The Early Histories of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Part II: Fisk University and the Jubilee Singers

Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee opened on January 9, 1866 more than year before Howard University. While Howard was beset by controversy from its beginning, Fisk seems to have had a considerably less fraught launching. Originally named Fisk Free Colored School, it was established by members of the American Missionary Association which was supported by the United Church of Christ which included the Congregationalists. The eponymous name of the new school was in honor of an assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, Clinton B. Fisk, who provided an abandoned military barracks and a $30,000 endowment. Unlike Howard University, Fisk did not rely on continuing federal funding. The need for financial assistance was great and led to the establishment of the Fisk Jubilee Singers and their astounding role in securing the future of the university.

By 1871 when Fisk was perilously close to bankruptcy, the treasurer and director of music, George Leonard White, created a small group of talented student singers and musicians for the purpose of touring the country and giving concerts to earn money for the university. They began their first tour in October of that year.

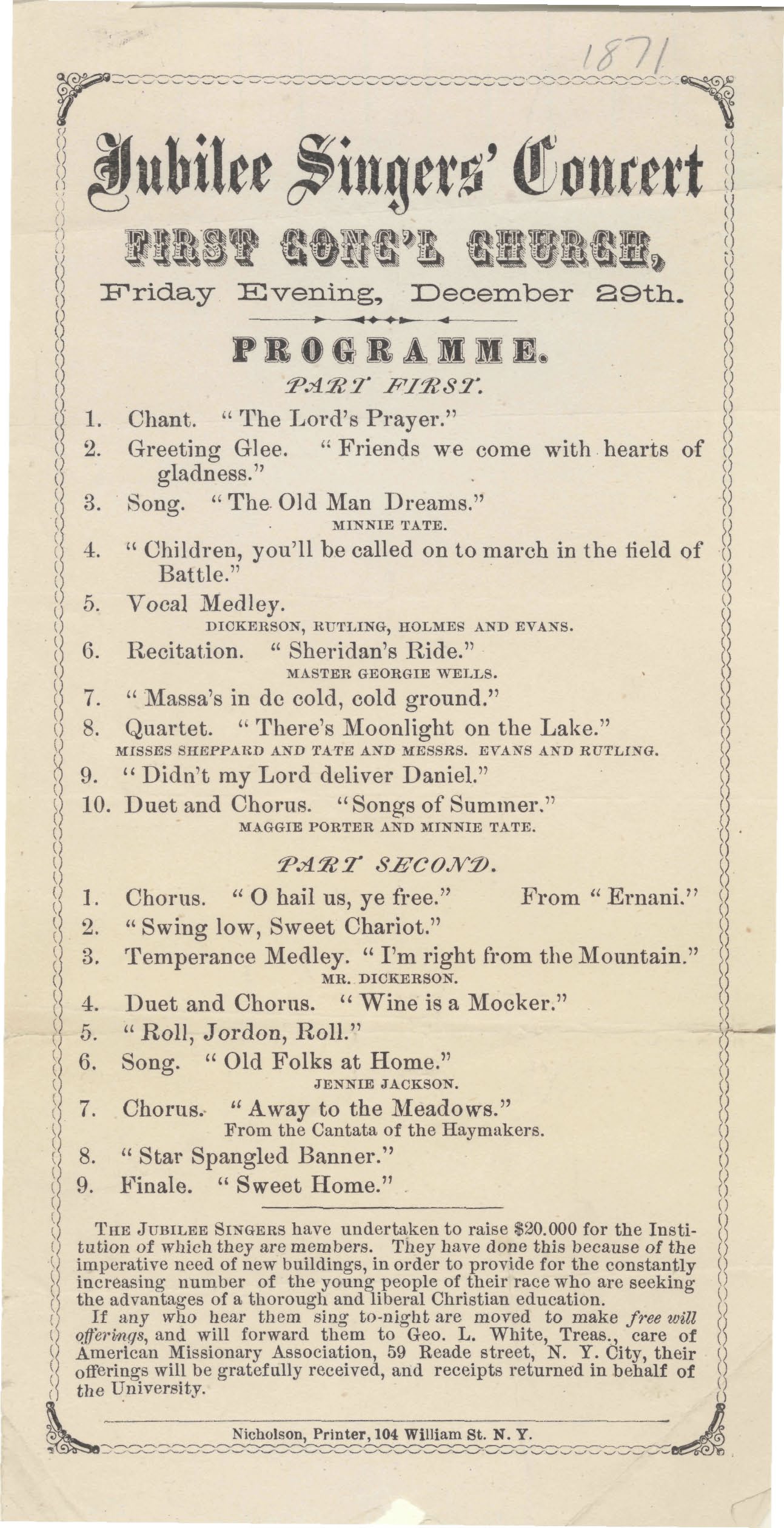

On December 29th they performed at the First Congregational Church in New York City. The program includes a statement of purpose:

The Jubilee Singers have undertaken to raise $20,000 for the Institution of which they are members. They have done this because of the imperative need of new buildings, in order to provide for the constantly increasing number of the young people of their race who are seeking the advantages of a thorough and liberal Christian education.

If any who hear them sing to-night are moved to make free will offerings, and will forward them to Geo. L. White, Treas., care of American Missionary Association, 59 Reade street [sic], N. Y. City, their offerings will be gratefully received, and receipts returned in behalf of the University.

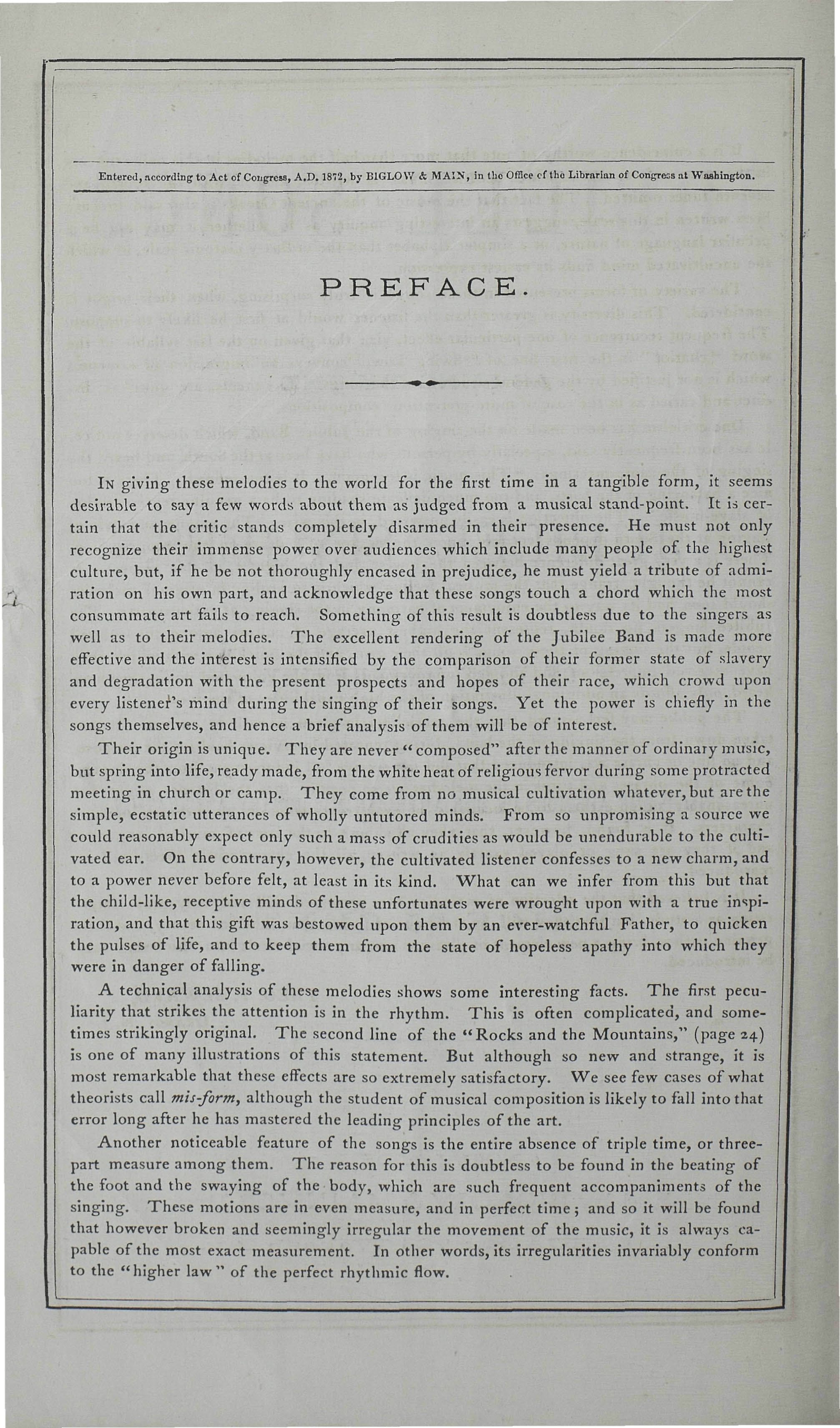

The performers specialized in what were originally called slave songs and later, Negro spirituals or plantation songs. A pamphlet published in 1872 includes a preface written by Theodore F. Seward who became a significant force in the astonishing success of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. This preface analyses the unique music of the enslaved people and begins by asserting that:

It is certain that the critic stands completely disarmed in their presence. He must not only recognize their immense power over audiences which include many people of the highest culture, but, if he be not thoroughly encased in prejudice, he must yield a tribute of admiration on his own part, and acknowledge that these songs touch a chord which the most consummate art fails to touch.

In short, the music was unique. It sprang from untutored people who sought solace and hope in their enslaved suffering with the spontaneous creation of music which had never been heard before. The Singers toured the northeast for eighteen months and garnered rave reviews as they progressed. At times the language used in these accounts can be disconcerting to our contemporary ears. It is important to consider the times and the fact that until 1865 these young men and women had been held in bondage, usually forbidden to learn to read and write. They were not savages but had been treated savagely. In less than a decade they had achieved something like a miracle.

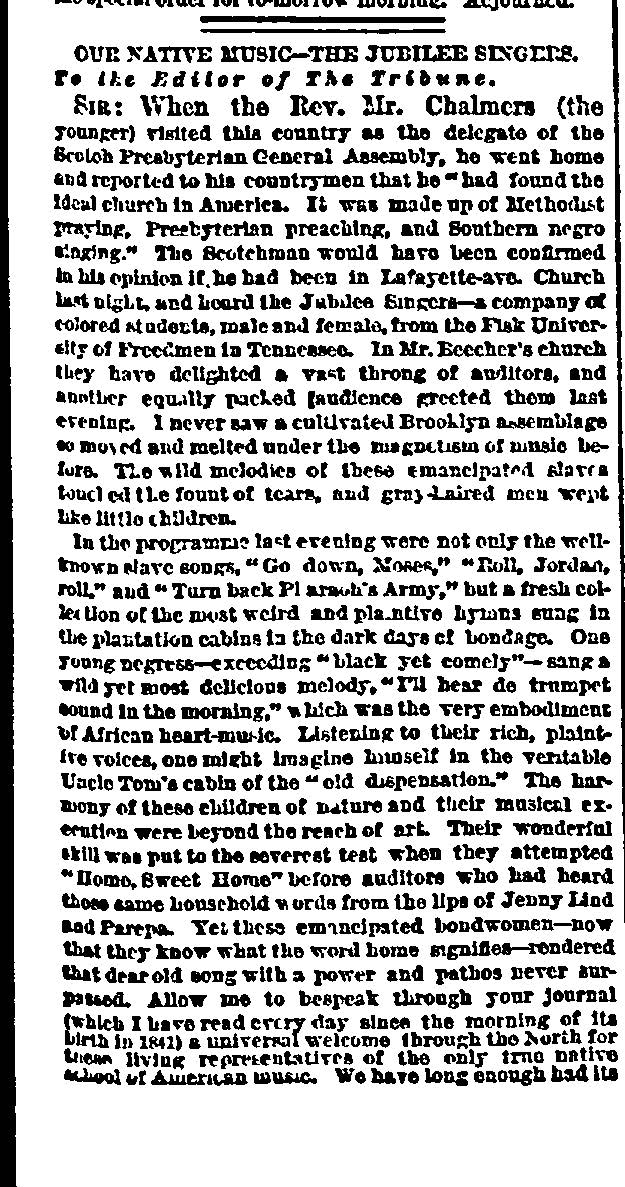

On January 19, 1872 the New York Tribune published just such a review in a letter to the editor titled “Our Native Music – The Jubilee Singers.”

In Mr. Beecher’s Church they have delighted a vast throng of auditors, and another equally packed audience greeted them last evening. I never saw a cultivated Brooklyn assemblage so moved and melted under the magnetism of music before. The wild melodies of these emancipated slaves touched the fount of tears, and gray-haired men wept like children.

In the programme [sic] last evening were not only the we;; known slave songs, “Go down, Moses,” “Roll, Jordan, roll,” and “Turn back Pharaoh’s Army,” but a fresh collection of the most weird and plaintive hymns sung in the plantation cabins in the dark days of bondage. One young negress – exceeding ‘black yet comely’ – sang a wild yet most delicious melody, ‘I’ll hear de trumpet sound in the morning,’ which was the very embodiment of African heart-music… The harmony of these children of nature and their musical execution were beyond the reach of art. Their wonderful skill was put to the severest test when they attempted ‘Home, Sweet Home’ before auditors who had heard Jenny Lind and Parepa. Yet these emancipated bondwomen – now that they know what the word home signifies – rendered that dear old song with a power and pathos never surpassed.

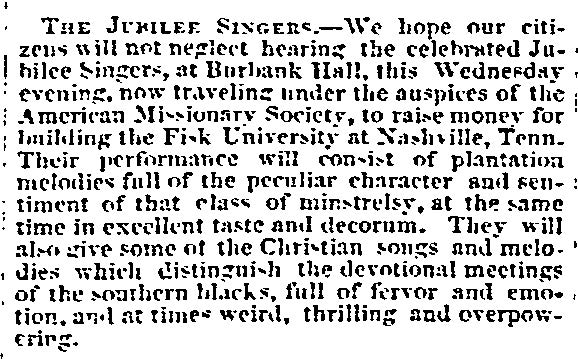

The Jubilee Singers performed in Pittsfield, Massachusetts in October of 1872. The Pittsfield Sun heralded their appearance on October 2nd.

Their performance will consist of plantation melodies full of the peculiar character and sentiment of that class of minstrelsy, at the same time in excellent taste and decorum. They will also give some of the Christian songs and melodies which distinguish the devotional meetings of the southern blacks, full of fervor and overpowering.

One of Fisk’s most distinguished graduates would be W.E.B. Du Bois who was born a free black in Pittsfield in early 1868. It is perhaps idle yet interesting to speculate that his parents may have taken the young boy to the concert.

During their eighteen-month tour the Jubilee singers achieved such fame that they were invited to the White House to sing for President Grant and to perform separately for Vice President Colfax. More important, they had raised the $20,000 which was their goal. (The buying power of one dollar in 1872 is the equivalent of $22.38 today.) In consequence of this success Gustavus D. Pike published a book in 1873 titled “The Jubilees Singers, and their Campaign for Twenty Thousand Dollars.” It is a compelling account of the early history of the group which includes biographies of the original members and photographs of them.

After the great success of their first tour, the Singers set out in 1873 on a second tour with the intent of doubling the returns. The New York Tribune again lauded their performance:

The songs which they brought us last night were almost without exception the songs which they brought with them out of servitude, - the rapturous hymn in which the oppressed used to chant the coming of the day of deliverance, the sad strains in which the suffering slave bemoaned his wrongs, the shouts of religious exaltation which resounded in the plantation camp=meeting. If the selections given on this occasion fairly represent the favorite subjects of the slave singers, the prevalence of a prophetic spirit among them, long before the dawn of freedom, is a very significant circumstance. The constant reference last night to liberation, in one form or another, must have struck every attentive listener. The mind of the verse maker seems to have been constantly upon the deliverance of Egypt out of bondage, and the singer was perpetually rejoicing in the [unclear] of ‘Old Pharaoh.’…Grotesque as this seems in print, not only the words, but in many of the musical phrases, there is nothing grotesque, there is even a grandeur and nobility in the song when one hears it from the lips of these children, who have in truth been delivered from a bondage that was worse than death.

By May of 1873 the Singers had arrived in England to begin their first European tour. The Salem Register of Massachusetts reported their arrival on May 22nd.

The Jubilee Singers from Fisk University, Nashville, Tenn., who sang in this city a few months ago are now in England, and are destined to produce a great sensation there. We have before us a copy of the London Telegraph of May 8, which, speaking of them, says ‘the London public will henceforth make the acquaintance of a troop of real negro minstrels, whose impressive musical performances are manifestly destined to take a prominent position among the most remarkable attractions of the present season… They are students connected with Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee, one of seven chartered institutions established by the American Missionary Association, ‘aiming to give the freedmen a higher and Christian education, so that the most gifted among them can be fitted to become the teachers and the leaders of their race in America, the West India Islands, and Africa.” They performed in London as guests of the Earl of Shaftsbury. “In the presence of a highly fashionable and critical audience, filling every portion of the space available, these negro vocalists with their simple minstrelsy produced an effect which not one among the assemblage is likely soon to forget. The hushed attention and the frequently moistened eye were perhaps to be regarded as more valuable tributes to the power they exercised than the unusually vehement plaudits which invited a repetition of nearly every piece set down in the programme… Yesterday afternoon they went to Argyll Lodge, and there performed before a distinguished arty, which included the Duke and Duchess of Argyll, the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland, and Dean Stanley. While the entertainment was proceeding the Queen came to the Lodge, and the Minstrels had the honour of singing several songs before her. He Majesty expressed gratification with what she heard.

Forty-three years later on April 10, 1916, Maggie Porter Cole who had been one of the ensemble which performed for Queen Victoria authored a remembrance for the Fisk University News. She wrote of her sweet memories with the Fisk Singers and her astonishment at first singing “in the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher’s church…”

Yes, and I think now I recall the day of all days, the day we appeared before Queen Victoria at Argyle Lodge, when we first saw the grandest and noblest queen of them all, under whose flag we knew thousands of our race had sought and found liberty in the dark days of bondage. And we felt, too, that we were having our first taste of real freedom where a man was ‘a man for a’ and a’ that.’ She was astounded that the queen “wore no crown, no robes of state. She was like many English ladies I had seen in her widow’s cap and weeds.” She further recounts performing for the emperor of Germany and family.

The tour was a financial success as reported by the Evening Post of New York City on May 27, 1874.

The well-known Jubilee Singers from Fisk University of Nashville, Tennessee, whose concerts in New York a year or two since were so satisfactory, have just returned from Europe, where their performances, as our readers already know, have been very successful, and have added $50,000 to the building fund of Jubilee Hall, now erecting at Nashville. Several thousand dollars were contributed by friends abroad in aid of the library and apparatus fund of the University.” At the close of their tour they performed in London again and were hosted by the Earl of Shaftesbury addressed the musicians. “I commend to you, young people, the deep sympathy we all feel, and our expression of affection and respect; we trust you may prosper in life and be happy in death.

An exhaustive account of the foreign tour was published in 1875 with the cumbersome title ‘The Singing Campaign for Ten Thousand Pounds; or, The Jubilee Singers in Great Britain. By the Rev. Gustavus D. Pike.’ The book is more than three hundred pages, but Pike provides many insights and details as a perusal of the table of contents will attest.

The Jubilee Singers had begun another tour in early 1875 visiting several northern cities culminating in a concert in New York preparatory to their embarkation for Great Britain. The Evening Post published a review on May 17, 1875:

At the Academy of Music last Friday night the Jubilee Singers gave a farewell concert, being about to return to Great Britain, where they intend to prosecute anew with redoubled exertions their endeavor to raise another large sum of money for the building of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee.

In 1876 the original Jubilee Singers was disbanded and reorganized. This news was conveyed in the notes accompanying their new programs.

This is the ORIGINAL COMPANY OF SINGERS which was organized from among the Students of Fisk University, in 1871, by Geo. L. White, then Treasurer and Business Manager of the University, to earn the funds for new grounds and buildings, imperatively needed to enable the University to continue its work… As the net results of their labors during the past eight years, a site for the University containing twenty-five acres, has been purchased, and Jubilee Hall built at a cost of over$150,000. About $15,000 was secured towards building Livingstone Missionary Hall, also a large amount of material for the University – money and books for the library, philosophical apparatus, musical instruments, furniture, specimen for the museum, paintings and other works of art, etc., aggregating many thousands of dollars in value.

On the return of the Jubilee Singers from Germany, the company was disbanded.

It has been decided by the American Missionary Association, and the Trustees of the University, the work of the Singers in their behalf is completed; that they cannot assume the responsibility of continuing this agency. The Singers being thus without employment, and the demand for their re-appearance in the Concert field being so general, they have been led to reorganize the company, hoping thereby to ‘get a living.’

In appearing before the public in this new capacity, they will be able to respond to requests which, owing to the urgency of need of Fisk University, they were compelled to deny before, and arrangements can now be made for concerts on terms which will enable local benevolent objects to share in the proceeds of their work.

The Singers had been warmly treated in Great Britain and never refused accommodations or service at meals. However, they had repeatedly been denied these basic needs in some American cities. The Daily Inter Ocean of Chicago published an article, The Jubilee Singers and the Hotels, on April 20, 1881.

It will be well to ascertain precisely the attitude of the hotel proprietors of Springfield [Illinois] toward the Fisk troupe of Jubilee Singers before unconditional condemnation is indulged in, for, according to a special in THE INTER OCEAN of yesterday, they deny that they refused accommodations to the troupe; but when the facts are fully known, THE INTER OCEAN will ask the public to note them and govern itself accordingly. The proprietors of the Leland House deny that application for rooms was made to them, notwithstanding Mr. Cushing, the agent of the troupe, says explicitely [sic] that he met both Leland and his business manager, and that the refusal was flat-footed and positive. The other hotels explained that they had engaged all their rooms to Robinson’s Circus for the days on which the Jubilee Singers required them, and were, therefore, compelled to refuse. It has come to this, then, that the visit of a circus to the capital of Illinois so completely overwhelms the hotels that there are no accommodations for a dozen people who may desire to visit the place the same day… When the truth is reached, however, it will undoubtedly come to this as the final explanation: The troupe is composed of colored men and women; some of the gorgeous patrons of the 7x9 taverns at Springfield… look down upon the ’nigger,’ and would have their autocratic feelings shocked if this troupe was lodged and paid their bills under the same roof. The members of the troupe are educated, and able to pay their way – the men who object to them are, ten to one, ignorant, and do not often indulge in the luxury of a hotel even of the kind they have in Springfield. But they are white, in color at least, and so those who are more than their peers in every other respect are treated shabbily to spare the delicate sensibilities of these superior beings.

The Fisk Jubilee singers have traveled abroad, and have been treated with the distinguished consideration which their talents merit… They have stopped at the principal hotels in Europe and America, and in Chicago would have no difficulty in securing accommodations at any of the great palaces for which the city is famous. It is only when they strike a fourth rate town, with dingy hotels and superstitious landlords, that they are refused the ordinary hospitality extended to people of half their brains and gentility.

Despite the occasional indignities to which the Singers were subjected, they continued to tour at home and abroad. Throughout the years the members changed as did the organization, but its mission continued to provide financial support to their beloved university. This year marks the 150th Anniversary of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. In 2021 they recorded an album to celebrate their sesquicentennial titled, “Celebrating Fisk! The 150th Anniversary Album"—it won the Grammy® Award in the Best Roots Gospel Album category.