'Forwarded as Merchandise': News Coverage of Henry Box Brown’s Remarkable Quest for Freedom

As an enslaved man, Henry Brown’s experience was not atypical; he was allowed to marry and have children, but as human property he and his family could be permanently separated from each other on a slaveholder’s whim. His escape from slavery, however, was anything but typical. Details of Brown’s life prior to his quest for freedom were recounted in this 1859 article published by the Boston Republican and reprinted in the New Hampshire Farmer’s Cabinet.

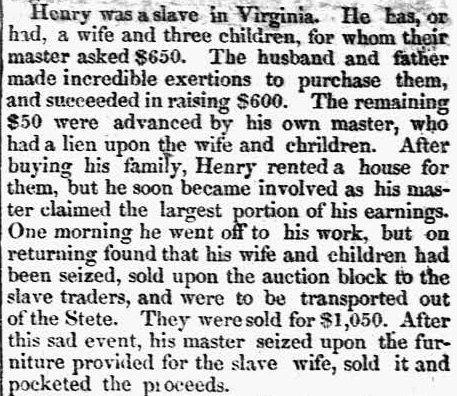

Henry was a slave in Virginia. He has, or had, a wife and three children, for whom their master asked $650. The husband and father made incredible exertions to purchase them and succeeded in raising $600. The remaining $50 were advanced by his own master, who had a lien upon the wife and children. After buying his family, Henry rented a house for them, but he soon became involved as his master claimed the largest portion of his earnings. One morning he went off to his work, but on returning found that this wife and children had been seized, sold upon the auction block to the slave traders, and were to be transported out of the State. They were sold for $1,050.

The article continued:

When the master, noticing his despondency, told him he could get another wife—southern morality—Brown shook his head,—the wife of his affections and the children of his love, or none at all.

Thoughts of liberty now began to spring up in his bosom. He had heard of the abolitionists, and determined to escape to them if it was possible.…The means used for escape were of the most unprecedented character. With the assistance of a friend, arrangements were made for him to escape in a box, which was to be forwarded to friends of the slave in Philadelphia, carefully marked as a valuable package.

The New York Evening Post covered Brown’s story under the headline, “The ‘Running’ of Slaves,” and detailed the small size of the box in which Brown was shipped.

At the anniversary meeting of the Anti-Slavery Society of Boston, on Wednesday, Brown, the fugitive slave, whose extraordinary escape from servitude in Richmond, and almost miraculous arrival at Philadelphia, created such a sensation about two weeks since, was introduced to the audience. He was actually transported three hundred miles through a slaveholding country and by public thoroughfares, in a box, by measurement, exactly three feet one inch long, two feet wide and two feet six inches deep.

The Norfolk Democrat also recounted Brown’s escape, writing on page one:

One of the most thrilling events of the week was the appearance of the heroic man who so recently escaped from slavery in a box, marked and forwarded as Merchandise, from Richmond to Philadelphia. The warmest sympathies of the people were enlisted in his behalf. His story is one of thrilling interest. Every generous heart will be touched by the recital; whenever and wherever that story is told it will arouse the sympathies of mankind, not only for Henry Box Brown, but for his oppressed race. Shame on Virginia, that one of her sons should thus be compelled to act and suffer to gain the rights which belong to our common humanity. She proudly claims to be mother of statesmen and heroes, but not one of hers ever gave greater evidence of heroism than this poor despised son of hers. And this act of heroism was not made for her defence, but it was made in escaping from her bosom.

Additional details about Brown’s odyssey while in the box en route to Philadelphia are also found in The Evening Post’s article:

While at Richmond, though the box was legibly and distinctly marked “this side up with care,” it was placed on end, with his head downwards. He felt strange pains, and was preparing himself to die, preferring liberty or death to slavery, and he gave no sign. He was, however, relieved from this painful position, and encountered no other danger than the rough handling of the box, until it arrived in Washington. When the porters who had charge of it reached the depot there, they threw or dropped it with violence to the ground, and it rolled down a small hill, turning over two or three times. This he thought was bad enough, but the words he heard filled him with anguish and brought with them the blackness of despair. They were, that the box was so heavy it could not be forwarded on that night, but must lay over twenty-four hours. In the language of the fugitive, “My heart swelled in my throat; I could scarcely breathe; great sweats came over me; I gave up all hope.”

Brown turned to prayer.

“While I was yet praying, a man came in and said, ‘that box must go on; it’s the express mail.’ Oh, what relief I felt. It was taken into the depot, and I was placed head downwards again for the space of half an hour. My eyes were swollen almost out of my head, and I was fast becoming insensible, when the position was changed.”

He arrived in Philadelphia after many hair-breadth ‘scapes, and the box was taken to the house to which it was directed. The panting inmate heard voices whispering; afterwards more men came in. They were doubtful or fearful about opening the box. He lay still, not knowing who the people were. Finally, one of them knocked on the box, and asked, “Is all right here?” “All right,” echoed from the box. The finale of this simple tale was received with deafening shouts.

Brown, nicknamed “Box” at an antislavery convention later that year, gained further renown as a speaker for the Anti-Slavery Society and for his autobiography, Narrative of Henry Box Brown. After the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was passed an attempt to capture him was made. The New Hampshire Sentinel reprinted this short news item from the New Bedford Mercury:

ATTEMPT TO KIDNAP HENRY BOX BROWN.—An attempt was made on Henry Box Brown, the fugitive slave, in Providence, on Friday, by some men, whose purposes were not fully disclosed. We are told that Mr. Brown was twice attacked, while walking peaceably through the streets, and that one time the attempt was made to force him into a carriage. He proved too strong for them. His friends think the object was to get him on board a vessel bound to Charleston, or dispose of him Southward, in some other way.

Reporting from the police record in the Providence Post, the New Hampshire Sentinel article added:

Thomas Kelton was fined $15 and costs for an assault on Henry Box Brown. Appealed.

It appeared, in evidence, that Henry was passing quietly up Broad street on Friday afternoon, when he was attacked by Kelton and others, and severely beaten, without any known cause.

Shortly after this attack Brown moved to England where he would marry, begin a new family, and perform as a magician and conjurer. The Norfolk Democrat’s article on his greatest trick of all, disappearing from enslavement in Richmond, concluded with this challenge to its readers:

Let each of us, as we read [Brown’s story], remember that three millions of our race are held in bondage, by the same laws which this poor man risked so much to escape from.—Let each one of us, then, firmly resolve to exert all the political and moral influence we possess, to free the country from the curse and shame of slavery. Let us now, that come what may, we will never cease our efforts until every slave in our country can stand up in the dignity of manhood and say, “I am a man and a brother.”

Further news coverage of Henry Box Brown can be found in Black Life in America, a new online resource for studying the experience and impact of African Americans from 1704 to today. Other notable people covered in this database’s extensive news reporting from the antebellum era include William Wells Brown, Ellen Craft, Solomon Northup, Sojourner Truth and many others.