“Choose your goal, and success is yours…Follow it, even though you may never reach it.”: Lloyd Gaines and the Case Against the University of Missouri

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education and declared state laws establishing “separate but equal” public schooling to be unconstitutional. This well-known case was a catalyst for the civil rights movement that followed. However, before Brown, there was the Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada case, which was once called “a body blow” to Missouri’s “Jim Crow” laws.

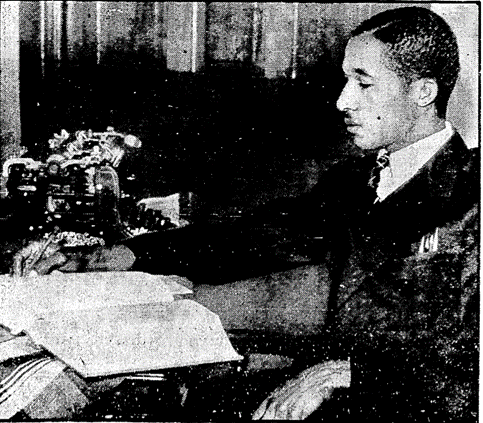

Lloyd Gaines graduated from Lincoln University with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1935 and applied to study law at the University of Missouri law school. At the time, Missouri was one of 17 states that held laws on the books calling for segregation in public education which included higher education. The University of Missouri was the all-white school, while Gaines’ alma mater, Lincoln University, was the state’s public university designated for Black students. In 1935, Lincoln University did not provide graduate programs that included professional education, such as a law school.

Prior to the Gaines case, a 1921 act through the Missouri legislature established Lincoln Institute as a University for Black members of the state to attend. It allowed the school’s board of curators to expand programs to anything offered at the University of Missouri. If no programs were available, it would send students to study in an adjacent state with their tuition paid through a scholarship program. This was not a defensible option to Gaines, who contended that students from other states and from countries as far as away as India had been accepted to the publicly funded University of Missouri. It was Gaines' position that, as a state taxpayer, he had the right to study in the state in which he resided and paid taxes.

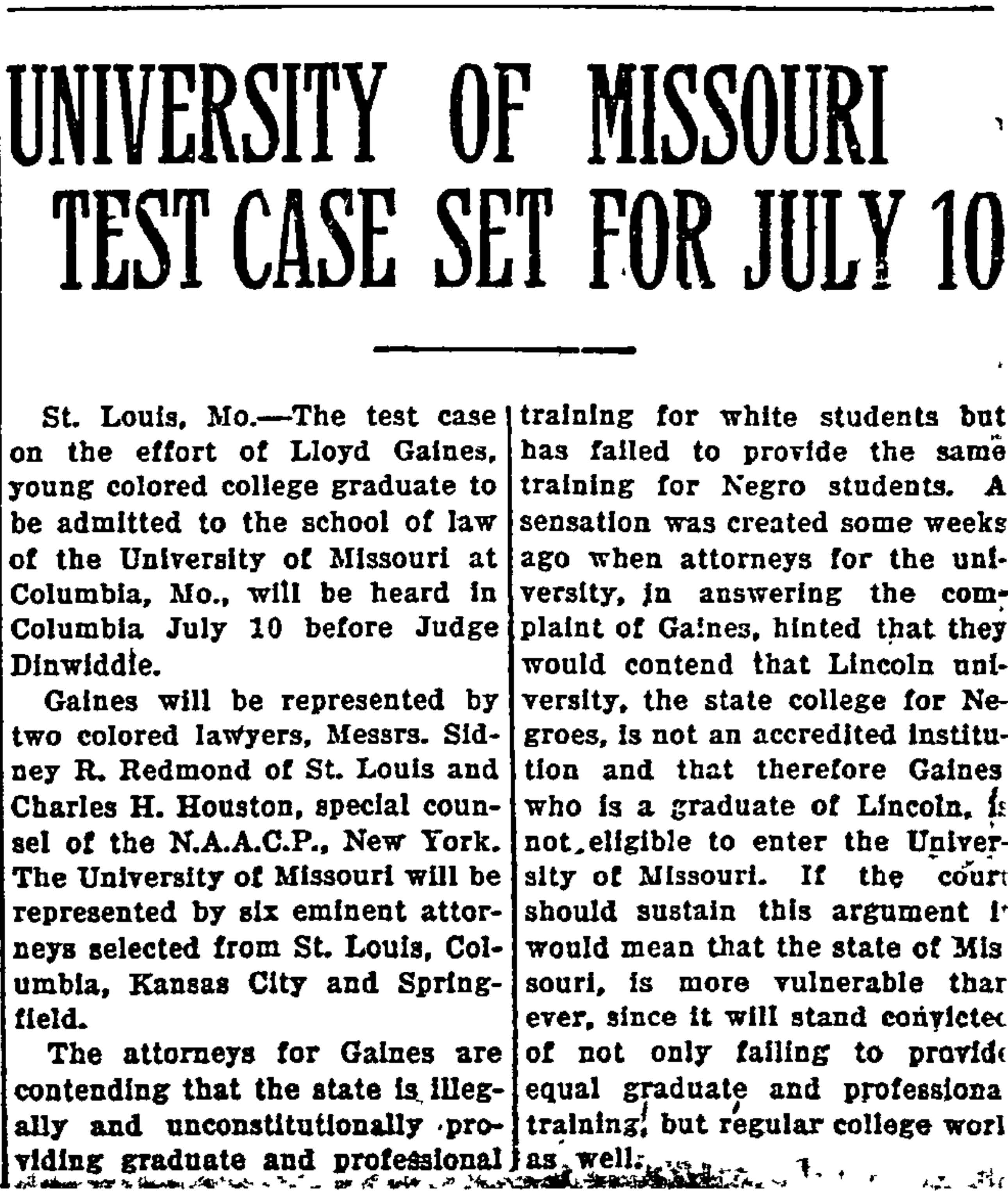

Gaines, represented by Charles H. Houston of the NAACP and Sidney R. Redmond, took the University of Missouri to court over their decision not to admit him due to his race. The case was first brought before the courts on July 10, 1936, in Boone County, Missouri, with Circuit Judge W. M. Dinwiddie presiding. The court brief declared that it was a “denial of United States citizenship rights for the state of Missouri to educate white students at home and exile those of our race to other states.”

In his ruling, Judge Dinwiddie refused to compel the University of Missouri to admit Gaines into its law school. Undeterred and vowing to appeal, if necessary, Gaines’s representatives took the case to the Missouri Supreme Court, where it was heard on May 18, 1937. Again, the courts ruled against Gaines on December 9, 1937.

The Missouri Supreme Court declared that the scholarship to an equal out of state university satisfied the state’s constitutional responsibility of equality. Missouri was not the only state that had such a policy in place. Fourteen other states--Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, Texas, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, Tennessee, Virginia, Arkansas, Louisiana, Maryland, West Virginia, and Kentucky--also had similar programs for sending their African American graduate students out of state.

After the State Supreme Court denied a rehearing on March 8, 1938, the case advanced to the U.S. Supreme Court on October 10, 1938. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled on December 12, 1938, that a state must give “equality” in educational privileges to both white and Black graduate students.

It delivered the opinions of Justice Hughes who stated that compelling Black law students to attend school outside of the state had violated the “equal rights” provision of the Constitution. The two Justices who dissented were McReynolds, a Democrat, and Pierce Butler, a Republican. In Justice Butler’s dissent, he stated the Missouri State Supreme Court “had arrived at a tenable conclusion and its judgment should be affirmed.”

The U.S. Supreme Court ruling required one of two options: Either the state admits Gaines into the law school at the University of Missouri, or it adds a law school to Lincoln University. At the time of the ruling, Gaines was working a WPA-sponsored office job in Michigan but planned to return to his home in Missouri to attend classes at the University of Missouri until the law school at Lincoln was established.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruling reverberated through the other states that relied on sending African American students out of state as a means of satisfying their constitutional obligations. One editor at the Times- Dispatch commented about the decision in Virginia stating the state would have to decide whether to

develop graduate and professional instruction at the State College for colored students at Petersburg at a “cost of a good deal of money” or “admit colored students to instructions of higher learning which heretofore have been exclusively for whites. The second…would be harmful to racial relations in Virginia.

After the ruling, many African Americans began to apply to previously all-white institutions in Kentucky, North Carolina, and Missouri.

The state of Kentucky was "put on the spot" educationally last week with the application of Alfred M. Carroll, 27, for admission to the University of Kentucky's college of law.

Carroll's case parallels that of St. Louis Law Student Lloyd Gaines, who unsuccessfully sought to enter the University of Missouri law school...

In Missouri, Lucile Bluford, a young African American woman, and the managing editor of the Kansas City Call applied to enter the graduate Journalism program at the University of Missouri as Lincoln University did not have such a program and was still denied entry.

The U.S. Supreme Court rejected Missouri’s attempt to have a rehearing and, in an effort to postpone the entry of Black students into the all-white university, the State Supreme Court pushed back a hearing to address the case until May of 1939, allowing Black students to be denied through the end of the school year.

After his U.S. Supreme Court win, Gaines did a series of speaking tours and public appearances with the NAACP. On February 27, 1939, he spoke in the crowded auditorium at Sumner High School in St. Louis, MO. Dr. S. H. Thompson gave an ominous and foretelling remark about Gaines in his introduction, stating that Gaines was a "hero, probably, or a martyr, maybe,” who gave himself in sacrifice for his people."

In his speech to his young audience, Gaines proclaimed some words of advice and inspiration, stating,

Choose your goal, and success is yours. One that is so high that you cannot reach out and grasp it- one that is as clear as the stars above…follow it, even though you may never reach it.

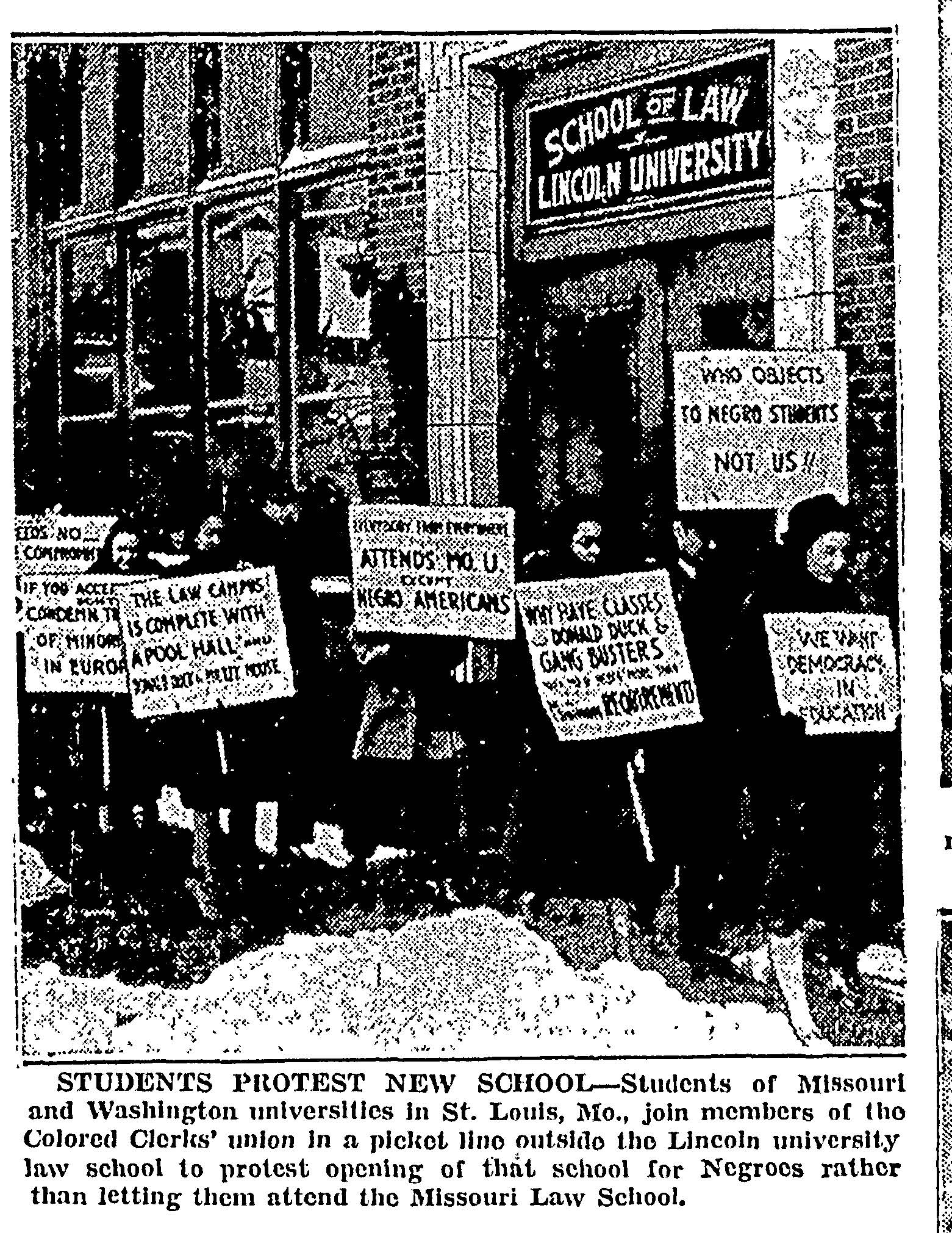

With the U.S. Supreme Court holding firm to its decision, Missouri set about funding an expansion of Lincoln University to include a law school. However, many were not pleased with the end result. Many African American students did not support a separate law school, but instead wanted to attend the University of Missouri. Others who had supported the expansion argued that the school did not meet the U.S. Supreme Court’s requirements for “equal facilities.”

Frank M. Jones, president and organizer of the Colored Clerks Circle, argued, “The Lincoln University Law School is a farce and is inferior in every aspect to that of the University of Missouri school of law and in no wise does it meet with the decision of the supreme court for equal education facilities.”

In late 1939, Gaines’ lawyers began looking for him to testify in a suit against the unequal conditions at Lincoln’s law school, but were unable to locate him. They had last seen him seven months earlier in March of that year. He frequently traveled for public appearances and searched for work, so no one had noticed his disappearance until October 1939. As Gaines was the only person with legal standing in the case, his presence at the hearing was critical.

After months of searching Gaines had not been located. Since Gaines could not be found by January 1940, the state sought a dismissal of the suit, which the court granted. By 1944 the law school at Lincoln University was closed due to lack of funds and enrollment. The fate of Gaines is still unknown though the FBI agreed to look into the case in 2007 as one of a series of cold cases from the civil rights era.

In 2006 Gaines was posthumously granted an honorary law degree from the University of Missouri, and the state bar gave him a posthumous law license. A portrait of Lloyd Gaines hangs in the University of Missouri law school building.

Visit the Readex Black Life in America page for information on this collection