The Short Plays of Neglected Female Author Frances Aymar Mathews, a Contemporary of William Dean Howells and Edith Wharton

The most recent release of Nineteenth-Century American Drama includes most of the short plays, or comediettas in one act, by the prolific Frances Aymar Mathews. This understudied author was born in New York City in the middle of the 19th-century. She began publishing in the 1880s. In addition to plays, her written output included feature articles, short stories and such novels as My Lady Peggy Goes to Town and Allee Same.

The most recent release of Nineteenth-Century American Drama includes most of the short plays, or comediettas in one act, by the prolific Frances Aymar Mathews. This understudied author was born in New York City in the middle of the 19th-century. She began publishing in the 1880s. In addition to plays, her written output included feature articles, short stories and such novels as My Lady Peggy Goes to Town and Allee Same.

Eighteen of Mathews’ shorter plays are included in this release. When reading her works, Edith Wharton comes to mind. They were contemporaries, shared a Manhattan upbringing during the Gilded Age, and were sensitive to class distinctions and social niceties. It may be something of a stretch to compare Mathews to Jane Austen, but both women are close observers of the foibles of the prosperous and employ a satirical view of them. There is one more comparison to make, to wit, William Dean Howells. Again, this may be a stretch, but the famous Howells and the obscure Mathews wrote short plays which, as previously noted here, featured wealthy people with ample time to expand upon largely trivial events.

Mathews shared three other literary traits with Howells. Both wrote novels although his endure and hers do not. Both used titles that indicated the banality of their depictions of elevated lives. Hers include The Apartment, At the Grand Central, The Proposal, and The Wedding Tour. Each occasionally employed obscure vocabulary. In Mathews’ case, see gimcrack, chirography, and soubrette.

Mathews shared three other literary traits with Howells. Both wrote novels although his endure and hers do not. Both used titles that indicated the banality of their depictions of elevated lives. Hers include The Apartment, At the Grand Central, The Proposal, and The Wedding Tour. Each occasionally employed obscure vocabulary. In Mathews’ case, see gimcrack, chirography, and soubrette.

There are notable similarities among most of Mathews’ plays. Many of them seem formulaic, each running to ten pages. She is whimsical in the naming her characters and is fond of luxurious settings in New York City, Saratoga, Italy, and France. Although only three of her many newly digitized play will be considered here, it is a worthwhile endeavor to study all of them and to reconsider Mathews’ place in American theater.

At the Grand Central

This bit of fluff has an all-female cast: Miss Kitty Roland and Miss Pussie Oliver, obviously wealthy young ladies to the manner born.

[Scene.—A prominent position in the ladies’ waiting-room of the Hudson River Station. Pussie discovered seated with a novel in hand.

Pussie. [Glancing up and descrying KITTY advancing in the distance.] Dear me! how very disgusting, here comes that horrible Roland girl; I wonder if by any chance she has heard the news of my engagement being off? Guess not.

Kitty.—[Aside, as she advances toward PUSSIE.] If there isn’t that hateful Oliver girl! I don’t care! I’ll just go up and speak to her anyway. I do wonder if she could have heard of—how could she though! Quite impossible. [Steps briskly up to PUSSIE who rises effusively to meet her] My dear Miss Oliver, how do you do? I am so glad to meet you, such a lucky chance! [They kiss on either cheek.]

Pussie.—Mutual, I’m sure. Delighted, I was just dying of ennui and longing for the sight of a friendly face; sit down like a love—do!

Having settled themselves comfortably, Kitty and Pussie engage in a conversation which is ostensibly pleasant but rife with barbs and one-upmanship. Pussie inquires if Kitty has been “stopping” in town.

Pussie.—Oh, no; just for the day.

Kitty.—Shopping!

Pussie.—A little; and you?

Kitty—Dressmaker’s; trying on a couple of ball-gowns at Donovan’s.

Pussie.—Horrid bore!

Kitty.—Frightful. Been to see the pictures at the Academy?

Pussie.—Oh, of course; had to be done; went to the private view, did you?

Kitty.—No, couldn’t; had a tea and a dance at the Country Club.

Pussie. Jolly?

Kitty.—Bored to death…

Pussie.—Seen the Winter’s Tale?

Kitty.—No.

Pussie.—Mary’s costumes are exquisite.

Kitty.—[Opening box of bonbons]. Have some?

Pussie. Thanks, awfully. [Takes bonbon.]

As their conversation proceeds they manage to exhaust their supply of bonbons in what is intended as, and may work as, comic business. Kitty, who claims to have given up reading altogether, extols the new class she is attending, “the latest thing,” which is entitled “Patent Solidified and Condensed Quintessence of Mental.” When asked “what’s it for anyway?” Kitty describes the cramming effect of the class leader, Mrs. Smartseize. “I tell you she’s wonderful; why yesterday between two and four she made us perfectly familiar with ten new novels, two religious works, three political, eleven volumes of poems, the diplomatic situation of Europe for the past week; a dip in Court intrigue, and a dash at foreign art—not to speak of a spice of the sort of high-life scandal one really must be au courant with—in order to mingle intelligently with one’s set.”

They proceed to chat about art classes, riding classes, and weddings. They move on to Mrs. Panner’s cooking club which Kitty dismisses on account of the behavior of the five Miss Panners who “count every man that enters their doors, and won’t present one to any girl— ”

Pussie.—[Interrupting.] Come, now, that’s a little too hard; they have introduced a half-dozen to me.

Kitty.—Please allow me to finish—any girl who is in the least attractive.

During a discussion of the problem of inadvertently socializing with those who are not quite one’s type, Kitty discloses a rumor that Pussie’s mother used to be “a high-school teacher in Vermont.” Pussie offers the rumor that Kitty’s mother “used to make her own gowns.” Finally, Kitty reveals that she is engaged to the man with whom Pussie had barely broken her engagement. They have missed their train and resolve to go in search of “chocolate and tarts and pickles.” Pussie tries to ask Kitty if she really believed the rumor about her mother having been a teacher. Kitty waves this off.

Pussie.—I wouldn’t credit such a thing of you any more than I’d believe your mother had ever made her own dresses.

Kitty.—My angel, one’s just as true as the other. Come on.

They exit.

The Proposal

Elsie is impatient with Tom’s dilatory ways. She expects a proposal but is impatient. “Poor Tom. And why do I say “poor Tom?” He is the most unsatisfactory, exasperating, disagreeable—No! he isn’t disagreeable at all. He is—he is only very, well—unrapid.” She counts of her previous suitors. “Max proposed in a fortnight; Will, in ten days; Jack, in three; Charlie, the second time we met; Frank, in twenty-four hours—Tuxedo; and Roy—he took the longest; he was actually six weeks before he asked me. Preposterous waste of time!”

She laments that Tom has known her for a year. “It’s ridiculous—absurd. Besides when I recall the innumerable, excellent, propitious, provocative, delightful, delicious, beguiling chances that man has had to offer himself to me, I am simply stunned, amazed, annihilated by his lack of savoir faire in failing to embrace at least one of them—and me too.” She recounts all of the occasions and all of the locations at which Tom has failed to propose.

Tom arrives, and in a lengthy monologue typical of Mathews’ plays, reiterates all of the occasions which Elsie has detailed. He has had much too much to drink, and comic business ensues as he is first too hot and then too cold and then too hot as he opens and closes the window while he obsesses. Elsie enters and they lightly shadow box as Tom splutters and stutters finally to a proposal. She accepts and assures him that never betrayed the least nervousness telling him “You were just as brave and courageous, and—self-possessed—as I ever saw you in my life.”

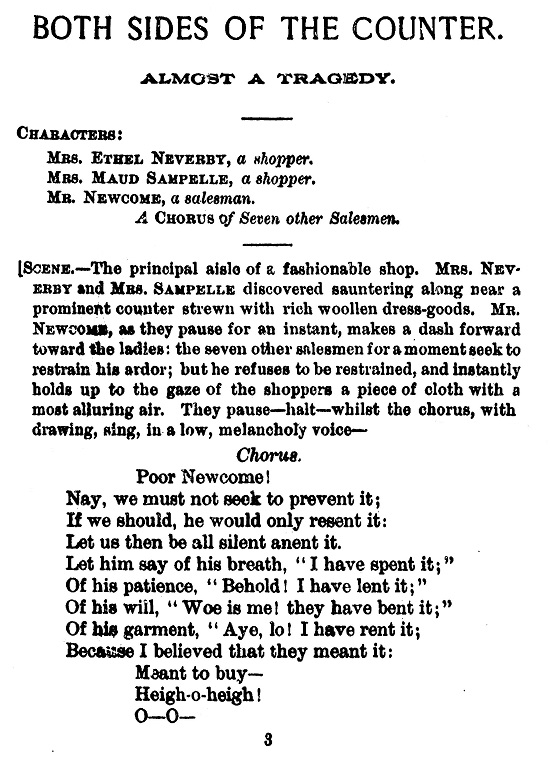

Both Sides of the Counter

This play is set in “a fashionable shop.” The characters are Mrs. Ethel Neverby, a shopper, Mrs. Maud Sampelle, a shopper, Mr. Newcome, a salesman, and intriguingly, A Chorus of Seven other Salesmen.

[Scene.—The principle aisle of a fashionable shop. Mrs. Neverby and Mrs. Sampelle discovered sauntering along near a prominent counter strewn with rich woolen dress-goods. Mr. Newcome, as they pause for an instant, makes a dash forward toward the ladies; the seven other salesmen for a moment seek to restrain his ardor; but he refuses to be restrained, and instantly holds up to the gaze of the shoppers a piece of cloth with a most alluring air. They pause—halt—whilst the chorus, withdrawing, sing, in a low melancholy voice—

Poor Newcome!

Nay, we must not seek to prevent it;

If we should, he would only resent it:

Let us then be all silent anent it.

Let him say of his breath, “I have spent it;”

Of his patience, “Behold! I have lent it;”

Of his will, “Woe is me! they have bent it;”

Of his garment, “Aye, lo! I have rent it;

Because I believed that they meant it:

Meant to buy—

Heigh-o-heigh!

O-O-

The chorus precisely sums up the play. As all the other salesman know, Ethel and Maud are notorious shoppers who consume the salesman’s time ad nauseum with no intention whatsoever of buying anything. This is their entertainment and they are highly practiced at it. They have Newcome exhaustingly dancing attendance on them, hauling down heavy bolts of fabric from the highest shelves, escorting them to the “gas-light room” in order for them to see how the colors appeared in that lighting. Their deceitful conceit is that they are shopping for a friend who is indisposed. This ruse allows them to perseverate over each decision which results only in no decision at all.

The chorus chimes in two more times. As they had foreseen, the ladies buy nothing. Newcome “falls to earth with a groan of despair,” and the chorus concludes:

Poor Newcome!

You are not the first man they have ended,

And left on the cold ground extended;

Or to whom they have sweetly pretended,

On whose taste they have weakly depended, -

Minus money they never expended,

On goods that they never intended

To buy,

Heigh-o, heigh’

O-O-!

Frances Amyar Mathews merits consideration as one of the relatively few women who succeeded as playwrights in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Her short plays have as much value, humor, and inventiveness as those of the literary giant Howells. Which is to say some substantial wit and a soupçon of inventiveness.

For more information about Nineteenth-Century American Drama, please contact Readex Marketing.