and when one stops to consider all that this fact implies, it is not hard to see that the householder here has many perplexities to face. It is not to be supposed that we have no working people on the coast, for we have, although not in due proportion; but that solid class of men and women who take daily toil cheerfully and as a matter of course are conspicuously absent…”

Ms. Hamilton bemoans the plight of those in need of servants, the current situation in which servants are slovenly, careless, and unreliable. Things are so dire that there has been

“...a marked increase in the number of families living at hotels, while more than one woman of wealth, who still clings to old traditions and desires to maintain a home for her family, has been obliged to do her own cooking, not to mention taking care of her house.”

She concludes by arguing that

the Chinese do not cheapen servant labor. It has always been the case, she says, that a Chinese cook commands higher pay than does a white cook. “A few years ago, when a girl for general housework could easily be found for $18 a month, you must pay a Chinaman $25, and besides that, he would smilingly inform you that he ‘no sabe sweep.’ Now that so many of them have left the country, it is impossible to secure a good one for less than $35 or $40 a month.” It is this writer’s conviction that California can command such uniformly well-rendered service from no other class.

The racism in this woman’s argument is pervasive but relatively subtle compared to the sort that was increasingly informing the debate and related reportage even after Congress extended the Exclusion Act. Some examples:

Chinks Register Kick. Boycott to Be Used by Chinese Because of Exclusion Act.

Chin Pac “No Likee.” His Third Arrest Under Chinese Exclusion Act Tires Him.

Californians Fight for Exclusion Act. Want Strict Rules Against Chinese And Also Favor Keeping Out The Japs

The word invasion and its conjugations were frequently employed by politicians and reporters alike. Despite the racism, the need for labor stimulated demands for amending the law. A headline in the Bellingham Herald on April 5, 1911, inelegantly announced “Hawaii Wants Contract Chink Labor. Legislature Will Memorialize Congress for Modification of Chinese Exclusion Law—Cheap Labor Wanted to Work Sugar Plantations.” Hawaii had a labor shortage because “labor agents from the Pacific coast…have been recruiting Filipinos and Porto Ricans for work in the fish canneries of Alaska and in the fruit growing districts of California.” The stated purpose in allowing Chinese laborers in would be to “offset the influx of Japanese.”

Recalling that as recently as 1902 Californians had energetically sought the extension of Chinese exclusion, this letter to the editor published in 1910 is of interest. The letter was submitted “on behalf of the Chinese residents” by the Chinese League of Justice of America relative to the California State Labor Commissioner’s report that found “some form of Oriental labor is necessary if the crops are to be gathered.” An editorial from the San Francisco Chronicle is cited:

“The Japs are utterly undependable and the Hindoos are worse; if we were going to have Oriental labor at all, the only proper course would be to repeal the Chinese exclusion act and exclude the Japanese and Hindoos; we should then at least have Oriental labor which would keep its contracts.”

The writer also cites a San Francisco Examiner editorial asserting “the Chinese are the ideal for this sort of labor,” and that “The Commissioner himself notes that Chinese labor is best adapted for this work. On every hand, farmers, miners, railroad construction men and orchardists, all have a good word for the old Chinese labor they one time had and which they badly need now, but which the exclusion act denies to them, for Chinese laborers are now almost as ‘scarce as hen’s teeth,’ and almost as costly from a wage standpoint as ‘precious stones.’”

The bipartisan Dillingham Commission, formally the United States Immigration Committee, was formed in 1907 to investigate the effects of immigration. The Daily Picayune reported in 1911:

Many radical changes in the immigration law are provided under the terms of a general bill which will be introduced in the Senate to-morrow by Senator Dillingham….

The measure proposes to repeal the Chinese exclusion laws except so far as they relate to naturalization. In their place is substituted an amendment to the general immigration law which provides for the exclusion from the United states of “persons who are not eligible to become citizens of the United States by naturalization.”

The bill incorporated many of the recommendations included in the “Reports of the Immigration Commission” which was presented by Dillingham on December 5, 1910.

The amendments also served to make immigration from countries such as Italy, Poland, and Armenia more difficult. Still, the Chinese remain the only national or ethnic people to have been barred by the federal government from both immigration to the United States and from the possibility of citizenship.