Researching Nat Turner's Slave Revolt in American (and African American) Newspapers

Nat Turner preaches religion. Image Credit: The Granger Collection, New York

Whites throughout the American South were traumatized in the summer of 1831 by a bloody slave revolt led by Nat Turner, a man his fellow slaves called “The Prophet.” By all accounts, Turner was an intelligent but peculiar man. Although education for slaves was widely outlawed, he taught himself to read as a young child and pored over the Bible. He often avoided people and spent much time fasting, praying, and preaching to other slaves. Turner believed he received visions from God—one vision instructed him to be an instrument of revenge against whites for their wicked ways.

The Capture of Nat Turner (1800-1831) by Benjamin Phipps on 30 October 1831

Beginning on Aug. 21, 1831, Turner led as many as 70 followers on a 36-hour rampage to free slaves and kill whites in Southampton County, Virginia. By the time the local militia rallied and scattered Turner’s band, 55 whites—31 of them infants and children—were dead, most of them butchered. Although the local militia defeated Turner’s band the next day and captured several of the rebels, Turner himself escaped and hid in the woods, avoiding capture for over two months. On Oct. 30 he was discovered and apprehended. On Nov. 5, Turner was convicted and sentenced to die; six days later he was executed.

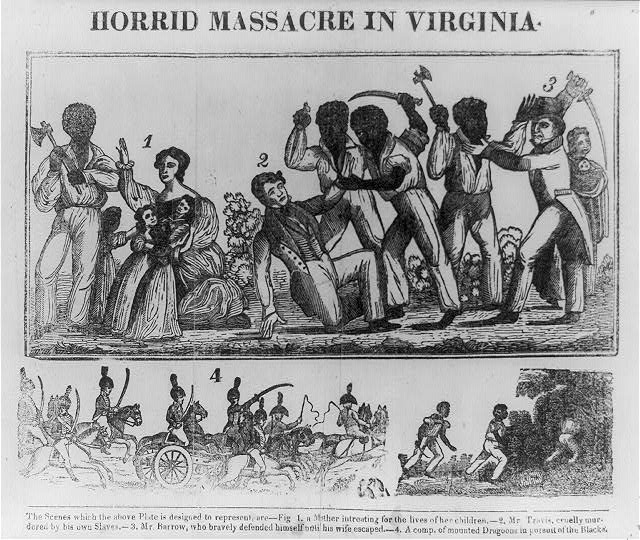

1831 woodcut from the book, Authentic and Impartial Narrative of the Tragical Scene Which Was Witnessed in Southampton County

Nat Turner’s rebellion, capture, trial and hanging were big news, especially in Southern newspapers. This article was printed by the Petersburg Intelligencer (Petersburg, Virginia) and reprinted by the Baltimore Gazette and Daily Advertiser (Baltimore, Maryland) on Nov. 5, 1831:

Capture of Nat Turner

The Petersburg Intelligencer received this morning contains the following account of this individual:

It is with much gratification we inform the public, that the sole contriver and leader of the late insurrection in Southampton—concerning whom such a hue and cry has been kept up for months, and so many false reports circulated—the murderer Nat Turner, has at last been taken and safely lodged in prison.

It appears that on Sunday morning last, Mr. Phipps, having his gun, and going over the land of Mr. Francis (one of the first victims of the hellish crew), came to a place where a number of pines had been cut down, and perceiving a slight motion among them, cautiously approached, and when within a few yards, discovered the villain who had so long eluded pursuit, endeavoring to ensconce himself in a kind of cave, the mouth of which was concealed with brush. Mr. P. raised his gun to fire; but Nat hailed him and offered to surrender. Mr. P. ordered him to give up his arms; Nat then threw away an old sword, which it seems was the only weapon he had. The prisoner, as his captor came up, submissively laid himself on the ground, and was thus securely tied—not making the least resistance!

Mr. P. took Nat to his own residence, where he kept him until Monday morning—and having apprized his neighbors of his success, a considerable party accompanied him and his prisoner to Jerusalem, where after a brief examination, the culprit was committed to jail.

Our informant (one of our own citizens, who happened to be in the county at the time), awards much praise to the people of Southampton for their forbearance on this occasion. He says that not the least personal violence was offered to Nat—who seemed, indeed, one of the most miserable objects he ever beheld—dejected, emaciated and ragged. The poor wretch, we learn, admits all that has been alleged against him—says that he has at no time been five miles from the scene of his atrocities; and that he has frequently wished to give himself up, but could never summon sufficient resolution!

Mr. Phipps, as the sole captor of Nat, is alone entitled to the several rewards (amounting in the aggregate, as we understand, to about $1,100) offered by the Commonwealth and different gentlemen, for his apprehension; and we are told, that in this instance Fortune has favored a very deserving individual—to whom, in addition to the pleasure arising from the recollection of the deed, the money derived from it will not be unacceptable.

This article was printed by the Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, Virginia) on Nov. 8, 1831:

Extract of a Letter Received in Richmond Dated Southampton, Nov. 1. Nat Turner is at last safely lodged in jail. He answers exactly the description annexed to the Governor’s Proclamation, except that he is of a darker hue, and his eyes, though not large are prominent—they are very long, deeply seated in his head, and have rather a sinister expression. A more gloomy fanatic you have never heard of. He gave, apparently with great candor, a history of the operations of his mind for many years past, of the signs he saw, the spirit he conversed with; of his prayers, fastings, and watchings, and of his supernatural powers and gifts, in curing diseases, controlling the weather, &c. These he considered for a long time only as a call to superior righteousness; and it was not until rather more than a year ago that the idea of emancipating the blacks entered his mind. How this idea came, or in what manner it was connected with his signs, &c. I could not get him to explain in a manner at all satisfactory—notwithstanding I examined him closely upon this point he always seemed to mystify. He does not, however, pretend to conceal that he was the author of the design, and that he imparted it to five or six others, all of whom seemed prepared with ready minds and hands to engage in it. These were they who rendezvoused in the field near Travis’s. He says their only arms were hatchets and axes at the commencement—that he entered Travis’s house by an upper window, passed through his chamber, and going through the outer door into the yard to his followers, told them that the work was now open to them. One of them, Hark, went into the house and brought out three guns—they then commenced their horrid butchery, he, Nat, giving the first blow, with a hatchet, both to his master and mistress, as they lay asleep in bed. He says that indiscriminate massacre was not their intention after they obtained foothold, and was resorted to in the first instance to strike terror and alarm. Women and children would afterwards have been spared, and men too who ceased to resist.I had intended to enter into further particulars, and indeed to have given you a detailed statement of his confessions, but I understand a gentleman is engaged in taking them down verbatim from his own lips, with a view of gratifying public curiosity; I will not therefore forestall him.

On Nov. 8, three days before his execution, the Richmond Compiler (Richmond, Virginia) ran this article. It was reprinted by the Macon Telegraph (Macon, Georgia) in its Nov. 19, 1831, issue:

We understand that Nat Turner, the head of the Southampton Tragedy, was tried by the Court of that county on Saturday last. The evidence against him was clear and irresistible—he was condemned, and sentenced to be executed on Friday next. Will some future fatalist pretend to assert of him, as a Romancer of Albany has lately said of Gabriel, that he was torn to pieces by horses? We need scarcely add, that these remarkable executions are unknown in Virginia—that the insurgent, like any other murderer, dies by the cord—and that Nat Turner will be hung as were his associates in the massacre of Southampton.

This notice was printed by the State Rights Free Trade (Charleston, South Carolina) on Nov. 14, 1831:

A Virginia paper says: “The speedy retribution which has overtaken Nat Turner and his murderous accomplices will be an awful warning to such deluded wretches forever hereafter. Not one has escaped!”

The Richmond Enquirer (Richmond, Virginia) ran this article in its Nov. 18, 1831, issue:

Nat Turner.—This wretched culprit expiated his crimes (crimes at the bare mention of which the blood runs cold) on Friday last. He betrayed no emotion, but appeared to be utterly reckless in the awful fate that awaited him, and even hurried the executioner in the performance of his duty! Precisely at 12 o’clock he was launched into eternity. There were but a few people to see him hanged. [Apropos—The Albany biographer of negro cut-throats will please to remember, that Nat was not torn limbless by horses, but simply “hanged by the neck till he was dead.” He may say, however, that General Nat sold his body for dissection, and spent the money in ginger cakes.] A gentleman of Jerusalem has taken down his confession, which he intends to publish with an accurate likeness of the brigand, taken by Mr. John Crawley, portrait painter of this town, to be lithographed by Endicott & Swett, of Baltimore. [Norfolk Herald.]

Refusing all entreaties to say a final word, Turner went calmly to his death. When they tightened the rope, he took a last breath and passed away without a kick or twitch, much to the crowd’s astonishment. This remarkable death scene was noted in this article, printed by the National Gazette and Literary Register (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) in its Nov. 19, 1831, issue:

Nat Turner.—We learn, says the Petersburg Intelligencer, by a gentleman from Southampton, that the fanatical murderer, Nat Turner, was executed according to sentence, at Jerusalem Friday last, about 1 o’clock. He exhibited the utmost composure throughout the whole ceremony; and although assured that he might if he thought proper, address the immense crowd assembled on the occasion, declined availing himself of the privilege, and told the sheriff in a firm voice that he was ready. Not a limb nor a muscle was observed to move. His body, after death, was given over to the Surgeons for dissection.

This comment was printed by the City Gazette & Commercial Daily Advertiser (Charleston, South Carolina) in its Nov. 21, 1831, issue:

Nat Turner, the somewhat notorious, was hung at Norfolk on the 11th inst. He met his fate with a stupid sort of indifference—sold his body to the surgeons for dissection, and spent the money in ginger-cakes!

African-American newspapers printed in the latter half of the nineteenth century provide a different perspective on Nat Turner. Turner is viewed as a hero in the following examples, one a poem and the other an oration.

This poem was printed by the Cleveland Gazette (Cleveland, Ohio) on Nov. 22, 1884:

Nat Turner By T. Thomas Fortune. He stood erect, a man as proud As ever to a tyrant bowed Unwilling head or bent a knee, And longed, while bending, to be free; And o’er his ebon features came A shadow—’twas of manly shame— Aye, shame that he should wear a chain And feel his manhood writhed with pain, Doomed to a life of plodding toil, Shamefully rooted to the soil! He stood erect; his eyes flashed fire; His robust form convulsed with ire; “I will be free! I will be free! Or, fighting, die a man!” cried he. Virginia’s hills were lit at night— The slave had risen in his might; And far and near Nat’s wail went forth, To South and East, and West and North, And strong men trembled in their power, And weak men felt ’twas now their hour. “I will be free! I will be free! Or, fighting, die a man!” cried he. The tyrant’s arm was all too strong, Had swayed dominion all too long; And so the hero met his end As all who fall as Freedom’s friend. The blow he struck shook slavery’s throne; His cause was just, e’en skeptics own; And round his lowly grave soon swarmed Freedom’s brave hosts for freedom arm’d. That host was swollen by Nat’s kin To fight for Freedom, Freedom win, Upon the soil that spurned his cry: “I will be free, or I will die!” Let tyrants quake, e’en in their power, For sure will come the awful hour When they must give an answer, why Heroes in chains should basely die, Instead of rushing to the field And counting battle ere they yield.

This oration was printed by the New York Age (New York, New York) on the front page of its Dec. 28, 1889, issue:

Nat Turner A Senior Oration by a Student of the New York City College Arthur W. Handy is a young man who graduated from Grammar School No. 81, of which Prof. Charles L. Reason is principal, some few years ago and entered the New York City College. He is at present a member of the graduating class and a candidate for the post of class orator next June. The following is his senior oration, entitled “A Hero,” it being one of three essays, limited to 550 words each, required to decide who shall occupy the position so highly prized. “In every age, in every clime, heroes have arisen. Men who have laid down family ties, honor, and even life itself for the maintenance of a principle. Men whose courage and devotion under the most trying circumstances have caused mankind to wonder in silent admiration. The world knows nothing of some of its greatest heroes, for there are forms of greatness which die and make no sign. There are martyrs that miss the palm, but not the stake. Heroes without the laurels and conquerors without the triumph. It has been said and said truly that the times make the man. Greece had her Leonidas, Rome her Horatius and England her Cromwell: Nathaniel Turner was a hero! Characterized from the rest of his down-trodden brethren by natural aptitude, by dint of hard work in secret places Turner learned to read and write. “Exercising his knowledge by reading such documents as the Right to Petition, Turner’s eyes were opened. He saw that all men were created free and equal. Immediately like a flash of lightning his whole being was suffused with a noble idea. Like Joan of Arc, he saw his mission in the flash of meteors, he heard his summons in the roaring of the wind. Collecting about him those whom he could trust, he planned a formidable uprising stretching from the land of Dixie to the palmetto groves of South Carolina. Slowly but surely the movement progressed. The time at last arrived when the blow was to have been struck. When the slave with sword in hand was to strike one blow for liberty. Was it done? Your histories do not record it. Nathaniel Turner was betrayed and by one of his own number. And yet how history repeats itself. How many such causes have been lost through treachery. Yet he died like a hero. No murmur escaped his lips. No sigh of regret for the failure of his plans. “With his death ceased all such attempts for freedom until the immortal John Brown took up the cause. And yet how different were the surroundings of these two men, and still both aimed at the same result. Turner alone, friendless, with nothing but his ignorant companions to cheer him in the mighty struggle, worked with undaunted fortitude. Brown was watched and encouraged by a host of admiring friends. Thousands of dollars were appropriated for his scheme and some of the noblest spirits on this continent bade him God-speed. How strange it is that these two men, brought up under such different influences, should have been animated by the same desire. The crime for which Brown died at Harper’s Ferry was identical with the one for which Turner died in South Carolina [sic], the means by which it was to have been accomplished the same. And yet all the world unites in giving glory and honor to Brown while Turner is forgotten. “Let those of us in whom the love of humanity responds to the spirit of the Bard Burns, who in his ‘Honest Poverty’ declares that ‘a man’s a man for a’ that,’ lift the veil of obscurity that shrouds the deeds of black men at the South. When the Nation’s history shall be written in the days to come Nathan Hale and Crispus Attucks will be accorded places side by side. May we not hope that John Brown and Nathaniel Turner will be surrounded with an equal halo of glory? Then rest in peace, thou more than hero, in other ages, in distant climes, when truth shall get a hearing, thy name shall be mentioned with reverence and with honor.”

While he was in jail, Turner had lengthy conversations with his lawyer, Thomas Ruffin Gray, from November 1-3, 1831. After Turner’s execution Gray published The Confessions of Nat Turner, which is thought to have sold over 50,000 copies in its first few months. An online edition of this book’s first edition can be read in the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s “DigitalCommons.”