“Shed Underwear Says Suffragist": Fashion as Social Commentary in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries

A recent journey into the Readex archives reveals just how much clothing and fashion informed social, political, religious, and health opinions and commentaries in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Health and Well-Being

Clothing is an aspect of fashion, but not all clothing. Fashion is more than clothing. The correlation of clothing and the materials with which it is made to physical well-being has long been a valid concern for public health officials specifically because the materials could provide a suitable environment for communicable disease vectors. A parallel concern is particular to fashion and the potentially ruinous effects it could have on a person’s health and morality. The former issue is clear in a printed order issued by the New York [City] Committee of Health in 1793 in response to the Yellow Fever epidemic in Philadelphia.

In 1806 Shadrach Ricketson, an obscure Quaker physician in the Hudson Valley of New York, published a book titled Means of Preserving Health and Preventing Disease Founded principally on an Attention to Air and Climate, Drink, Food, Sleep, Exercise, Clothing, Passions of the Mind, and Retentions and Excretions. One chapter is dedicated to clothing in which he lauds flannel as an excellent fabric to wear next to the skin.

Flannel is cheaper, and more comfortable; and generally far more healthy than linen, especially in cold seasons and variable climates; in which times and places, it should, by all means, be worn next to the skin.

A flannel shirt is both an excellent preventive and remedy in rheumatic and asthmatic disorders; and in all others, occasioned or supported by an obstructed perspiration; and has not improperly been termed one of the greatest preservatives of health.

Flannel drawers, as well as flannel shirts, are so conducive to health and comfort, in cold weather, and in variable climates and seasons, that I can no less recommend the former than the latter, to the female, as well as to the male sex, especially, as they arrive at the age of puberty.

Religion, "Morality", and Fashion

H.L. Mencken is generally thought to be the source of one definition of Puritanism, to wit: “Puritanism – The haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.” That appears to have been the inspiration for many religious diatribes against women who sought to adorn themselves. An anonymous tract, published in 1722: “Hoop-Petticoats Arraigned and Condemned by the Light of Nature, and Law of God.”, lamented the sin of pride particularly as manifested “in our Apparel, in following vain and sinful fashions, and particularly that vain, sinful, immodest one of Hoop-Petticoats.” The author fumes against proud women and cites the Bible for proof of their iniquity essentially condemning women who flaunt their fashions as tactless. He does allow that “I will not say there is none honest that wear them [hoops], but I may venture to say, without any Breach of Charity, that this no Sign of their Honesty or Purity, and I think there is no Loveliness in them; and I am sure they are not of good Report among the most judicious Persons: Therefore what Vertue [sic] or Praise I beseech you is there in them: Are these then as becometh Women professing Godliness.”

A somewhat kinder but highly specific consideration of the subject was offered by John Wesley in his Advice to the People Called Methodists, with Regard to Dress published in 1808.

Shall I be more particular still? Then I exhort all those, who desire me to watch over their souls, wear no gold, (whatever officers of state may do; or magistrates, as the ensigns of their office) no pearls or precious stones; use no curling of hair, or costly apparel, how grave soever. I advise those who are able to receive this; saying buy no velvets, no silks, no fine linen, no superfluities, no mere ornaments, though ever so much in fashion. Wear nothing, though you may have it already, which is of a glaring colour, or which is in any kind gay, glistering, showy; nothing made in the very height of fashion, nothing apt to attract the eyes of the bystanders. I do not advise women to wear rings, ear-rings, necklaces, lace, (of whatever kind or colour,) or ruffles, which by little and little may easily shoot out from one to twelve inches deep. Neither do I advise men to wear coloured waistcoats, shining stockings, glittering or costly buckles or buttons, either on their coats, or in their sleeves, any more than gay, fashionable or expensive perukes. It is true, these are little, very little things; they are not worth defending; therefore give them up, let them drop, throw them away without another word. Else a little needle may cause much pain in your flesh, a little self-indulgence much hurt to your soul.

These men were concerned with the moral health of their congregations, although the anonymous author fretted a bit about air circulating within the hoopskirts which he thought harmful to physical well-being. Many more opinions were offered regarding the physical dangers which were engendered both by the materials selected for the garments and particular fashions into which they were transformed. Warmth and perspiration figured large in these concerns. The Concord Observer of Massachusetts published an article on March 5, 1823 under the headline “Warm Clothing.” In which the author states the case for heat and sweat. One authority he cites for his “favorite recipe for health [which] was to leave off our winter clothing on midsummer day, but resume it the day following.” The essence of the theory behind the advocacy for warm clothing is:

To preserve health there must be a sufficient degree of heat to promote the generation of new juices as the old are discharged: constant perspiration is necessary, and this in a great measure is kept up by our clothing. A plant or vegetable will die if perspiration be stopped; an egg covered with varnish cannot perspire and will not hatch.

Health and Well-Being, Part 2: Social Views Disguised as Health Concerns

A grim expansion on the theory of perspiring for health was published by the Rhode-Island American of Providence on December 27, 1825. There is a sort of misogynistic and accusatory attitude toward women expressed as concern for their welfare.

While we thus enjoin upon all to cultivate habits of free and regular exercise, we would caution those of fragile or impared [sic] constitutions, against using it so as to occasion a great degree of heat or fatigue. To do good, it must be regularly, daily and perseveringly made use of, so as to keep up insensible perspiration. It is the interruption of this process, rendered certain by the flimsy wardrobe n which fashion requires those who are devoted to her service always to appear, that we trace the origin of those fatal diseases which are constantly making such cruel ravages among those who contribute most to the life ornament of social and domestick [sic] intercourse… the names are already too numerous of those who have fallen victims to the deadly influence of that insidious class of diseases, which preys with the most unsparing voracity upon the fairest and dearest part of nature’s work.

One further grim report appeared in the Boston Traveler on October 14, 1828 here in full:

Intemperance in Clothing. Dr. Reese points out the ill effects on health of tight lacing, and remarks that almost every professional man has witnessed the fatal results of this abomination. He dissected the bodies of two young females who had died of disease caused by tight lacing, and found ‘the adhesion of parts and the derangement of structure truly frightful.’ He adds, ‘the ingenuity of the ladies, perhaps, could not be better exerted than in contriving some method of preventing such havock [sic] as is annually occasioned among them from tight lacing and thin dressing.’

Asserting Women's Rights through Fashion

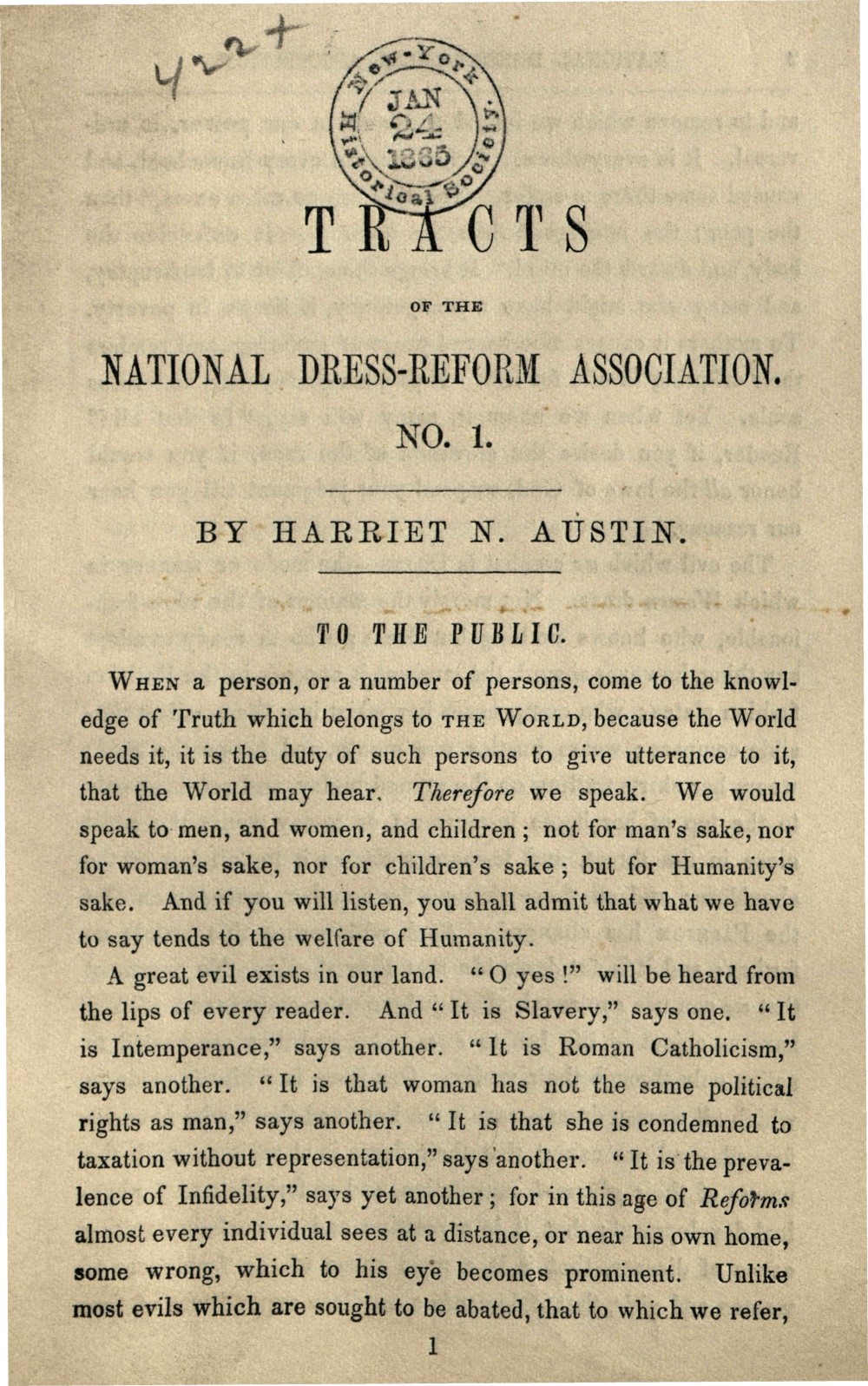

Harriet N. Austin was the sort of ingenuous woman Dr. Reese hoped for. Born in 1826, she became a hydrotherapist because women could not attend medical schools. She was a vegetarian, a hygienist, and, notably, the designer of the “American costume” (sometimes “Reform Dress”) for women. In 1851 her proposal for dress reform was published in a pamphlet from the National Dress Reform Association. After dismissing the silliness of the small number of women who are slaves to fashion, she avers:

Our issue is with the mode in which all women dress – save a few here and there who have reformed – and we assert that their dress is at variance with the nature of their physical constitutions, and so forbids a true physical development; that it is a positive and powerfully exciting cause of disease, that it is a main cause of the feebleness of women and girls, that it demands a needless expenditure of time and money… The first object is to secure the person against immodest exposure; the second is to preserve against all atmospheric changes, the temperature of the body at a healthful standard. While these are the principal objects of dress, other things, such as the gratification of the endless variety of tastes, may be taken into account in its construction, but never in such a way as to pervert its main uses, or interfere with the natural and free action of any of the organs of the body, or to require so much time and thought as to prevent proper activity and growth in any other department.

The entire pamphlet is a radical assertion of the rights of women. Couched in a careful deference to propriety and sensitivity to social forces, it is no less passionate and fearless.

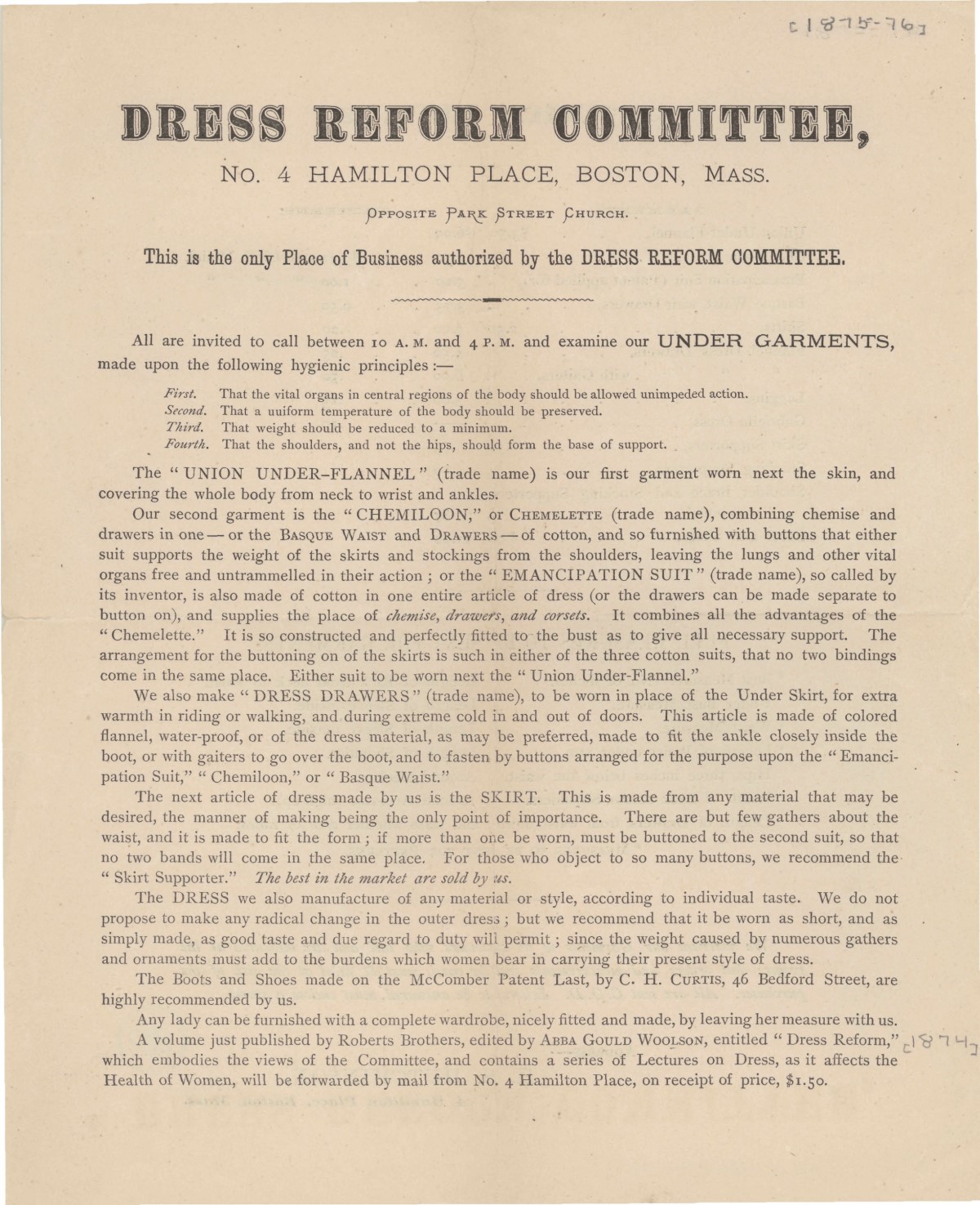

By 1875, one H.S. Hutchinson was advertising his store in Boston as “the only place of business authorized by the Dress Reform Committee.” His stock included the Union Under-Flannel, the Chemiloon (combing chemise and drawers in one), the Emancipation Suit (chemise, drawers, and corset combined), and Dress Drawers.

Back to Health Concerns

The issue of how warmly people should or should not dress persisted. The Philadelphia Inquirer reprinted an article from Life Illustrated on January 15, 1857,

Hints upon Health – Clothing and Cold Catching”, warning that “excess clothing is an evil, and is really one of the most frequent causes of a feeble, sensitive, and morbidly susceptible skin, and consequent suffering from exposure to sudden or great alterations of temperature.

The writer is especially concerned that necks not be too warm.

The most prevalent error in dress is too little about the feet and too much about the neck and chest. Since heavy neckerchiefs have been in fashion, throat ails and quinsys have multiplied correspondingly. We have known many persons entirely cured of a tendency to frequent attacks of quinsy, by merely washing the neck each morning in cold water, and substituting a light ribbon around the shirt collar, for the repudiated heavy stock or thick cravat.

It appears that Life Illustrated: A Journal of Entertainment, Improvement, and Progress was published by three phrenologists between 1854 and 1861.

A German professor posited that sweat arose in two kinds, one of joy which is sweet smelling and one of anguish which is offensive. Further, he contended that wool clothing absorbed only the sweet sweat while clothes made of plant fiber absorbed only the offensive.

An article in the March 11, 1890 edition of the Oregonian began:

A wave of dogmatical nonsense about clothing has passed over the land lately, says the Sanitary Era.” The idea that the neck should not be too warm is quickly dispatched by the author whose rational advice is captured in the headline “Clothing and Common Sense. Proper Clothing Conducive to Good Health a Scientific Fact.

Edward B. Warman was a widely regarded as a health expert in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was an enthusiastic advocate of daily exercise as the foundation for good health. Not all of his ideas were nearly so sound. An article he had written for a publication named Health Culture was reprinted by the Springfield Republican in Massachusetts on August 22, 1900. The headline, “Health Influenced by Color”, and subheads, “Sunlight and the Human Body” and “Some Interesting Experiments with Clothing”, make clear his purpose.

Color of clothing? Yes. The color of your outer garments materially affects body and brain when you are exposed to the rays of the sun… I have no theories to offer, but, instead, the result of years of observation and experience. I trust my words may be timely and, if heeded, the reward in comfort, better health, better disposition, more sunshine in the home; these, all these, and more, will be yours.

He discourses on heat and light distinguishing the sun’s light from its rays.

Danger and destruction lurk in the heat of the sun, but not in its light. Excessive heat is destructive to man, beast and vegetation: but the light, what of it?

To his satisfaction he demonstrates the efficacious effects of sunlight on restoring and maintaining good health as proven by his experiment. In general, his conclusions seem sound, but he launches into a new realm when he states:

While I am a firm believer in the efficacy of chromopathy, I shall not now stop to cite its merits, but merely mention that certain drugs are affected detrimentally, or are benefitted, as the case may be, according to the color of the bottles in which they are kept… All drugs used for the purpose of soothing or quieting should be kept in blue bottles; all excitants in red; liver preparations in amber or yellow, etc. All patent medicines should be placed – in the sewer. A dark blue bottle, when filled with water and magnetized by the sun, and its contents taken inwardly, will have a decidedly different effect from that of water so served and so taken from an amber-colored bottle. Try it.

Chromopathy, is a discredited concept, a pseudotherapy. In a sense this was Warman’s patent medicine to be consigned to the sewer. He concludes his argument:

Before closing this article I would especially caution the ladies against wearing red veils, the most trying color to the eyes. Also avoid, for general use – that is, in a room regularly used – red wall paper, red curtains, red lamp-shades and red lambrequins. These should be avoided, if for no other reason than causing one to become color-blind.

When higher heels became fashionable for women, the Patriot of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, warned of their danger in a column published on August 27, 1906.

Compared with the fashionable shoe of the present day, the rawhide and leather sandals of our earliest forefathers were hygienic and sensible.

High heels elevate the body into an unnatural position.

To maintain the trunk at this false angle there is a certain amount of strain which has to be taken into account. The internal organs also are affected, and the danger of falling and twisting or jolting the delicate structures of the body is increased…

… Have you ever observed the peculiar gait of the girl who wears high heels?

She trips or jerks her feet into position in a peculiarly ugly, short stepped fashion, which is the direct result of loss of play in the ankle, toe and foot joints.

Any wearer of high heels knows their hideous effect on the toes.

The pointed toe is in part to blame for the twisting of the toe joints, the corns and bunions, which bring joy to the heart of the chiropodist.

Charles Zeublin was a prominent professor of sociology at the University of Chicago. He published and lectured widely. His ideas regarding dress and health were reported by the Idaho Register of Idaho Falls on January 27, 1914. The headline was provocative: “Wear Still Fewer Clothes.” The tone of the article is indicated in a subhead: “One Piece Rompers suggested for the Dear Things – Slit Skirts Means Emancipation.”

Shades of Eve! In the very teeth of the bitter criticism of the peek-a-boo waist, the diaphanous and slit skirt, and the sometimes more than half-back decolette [sic], comes a mere man timorous enough to declare that women wear too many clothes. Professor Charles Zeublin, famous scientist and lecturer of Worcester, contends that the human race would be healthier, happier and more moral if women wore fewer clothes.

The professor believed that a one-piece romper was “The best garment for each sex.” While he conceded that skirts could be added for women if custom dictated, but he asserted:

The elimination of skirts is obviously in process now. Petticoats have been abandoned, temporarily at least, and the slit skirt gives promise of a skirtless costume in the future. And the savings on skirt materials and petticoats makes expensive silk stockings available for a multitude of women. What economic possibilities the skirtless costume holds. Instead of being immoral, the slit skirt is a token of woman’s emancipation from sex subjection. If ultra-conservative people are shocked and ultra-vulgar people are ribald, it is because both prefer the subjection of women.

He further extols the diminishing grip that corsets had held on fashion which results in women’s figures being “when fully clothed, more nearly resemble the normal figure.” and concludes his argument:

The alleged danger to health by less clothing for the body will be abundantly cared for by superior circulation of the blood, better appetite, and more normal sleep. Oxford ties, pumps, and thin silk stockings on healthy women lead to such a circulation of the blood that they may be warmer than in the past. Decolette [sic] costumes when not extreme are appropriate in all but the severest weather if the wearers are in perfect health. The justification of the present modes for women is shown in the sufferings endured by men who are subjected to the present imbecile masculine garments.

Fashion Forward (Freedom in Fashion)

It is not surprising that the pendulum should swing and that in time the corset again be promoted as a fashionable necessity. “Is the Corset Coming Back?” asks a headline in the August 28, 1921 issue of the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Although corset checking rooms, where women may ‘park’ their corsets while they dance, have become quite the usual thing and a rapidly-increasing number of women are dispensing with the corset altogether, Paul Poiret, the great Parisian creator of fashions, declares that the corset is surely coming back… This view is rather surprising, for M. Poiret was formerly a relentless foe of the corset. Many years ago he led a vigorous campaign against it and maintained that women would be infinitely healthier and better looking if they never compressed their bodies into one of these ‘highly injurious contrivances.’

Where others found the unbounded female figure beautiful and natural, Poiret rued that “In my work of designing gowns I have discovered that, as a result of going without corsets, many of the women who were formerly among our most beautiful are fast becoming shapeless bags of flesh.”

Despite the designer’s cheerleading, the corset did not really come back.

To conclude on a grace note: Mary Edwards Walker, physician, Civil War surgeon, and Medal of Honor recipient, was an undaunted advocate of dress reform for women in the interest of their physical and moral health. She developed her own style of dress which included trousers, suspenders, even a top hat on occasion. She was repeatedly arrested for wearing men’s clothing but never backed down. Her advocacy and her personal manner and appearance are described in a rather light hearted manner by a reporter for the New York Tribune in an article reprinted by the Cincinnati Daily Gazette on May 26, 1877. The reporter describes being admitted to a meeting with Dr. Walker at her home.

With only one exception, the reporters were old. Sedate-looking men, who were expected to be improved by advice on ‘The Reform in Women’s dress.’ … She wore a coat and trousers of blue silk, a man’s hat, and patent leather shoes with thick soles. At her neck was a red rose. Her face is thin, but attractive, with a touch of color upon each cheek, and a pair of sparkling, laughing eyes. She has a profusion of long black curls. Her height is five feet two inches, her weight 100 pounds, and her age forty-one years.

Before beginning her lecture, she chatted with the reporters. ‘“I feel awful good in my chemiloon,’ she said, ‘and I wear suspenders too. Of course I do. Every morning I get into ‘my envelope,’ as we term our reformed dresses, and I don’t care for all creation.’

The Doctor then led her audience to the lecture room, where she described the evil effects, physically, of the present style of dress among women. Upon the walls were plates and diagrams, and upon the tables were models showing the deformities caused by fashionable clothing. The evils, she said, were both physical and moral. Tight lacing and heavy dresses and other clothing suspended from the hips caused falling of the womb and other diseases prevalent among women. There was not a woman to-day in this country, who dressed after the prevailing style who was not suffering to some extent from uterine diseases. The compression of the body produced abnormal and painful swellings in the chest and impeded the circulation of the blood. The bad consequences of wearing tight garters were also dwelt upon, and the advantages of trousers were emphatically asserted. The lecturer was very enthusiastic in her commendation of the attire of men as compared with that of woman.”

Doctor Walker was a trailblazer. With the possible exception of her top hat, her choices were logical and her position unwavering. By the time of her death in 1919, American women were freeing themselves from restrictive clothing and more often dressing for comfort and utility.