Mission Impossible: America at War with Itself in its Indian Policy

Allowing that the American Civil War pitted North against South, it’s fair to characterize America’s un-civil war as that which the “Great Father” in the eastern seat of government waged against Native Americans in every corner of the union, but particularly in the west as it removed/exiled indigenous people consistently in that direction where they could be segregated and destroyed at leisure in the name of Manifest Destiny. Even for well-intentioned Indian agents, superintendents and commissioners, humanity often gave way to expediency, and honor fell prey to avarice and bureaucracy. Native American Tribal Histories, 1813-1880, provides comprehensive access to the written records of this tumultuous time.

Brigham Young, first Governor of Utah Territory and ex officio Superintendent of Indian Affairs for that territory famously opined that, in coming to terms with the Indians, “…even aside from the aspect of Christian duty, I am satisfied it will be cheaper to feed them, than to fight them.” The unspoken subtext of this statement is that the Indians were considered largely an economic problem, and that fighting them was never off the table.

Beyond pretensions to Christian charity, the United States government failed spectacularly in meeting its treaty obligations to feed the Indians, much less guaranteeing their security. When recognition of tribal sovereignty proved incompatible with the colonial project the government reverted to the Old Testament approach to resolving differences: total war. In the ruinous decades-long military campaign against America’s original people this country went to war with itself and its democratic ideals in no lesser degree than it did in the contest between the Blue and the Gray.

Governor Young’s sage advice was echoed by the agents and officials themselves, as for instance by Oregon Superintendent for Indian Affairs Absalom F. Hedges writing to his superior, George W. Manypenny regarding the dire conditions prevailing at Oregon’s Coast Reservation in January 1857 in the midst of a severe winter.

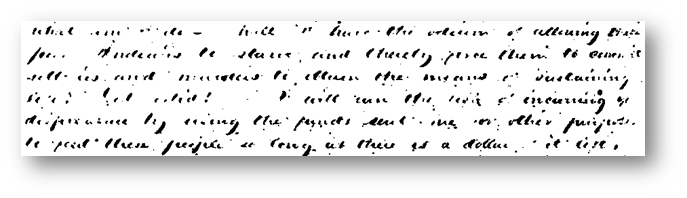

Shall I have the odium of allowing these poor Indians to starve and thereby force them to commit robberies and murders to obtain the means of sustaining life? God forbid! I will run the risk of incurring your displeasure by using the funds sent me for other purposes to feed these people so long as there is a dollar of it left.

Again, in February 1857, Hedges made the case that not honoring the treaties and the humanity of the Indians would lead to war:

I have so constantly urged upon your attention the fact that to desist from feeding these Indians is tantamount to a declaration of war with them, that I deem it unnecessary to say anything more in extenuation of the course I have adopted in this matter.

The vacillation of Indian policy between appeasement and annihilation was explicit in the conflict between Indian Agent Amos E. Rogers, in charge of Oregon’s Klamath Agency, and Col. C.S. Drew, in charge of keeping the peace in that fractious district. On August 1, 1863, while the Civil War was raging east of the Rocky Mountains, Rogers described the hostility he was encountering from Col. Drew in a letter to Oregon’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs, J.W. Perit Huntington. The spark for Drew’s diatribe excerpted below concerned the taking of clothes from a clothesline and possibly the theft of a horse from White settler John S. Love by an Indian known as “Klamath Joe.”

On the evening of our arrival at the big lake--immediately after the remark that he the next morning would tell the Indians to bring in the stolen horse &c., Col. Drew said! "When I get established here, I shall muster the Indians every day for roll call and make every one answer to his name! No Indian shall leave here either, without a pass from me. I shall plow up a piece of ground next spring, and by G-d they have got to put it in too--if it has to be done at the point of the bayonet! I will show Uncle Sam that there is a way to get along with Indians without having a set of whining Indian-sympathizing agents about to make promises to Indians never to be fulfilled.”

Despite his heated rhetoric, Col. Drew was only being honest about the government’s non-fulfillment of most of the promises it had made to Native Americans, from the fulsome commitments of the treaties right down to the shoddy quality of the annuity goods shipped to western agencies from eastern markets at costs many times greater than the value of the goods themselves. But Drew was just getting started:

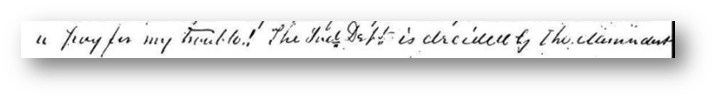

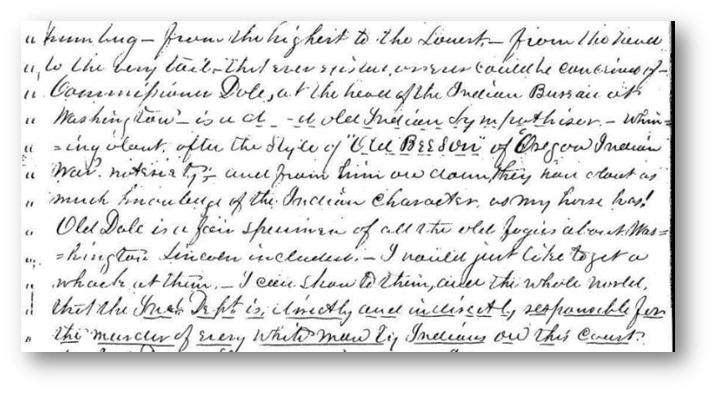

The Ind. Dept. is decidedly the damnedest humbug--from the highest to the lowest--from the head to the very tail--that ever existed, or ever could be conscious of--Commissioner Dole, at the head of the Indian Bureau at Washington--is a d----d old Indian sympathizer--whining about after the style of “Old Beeson” of ‘Oregon Indian war' notoriety--and from him on down they have about as much knowledge of the Indian character as my horse has! Old Dole is a fair specimen of all the old fogies about Washington, Lincoln included. I would just like to get a whack at them. I can show to them, and the whole world, that the Ind. Dept. is directly and indirectly responsible for the murder of every white man by Indians on this coast.

About those murders, well, there were quite a few. Readex’s term of art is “Indian and White depredations.” The trouble was that, in common with post-Civil War Reconstruction, America’s Indian policy was never consistently framed and implemented, or funded, or held to standards of justice that applied to other social institutions. As with the ostensibly emancipated slaves, the Indians were caught in an intractable situation. They didn’t even count as three-fifths of a person for political representation. They could neither vote nor own property. They were fair game for unscrupulous and racist citizens, and for a government more interested in selling land than in doing justice to sovereign nations.

For example, in Oregon Territory, the 1850 Donation Land Act prioritized a settler’s land claims without resolving Indian title to those lands in any way; conflict was guaranteed. Compensation to the Indians was deferred to aspirational treaties to extinguish Indian title. Emigrants trespassed on Indian lands and then laid legal claim to those same lands, sometimes benefiting from structures and improvements created by the Indians themselves. The below appears in J.W. Perit Huntington’s annual report for 1866 to Commissioner of Indian Affairs D.N. Cooley. More than a decade after the Donation Land Act the government was still playing fast and loose with Indian land.

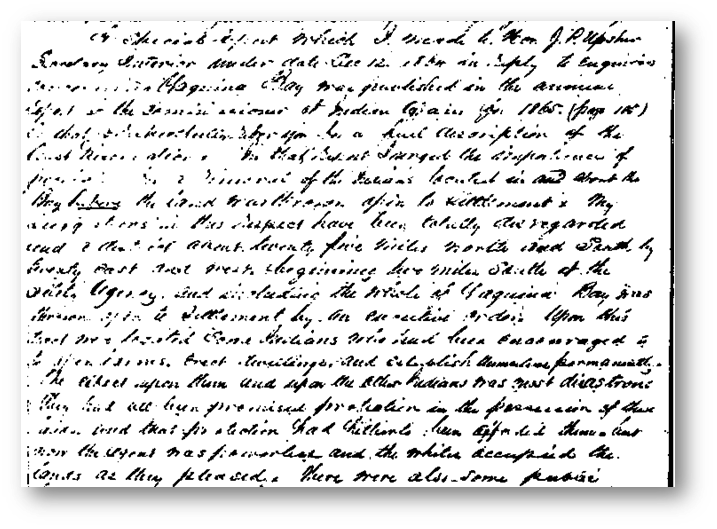

A special report which I made to Hon. J.P. [Usher], Secretary [of the] Interior under date Dec. 12, 1864, in reply to enquiries concerning Yaquina Bay, was published in the annual report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1865 (page 105). To that I respectfully refer you for a full description of the Coast Reservation. In that report I urged the importance of providing for the removal of the Indians located upon and about the bay before the land was thrown open to settlement. My suggestions in this respect have been totally disregarded, and a district of about twenty-five miles north and south by twenty east and west, beginning two miles south of the Siletz Agency and including the whole of Yaquina Bay, was thrown open to settlement by an executive order. Upon this tract were located some Indians who had been encouraged to open farms, erect dwellings and establish themselves permanently. The effect upon them and upon the other Indians was most disastrous. They had all been promised protection in the possession of these lands, and that protection had hitherto been afforded them, but now the agent was powerless, and the whites occupied the lands as they pleased.

Settlers routinely displaced tribes and bands, repurposed streams to mining operations, converted forests into lumber, and disrupted the lifeways and patterns of subsistence that held Native American culture together. The following appears in a letter from Huntington to Commissioner N.G. Taylor in 1867.

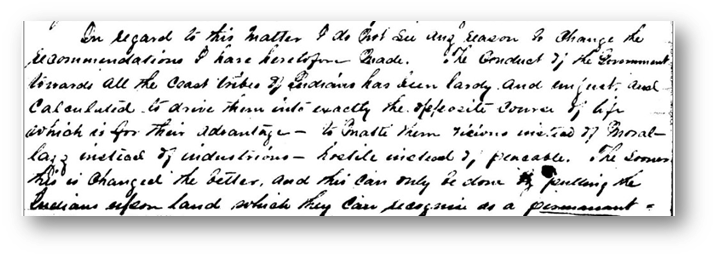

In regard to this matter I do not see any reason to change the recommendations I have heretofore made. The conduct of the government towards all the coast tribes of Indians has been tardy and unjust, and calculated to drive them into exactly the opposite course of life which is for their advantage--to make them vicious instead of moral--lazy instead of industrious--hostile instead of peaceable. The sooner this is changed the better, and this can only be done by putting the Indians upon land which they can recognize as a permanent home, the possession of which they may rely upon, and then encouraging them to cultivate the soil and abandon their fishing and hunting. The recommendations in my last annual report (1866) are what I would now urge in this regard.

2nd. Alsea Agency is in a very unsatisfactory condition. It should be abandoned and its Indians removed to Siletz or else more employees should be provided, tools and teams purchased and above all the assurance should be given that the possession of the lands shall be perpetual.

It is idle to expect an Indian to open a farm and erect dwellings &c. while in daily expectation of being dispossessed.

When the Indians objected to this existential threat, the emigrants called down the wrath of the U.S. Army upon their heads—unless a vigilante mob would better answer the purpose of “chastising” the Indians for defending their homes and families. An even more draconian response to Indian resistance was contemplated: turn over the Indian Department entirely to military authority. Here’s Oregon’s Superintendent Huntington discussing that subject with Washington Territory Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Thomas J. McKenny in 1867.

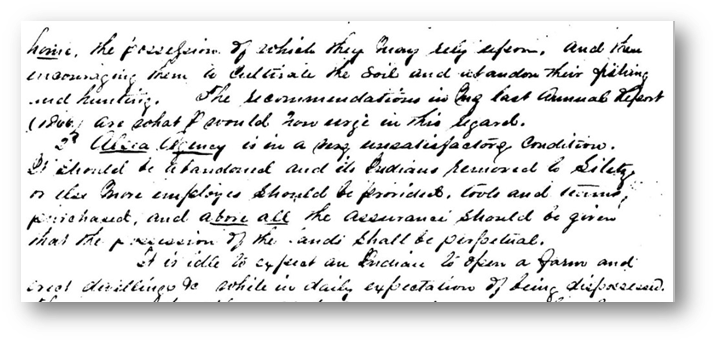

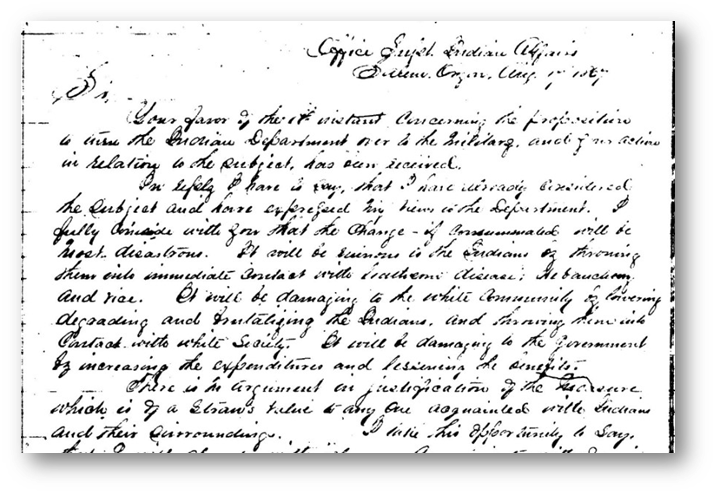

Your favor of the 6th instant concerning the proposition to turn the Indian Department over to the military and your actions in relation to the subject, has been received.

In reply I have to say, that I have already considered the subject and have expressed my views to the Department. I fully coincide with you that the change—if consummated—will be most disastrous. It will be ruinous to the Indians by throwing them into immediate contact with loathsome disease, debauchery and vice. It will be damaging to the white community by lowering, degrading and brutalizing the Indians, and throwing them into contact with white society. It will be damaging to the government by increasing the expenditures and lessening the benefits.

There is no argument in justification of the measure which is of a straw’s value to anyone acquainted with Indians and their surroundings.

As Col. Drew so vividly proposed, the federal government was perfectly willing to inflict slavery wholesale upon North America’s “Red” inhabitants “at the point of the bayonet” while fighting a war to liberate Black people from slavery. Under the guise of teaching the Indians farming methods they were held to servitude on reservations—plantations in the rough—often under brutal living conditions as Hedges noted above. If they did not produce, they starved. If they did produce, they were likely to be “removed” to some more desolate place as the settlers laid claim to the land they had improved.

In compliance with treaties, food, clothing, and tools were procured at Indian expense but through theft, misdirection, calamity and spoilage those items often never reached the tribes at all. When goods were delivered sometimes they were insufficient in quality or quantity, or wildly inappropriate for frontier life. At times the Indian agent caretakers of the reservations sold off annuity goods for personal profit. At times the agents traded things they needed for things they needed more. In many respects life on the reservations was as impossible for the agents as for the Indians themselves. The reader has heard of the proverb that begins, “For want of a nail…”? That was reality at Oregon’s Warm Springs Indian Agency in late October 1866:

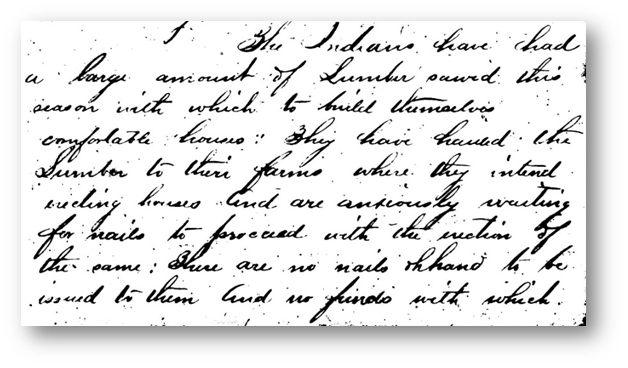

The Indians have had a large amount of lumber sawed this season with which to build themselves comfortable houses. They have hauled the lumber to their farms where they intend erecting houses and are anxiously waiting for nails to proceed with the erection of the same. There are no nails on hand to be issued to them and no funds with which to purchase. Nails for the purpose of erecting comfortable houses for the Indians and iron & oak lumber for repairing plows &c is at this time greatly needed.

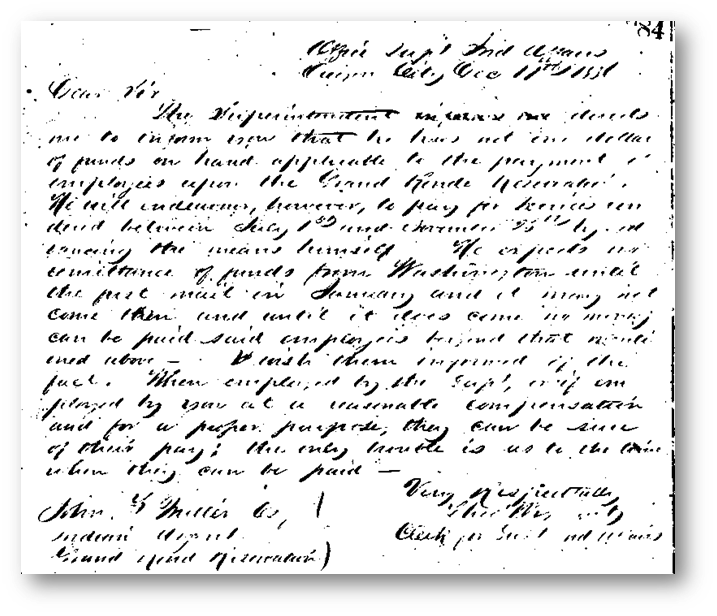

There would have been less cause for waste and malfeasance had the government been better at honoring its obligations to its sworn agents and officials in the first place. Salaries could take months to be paid, or the agents and employees might be forced to purchase the necessities of life at a premium because they lived far from banking centers and transportation points. Vouchers were substituted for cash, and getting those paid could take years. Agents were continually exhorted to exercise the utmost economy to the extent that they paid for vital supplies from their personal funds. Being an Indian agent was a logistical and financial nightmare. The following letter is addressed to John F. Miller, Indian Agent at Grand Ronde Agency, about halfway between Salem, Oregon and the Pacific coast.

The Superintendent directs me to inform you that he has not one dollar of funds on hand applicable to the payment of employees upon the Grand Ronde Reservation. He will endeavor, however, to pay for services incurred between July 1st and November 25th by advancing the means himself. He expects no remittance of funds from Washington until the first mail in January and it may not come then and until it does come no money can be paid said employees beyond that mentioned above. I wish them informed of the fact. When employed by the Dept., or if employed by you at a reasonable compensation and for a proper purpose, they can be sure of their pay; the only trouble is as to the time when they can be paid.

For such intransigence one might easily blame Congress itself as Indian treaties went unratified, budget appropriations were slow in coming or nonexistent, and the priorities of far-flung superintendencies and agencies were superseded by issues more accessible and relevant to Washington elites. Agents were subjected to a bewildering number of forms and reporting requirements. Many served apart from their families, and needed months of leave to attend to personal and business interests. It took a nearly heroic act of will for the agents not to abandon their charges entirely to the vagaries of fate. If they did cut their losses, their performance bonds could be forfeited, thus ruining them.

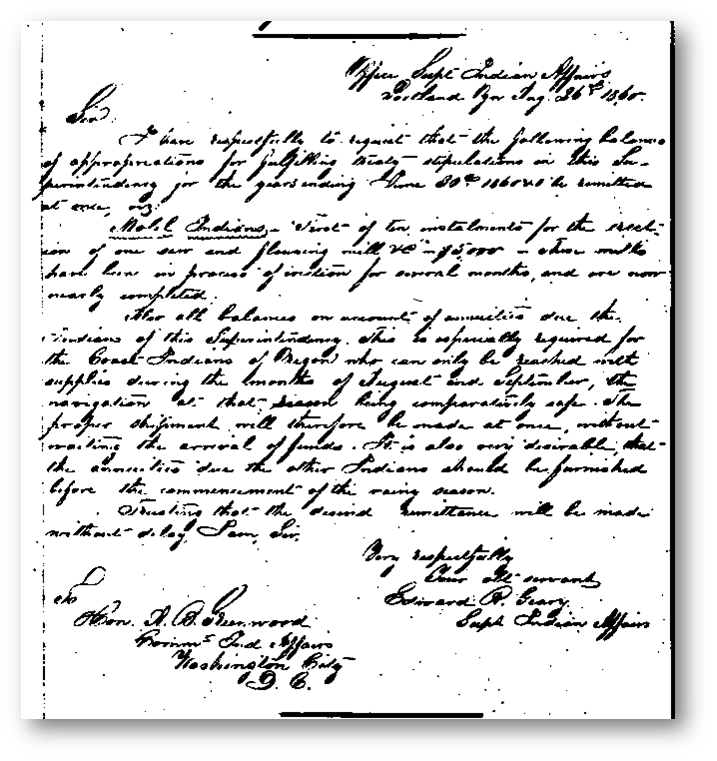

To insulate the Indians from White incursions on their lands, reservations were often sited in inaccessible places that were unsuited to sustained human habitation. Oregon’s Coast Reservation was so cut-off from trade routes and military support by weather and terrain that it could barely be supplied or protected for more than two months of the year. The following is from Oregon Superintendent Edward R. Geary to Commissioner A.B. Greenwood on August 26, 1860. He’s asking for funds and supplies—at the end of August. Do you think he’ll get them?

Molel [i.e., Molala] Indians—first of ten installments for the erection of one saw and flouring mill &c--$5,000—These mills have been in process of erection for several months, and are now nearly completed.

Also all balances on account of annuities due the Indians of this Superintendency. This is especially required for the Coast Indians of Oregon who can only be reached with supplies during the months of August and September, the navigation at that season being comparatively safe. The proper shipment will therefore be made at once, without waiting the arrival of funds. It is also very desirable that the annuities due the other Indians should be furnished before the commencement of the rainy season.

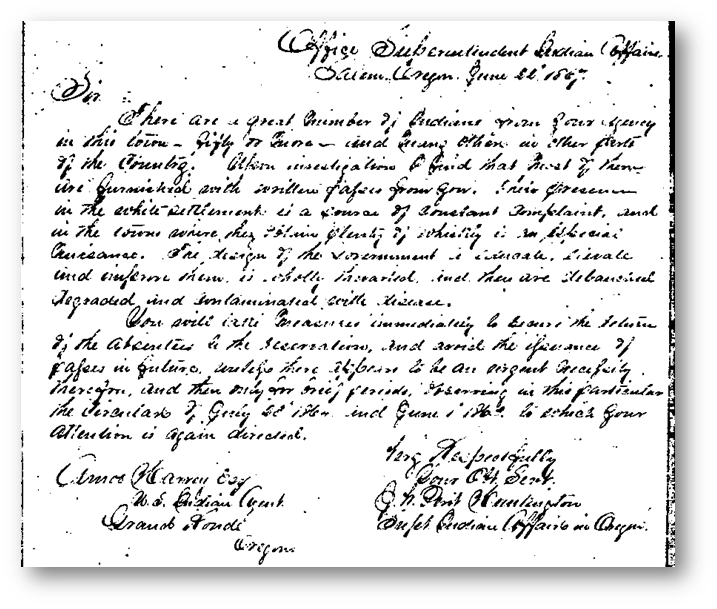

As Col. Drew suggested, passes were indeed required for Indians who desired to escape these benighted outposts. But if they left without permission, troops were dispatched to return them to penury and bondage. This letter was sent to Indian Agent Amos Harvey at Grand Ronde in 1867.

There are a great number of Indians from your agency in this town--fifty or more--and many others in other parts of the country. Upon investigation I find that most of them are furnished with written passes from you. Their presence in the white settlements is a source of constant complaint, and in the towns where they obtain plenty of whiskey is an especial nuisance. The design of the government to educate, elevate and improve them is wholly thwarted, and they are debauched, degraded and contaminated with disease.

You will take measures immediately to secure the return of the absentees to the reservation, and avoid the issuance of passes in future unless there appears to be an urgent necessity therefor, and then only for brief periods, observing in this particular the circulars of July 23rd 1864 and June 1st 1863, to which your attention is again directed.

Harassed by settlers, persecuted by troops, removed to ever more unproductive and remote regions ostensibly for their own good then dispossessed of their lands, many Indians chose to fight back which provoked increasingly severe measures from the military. There was the Cayuse War (1848-1855), the Snake War (1864-1868), the Rogue River Indian War (1853-1856), the Whitman Massacre (1847), and as many other named and unnamed skirmishes and outrages as any Civil War historian might cite for that conflict. But the Indians had no ironclad warships, no companies of artillery, and no diplomatic channels through which to plead their case. The Indian Department and its representatives should have provided for the latter contingency but as Col. Drew pointed out to the lasting shame of this country, it did not. The Freedmen’s Bureau was a paragon of humanity by comparison.

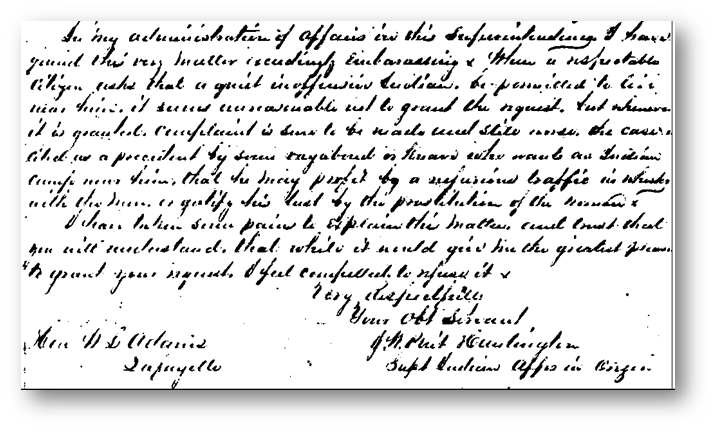

And then there was the cultural hegemony. Whiskey. Prostitution. Sanctimonious evangelists with feet of clay—or dogmatic intolerance for “heathen” ways. Children separated from parents. Interracial marriages torn asunder. Some Indians tried to get along only to be swindled and coopted by the settlers, and shunned by Indians who had already been down that path. Respectable behavior was no guarantee of equitable treatment by the government. Here’s Superintendent Huntington gracefully refusing the request of a settler that his Indian neighbor be allowed to continue living outside the reservation.

In my administration of affairs in this Superintendency I have found this very matter exceedingly embarrassing & when a respectable citizen asks that a quiet, inoffensive Indian be permitted to live near him it seems unreasonable not to grant the request, but whenever it is granted, complaint is sure to be made and still worse, the case is cited as a precedent by some vagabond or knave who wants an Indian camp near him, that he may profit by a nefarious traffic in whisky with the men, or gratify his lust by the prostitution of the women.

I have taken some pains to explain this matter, and trust that you will understand, that while it would give me the greatest pleasure to grant your request, I feel compelled to refuse it.

The glaring irony is that the “savage” Indians were exhorted to become “civilized” according to the White, colonial model, but were then ostracized by those same settlers after the Indians encountered the low-hanging fruits of civilization: alcoholism, social diseases, fungible morality, racially biased courts, and institutionalized violence as the most effective solution to every problem. It would be difficult to argue that the lot of the Indians was improved in the nineteenth century even by such innovations as repeating firearms, let alone by tribal recognition or conversion to Christianity.

The government enforced the Indians’ dependency, lied to them, gave their grievances short shrift, blamed them for their failings, then sought to wipe them out. One blushes to consider such an approach “policy,” in the same vein that it took until 1964 to redeem the promise of Black emancipation. And still we struggle to rise above prejudice. We must not forget it or gloss it over. These things happened, are happening still.

Visit the Readex Native American Studies page for information on this collection and more.