The Early Histories of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Part 1: Howard University

“This institution bids fair to do great good.” — New York Evening Post (1867)

Historically Black Colleges and Universities, commonly referred to as HBCUs, have graduated tens of thousands of men and women who have achieved professional, political, and social prominence. Foremost of these is Howard University, which was chartered by Congress in Washington, D.C., on March 2, 1867.

Howard University was named for Major General Oliver O. Howard, a career military man known as the Christian General. He had served as a brigade commander in the Union Army of the Potomac, sacrificing his right arm in battle. Soon after the South surrendered, Howard was appointed to lead the Freedmen’s Bureau, an agency of the War Department charged with preparing former slaves to take part in society and politics. His allies in Congress were the Radical Republicans who took control after the election of 1866 and instituted a more extensive Reconstruction policy than the previous Congress. Perhaps the most important policy was the passage of the 14th Amendment which federalized equal rights for freedmen and constricted the authority of the defeated Confederate states to inhibit them.

The work of the Freedmen’s Bureau was critical to the advances made in educating Black American citizens and preparing them to be educators, scientists, physicians, lawyers, and judges, including a Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and, in 2020, a Vice President of the United States.

From the outset, the founding of Howard University was met with cheers and brickbats. The Boston Recorder published an article on March 22, 1867, describing the departments and wishing the enterprise well.

This institution located in the District of Columbia, is named after Gen. Howard, and its object is to educate youth in the liberal arts and sciences. It is to have six departments: First, normal; second, collegiate; third, theological; fourth, law; fifth, medicine; sixth, agriculture. While it is to be open to all persons, without regard to race or color, it is designed chiefly for colored men. A fine building has been erected on Seventh street [sic], a short distance beyond the “Boundary,” on a lot of ground containing three acres, adorned by a fine grove of trees. The building is so constructed as to accommodate students with a boarding house. All friends of the colored race will rejoice in its success.

Similarly, on August 8 of that year the New York Evening Post published a positive view of the university.

A charter has been granted by Congress for the “Howard University,” which is to be open to all of both sexes, without distinction of color. This institution bids fair to do great good. The normal and preparatory departments of the university were opened on the 1st of May, and at the close of the month it numbered thirty-one scholars. It has since increased to about sixty. The Bureau alone has provided buildings for fifty-five schools, and assisted in providing buildings for nineteen more. It has furnished houses for forty-five teachers, and given all teachers the privilege of buying provisions of the Commissary officer, and paid their transportation.

Many of the early attacks on Gen. Howard and the university were denominational. Howard was a Congregationalist. A Baptist newspaper made serious accusations as reprinted by the Cincinnati Daily Gazette on August 28, 1867.

From the Washington Star, August 24.

The Intelligencer, in pursuance of its attacks upon Gen. Howard, quotes from a Baptist paper the following:

“Only $10,000 have been given to the National Theological Institute, (Baptist), while $25,000 have been given to Howard University, a Congregational colored school of Washington, by the Commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, out of the large fund of over $100,000, this money being the unclaimed bounty and back pay of deceased colored soldiers from Virginia and North Carolina.

“Now, a very large proportion of the colored people of those states are Baptists, while such a person as a colored Congregationalist can hardly be found from the banks of the Potomac to the Rio Grande…”

The Baptists appear more interested in obtaining their “share” of the money than its purpose.

“…Even if the chief of the Freedmen’s Bureau had technically any right whatever to use any portion of this fund for these purposes, it can hardly be doubted that he has applied it with a sectarian partiality that admits of no excuse. Not only the Baptists, but the Methodists, and the Catholics, and the Episcopalians, had surely as much right to a share of its benefits as the Congregationalists…”

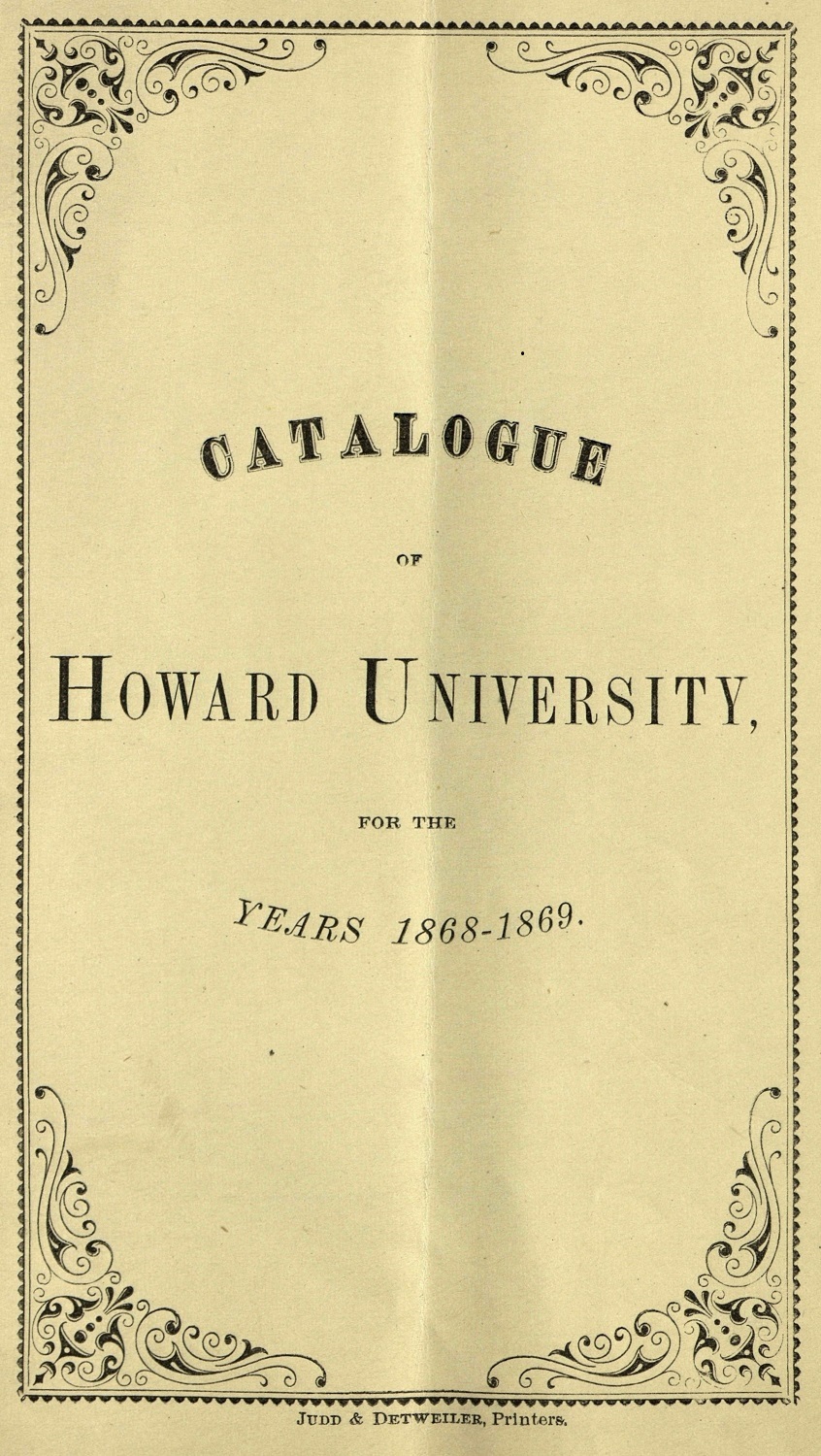

There would be more sectarian accusations and others that reeked of racism. Meanwhile, in 1868 the “Catalogue of Howard University, for the Years 1868-1869” was published. A brief “Preliminary History” was included in which it is stated that the original intent had been for “a theological school.” However, “After earnest and prayerful deliberation and discussion…the original plan was enlarged to embrace all the department of a university.”

The aforementioned New York Evening Post continued to publish reports that supported and encouraged the mission of Howard University. A December 22, 1868, article argued that:

To enable him [the Negro] to guard from encroachment the political equality which has been allowed him, and to make an intelligent use of the privilege of a freeman, the negro must be educated. The great argument against conceding to him the right of suffrage has been his ignorance. He must remove that objection, or he will be in constant danger of either being directly oppressed by laws which have a partial operation, or made the tool of cunning men, who have their own selfish ends to serve at his expense.

The writer also provides information about Howard’s law school which was scheduled to open in early January with an enrollment of fifteen:

It is now desired to obtain funds to endow this department. The object is a worthy one and commends itself to the benevolent. The colored race are [sic] entitled to have agents, advocates and leaders of their own color, and can hardly have a better security for their rights than a class of men among them trained to understand and apply the principles of jurisprudence.

Another opportunity for the naysayers arose when a portion of the Freedmen’s Hospital—now Howard University Hospital—collapsed. The building blocks were alleged to have been faulty. This led to accusations of fraud, self-dealing, and worse. On January 8, 1869, a headline in the Daily Constitutionalist in Augusta, Georgia, included the charge “Bricks a Magnificent Swindle.”

The Washington correspondent of the Cincinnati Gazette gives a racy account of the muddle connected with the Howard University, an institution one of the rear buildings of which tumbled into a heap of ruins the other day.

The allegations of fraud so roundly made in the article were subsequently debunked.

…Howard University has been little less than a means of using over $300,000 of public money for the benefit of a ring of Bureau officers. And this must not be understood as a general statement, but as precise and within bounds. Further than this, it can be made perfectly apparent that the whole scheme centered upon the idea of preparing a rich berth for all the members of the ring when the Bureau should be discontinued.

Fewer than three months later, March 25, the Boston Recorder, among several newspapers, printed a statement from the Secretary of Howard University. It is an account of an evaluation of the infamous bricks, including

reports of four different series of experiments, with from five to sixteen specimens each, to test the amount of pressure the building block will bear, and a chemical analysis of the material. All the architects and practical builders concur in saying that the buildings are well constructed, and the walls stand erect and free from the ordinary defects of an unsound structure.

The report concluded:

Besides this accident, the University buildings have been brought into distrust wholly by hostile newspaper correspondents; but these fine buildings obstinately refuse to show signs of weakness, or to fall under the force of such harmless weapons.

While the controversies continued, Howard University made progress in fulfilling its mission including educating women as well as men. This brief news item was published by the Farmer’s Cabinet.

A young colored lady has commenced the study of law in the law department of Howard University, in Washington. This is said to be the first instance of any colored lady pursuing the course of legal studies in this country.

This woman was the contemporary of emancipated slaves and descendants of enslaved ancestors, all people who were forbidden to learn to read or write. Her matriculation was an extraordinary event however economically reported. The Idaho Statesman of Boise identified this pioneer as “Miss Charlotte E. Ray, daughter of the Rev. Charles B. Ray.”

There were formidable challenges to the professional aspirations of young Black men and women. While the “colored lady” had just matriculated at the law department, the medical department was confronted with adamant racism by the American Medical Association (AMA) as reported on May 3, 1870, by the Albany Evening News. The AMA had refused the credentials of Howard University and the medical department of Georgetown College among others “because they permit consultations with colored physicians, even though they are regularly graduated.”

And yet, they persisted. The Weekly Louisianian reported on August 6, 1871, that

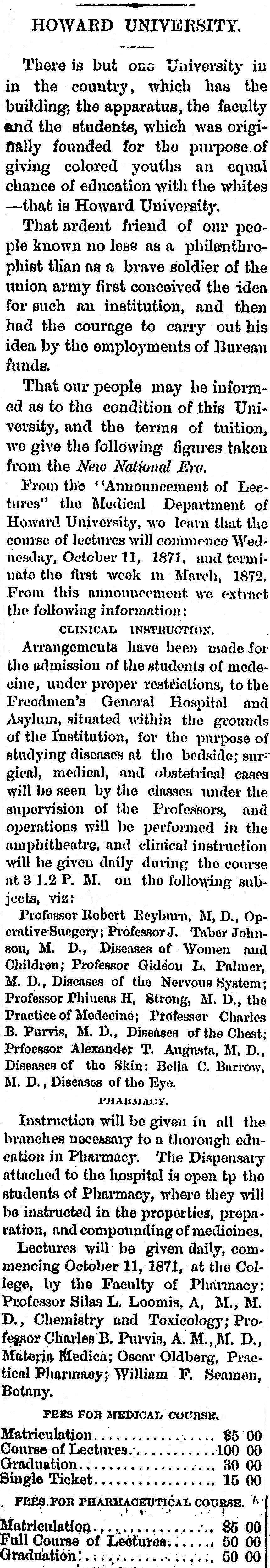

There is but one University in in [sic] the country, which has the buildings, the apparatus, the faculty and the students, which was originally founded for the purpose of giving colored youths an equal chance of education with the whites—that is Howard University.

The article provides information on the Medical department of Howard University, including the course of study, the faculty, and the fees. Despite the AMA, Howard would and did educate Black physicians.

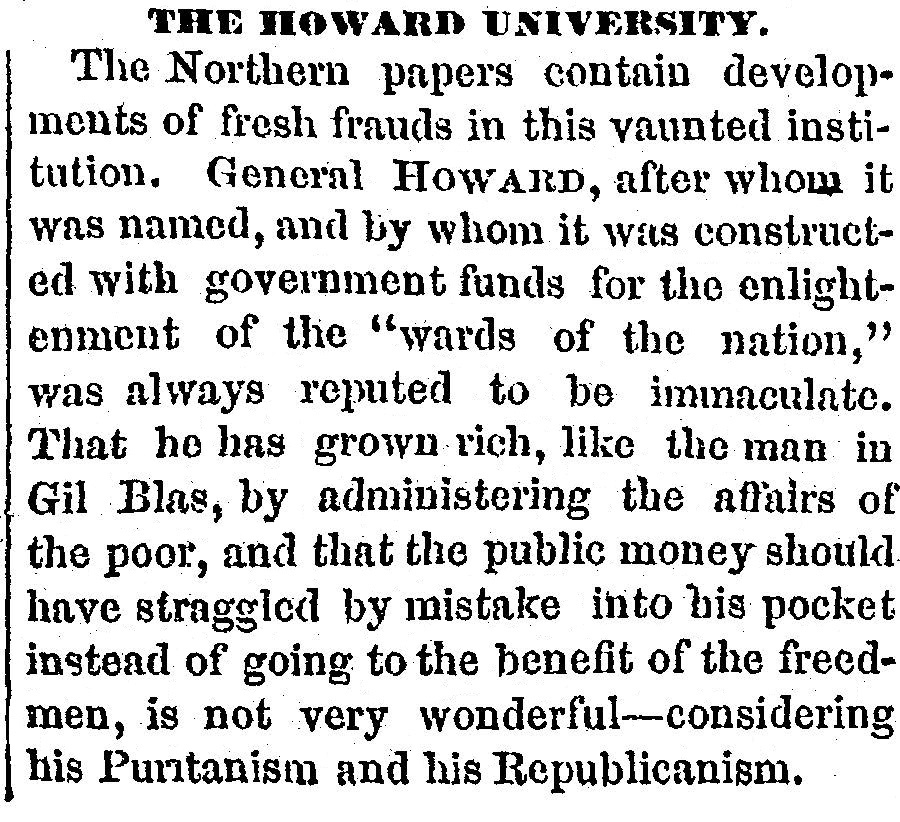

Southern newspapers seemed eager to print any accusations of malfeasance that discredited the university. One of many similar articles appeared on June 27, 1873, in the Richmond Whig.

The Northern papers contain developments of fresh frauds in this vaunted institution. General Howard, after whom it was named, and by whom it was constructed with government funds for the enlightenment of the “wards of the nation,” was always reputed to be immaculate. That he has grown rich, like the man in Gil Blas, by administering the affairs of the poor, and that public money should have straggled by mistake into his pocket instead of going to the benefit of the freedmen, is not very wonderful—considering his Puritanism and his Republicanism.”

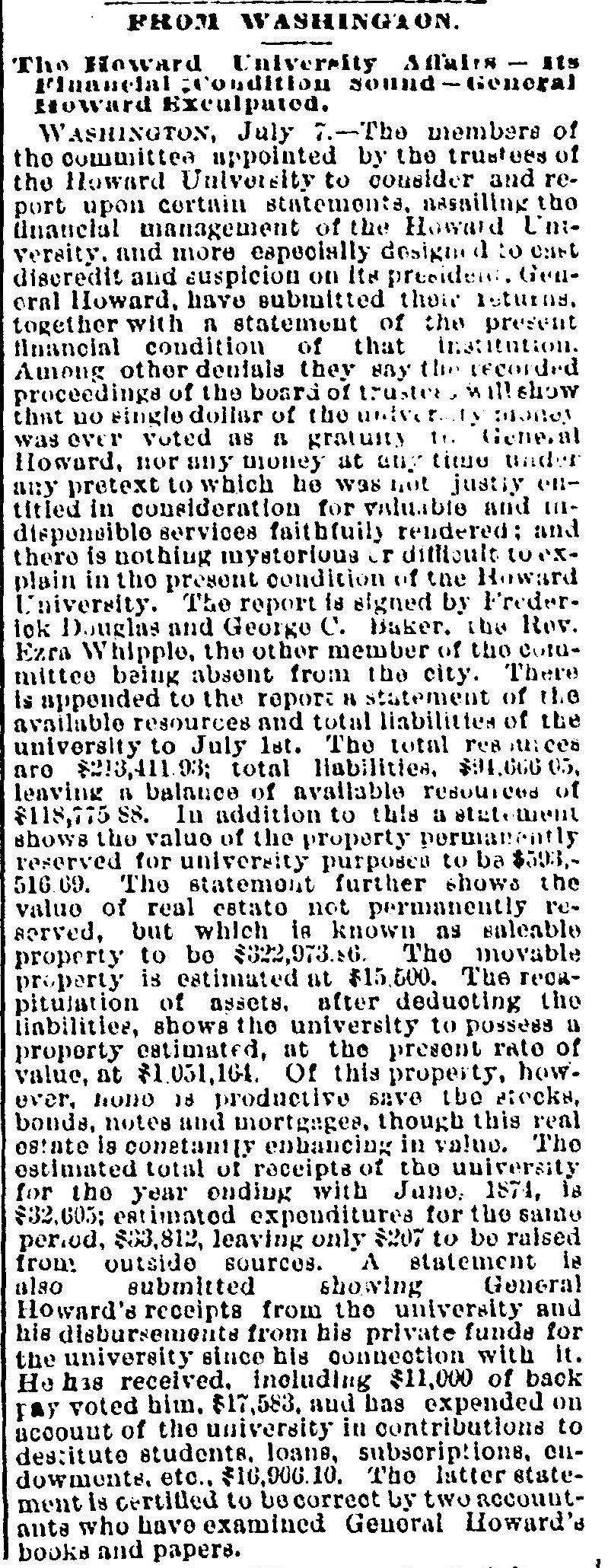

Shortly later the Hartford Daily Courant ran the headline “From Washington. The Howard University Affairs—Its Financial Condition Sound—General Howard Exculpated.” The article concluded:

A statement is also submitted showing General Howard’s receipts from the university and his disbursements from his private funds for the university since his connection with it. He has received, including $11,000 of back pay voted him, $17,583, and has expended on account of the university in contributions to destitute students, loans, subscriptions, endowments, etc., $16, 906.10. The latter statement is certified to be correct by two accountants who have examined General Howard’s books and papers.

Still, critics promoted false narratives about the general and the university. The Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner in Prescott was arguing in late 1873 that the enterprise was corrupt and doomed.

As might be supposed, the University is not in a healthy condition. In a few years there will be no inducement for “humanitarians” to take an interest in it—the bones will be picked lean and the wretched fraud will fall to the ground, another illustration of the cussedness of “christian” [sic] statesmen and “christian” [sic] generals.

Howard resigned as president in 1874. On June 18, 1875. the New York Evening Post published a laudatory article on the university and its founder. The praise is fulsome, the optimism palpable, the argument sound—if somewhat tainted by a misunderstanding of the lives of Blacks in the North.

The Howard University is doing the very noblest and best work it can do—taking the negroes from the South, ignorant and benighted, and returning them to the South instructed and trained. The negroes of the North are well enough; they live in prosperity and light. But it is to those of the old rice swamps and cotton fields, to the children of the gray-headed slaves, that this college calls. Its white walls shine like a beacon on a hill to them in their darkness, and its doors are wide that many may enter. But for those so poor that they needs must wait on its threshold, let their people, their friends, their government must provide; for not at the ballot-box, but in the schoolroom can the problem of the races be peacefully solved. Enfranchisement gave them sudden liberty; by education alone can they maintain permanent equality.

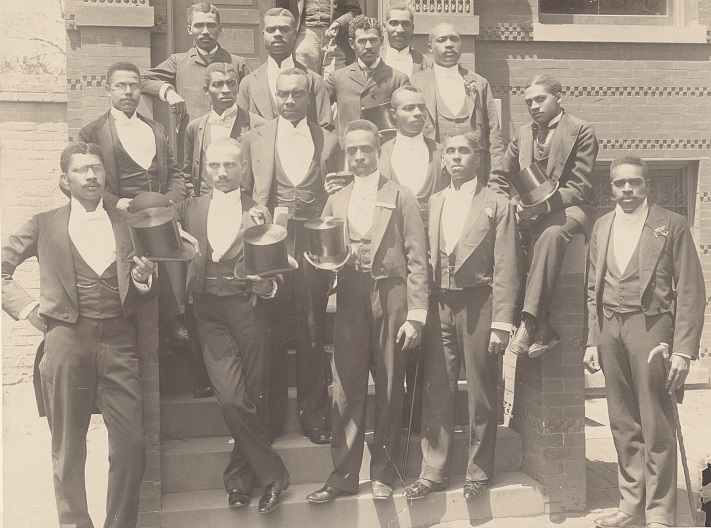

Howard University survived and prospered. Thousands of her graduates have achieved prominence based on their accomplishments. To name just a few; Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, Vice President Kamala Harris, Congressman Elijah Cummings, Mayor David Dinkens of New York, Senator Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, Nobel Prize awardee Toni Morrison, author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston, five-time Grammy Award winner Roberta Flack, and Academy Award-nominee Chadwick Boseman (for whom Howard University last month renamed its College of Fine Arts). Whatever his flaws, General Howard, who appears to have been an honorable and compassionate man, had a vision which has been sustained by generations of accomplished graduates.