Freedom Bound: The Sesquicentennial of the Emancipation Proclamation

By Erica Armstrong Dunbar, Associate Professor of History, University of Delaware, and Director of the Program in African American History, Library Company of Philadelphia

In 2013, people across the United States will celebrate the sesquicentennial of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. As the country approached a third year of bloody civil war, President Abraham Lincoln issued what has become the most symbolic of mandates. Although limited in many ways, the Proclamation stands as a centerpiece in the long struggle to end racial slavery in America, an institution that spanned more than two centuries and brought death and despair to millions of people of African descent. Most Americans understand the connection between freedom and the Emancipation Proclamation, remembering the document’s famous wording that “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free...” Many people mistakenly assume the executive order granted freedom to all African Americans. In actuality, the Proclamation only offered freedom to those slaves who resided within the southern states that had seceded from the Union and joined ranks with the Confederacy. While the Proclamation did, in theory, “free” approximately three million slaves, it left more than one million African Americans trapped in the “peculiar institution” in border states such as Delaware and Kentucky. The year prior to the drafting of the Emancipation Proclamation was a difficult one for Abraham Lincoln. He watched his country sink deeper and deeper into a war that many originally thought would last only a few weeks. Many Union soldiers lost their lives on the battlefields and in the camps where disease and infection killed tens of thousands of soldiers. The price of war was high, and as Southerners appeared to be gaining on victory, Abraham Lincoln and his advisors were forced to think of new strategies to help bring a Union triumph into sight. In July of 1862, President Lincoln crafted a preliminary Proclamation, one that offered rebel Confederates a chance to end the war or risk losing their most valued property—their slaves. Housed at the Library Company of Philadelphia is a draft of this Proclamation dated July 25, 1862. The Proclamation is a part of the Library Company’s Afro-Americana Collection, which contains over 13,000 titles and almost 1,000 graphics. One of the largest collections of early African American life, this collection, acquired by the Library Company over the course of more than two centuries, features documents related to the western discovery and exploitation of Africa, the rise of slavery in the new world along with the rise of movements against slavery, the development of racial thought and racism, descriptions of African American life, and the printed works of African American individuals and organizations. The collection, which ranges in date from the mid-16th century to the early years of the 20th century, is in the process of being digitized.

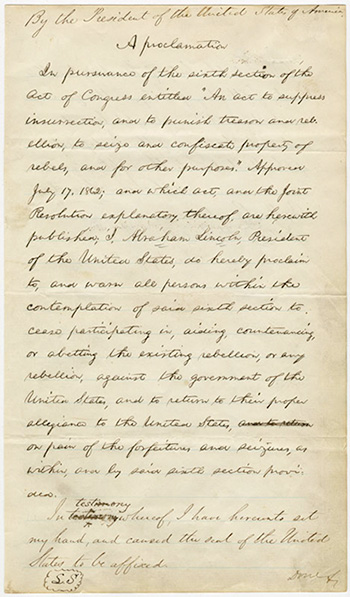

Abraham Lincoln, A Proclamation. Manuscript, 1862 (Source: Library Company of Philadelphia). The July draft of the Proclamation quite clearly offers the rebels an ultimatum, mandating soldiers to cease from rebelling or risk forfeiture of their property. It is clear that President Lincoln’s handwritten draft focuses upon their most valued property: slave men and women. Unsurprisingly, the draft Proclamation was written a little more than a week after the passage of the Second Confiscation Act, a legislative action that gave the military and civilians within the Confederate states a sixty-day notice of surrender. If the Act was ignored, property—including slaves—was to be confiscated. The Second Confiscation Act and the Militia Act also gave the president the authority to recruit black men for the Union army. Lincoln expected that thousands of slaves would continue to flood the Union camps as northern troops moved across the South. Although Lincoln had refused the participation of willing black soldiers at the beginning of the war, he reversed course out of necessity. Over 180,000 African American men offered their service to the Union army. Although they were often used to perform grueling physical and menial labor instead of active duty, there was a strong desire by many black men to join the Union army. From the outset of the war abolitionist Frederick Douglass argued in favor of allowing black men to serve their country. To Douglass, black participation in the military would not only assist the North in winning the war, but would also advance the cause of equal rights. Following the Emancipation Proclamation, advertisements were created to entice black men to enlist in the Union army. One such advertisement is also housed in the Afro-Americana Collection. A well-known Union recruitment poster, United States Soldiers at Camp “William Penn” Philadelphia, PA, was printed in 1864 as way to attract young black men to join the military. The striking image of uniformed black men, disciplined in their appearance and their cause, was attractive to African Americans throughout the north who often found it close to impossible to survive on meager earnings. The military offered wages, food, and clothing, albeit inferior to the earnings of white soldiers. The recruitment poster also emphasized the obligations of black men to fight in a war that had at its center the struggle to end the institution of slavery. A free or fugitive black man could take pride in fulfilling a duty to his nation, while ending the system of slavery that held his friends and family in bondage.

P.S. Duval & Son, United States Soldiers at Camp "William Penn" Philadelphia, PA: "Rally Round the Flag, Boys! Rally Once Again, Shouting the Battle Cry of Freedom" (Philadelphia: Published by the Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments, 1210 Chestnut Street), 1863. Chromolithograph with hand-coloring. (Source: Library Company of Philadelphia)

2013 will most certainly shine a light upon the events surrounding the Emancipation Proclamation. Free and open to the public, the Library Company of Philadelphia invites all who are interested to visit and lose themselves in the treasures of the Afro-Americana Collection. Academic institutions interested in making the digital edition of this collection available to their own faculty and students should contact Readex directly. About the Author: Erica Armstrong Dunbar is an Associate Professor of History with joint appointments in Black American Studies and Women's Studies. She received her BA from the University of Pennsylvania and her MA and Ph.D. from Columbia University. Her first book is A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City (Yale University Press, 2008). She has recently participated in several documentaries, including "Philadelphia: The Great Experiment" and an upcoming episode of "American Experience" on PBS. In 2011, Professor Armstrong Dunbar was appointed the first director of the Program in African American History at the Library Company of Philadelphia. She has been the recipient of Ford, Mellon, and SSRC fellowships and most recently has been named an Organization of American Historians Distinguished Lecturer. Professor Dunbar's newest book project is entitled "Never Caught: The Life of Oney Judge Staines." Work Consulted: Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton, 2010). John Hope Franklin & Evelyn B. Higginbotham, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans (New York, McGraw-Hill, 2010). James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York, Oxford University Press, 1988). Editor's Note: This post first appeared in the September 2012 issue of The Readex Report.