Native Removal Prior to the Indian Removal Act of 1830: Highlights from Native American Tribal Histories

This is the first in a series of blog articles highlighting primary source content from the Readex Native American Tribal Histories collection. The articles in this series offer further insight and added perspectives into westward expansion, the Trail of Tears, the history of Manifest Destiny, and the impacts to Native Americans.

"To be driven off from the house of our ancestors, leave here the bones of our wives and children…”

In the history of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1830-1850 is often referred to as “The Removal Era,” named for the Indian Removal Act signed May 28, 1830. The Indian Removal Act promised lands west of the Mississippi River to Native Americans in exchange for their lands within territory claimed by the United States. But the policy of removal did not emerge from nothing. For several years before 1830, many government officials and settlers pushed for the removal of Native Americans from their homes by any means necessary.

In April 1824, a petition to William Clark, Superintendent of St. Louis, from residents of Fulton County stated:

That the inhabitants of this county have have [sic] for a long time been so been so [sic] much oppressed by the various Tribes of Indians living on the Military Lands and its vicinity (Particularly on the farmers) that we think it encumbent [sic] upon us for the safety of ourselves and familys [sic] and protection and welfare of our property to petition the general government through you as a public agent for a removal of said indians [sic] from our vicinity…[i]

Another petition from Florida in 1826 echoed the same frustrations:

...the Indians located in Florida near Alachua, are roaming at large over the country, doing serious mischief to the Inhabitants by killing their cattle & hogs, robbing their plantations, and enticing away their slaves.[ii]

The petitioners stated, "Your Memorialists further state that without an adequate force, they will never be able to recover their property. The Governor has told your Memorialists, that he has frequently applied to the Government for power to call out the military to scour the Swamps in the Indian boundary, and to recover their runaway slaves, and that as yet, no such power has been given to him…and threatened “reprisals on the Indians which may end in a war of extermination”[iii] if their enslaved property was not returned and the Native Americans brought to heel.

Officials and settlers generally agreed Native Americans and whites could not live together, and many pushed for Native removal to “their own lands,”[iv] conveniently forgetting Native Americans were there first. In 1826, Joseph M. White, an official in the Florida Territory, wrote to James Barbour:

Sir, under any system, whether dictated by the unavoidable requisitions of a coercive policy, or emanating from the milder suggestions of persuasion, there are invincible obstacles to continuing the Indians in Florida. Amalgamation with the white Inhabitants were in vain, under the difficulties arising from opposition of character; the measure of concentrating them is also attended with difficulties, as past experience has shown; and if persevered in, the Indian lands would continue to be the haunts of runaway slaves, and be resorted to by smugglers and fugitives from civil authority.[v]

In March 1826, in a letter to James Barbour, then Secretary of War, William Clark outlined an extensive plan “for the preservation and civilization of the Indian tribes … to save them from extinction.”[vi]

Joseph M. White was less politic in his support for removal, and wrote in January 1826, “Florida would be relieved from a disease, which has preyed upon its inhabitants with a morbid severity, and the General Government would at the same time be exempted from the embarassments [sic] inseparable from reiterated complaint.”[vii]. Clark proposed:

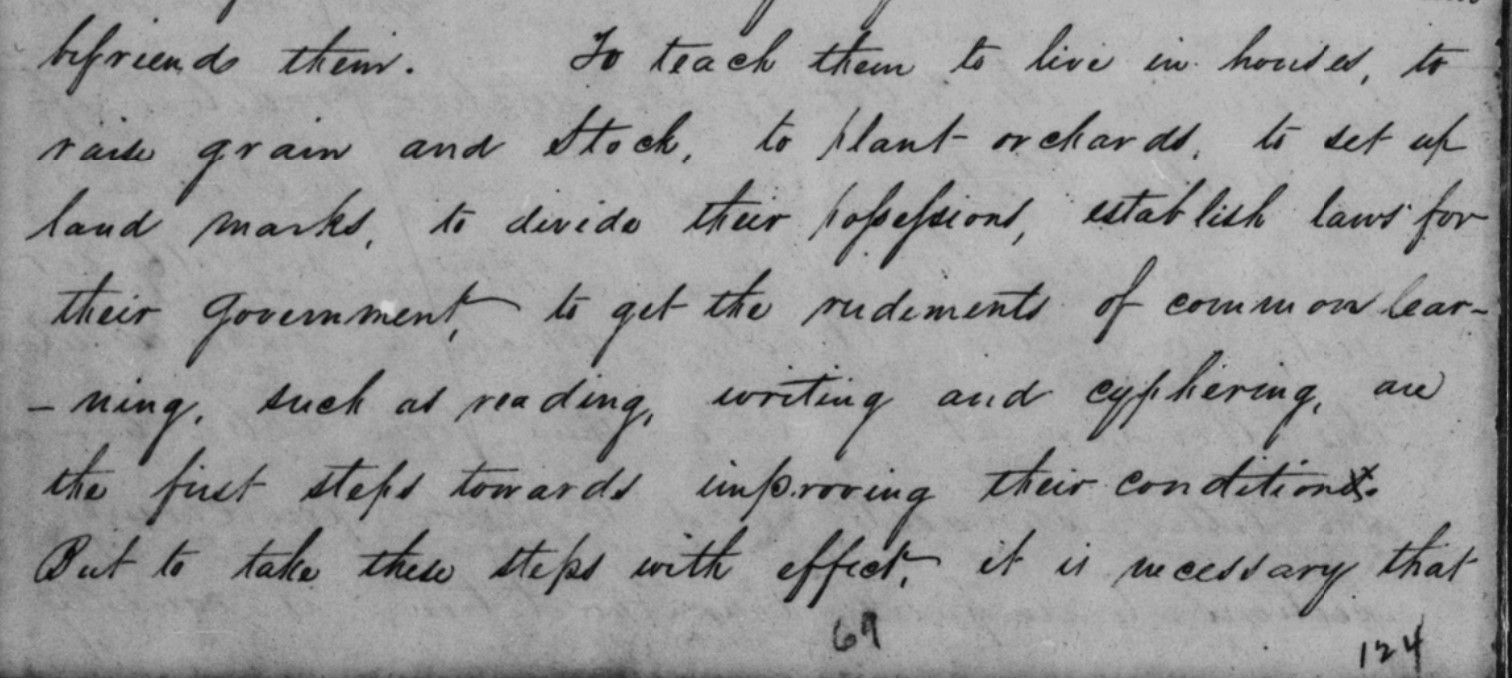

To teach them to live in houses, to raise grains and stock, to plant orchards, to set up land marks, to divide their possessions, establish laws for their government, to get the rudiments of common learning, such as reading, writing, and cyphering, as the first steps towards improving their conditions. But to take these steps with effect … the tribes now within the limits of the States and Territories should be removed to a Country beyond those limits, where they could rest in peace, and enjoy in reality the perpetuity of the lands on which their buildings and Improvements would be made.[viii]

Clark believed this segregation and “civilization” project would effect “the commencement of a new era of prosperity in the condition of a people, who have strong claims upon the Justice and Generosity of this Government.”[ix] The “Country beyond” suggested by Clark was the land west of the Mississippi River and Missouri. This plan was not without its complications; many Native groups resisted removal, while the federal government seriously underfunded the removal process.

Many Native groups were – unsurprisingly – unwilling to move from their ancestral homes. In December 1827, Potawatomi leader Senachwine wrote to William Clark,

Brother, the news that you bring wounds our hearts and makes us look back to the days our Fore Fathers. To move from the land that gives us food is hard; but to be driven off from the house of our ancestors, leave here the bones of our wives and children at this inclement season of the year, is calculated to break our hearts.”[x]

Peoria chief Wapachicanan protested the removal of his people in 1828, saying,

Father, we never sold, nor given, our land. Yet we are deprived of them, and we know not why. We claim it as our property, and can not get them. Father, you have become the possessor of the County when the bones of our Fathers are scattered. You have build large houses with our stones, and the clay that covered the bones of our ancestors, and your Friend & children the Peoria are poor and helpless.[xi]

The Peoria had been forced to cede much of their land following the Treaty of Edwardsville in 1818 and were now faced with the prospect of removal.

Following Clark’s playbook, many agents stressed “the conviction of the truth that it is impossible for them to remain as independent nations within the limits of these States & Territories.”[xii] While Clark maintained a positive attitude about the removal process, agents and other local officials wrote more plainly about the task they undertook. In a letter to the Secretary of War in October 1824, William P. Duval wrote “to purswade [sic] and threaten them into a peaceable removal from this truly delightful country, required the exercise of uncommon patience, time, and prudence.”[xiii]

In November 1825, Thomas L. McKenney wrote similarly about the resistance he encountered; “But from the dissatisfaction which these Indians have expressed from the commencement of their removal, and their horror of the Country allotted to them, and its acknowledged barrenness and insalubrity, it is not reasonable to expect that there will be any change in their dispositions…”[xiv]

In a letter to John Quincy Adams, dated December 14, 1827, the Chiefs of the Shawnee wrote:

We call upon you to fulfill your promise to us, you promised all your Red Children, that would move from among the Whites, a piece of Land, where we might live and our Wives and Children should never be disturbed, and that the Land should always be our own, this is the Land we want to go to, do that and you will make us all happy.”[xv]

They continued:

We cannot move to the Lands, you wish to give us without assistance, we are poor, and we have to travel through White settlements, and they will not give us any thing to eat, without paying for it, and when we pass them, there is not game enough to support us; now we want you to take pity on us, and send some person to go with us, and when we are in want, to furnish us with provisions.[xvi]

Other Native American tribes were coerced to move from their lands by economic deprivation or threats of force. In January 1825, William Clark wrote to the Secretary of War,

Every exertion has been made to remove those bands & unite them with the Tribes West of Mississippi without effect as yet. Believing that the aid of the Legislature of that state would facilitate the accomplishment of that object; I have addressed a letter to the Governor of Illinois suggesting the propriety of the Legislature of that state prohibiting the Trade with those bands after the 1st of June next under heavy penalties until licensed by the Superintendent or Agent, and also prohibit their planting corn within the states, on lands not their own. Those measures if adopted will most probably inforce [sic] their removal.[xvii]

Trade with Native groups was heavily regulated, and their land use strictly enforced. By cutting off these avenues of survival and resistance, Clark hoped to remove their ability to stay in their homes. If those measures failed, violent force was threatened.

In November 1827, Richard Graham threatened the Kickapoo;

… for the last time, that you must all move early in the spring to your own lands… Take this caution & do not run your wives & children into any distress with the White people. It has been only your Great Father’s arm that has restrained the White people from driving you off before now, he will not hold it back any longer, he says you must go, he will not listen any longer to your Talk, asking him to let you stay another year.[xviii]

Those groups who were persuaded to move west of the Mississippi River encountered significant difficulties along the way. In his original plan, Clark proposed to “facilitate their removal by placing agents at suitable points where they will cross the Mississippi, and at other points on the line of March, to supply them with provision, ammunition, &c.,”[xix] but in practice these agents were often meagerly supplied.

In a letter dated April 4, 1827, local Indian Agent Richard Graham wrote from the banks of the Mississippi River:

… I beg leave to report that I found in two separate encampments 203 Shawnees & 24 Senecas emigrating from the State of Ohio to the West of the Mississippi: they appear to be in a miserable condition having parted with nearly all their wearing apparel to supply themselves with provisions on their journey. It appears they left their villages in Ohio in Nov. & arrived at the present encampment in Feby. since when they have been furnished with a scanty supply of Corn, they have not been able to proceed on to their place of destination, owing to the extreme leanness of their horses, many of which have died for the want of means to purchase grain for them … they expect with the aid of Corn, to be able to resume their journey in May.[xx]

Graham wrote on to recommend:

… that instead of the scanty supply which they now get, they should receive per each Individual a ration, to consist of 9 oz of salt meat, or 1 lb of fresh meat, & 1 lb of Flour, or Indian meal per day & 4 lbs salt for every hundred rations, and One Gal. of Corn per day for each horse.[xxi]

In an appeal to the Secretary of War for more funding in October 1827, William Clark wrote:

…no part of the appropriation made at the last session of Congress has been considered applicable to this object [removal], the payments have been made from the funds placed in my hands to carry into effect the provisions of the late Treaties with the Osage, Kansas & Shawanees [sic], which will be required in the Course of the present year.”[xxiii]

Little money was forthcoming, and Clark wrote again in January 1828:

“You inform me that it has become necessary, from the limitted [sic] amount provided for the contingencies of the Indian Department, that it can no longer bear the encreased [sic] demands upon it for the cost of Emigration. The reply to which, I beg leave to observe, that in consequence of the encouragement given to the Indians by the General Government to remove west of the Mississippi, several Tribes relying on the generosity and humanity of the Government, determined to move in Bands, or parties. Divers of those parties have come on, … it is to be hoped that Congress will make a Special appropriation for this object; otherwise many of those who have not as yet the means of supplying themselves, will unquestionably starve, or be compelled to kill the Cattle & hogs of the Whites; which is already beginning to produce excitement in many parts of these frontier states.”[xxiv]

He further appealed to the federal government, and asked:

“Will Congress compell [sic] me to say to that unfortunate people ‘you have told me that you came to this side of the Mississippi, and left your own abundant fields and comfortable homes, under assurances that you were to receive land for yourselves & your children for ever; and to be assisted until you could raises cows & provisions for your support; but no appropriation has been made for those objects; no assistance can be afforded you; you must go to the country assigned you west of Missouri, and do the best you can; you shall not hunt within, or near our settlements.’ The feelings of those wretched people, on receiving such language from the Agent of a Government which they may have considered just and humane, may more easily be imagined than described.”[xxv]

In August 1828, William Clark wrote that:

As the wild game diminishes, the pressing calls of those unfortunate people upon the humanity of the Government for assistance encreases [sic]. Several Small parties have moved from the east of the Mississippi, which I am not only compelled to assist in moving on, but furnish them with provisions, which from the limited appropriations of funds for that object, those emigrating Indians are necessarily conferred to the Scanty allowance of one peck of Corn per week [around two dry gallons], and 1/4 of a pound of meat per day each, with a little salt and occasionally a little flour.[xxii]

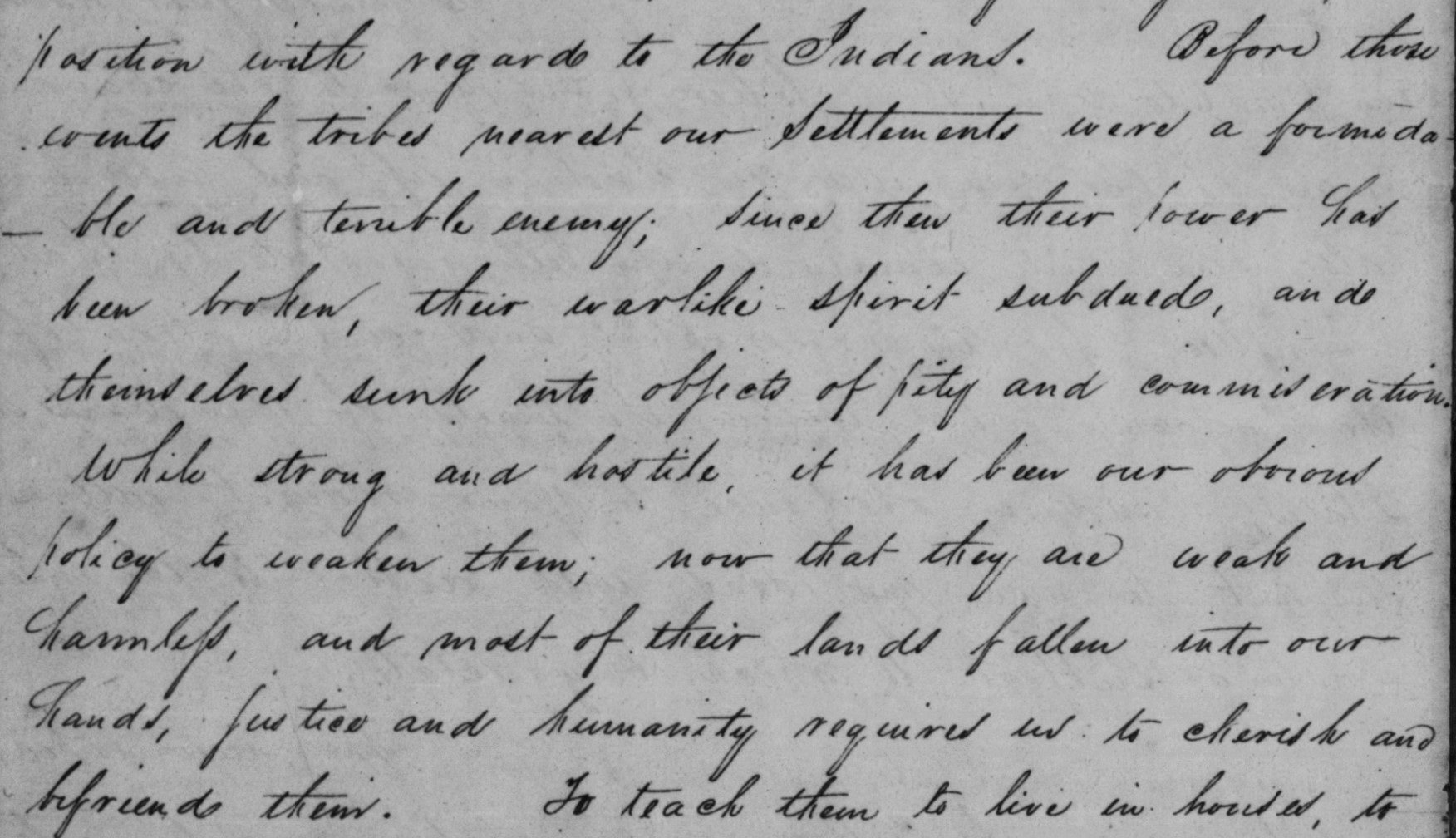

While Clark petitioned for more funding, governmental neglect of and hostility to Native needs was standard policy. Indeed, in his March 1826 proposal for removal, Clark acknowledged:

Before those counts the tribes nearest our Settlements were a formidable and terrible enemy… While strong and hostile, it has been our obvious policy to weaken them…[xxvi]

Although the Indian Removal Act would not be signed until 1830, the effort to move Native American nations en masse was already well underway by the end of the 1820s. Removal was accompanied by repeated treaty-making, which nibbled away at Native lands and rights, and which will be examined in this series’ next installment.

[i] [Petition from Residents of Fulton County to William Clark, April 6. 1824]

[ii] [Letter from Joseph M. White to James Barbour, April 28, 1826]

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] [Petition from Residents of Fulton County to William Clark, April 6. 1824], [Letter from William P. Duval to John Caldwell Calhoun, July 29, 1824], [Letter from Ninian Edwards to William Clark, June 12, 1828]

[v] [Letter from Joseph M. White to James Barbour, Jan. 31, 1826]

[vi] [Letter from William Clark to James Barbour, March 1, 1826]

[vii] [Letter from Joseph M. White to James Barbour, Jan. 31, 1826]

[viii] [Letter from William Clark to James Barbour, March 1, 1826].

[ix] Ibid.

[x] [Letter from Senachwine to William Clark, Dec. 14, 1827]

[xi] [Letter from Wapichacanan to John Quincy Adams, July 22, 1828]

[xii] [Letter from William Clark to James Barbour, March 1, 1826]

[xiii] [Letter from William P. Duval to John Caldwell Calhoun, Oct. 26, 1824]

[xiv] [Letter from Thomas L. McKenney to James Barbour, Nov. 28, 1825]

[xv] [Letter from Shawnee Chiefs to John Quincy Adams, Dec. 14,1827]

[xvi] [Letter from Shawnee Chiefs to John Quincy Adams, Dec. 14,1827]

[xvii] [Letter from William Clark to John. C. Calhoun, Jan. 22, 1825]

[xviii] [Letter from Richard Graham to the Kickapoos, Nov. 23, 1827]

[xix] [Letter from William Clark to James Barbour, March 1, 1826]

[xx] [Letter from Richard Graham to Unidentified Recipient, April 4, 1827]

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] [Letter William Clark to Peter B. Porter, Aug. 1, 1828]

[xxiii] [Letter from William Clark to James Barbour, Oct. 20, 1827]

[xxiv] [Letter from William Clark to Thomas L. McKenney, Jan. 20, 1828]

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] [Letter from William Clark to James Barbour, March 1, 1826]

Visit the Readex Native American Tribal Histories page for information on this collection and to request a complimentary trial.