The Marginal Status of Marginalia: Some Thoughts

Most librarians must shudder at the thought of marginalia, since writing in books must be near the top of their taboo list. But many instances of marginalia have been hugely important (the scribblings of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Pierre de Fermat come to mind), and the other day I thought I might have tripped across some very interesting ones penned by Samuel Johnson. Granted, this was not the good Doctor himself, but the respected American philosopher who became the first president of King’s College (now Columbia University). Perusing Johnson’s Elementa Philosophica (1752) in Early American Imprints, Series 1: Evans, I noted the marginalia immediately, and also saw that it appeared to be signed by the author in the same hand. How very exciting! (The copy of this work that Readex digitized for this database came from the American Antiquarian Society, whose holdings contain many works donated by their authors, so this made sense.)

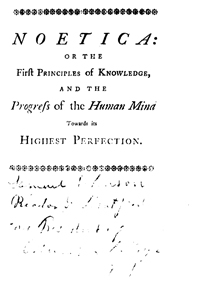

Here is what I was looking at:

And there was more! In several places in the text asterisks had been penned in and at bottom there were notes! An example:

Now, since the catalog records that are included in databases such as Early American Imprints (or in OCLC for that matter) do not contain copy-specific information about the cataloged work (those records are kept, generally, only by the institution that holds that copy), I didn’t look there for information about these marginalia. But when I did look at the full citation I saw that the notes field read: “Dedication to Lord Bishop of Cloyne signed by Samuel Johnson.” Ah hah!—but no: This note, of course, refers to the fact that the dedication is “signed” by Johnson in print on that page, not by hand. But that left the question: Were these Johnson’s own marginalia? If so, they certainly warranted a close look. Alas, the answer was short in coming, and negative despite all appearances. Below the “signature” the marginalia continues: “Rector of Stratford...President of Columbia College...” The problem was that King’s College wasn’t renamed Columbia until 1784 and Johnson died in 1772. Alas. In the end, I realized that most of the marginalia in the interior of this book were there because the book’s owner had simply followed the instructions on the Errata page and penciled in corrections directly in the text or margins. But this also got me thinking. There must surely be many instances where academic research libraries hold works that were donated to them by their authors. Such works might contain just the kind of illuminating annotations or edits that early authors were prone to pen, in an age when there were few alternatives for readily conveying them. In your own institution’s catalog records, the MARC 590 field contains the kind of copy-specific information that would include the identification (and possibly the attribution) of such marginalia. This is great for your own patrons, but remains invisible to outsiders. It occurs to me that the sharing of significant marginalia information might be accomplished by using the Crossroads tool that already exists in Early American Imprints. One could not only draw attention to any such marginalia in your holdings, but also put a link in Crossroads that would enable Imprints users to see relevant page images in PDF that you upload. What are your thoughts on bringing isolated marginalia into an organized access point?