“R and R from Racism” at Idlewild—Michigan’s African American Resort

The evocative quotation in the title comes from Dr. Benjamin Wilson, professor of history at Western Michigan University, who in 2002 wrote Black Eden: The Idlewild Community.

“R and R from racism” was the way Benjamin Wilson put it. Wilson, who holds a doctorate in history, is an associate professor in black Americana studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. He has done considerable research on Idlewild’s storied past.

It was a refuge from bigotry, he said.

“You couldn’t go to Las Vegas,” Wilson said. “The only way you could get in was if you went in the back door dressed as a waiter.”

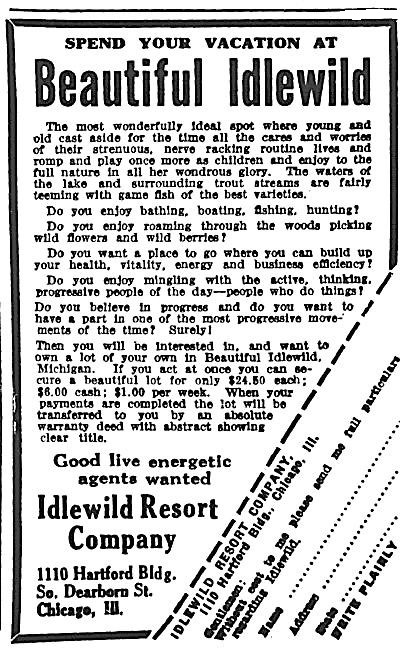

Idlewild was the preeminent African American resort town from the 1920s until the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. Its ascent began in 1912 when four real estate investors bought 2,700 acres of timberland in Yates Township, Michigan, about 75 miles north of Grand Rapids and 35 miles east of Lake Michigan. The sandy soil in the area was unsuitable for farming; however, a number of small lakes showed promise for beaches and waterfront development.

The developers offered for sale on installment 25-foot x 100-foot lots for $24.50 each: six dollars down and a dollar per week. Their target demographic was the newly emerging Black middle class who would go on to build seasonal cabins in Idlewild. Prominent people such as heart surgeon Daniel Hale Williams, author W.E.B. Du Bois and entrepreneur Madame C.J. Walker also purchased land there for more substantial dwellings. They supported the provision of utilities to the area and put Idlewild on the African American cultural map.

Idlewild was close enough to large Midwestern cities to draw a wide range of Black vacationers, and far enough out of the way to allow them to leave segregated society behind. It became a combination of summer camp, Chautauqua society and red-hot nightspot, a place where for a few weeks each summer misgivings about race could give way to “R and R”—rest and relaxation with “active, thinking, progressive people.”

Just a dozen years after its founding Idlewild was marketed in the Cleveland Plain Dealer as “the greatest resort in the world” for African Americans.

As evidence that the optimism expressed in the ads above wasn’t unfounded, that same year a special train carrying vacationers to Idlewild was noted when it passed through Grand Rapids en route to Baldwin, just west of Idlewild.

A special train will pass through the city Sunday bringing an excursion party of about 500 Negroes going to Idlewild, the resort near Baldwin, which they have established.

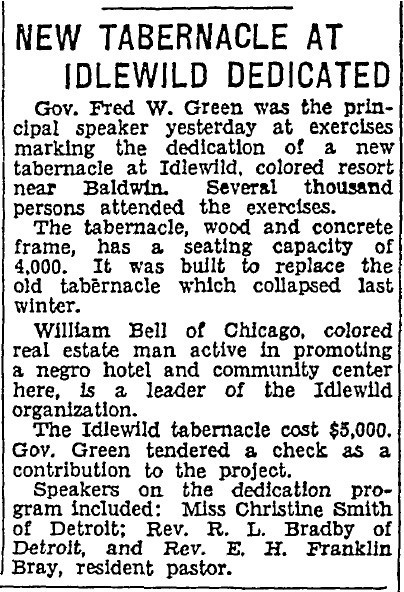

A few years later Michigan Governor Fred W. Green spoke at the dedication ceremony for a 4,000-seat, $5,000 tabernacle in Idlewild. It would be one of nine churches eventually built there.

Gov. Fred W. Green was the principal speaker yesterday at exercises marking the dedication of a new tabernacle at Idlewild, colored resort near Baldwin. Several thousand people attended the exercises.

The tabernacle, wood and concrete frame, has a seating capacity of 4,000. It was built to replace the old tabernacle which collapsed last winter.

William Bell of Chicago, colored real estate man active in promoting a negro hotel and community center here, is a leader of the Idlewild organization.

The Idlewild tabernacle cost $5,000. Gov. Green tendered a check as a contribution to the project.

Speakers on the dedication program included: Miss Christine Smith of Detroit; Rev. R.L. Bradby of Detroit, and Rev. E.H. Franklin Bray, resident pastor.

Despite its rural location, Idlewild’s social and cultural opportunities were compared favorably with large cities. In 1927 Chicago’s Light and Heebie Jeebies newspaper described it as a summer retreat where “the social bars are let down.” Paradise Lake is in Idlewild, so the area was actually mentioned twice.

Summer is the informal season when everybody meets everybody. It is well known that lampshade makers as well as society leaders like to get away, for a few days, a week, just get away somewhere. And often enough the folk of all classes meet—at Idlewild, maybe at Riverwood, maybe at Paradise Lake, Atlantic City, New York, Cleveland or Detroit. Somehow or other, when the classes get away from home they merge and mix a little. The social bars are let down. At Idlewild there will be found persons treating one another cordially who lift their skirts high when they pass in Chicago.

In the mid-twentieth century, due to restrictions on African Americans owning property and enjoying services comparable to those to which Whites had access, a secondary economy and social network developed specifically to meet the needs of Black citizens. Idlewild carried such authority as a haven from racial strife that the Idlewild Chamber of Commerce was noted in the Chicago Bee as endorsing the famous Negro Motorist Green Book in 1946.

After four years absence, The Negro Motorist Green Book, the official guide to hotels, tourist homes, restaurants and other places where Negroes are welcomed without embarrassment, will be in circulation once again. It will be [off] the press next month and will list some 3,500 places throughout the country, all the leading Negro newspapers, schools and colleges and information about the new cars.

The Green Book is used by all the Automobile Clubs of the United States, the United States Travel Bureau and endorsed by the Idlewild Chamber of Commerce.

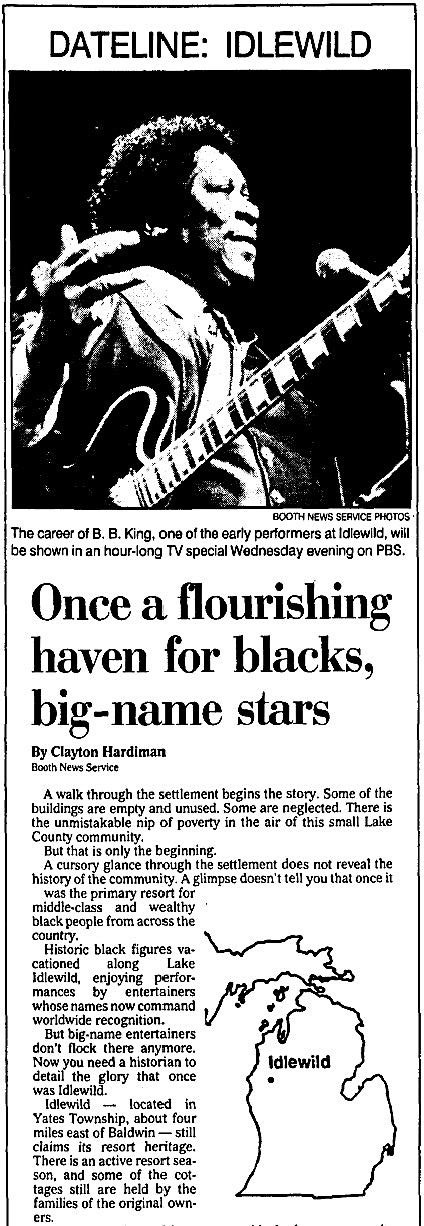

Idlewild attracted Black-owned businesses that offered all of the amenities associated with high-end resorts. Certainly the entertainment offerings at Idlewild justified comparisons to urban landmarks such as Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom and Apollo Theater. Distinguished performers such as the Count Basie Orchestra, Duke Ellington, Della Reese, Sarah Vaughn, James Brown, The Four Tops, Aretha Franklin, and B.B. King included Idlewild on their tour of what was called “the Chitlin’ Circuit.”

In 1975 a writer in the Detroit News reminisced about Idlewild’s Paradise Club as the “Summer Apollo” prior to the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act:

It’s been just about a dozen years ago, but it seems like a century, for many have been the changes wrought in that time. It was a time when black entertainers weren’t welcomed in most of the big clubs across America, and certainly before black customers’ money was negotiable at most “white” establishments.

From that injustice the Paradise Club was born. Situated in Idlewild, about 200 miles from Detroit in Lake County over in west-central Michigan, the Paradise Club was America’s best-known black summer resort.

The Paradise Club was known throughout the black entertainment world as the “Summer Apollo,” the resort version of the star-studded shows at Harlem’s Apollo Theater.

It was a place where black performers and black audiences got to stretch out. It was at the Paradise Club that you might see Dinah Washington, Roy Hamilton, Al Hibbler, Sam Cooke or any of the other major black acts of the time.

Two of Idlewild’s larger venues, the Flamingo Bar and the Paradise Club, offered two shows nightly with staggered hours so patrons could go from one club to the other. The arrangement emulated the Savoy Ballroom’s “two bandstand” model with a pristine beach thrown in for good measure. Parties and after-parties became the stuff of legend.

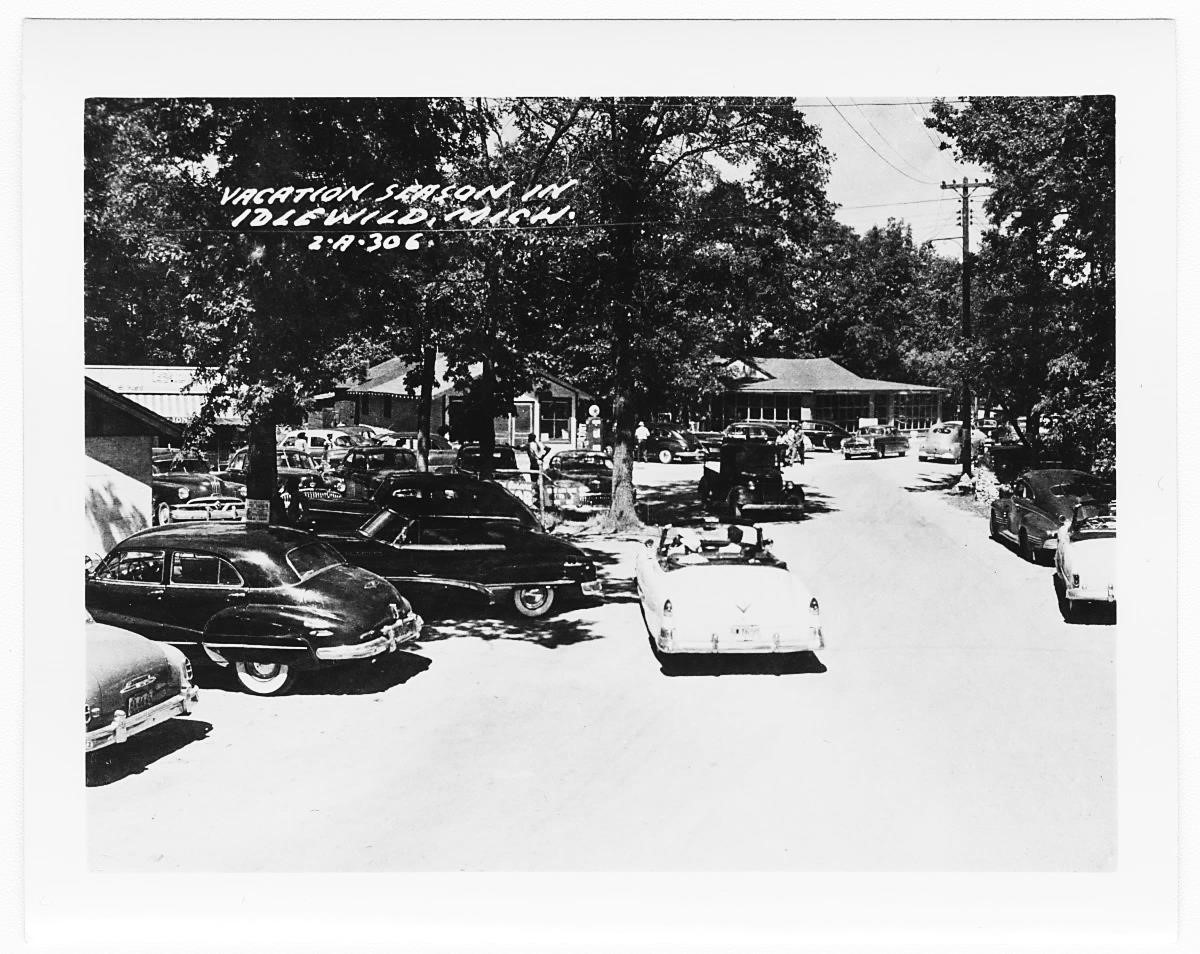

At its height in the 1950s and early 1960s, Idlewild boasted nightclubs, supper clubs, an amusement park, and an assortment of hotels and rustic cabins nestled around small, spring-fed lakes. Approximately 25,000 people visited each year to indulge in hunting and fishing, horseback riding, roller skating, tennis, billiards and watersports.

In the 1964, the year during which the long-awaited Civil Rights Act passed, 89-year-old Idlewild founder Charles Gess sought to reverse the resort’s imminent decline by soliciting new board members.

Gess and two other persons, Mrs. Lena [i.e., Lela] Wilson of Idlewild and Ray Trucks of Baldwin, now comprise the board. All are original members. “We’re not going to live forever,” Gess said.

The board numbered 10 or more a few years ago when the area was at its height with an estimated 2,000 summer residents and many thousands more weekenders who fished and hunted and enjoyed name entertainment at public and private clubs in the area.

Gess, who thought up the name Idlewild and who helped organize the first land sales, said the area was the only resort area in the United States where Negroes had exclusive say in its operation. The idea was revolutionary at the time.

But interest began to lag a year or two ago when more and more other recreation and resort areas became integrated. Last summer was particularly dull with not a single name band or singer in one of the clubs.

John Bankston, editor of the Grand Rapids Times, a Negro newspaper, said he found the beach at Paradise Lake deserted one hot July afternoon, an unheard of situation in former years.

Thus Idlewild’s fortunes waned as new opportunities elsewhere opened up for African Americans. Today there’s a museum and cultural center celebrating Idlewild’s notable past, a small year-round population, and plenty of affordable real estate in the former “Black Eden.”

For more information on Black Life in America, Series 1 and 2, please contact Readex.