Hetty Green, “Financial Amazon” of the Gilded Age

At the southern edge of the picturesque village of Bellows Falls, Vermont, stands a modern TD Bank building. Erected on the site of the former home of Hetty Green, it’s a fitting tribute to the richest woman investor of her day who owned banks, railroads, mines and much else besides. When Mrs. Green passed away in 1916 at the age of 81 she left to her children Edward and Sylvia an estate worth upwards of $100 million dollars. Adjusted for inflation that would be about $2.4 billion dollars in 2020. That’s serious money for the “financial Amazon” who took money very seriously, which engendered grudging respect and fear from the “sharks of Wall Street.”

Mrs. Green, the financial Amazon who has proved herself a match for the schemers and sharks of Wall Street, who occasionally engineers mysterious movements there, who has several times put the bears to rout in corners on Reading, in which her clutch on the throats of unfortunate shorts was none the less strong because it was that of a woman’s jeweled hand, was really the cause, it has always been held, of the failure of John J. Cisco’s Sons, the bankers, last year.

She chose Bellows Falls as her home in part because her estranged husband’s family came from that place. Until her final years it was little more than an address where taxes on her sizable holdings were low relative to most other places she lived and visited. To avoid both taxes and uninvited callers she otherwise stayed in a steady succession of inexpensive boardinghouses, never remaining in any one place long enough to establish legal residency. She typically subsisted out of her reticule, a cloth drawstring bag common in the nineteenth century. When she died she was buried in an unmarked grave in her husband’s family plot. Her name has since been added to the monument there, and also graces a small park nearby.

Hetty Green is not widely recognized today because although she had a genius for making money, she was highly averse to spending it. Another building in Bellows Falls bears ironic testimony to her parsimonious sensibility. The Rockingham Free Library just south of Green’s former home is a Carnegie library, built with funds from the industrialist Andrew Carnegie. And well that it was financed by Carnegie, for when the library trustees approached Mrs. Green for support she sent them packing empty-handed.

Some years ago when Andrew Carnegie was in the height of his library distribution, Bellows Falls was brought to his attention, with the result that he promised to supply the funds for the building if the town would provide the site. Hetty Green’s riches and the excellent position of her property on Church Street were all taken into consideration by the library committee. One bright morning they called en masse upon the richest woman in the world to ask for the contribution of the site or its sale.

After about three minutes, it is said, the committee filed out of the front door, replaced their hats and thereafter avoided conversation on Hetty Green and the library.

In her defense Mrs. Green was at least as severe with herself as she was with others, and she was regarded as scrupulously honest in her business dealings. Henrietta “Hetty” Robinson was born in 1834 in New Bedford, Massachusetts, to Quaker parents who modeled simplicity and thrift. Her father Edward was prominent in whaling at the peak of that trade; her mother Abby died when Hetty was in her mid-20s. Because of family tensions Hetty was raised primarily by her unmarried Aunt Sylvia and her grandfather Gideon. She learned her business skills in part by reading the financial sections of newspapers to her father and grandfather in their old age. She also absorbed their habits of restraint in matters of personal indulgence.

“My father,” said Hetty one time when she had become a financial power, “taught me never to owe any one anything, not even a kindness.”

Once she saw her father decline a 10-cent cigar that was offered to him by an acquaintance. When the man pressed him to accept, knowing him to be a user of tobacco, Black Hawk Robinson gave a frank reason for his refusal.

“I smoke four-cent cigars and like them,” he said. “If I were to smoke better ones I might lose my taste for the cheap ones that I now find quite satisfactory.”

When both her father and Aunt Sylvia died in the summer of 1865 Hetty received over seven million dollars from their estates, much of the amount left in trust. She fought with mixed success to have the wills adjusted more in her favor. She was thoroughly convinced that her father was killed by jealous rivals, a belief that may have contributed to the distance she maintained from polite society.

One habitué of polite society whose company she did suffer was Edward H. Green, a millionaire in his own right and over a dozen years Hetty’s senior. And Green had something besides his money and seniority to recommend him—he had Hetty’s father’s blessing to marry her. Initially she was by no means averse to the match although she would later live apart from her husband when he lost his fortune and used hers as collateral without her permission.

In partial explanation of her reclusiveness, one can readily imagine that Mrs. Green would constantly have been approached by reporters, speculators, gold-diggers and all manner of “cranks.” For example, at least one young man claimed to possess more than a foolproof scheme for cornering the market—he claimed to be her son. He called upon her at a Brooklyn hotel to present his claim, sending up a card with his name on it.

Mrs. Green was not in, and Mr. Green was in his room. After looking at the card, he told the bell-boy that he did not want to see the visitor. The bell-boy returned and reported this to the clerk. The boy was told to inform the visitor, but when he went into the sitting-room the man was gone. Mr. Niblo, the clerk, at once gave orders for a quiet search of the house. This resulted a few minutes later in the discovery of the man, who was crouching in the hallway beside Mrs. Green’s door. He was at once led downstairs and asked what he meant by his conduct. Instead of replying, he bluntly demanded a room. The register was pushed toward him, and, seizing the pen, he wrote: “Hetty Green’s son, Brooklyn.”

Mr. Niblo knew that the man could not be the son of the wealthy guest of the hotel, inasmuch as Mrs. Green’s only son, Edward, is in Texas. So the clerk sent for Colonel Tumbridge, the proprietor of the hotel. The Colonel quietly took the man by the arm and walked with him to the door. Just as the stranger reached the vestibule he tried to strike the Colonel, but one of the porters seized his arm. Another porter came to the rescue, and between them they took the man and swung him far into a deep snowbank in Orange St.

He jumped up again and attempted to re-enter the hotel. He was met by the head porter, who threatened to call a policeman. The word “policeman” seemed to terrify the man, and he went away.

Many of her social and financial peers found her extreme frugality off-putting, as Mrs. Green did not hew to the expectations of fashion, class or gender.

Mrs. Green dresses as comfortably as an industrious washerwoman, but no more fashionably. She wears her clothes until they are worn out, and by that time they are ready for the paper mill. She rides down town in a horse car, and may have with her $1,000,000 in bonds done up in a piece of newspaper. Nobody would ever suspect her of being worth 1,000,000 cents.

In many respects Hetty Green was in the feminist vanguard as she succeeded brilliantly on her own terms as a financier, a profession that was a bastion of male privilege. Her power became tangible (and deadly) when she was granted the rare privilege of carrying a gun in New York City for self-defense. And like a proper feminist iconoclast she was immediately criticized for her temerity and linked to other prominent women such as temperance advocate Carrie Nation and anarchist Emma Goldman. Worse, if Mrs. Green could carry a weapon, all women would desire to do so.

Then, to broaden the question, why, if Hetty Green and Carrie Nation are allowed to have deadly weapons concealed about their persons, may not Mrs. Astor, Nellie Bly and Emma Goldman ask and be granted the same privilege? Then, to go to logical limits, if certain women are given special permits, why should not all women have them? And why, if women have them should not men have them, too? This would put everybody into the little game of self-preservation, or taking care of number one, on exactly the same basis. The only thing New York would have to do in that event would be to declare martial law.

Hetty Green is entitled to no special favors in New York, the less so because it is notorious that she gets rid of paying large sums in taxation by asserting that her residence is in Vermont—a legal fiction. There could be no objection to her hiring a sturdy guard to see that no harm comes to her in dark alleys or unfrequented streets, but she should come squarely under the head of the political axiom, “special privileges to none.”

As a literal femme fatale, Green was harshly critical of women who accepted and traded upon their traditional role as the weaker sex. Among anecdotes published in The Trenton Times in 1903 were her lively comments on fashionable women:

With indignation and scorn mingled in her phrases, Mrs. Hetty Green sat in the witnesses’ room of the Supreme Court in Brooklyn one day last week, and talked about divorce.

Not that she was there in a divorce proceeding—the case in which she had been defendant and which she had won concerned money alone. But somebody told Hetty that in another court there were thirty divorce suits on Justice Marean’s docket, and she forgot finance for the moment while she flayed modern society.

“‘Divorce Day’, they call it,” she said. “Well, what can you expect? These women never learn to keep house. They get married and their sole ambition is to wear fine clothes, bleach their hair, wear gay ribbons and fine laces. Home is the last place they want to think of. They go parading round with their vulgar style and think they’re beauties. Poor things! They never get sense!” And she swung her faithful reticule in her virtuous wrath.

“Next thing the husbands go parading around, and then the trouble begins,” she continued. “Then they find themselves in court. That’s it! Oh, I’ve lived around in hotels and I know what these women are! The young folk of today haven’t inherited common sense. That’s the reason Justice Marean has that big calendar of divorce suits.”

An interesting counterpoint to Mrs. Green’s views is recorded in The Freeman of Indianapolis, Indiana, on September 12, 1908, wherein her criticism of “finery loving and frivolous femininity” provoked a response from Mrs. Belle de Rivera, “a prominent club woman.”

“The whole is greater than any part,” said Mrs. de Rivera. “This is the only reply I can make to Mrs. Green’s statements. It may be true that some women will stop at nothing to get clothes, but the percentage is very small. When one considers that more than 6,000,000 of women are earning their own living and have something more serious to consider than clothes, it is easy to see that Hetty Green’s ideas are grossly exaggerated.

“And if it is true that even a small percentage of women make clothes and extravagance their passion, who is to blame? The husbands, brothers and fathers who are martyrized by Hetty Green. Men give women nothing more to think about than clothes; they expect them to think of nothing else, and so long as they decorate their opera box and grace their table the husbands, fathers and brothers are satisfied.

So long as men regard women as nothing more than dummies upon which to hang their jewels and display their wealth to social and business competitors, they can expect to encounter extravagance—it is the price they are willing to pay.

Unsparing in her criticism, Green was also free with her advice as to how to get ahead:

“One trouble with many young men who start out in business is, they try to do too many things at once,” says Hetty Green, “the richest woman in America,” in the Ladies’ Home Journal. “The result is that they don’t know as much as they ought to about any one thing, and they naturally fail. The trouble with young men who work on salaries is that they’re always afraid of doing more than they are paid for. They don’t enter into their work with the right spirit. To get on and be appreciated, a young man must do more than he is paid to do. When he does something that his employer has not thought of, he shows that he is valuable. Men are always willing to pay good salaries to people who will think of things for them. The man who only carries out the ideas of another is nothing more than a mere tool. Men who can be relied upon are always in demand. The scarcest thing in the world to-day is a thoroughly reliable man.”

As fierce, independent and outspoken as Mrs. Green was, there were a few instances when she met her match. One such time occurred when she went to withdraw her entire holdings from John J. Cisco & Co., mentioned above, where she had maintained accounts for decades.

Mrs. Green at one time did business with the well-known New York banking house John J. Cisco & Co., and deposited with them her cash, bonds, securities and other forms of money, running into big figures. One day she went to the bank to express her dissatisfaction with the way some matter of hers had been conducted. Mr. Cisco, the head of the concern, argued the question with her in a temperate way, but her wrath was aroused and she would not be appeased. Finally she stated her intention of withdrawing from the bank, then and there, every sumarkee that stood to her credit. She said it with emphasis and not in the way of one who merely puts forth a bluff. Anyway, Mr. Cisco took her seriously and told her it would give him the greatest pleasure to accommodate her; that she should have every dollar that was hers on the spot, and straightaway ordered an employee to get out Mrs. Green’s gold and silver coin, greenbacks, treasury notes, stocks and bonds and all other kinds of lucre the lady possessed. The clerk was a good while at it, but he at length piled $5,000,000 or $6,000,000 in front of the owner, who had been regarding the task without comment.

“There’s your property, Mrs. Green,” remarked the old banker, “please remove it.”

“I have changed my mind and you can keep it.”

“Excuse me, madam, but we don’t care for your patronage any longer. Please take your money away.”

Old Cisco was deaf to all her pleadings to let the stuff stay. He was just as resolute as she had been wrathful, but he consented to let one of his men go out and buy a trunk to pack the cash and other financial tokens in, and then let the man accompany Mrs. Green and her trunk to another depository.

Another instance of Mrs. Green grappling with an equally hard-nosed businessperson appeared in the January 1, 1897, edition of The Owyhee Avalanche:

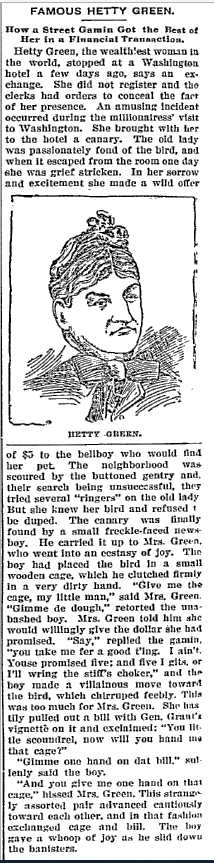

Hetty Green, the wealthiest woman in the world, stopped at a Washington hotel a few days ago, says an exchange. She did not register and the clerks had orders to conceal the fact of her presence. An amusing incident occurred during the millionairess’ visit to Washington. She brought with her to the hotel a canary. The old lady was passionately fond of the bird, and when it escaped from the room one day she was grief stricken. In her sorrow and excitement she made a wild offer of $5 to the bellboy who would find her pet. The neighborhood was scoured by the buttoned gentry and, their search being unsuccessful, they tried several “ringers” on the old lady. But she knew her bird and refused to be duped. The canary was finally found by a small freckle-faced newsboy. He carried it up to Mrs. Green, who went into an ecstasy of joy. The boy had placed the bird in a small wooden cage, which he clutched firmly in a very dirty hand.

“Give me the cage, my little man,” said Mrs. Green. “Gimme de dough,” retorted the unabashed boy. Mrs. Green told him she would willingly give the dollar she had promised. “Say,” replied the gamin, “you take me fer a good t’ing. I ain’t. Youse promised five; and five I gits, or I’ll wring the stiff’s choker,” and the boy made a villainous move toward the bird, which chirruped feebly. This was too much for Mrs. Green. She hastily pulled out a bill with Gen. Grant’s vignette on it and exclaimed: “You little scoundrel, now will you hand me that cage?”

“Gimme one hand on dat bill,” sullenly said the boy.

“And you give me one hand on that cage,” hissed Mrs. Green. This strangely assorted pair advanced cautiously toward each other, and in that fashion exchanged cage and bill. The boy gave a whoop of joy as he slid down the banisters.

Mrs. Green occasionally succumbed to extravagance herself. Before she came into her inheritance she convincingly played the role of society belle, dancing with none other than the future King Edward VII of England.

She had danced in 1860 at the Academy of Music with the Prince of Wales, who afterward became King Edward VII. That ball still lives in Manhattan’s social history. Hetty never ceased to boast of her personal triumph there.

Most young women were glad enough to be admitted to the function; a few thrilled at the thought of dancing just once with his highness, but Hetty determined to dance with him twice.

She described her costume as a simple white Swiss muslin dress with pink sash. On her feet were pink slippers, and in her ears were the golden balls of filigree work that she had worn at her debut. It was not her appearance, though, upon which she relied to accomplish her purpose….

Somewhere she had read that the prince was deeply interested in the spread of education among the common people of America. She pondered on this. When she was presented to the son of Queen Victoria the Prince of Wales heard with astonishment that he was meeting the Princess of Wales. The jest was explained to him by means of spelling. He laughed. Presently they were dancing.

Despite attracting the attention of royalty, the “Princess of Whales” never acquired a royal title. Rather, owing to her preference for black clothing and the unusual power she exercised as a woman financier she was called “The Witch of Wall Street.” In justice to Mrs. Green if she possessed occult abilities she was equally adept in white magic as well as black. For example, she bailed out the City of New York no fewer than three times which in the balance must be credited to her as a public good.

Hetty Green is very happy to do business with the financial officers of the city of New York, says the Times. At present the tax payers are indebted to “the wealthiest woman in America” in the sum of $1,500,000, advanced to meet city expenses. Hetty Green receives in return for her cash revenue bonds bearing interest at 3-1/2 per cent. Interest and premium are payable in October.

“Hetty Green is smart,” said an official of the department of finance yesterday. “During the summer months there is not much demand for money in Wall street. She loans New York city a million and a half, and just when the money market gets active in the fall the money comes back with good interest.

Hetty Green does not like to have her transactions with the city made public. A peculiar fact is that when Hetty Green goes to collect her money due on revenue bonds she can look up at the Stewart building and contemplate the fact that a mortgage for $1,000,000 on that structure also carries good interest.

We’ll leave readers with a few epigrams from Mrs. Green, and add that for brilliant success in research Readex offers many excellent resources, among them America’s Historical Newspapers.

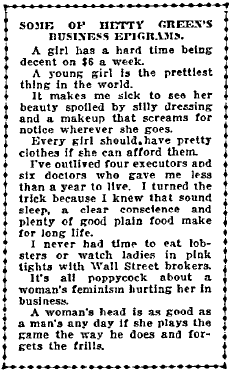

SOME OF HETTY GREEN’S BUSINESS EPIGRAMS

A girl has a hard time being decent on $6 a week.

A young girl is the prettiest thing in the world.

It makes me sick to see her beauty spoiled by silly dressing and a makeup that screams for notice wherever she goes.

Every girl should have pretty clothes if she can afford them.

I’ve outlived four executors and six doctors who gave me less than a year to live. I turned the trick because I knew that sound sleep, a clear conscience and plenty of good plain food make for long life.

I never had time to eat lobsters or watch ladies in pink tights with Wall Street brokers.

It’s all poppycock about a woman’s feminism hurting her in business.

A woman’s head is as good as a man’s any day if she plays the game the way he does and forgets the frills.

For more information about America’s Historical Newspapers, please contact Readex.