The Mound Builders: America’s Indigenous Engineers

There’s an entry in Readex’s Native American Indians, 1645-1819, from a book printed in Philadelphia in 1803 in which British topographical engineer Captain Thomas Hutchins described the “Kahokia tribe of Illinois Indians” as “having 50 houses and 300 inhabitants, possessing 80 Negroes.”

3. “Forty nine miles further northward of the Piorias’s village, and one mile from the Mississippi, on the southerly side of a small river,” he places the village Cahokia, so called “from the Cahokia tribe of Illinois Indians, having 50 houses and 300 inhabitants, possessing 80 Negroes.” The Kahokia tribe of Illinois Indians is small, and in his list of Indians, he places it near this village of their name.

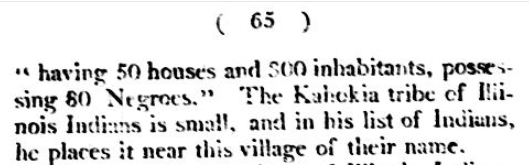

As shown at the northern end of Hutchins’ 1778 map, the Cahokia tribe lived a few miles east of present-day St. Louis, Missouri.

Contrast this modest village with the following illustration of “Cahokia” as it likely appeared ca. 1250 A.D. when its population was said to have rivalled London’s at that time. For it was then the commercial and ceremonial center of the Mississippian Indians and featured among other things a terraced earthen pyramid larger than any similar structure north of Mexico, with a more expansive base than the Pyramid of Cheops in Egypt. Like the Nile, the nearby Mississippi River provided Cahokians with rich soil in its floodplains and a ready means of transportation.

Cahokia

The largest ancient city north of Mexico, Cahokia was near present-day Collinsville, Ill. At its height between the 11th and 13th centuries, about 25,000 people lived there, as many as in contemporary London.

But how does a people who lived in expansive cities and built sophisticated structures, including “Woodhenge,” an astronomical calendar, and enormous effigy mounds resembling animals, vanish so completely and abruptly, leaving no reliable account of their existence? The rise and fall of the Mississippian Indians remains a mystery. No texts or oral history have survived their passing. Only their funerary barrows, artifacts and earthen structures remain as testimony to their use of geometry, their abilities as farmers and miners, their skill as artisans, and their religious practices.

So who were the Mississippian Indians? In the nineteenth century, opinions regarding their origins ranged from their being one of the twelve tribes of Israel to being Vikings, as seen in this 1897 article on “The Værings of America,” published in the Dallas Morning News:

The original colonists of Vinland and those who followed them in after years from northern Europe belonged to three different tribes or clans. In America, as in Scandinavia, the people of each tribe followed and obeyed every whim of their respective chiefs in war or peace, and as a consequence of dependence of the clansmen and independence of the chiefs, the several tribes or clans eventually separated, broke up their original colonial bond of union and became dispersed wanderers. Following their nomadic instincts, they wandered slowly away from the original region of mutual settlement in the east and thus separated, each clan originated a distinct mound system, along which, in the course of time thriving and populous agricultural communities were established under the guardianship of a member of the hereditary ruling family of the race.

In 1887 Professor F.W. Putnam, curator of the Peabody Museum at Harvard College, speculated that the Mississippian Indians were the descendants of “four great antique races” that intermingled in the vicinity of Cahokia. His lecture on the topic was described in the Portland Morning Oregonian:

The four great races can be resolved into two—the long headed people and the people with short and broad heads. There is evidence that the long headed people came from northern Asia, and, crossing Behring strait, continued their way downward as far as California. Then they crossed to the great lakes, went down the St. Lawrence, made their way along the Atlantic coast as far south as North Carolina, and spread themselves into Ohio and Pennsylvania. There is evidence that they resembled the people of northern Asia in face and form.

The short headed people had the characteristics of the people of southern Asia, and resembled the Malay race. The first traces of them we find in Peru and Central America. From there they worked toward the north into Mexico, New Mexico, Arizona, and following the rivers which empty into the gulf of Mexico, notably the Mississippi, they mingled at last with the long headed people in Tennessee and Ohio, and were finally absorbed by them. The Indian is a descendant of those two races.

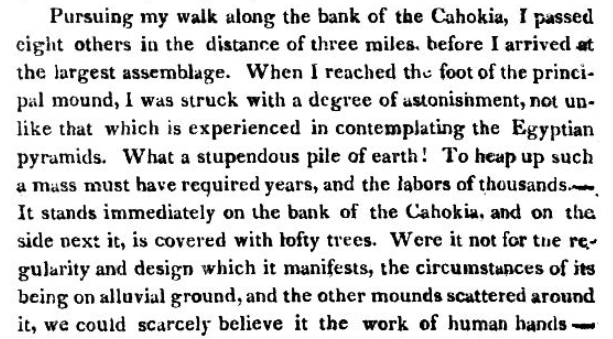

In 1811 journalist, diplomat and member of the American Antiquarian Society Henry Marie Brackenridge described Monk’s Mound, the most prominent manmade feature of the region where the races purportedly met, in the following words:

Pursuing my walk along the bank of the Cahokia, I passed eight others [i.e., mounds] in the distance of three miles before I arrived at the largest assemblage. When I reached the foot of the principal mound, I was struck with a degree of astonishment, not unlike that which is experienced in contemplating the Egyptian pyramids. What a stupendous pile of earth! To heap up such a mass must have required years, and the labors of thousands….It stands immediately on the bank of the Cahokia, and on the side next it, is covered with lofty trees. Were it not for the regularity and design which it manifests, the circumstances of its being on alluvial ground, and the other mounds scattered around it, we could scarcely believe it the work of human hands.

Ah, but what lay beneath these mounds? Excavations sponsored by the University of Illinois and undertaken in 1922 by pioneering archaeologist Warren K. Moorehead gave us a glimpse into the lives of the mounds’ creators, as reported by the Kalamazoo Gazette:

FINDS 52 SKELETONS

During five weeks of work just completed, Dr. Moorehead unearthed three cemeteries, 52 skeletons, 23 funeral jars and urns, countless small art objects and implements of peace and war, and, most important, an altar; six mounds were penetrated. The altar was in the center of the base of one of the mounds. The mound has a diameter of about 160 feet and was about 24 feet high. The altar is a basin-like structure of baked clay, about 18 inches in diameter, its sides being three inches thick. It was filled with ashes—the nature of which has not been determined.

A similar altar was found during the preliminary work last fall and others have been unearthed in other mounds in other sections of the country. It is the theory of Dr. Moorehead that the mound builders used these altars in connection with ceremonial rites. They were inserted, as this one was, in a large platform of fire-baked clay, evidently a dance floor, and when their ceremonial usefulness was ended, they were covered with earth—hence the mounds.

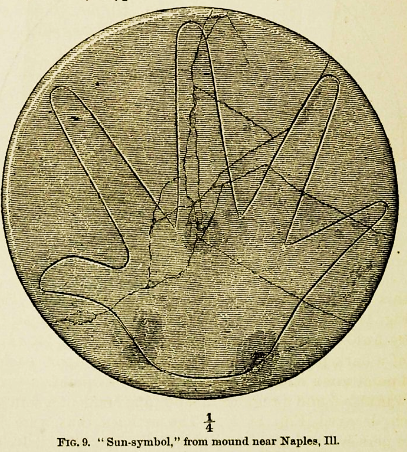

Mississippian earthen structures weren’t limited to regular geometric forms; they were also expressed as animals. For example, a snake:

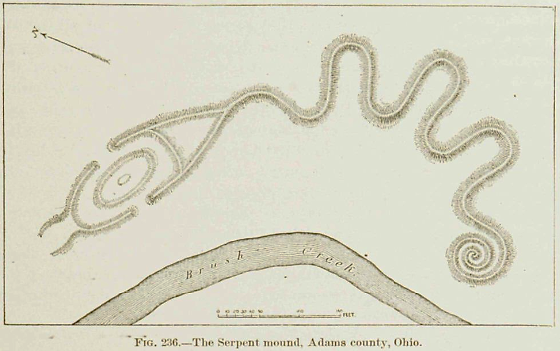

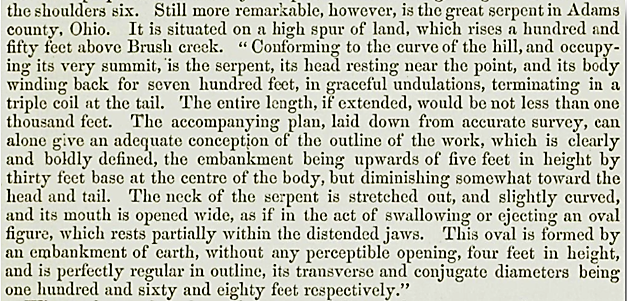

The above illustration and the excerpt below come to us from several annual reports of the Smithsonian Institution, for the years 1890-91 and 1862, respectively. The drawing is by W.H. Holmes in 1888. The excerpt is from Professor John Lubbock’s review of fieldwork by archaeologists E.G. Squire, E.H. Davis, and I.A. Lapham relating to earthen structures in the Mississippi Valley.

Still more remarkable, however, is the great serpent in Adams county, Ohio. It is situated on a high spur of land, which rises a hundred and fifty feet above Brush creek. “Conforming to the curve of the hill, and occupying its very summit, is the serpent, its head resting near the point, and its body winding back for seven hundred feet, in graceful undulations, terminating in a triple coil at the tail. The entire length, if extended, would be not less than one thousand feet. The accompanying plan, laid down from accurate survey, can alone give an adequate conception of the outline of the work, which is clearly and boldly defined, the embankment being upwards of five feet in height by thirty feet base at the centre of the body, but diminishing somewhat toward the head and tail. The neck of the serpent is stretched out, and slightly curved, and its mouth is opened wide, as if in the act of swallowing or ejecting an oval figure, which rests partially within the distended jaws. This oval is formed by an embankment of earth, without any perceptible opening, four feet in height, and is perfectly regular in outline, its transverse and conjugate diameters being one hundred and sixty and eighty feet respectively.”

Cahokia and similar sites throughout North America remind us that early Native American culture was more varied and sophisticated than that of the relatively small tribes of hunter-gatherers encountered by European colonists.

Since the Pyramid of Cheops cited at the outset is considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, it’s fitting that the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has recognized the Cahokia Mounds as a world heritage site. Although the Mississippian sites themselves have suffered greatly through the ravages of time, their legacy lives on in Readex’s Archive of Americana.

To learn more about any of the Readex products used to research "The Mound Builders: America's Indigenous Engineers," please contact Readex.