Politics and Prophylaxis: The World Health Organization, the Politics of International Public Health, and Open Source Epidemiology

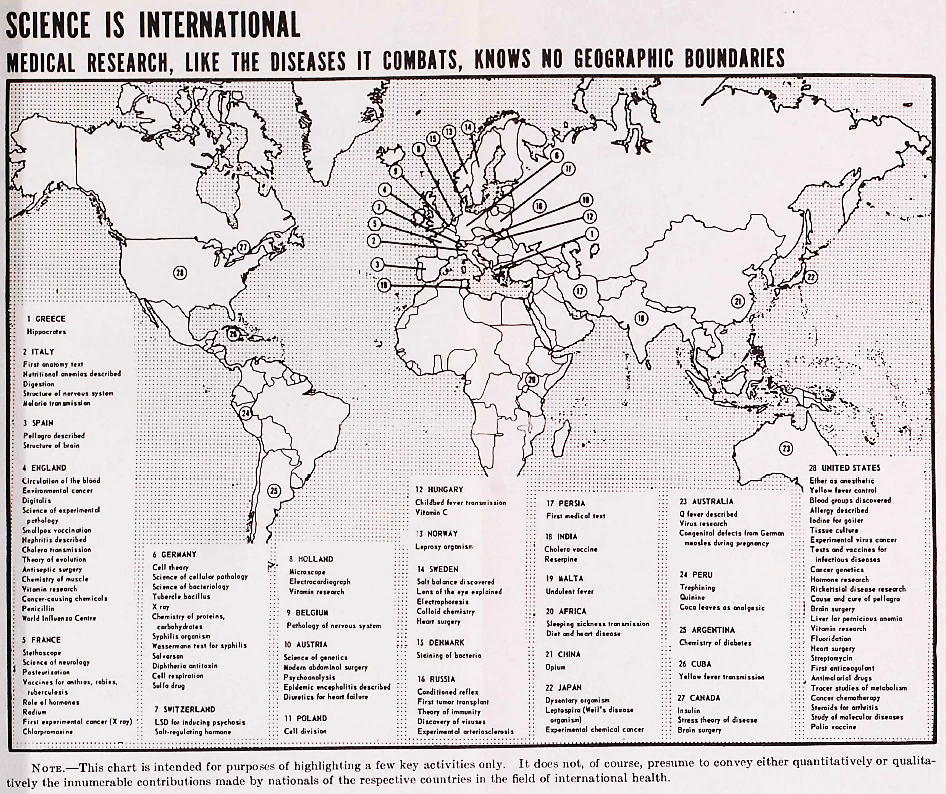

In June 1958, about eight months after the Soviet Union’s Sputnik satellite circled the globe, former Illinois governor and future United Nations ambassador Adlai Stevenson had an idea for another scientific endeavor with global implications: What if the world community could cooperate on achieving a selection of public health goals that knew no boundaries?

U.S. Senate majority leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas had Stevenson’s speech printed in the Congressional Record. Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota promoted Stevenson’s idea on the world stage culminating in its adoption by the UN’s World Health Organization (WHO) in 1959. It would subsequently be sponsored by the UN as the International Health and Medical Research Year (abbreviated as IHY), and coincide with the WHO’s Twelfth World Health Assembly in 1961.

What is IHY? It is a proposed International Health Year to be sponsored by the World Health Organization of the United Nations.

If the plan for it goes through it will be put into effect in June, 1961. During the following year all the nations of the world would contribute their skill and knowledge in an all-out war against cancer, heart disease, mental illness, old age and infants’ diseases, as well as many other human ills.

The International Health Year was modeled on the International Geophysical Year (IGY) that called for the coordination of scientific investigations from July 1957 through December 1958. Collaboration on research in Antarctica was one of the notable accomplishments of the IGY. The launches of the first Soviet and American satellites also occurred during the IGY, which its advocates hoped would ease Cold War tensions.

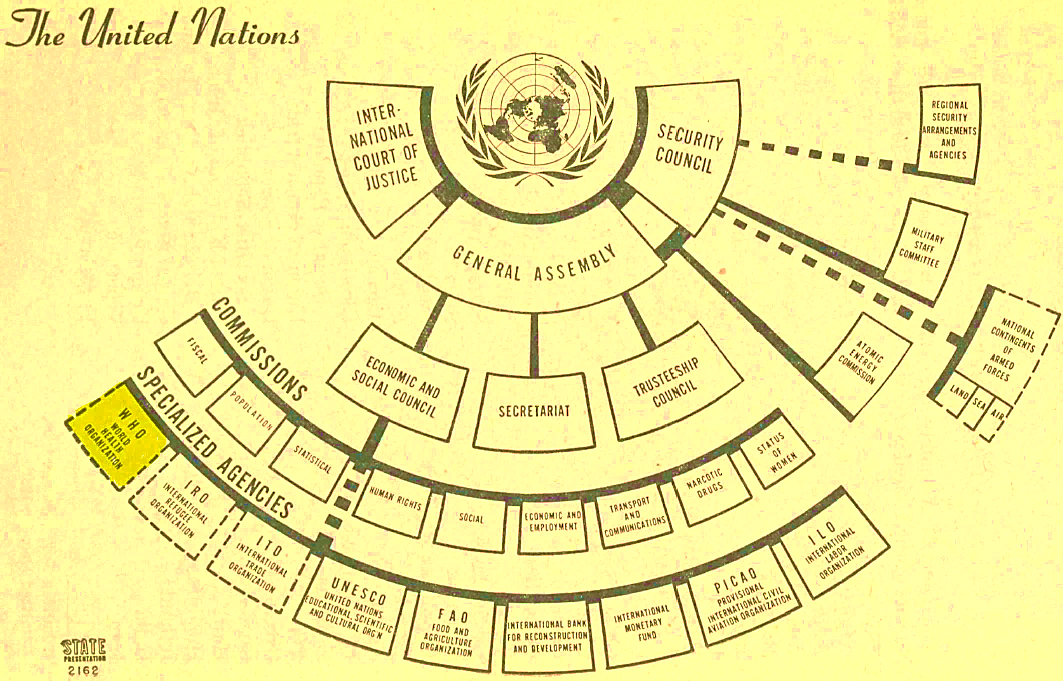

The WHO was created in large part to address public health crises resulting from World War II. Its predecessor, the League of Nations’ Health Organization, was created in 1920 for similar reasons following World War I. The WHO constitution was adopted in July 1946 during the UN’s International Health Conference in New York City and entered into force on April 7, 1948, “World Health Day.” Today the WHO is a member of the United Nations Sustainable Development Group, a consortium of international agencies focused on social and economic development.

WHO initiatives are broadly social and apolitical although they are often created in response to political issues. For example, Senator Humphrey proposed that the 1961 IHY focus on problems relating to radioactive fallout. Understandably, nations engaged in atmospheric nuclear testing were disinclined to share their data and minimized the impact of their own activities. Senator Humphrey sought to reframe the discussion in global rather than national terms.

The atom hangs over mankind like the very cloud it precipitates. Past and present U.S., British and Soviet testing of atomic and hydrogen weapons has resulted in drenching the atmosphere with trillions of radioactive fragments. We have recently learned the alarming fact that this deadly debris is falling out of the atmosphere much faster than the public had been informed, and is most concentrated in the northern United States.

A war over fallout

How significant is this fallout to human health? This is the topic of bitter controversy throughout the scientific world. Charge and counter-charge fill the air. The squabble adds up to one fact: No one is really sure about the effects of fallout.

IHY can strengthen the efforts of all the scientific agencies studying the problem by pooling their findings, so that needless fear or groundless complacency can be avoided and sensible counteraction taken.

The controversy regarding radioactive fallout reemerged following the Chernobyl nuclear accident in Ukrainian SSR on April 26, 1986. Several weeks after that momentous event health experts gathered at the World Health Organization to reassure nervous Europeans and call for international coordination of the response.

Eleven health experts from European nations including the Soviet Union have urged a coordinated international reaction after any future nuclear accident, by way of immediate information exchanges. At a meeting here on the aftermath of the April 26 Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the Ukraine, they also decided its “acute stage” had now passed, and new protection measures against ionising radiation were no longer needed. Their recommended future response would include surveillance, with immediate data exchanges at both international and even national level.

“We have encountered communication problems in different services, even in Western countries,” World Health Organisation deputy director Dr. J.P. Jardel said after the experts had discussed the Chernobyl aftermath here Tuesday. While regretting a lack of information from countries like the Soviet Union, the experts recommended lifting post-Chernobyl measures like travel and food import restrictions, introduced by some countries for want of full facts. But they said nuclear fall-out from clouds over Europe could create long-term regional problems in places including northern Sweden, Bavaria in southern West Germany, and Poland.

Global authority can also lead to more stringent measures as was shown by a subsequent post from Agence France-Presse in which the WHO was cited as providing the benchmark for radioactive contamination that was exceeded by spinach grown in the Alsace region of France.

Consumption of spinach from the eastern French region of Alsace was on Tuesday banned by Industry Minister Alain Madelin after tests showed a level of radioactivity above international norms. The spinach registered 2,600 becquerels a kilo (2.2 lbs), 600 more than that permitted under norms fixed by the World Health Organisation. The spinach can still be frozen or canned since its radioactivity should disappear completely in ten weeks and drop to under 2,000 becquerels at the end of the week.

Mr. Madelin said on radio on Tuesday that the measure was just a precaution. “One would need to eat two tonnes of this spinach in a few weeks to reach the point at which medical supervision could be required,” he said.

Alsace was reportedly one of the regions of France most affected by the radioactive cloud from the disabled Chernobyl nuclear plant in the Ukraine.

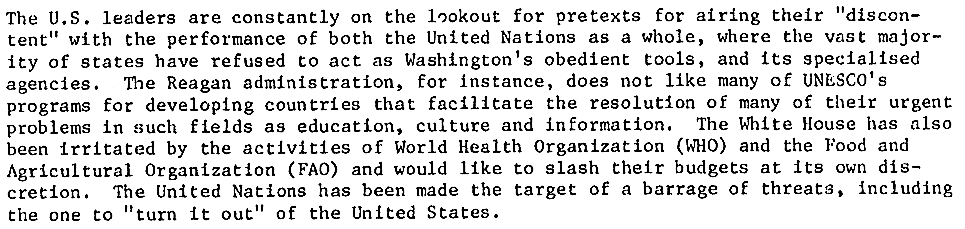

East-West tensions were evident in 1983 when the Soviet Union accused the United States of trying to control the UN by cutting its financial support for the organization. The WHO was noted as a target of U.S. parsimony:

The U.S. leaders are constantly on the lookout for pretexts for airing their “discontent” with the performance of both the United Nations as a whole, where the vast majority of states have refused to act as Washington’s obedient tools, and its specialised agencies. The Reagan administration, for instance, does not like many of UNESCO’s programs for developing countries that facilitate the resolution of many of their urgent problems in such fields as education, culture and information. The White House has also been irritated by the activities of World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and would like to slash their budgets at its own discretion. The United Nations has been made the target of a barrage of threats, including the one to “turn it out” of the United States.

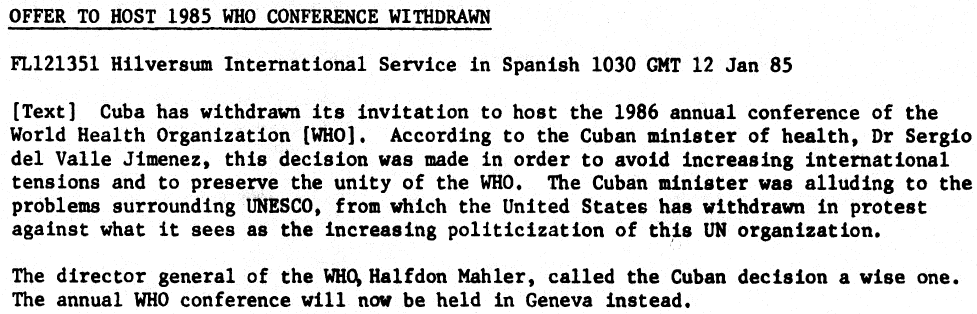

Another East-West twist occurred in 1985 when the U.S. took the political step of withdrawing from UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) to protest the politicization of that body. This indirect threat led Cuba to withdraw its bid to host the 1986 WHO annual conference.

Cuba has withdrawn its invitation to host the 1986 annual conference of the World Health Organization [WHO]. According to the Cuban minister of health, Dr Sergio del Valle Jimenez, this decision was made in order to avoid increasing international tensions and to preserve the unity of the WHO. The Cuban minister was alluding to the problems surrounding UNESCO, from which the United States has withdrawn in protest against what it sees as the increasing politicization of this UN organization.

The director general of the WHO, Halfdon Mahler, called the Cuban decision a wise one. The annual WHO conference will now be held in Geneva instead.

Zionism and outright colonialism continues to be a challenge for the WHO. The occupied Palestinian territory (its official UN designation) currently has non-member observer status although its sovereignty is recognized by the majority of member states excepting the United States, Israel, and other nations that favor direct Palestinian-Israeli negotiations. The WHO was not above criticizing Israel in an official resolution in 1976 as it sought to raise the profile of the health needs of the Palestinians distinct from their national aspirations.

The 29th World Health Assembly, now under way here, has condemned Israel for its actions which undermine the health of the Arab population on the territories, occupied by Israeli troops.

The resolution says that the policy of deportation and mass arrests of Arabs, destruction of Arab villages and establishment of Israeli settlements in their place, which is carried out by Israel on these territories, adversely affects the physical and mental condition of the Arabs on the occupied territories.

The WHO’s work hasn’t always been bureaucratic or contentious, however. The same organization that has championed modern scientific methods to solve complex problems was able to embrace Chinese traditional medicine.

About 2,000 doctors from all over the world come to China every year to study its unique traditional medicine and acupuncture and modern medical results.

For the dissemination of the Chinese medicine, the World Health Organization has set up seven cooperative centers in China. Acupuncture is being practised in well over 120 countries now.

In this medical exchange, China—two thirds of its medical achievements in the last few years are near or have reached advanced international levels—has established ties with over 100 countries and regions.

The WHO could also be critical of China. In a 1988 article that echoes present-day concerns over government transparency during epidemics, China committed to being more forthcoming with health information following an epidemic of hepatitis A.

China has promised to release information promptly on communicable diseases following repeated requests by its neighbors.

The pledge was made yesterday at a regional public health conference in Shenzhen organised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) for Hong Kong, China and Macao.

Health officials from Beijing and Guangdong will sign an agreement today with Hong Kong and Macao officials guaranteeing regular meetings and exchanges of information on the outbreak of communicable disease.

Hong Kong’s Director of Medical and Health, Dr Thong Kah-liang, who led a delegation to the three-day meeting in Shenzhen, described the results as very satisfactory.

“I’ve got everything I wanted. Everybody in the meeting agreed to provide information on a regular basis. It is a major move in improving co-operation in the region,” he said.

China was earlier criticised by the director of WHO Disease Prevention and Control Regional Office for the Western Pacific for not volunteering details on the spread of epidemics in the country.

Thousands of people in Shanghai have been infected by the hepatitis A virus and there has been concern that the epidemic could spread.

A WHO representative in Beijing, Dr Goon Hean Tat, said China had previously been slow to inform the world of epidemics because official information was released only by the Central Government in Beijing.

In the selections above it’s evident that Readex’s Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) Daily Reports, 1941-1996, includes a multitude of historical perspectives with contemporary relevance. A related collection, Joint Publications Research Service (JPRS) Reports, 1957-1995, offers open source English-language translations of foreign print media spanning a similar timeframe and also vetted by the U.S. government.

One of Readex’s JPRS topical databases, Morality and Science: Global Origins of Modern Bioethics, 1957-1995, includes the 1968 Russian monograph, Results of Half a Century of Combatting Infections in the USSR and Certain Urgent Problems of Modern Epidemiology. In the introduction author P.N. Burgasov makes the case for a historical understanding of epidemics:

Our duty is to describe objectively the fifty years of soviet public health service in its difficult struggle against epidemics.

This has to be done because it is impossible to train future communist physicians without knowing well the historical past of our country. They must know what a high price was paid in achieving the present control of epidemics. The same has to be done with respect to biology which has played an important role in searching for the most effective means of preventing infectious diseases. It is impossible to understand the processes occurring in modern natural sciences, particularly in biology, or to attempt making predictions regarding the development of science in the future, if we do not analyze thoroughly the road covered in this direction.

Would you like to go a little further back in the history of epidemiology? JPRS includes the two-volume Plague Bibliography. Russian Literature, 1740-1964, Parts I & II, published in 1968.

This bibliography of the literature dealing with the plague includes the most diverse sources: monographs and original works, theses, abstracts, newspaper articles, special government decrees, laws and ukazes. In addition to works published in the Russian language, it includes articles by Russian authors in the foreign press.

The 1918 influenza epidemic is often cited as offering valuable insights as we struggle with the COVID-19 pandemic. Readex collections also allow us to learn from the East Germans as they dealt with an influenza epidemic from 1968-1970:

Summary

An attempt to describe the migration of influenza on the basis of a weekly notification of all acute feverish infections of the respiratory tract, taken kreis by kreis, proved the usefulness of this method for epidemiological analysis. The correlation by period and area of the influenza epidemics occurring in the GDR from 1968-1970 with influenza epidemic migration beyond the national border is discussed.

Another monograph in Morality and Science: Global Origins of Modern Bioethics, 1957-1995, consists of selected chapters from O.V. Baroyan’s 1971 Evolution of 'Conventional Diseases'. Much of the work relates to the epidemiology of biological weapons but its content is nonetheless relevant to pandemics caused by natural rather than manmade pathogens. In the following excerpt from page eleven, Baroyan is talking explicitly to us in 2020:

Actually, how will the question of “conventional diseases” stand in the year 2000 and later, in the beginning of the 21st Century? Is there any scientific substantiation for believing that by the beginning of the next century, mankind will be entirely liberated from the threatening and serious epidemics of the past? May not the world again encounter the plague of the Middle Ages or a new, seventh pandemic of cholera? Might epidemics of exanthematous fever or yellow fever again arise? What will be the status of smallpox, etc.?

Chapter VI of Baroyan’s book begins with a quotation from Volume 27 of the Fourth Edition of Vladimir Lenin’s Works:

A simple all-text search for “Baroyan” in Morality and Science: Global Origins of Modern Bioethics, 1957-1995, yields 81 results including all of the JPRS works cited above.

Robust research results lead to progress which bears more than a passing resemblance to prophecy. Readex offers both the content and the analytical tools to allow history to inform scientific hypotheses to solve real-world challenges in epidemiology and health policy.

To see what students and scholars at your institution can discover with Readex products, contact Readex today.