Researching the Chinese Cultural Revolution Using FBIS Reports: A Personal View of the Impact of Digitization, 1990 to 2013

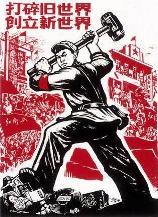

It was January 1990, and I looked out my dorm window at the snow falling, yet again. Forecasters were calling for nine more inches, adding to the foot already on the ground. Winter in upstate New York can be brutal, and the thought of trudging across campus to the library to research my Modern History thesis wasn't appealing. But following a recent class discussion about why so many Germans blindly followed Hitler's insane directives, I wanted to explore why so many Chinese citizens blindly followed the Red Guards and Mao Zedong during the infamous Chinese Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1978. In 1990, China was still reeling from the horrors of the Tiananmen Square massacre the year before, and I wanted to understand these questions, “How did Mao build such a cult of personality and incite mass imprisonment, torture and public humiliation of its citizens, and was China headed back towards a new kind of revolution?“

As I fired up my Mac Plus, DJ Casey Kasem announced on the radio Sinead O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” as the number one song on "American Top 40." After the modem’s distinctive, yet irritating whirring and beeping noises stopped, my computer finally connected to the college’s fledgling intranet. Once on the library’s new OPAC, I saw that the university had several print editions and some miscellaneous microfiche of my go-to resource, the reports on the People’s Republic of China created by the Foreign Broadcast Information Service.

To this day, the FBIS Daily Report remains an incredibly valuable resource for modern historical research. Consisting of English translations of local radio and TV broadcasts, speeches and newspaper stories from over 100 countries from 1941 to 1996, the FBIS Daily Report was distributed daily to U.S. government organizations that needed to know what was being broadcast and reported around the world in other countries’ media. The archive expanded daily, and today we have a five-decade-long record of historical events as they occurred and were reported in-country. I thought that by reading Mao’s proclamations and speeches, and understanding how the state-controlled Chinese media spun stories, I could better understand how a nation of 700 million (at the time) could so blindly follow a man’s directive toward anarchy.

I bundled up in my 1987 Descente Ski Parka and trudged across the quad to the library. Shaking off the snow, I walked over to the z39.50 client terminal to find more detail on where I could find the FBIS Daily Report and other sources for information on Mao’s policies and Chinese media. If lucky, there might be a citation pointing to stories on CD-ROM. But no. Aside from abstracts in ABI/Inform, I was going to have to research this the normal way—in print and fiche.

It took 25 minutes, but I finally found the four printed FBIS Daily Reports on China that were available. My library had the China Report from April 13, 1975, May 29, 1976, December 4, 1977, and June 11, 1984. I started reading each from cover to cover, looking for any reference to Mao. The April 13, 1975, report included a translation of a newspaper story about Mao having visited a farm collective to encourage the farmers to increase production. The May 29, 1976, report had several stories about Mao’s meeting with visiting Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. (This meeting, incidentally, would be Mao’s last public appearance before his death less than four months later). Fishing out a handful of dimes, I put sixty cents into the photocopier to print the relevant articles.

Although I found the reports fascinating—they gave glimpses of daily life in China during a period notoriously closed to the West—three hours had passed and I hardly had begun to gather the primary research needed to write an entire thesis. It was time to break out the big research guns.

Most of the library’s microfilm and microfiche were kept in the library basement—a location I avoided if at all possible. It was always cold, the dust gave me a runny nose, and it smelled like rotting cabbage. The library had only recently acquired CD-ROM technology, and now with three terminals located near the main entrance, most students quickly turned to CD towers for their research. The library basement was quickly becoming a lonely and forbidding place.

Walking past dimly lit rows of dusty, tan microfilm cabinets, I finally found a drawer labeled in pencil “FBI Fiche 1941-1986.” And on opening the drawer, I gleefully saw thousands of not FBI fiche, but FBIS fiche, the mother lode. There were fiche records not only from China, but from Japan, the Soviet Union, Israel, Brazil, India and South Africa. In front of me, and in tiny images about half-an-inch tall, were the documentary histories of a host of significant events—as they happened—including the U.S. Occupation of Japan, Cuban Missile Crisis, Six-Day War, assassination of Gandhi and South African apartheid at its height. As I stood looking at FBIS fiche incorrectly labeled “FBI,” I wondered how many people opened the drawer looking for J. Edgar’s old FBI records, only to be disappointed. Then I wondered how many people kept walking past this drawer and missed finding the secrets hidden in the FBIS Daily Reports, just because of one missing “S”?

Grabbing a large handful of China Report fiche, I retreated to the relative sanctuary of central heat and clean air in the reader room, which had four aging microfiche readers. The FBIS Daily Report: People’s Republic of China, January 19, 1956, was the first fiche loaded into the machine, and I started to read. And read. And read. I scrolled the glass plate around in circles, my eyes scanning for any reference to Chairman Mao, Mao Zedong or Mao Tse Tsung (the former being the pinyin romanization of Mao’s Chinese name; the latter being the older Wade-Giles Romanization). I took notes in my Trapper Keeper and fed dimes into the attached fiche printer.

After six more hours I was dizzy from continually scrolling the out-of-focus images past my eyes, yet I had only gotten through a year and a half of reports on China. I had a mini-compilation of Mao’s speeches during 1956, but felt no closer to understanding his eventual influence on an entire country. However, after reading more than 300 FBIS Daily Reports, I thought I knew how local Chinese must have felt and thought on a myriad of subjects in 1956. The constant propaganda machine and political barrage glorifying the benefits of Communism and the evils of capitalism left me pondering the power and influence media had on its population and the role it played. After this research I had an indication, but no concrete proof, of the Chinese Communist Party’s influence on local media and its use to incite revolution.

Eventually I completed my research after many more hours reading FBIS reports and even a trip to the Asian Studies section at the Library of Congress (LoC). I expected the LoC to have a wealth of useful material, but most of it was in Chinese, which I couldn’t read. So I kept reverting back to the English translations of the FBIS Reports. In my final thesis, I cited the centralized control of the media—and specifically radio—by loyal Mao sympathizers as one of the main reasons Mao was able to build his personality cult. Admittedly the proof and citations were a bit thin, but I felt I had done my best with the resources and technology available at the time.

The modern researcher

Jump forward 20 years. Technology has, in the past seven years alone, completely revolutionized research through digitization. The ability to mass-scan documents and convert printed words into machine-searchable text opens an entirely new and productive era in modern research. Documents that once had to be read page-by-page for a particular person, place or thing can now be searched in an instant. Researchers who once had to pay thousands of dollars and spend weeks traveling to use another library’s collections can now access many libraries’ holdings from their own desk. Through digitization, modern researchers can investigate a greater number of sources—producing more accurate and authoritative results—in a fraction of the time it once took. As a result, the quality and the quantity of valuable research now being produced is immense.

Take FBIS for example. Eight years ago, Readex made the decision to index, categorize and digitize the entire collection of Foreign Broadcast Information Service Daily Reports for its entire run, from 1941 to 1996. Created from original paper copies and high-quality microfilm, the digital edition includes more than eight million articles that can quickly be searched by person, type, location, date or event.

In less than five seconds, I can now display every single reference by or about Mao Zhedong, Mao Zedong or Mao Tse Tsung in any media outlet from 100 countries around the world, during Mao’s entire lifespan, all in or translated into English. The amount of time, money and resources saved compared to the old manual way of reading every document is incalculable. Thinking back now to my original thesis 25 years ago, I wonder whether my conclusions and supporting proof would have been considerably different had I today’s capability to discover relevant information.

What is more amazing is the fact that these resources have been around for more than 70 years, freely available for anyone who wanted to take the time and make the effort to search them. But unless one knew exactly where to look and when—a nearly impossible task given the lack of an index—making discoveries was a game of chance, much like an archeological dig. Digitization is to modern research what ground-penetrating radar is to modern archaeology.

The flip side of this advantage is that many of today’s students don’t even know what microfiche or microfilm is, let alone how to find and search them. The common refrain is, “If it isn’t searchable on the web, it isn’t available.” And as a result, many students don’t take advantage of the old media or know it exists. So unless Google, a private library or a commercial publisher decides to make the significant investment to digitize documents, there are still a lot of secrets buried in those old dusty tan cabinets that have yet to be discovered.

Postscript

For those who are curious, the goals of the “Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution” were clarified in a 16-point decision issued by the CCP Plenary Session on August 8, 1966. The first point of the decision, as disseminated by the New China News Agency and translated by FBIS staff, explained the situation to the Chinese people:

“At the 10th Plenary Session of the Eighth CCP Central Committee, Chairman Mao said: To overthrow a state power, it is always necessary, first of all, to create public opinion and to do ideological work...At present our aim is to topple those who are in power and who follow the capitalist road, to criticize the bourgeois reactionary 'Authorities' in the field of academics, to criticize the ideology of the bourgeois and all exploiting classes, to transform education, literature, art and the superstructure which is incompatible with the socialist economic base so as to consolidate and develop the socialist system.”

Several months after the start of the Cultural Revolution, FBIS specialists noted that many provincial radio stations stopped broadcasting locally produced programs, and were instead relaying communist-controlled material from Radio Peking. Analysts studying this development concluded that the behavior of local stations indicated which faction held the upper hand in the struggle for local dominance.

This insight into the provincial radio shutdowns and the crucial importance of these transmitters in the leadership struggle was later substantiated when a year-old CCP Central Committee notice (contained in an unobtrusive Red Guard publication) became available in 1968. The party directive decreed that “revolutionary masses” struggling against those in control of the radio stations must withdraw and conduct their struggles “away from the broadcasting stations.” It further ordered the local army command to assume responsibility for such stations and insure they “cease to edit and broadcast local programs and only rebroadcast the programs of Radio Peking.”

Red Guard newspapers and wall posters, although not usually available to Western eyes until long after publication, contained similarly important and unique information. They frequently provided detailed accounts of behind-the-scene developments, including several unpublished speeches by Mao. One such example is an FBIS- translated speech that Chairman Mao gave to a meeting of party functionaries on October 24, 1966:

"Nobody had thought, and I had not expected, that a single big-character poster, a Red Guard, and one big exchange of revolutionary experiences would create such turmoil in various cities…the Central Committee should be held responsible. The localities should be held responsible."

That was 1966. Little did he know at the time that the turmoil was only just beginning.