Tales of Brave Ulysses: General Grant’s World Tour, 1877-1879

General Ulysses S. Grant’s wife, Julia Dent Grant, enjoyed sharing the following anecdote about their epic voyage around the world. Her story emphasized a key difference between her husband and his namesake, that other intrepid man of arms. Incidentally it revealed that Julia was no less fond of adventure than the celebrated general and former president.

When they were sailing through the Mediterranean on the United States man-‘o-war Vandalia they passed the island celebrated in Homer’s verse as the home of the sirens, whither Ulysses was decoyed by these seductive ladies.

As their ship neared the island a number of the officers aboard went to Mrs. Grant and told her that she should look to it that her husband’s ears were stuffed with cotton, lest he, too, be enticed and led astray by the singing of these same beautiful creatures, whereupon Mrs. Grant laughingly informed the alarmists that the general was immune to the influence of singing, since he did not know one tune from another. But they insisted that these creatures were so beautiful that their faces, if not their voices, would win him. Mrs. Grant, however, with a brightness with which she was not always credited, replied that Homer’s Ulysses had been deluded because he had left his wife, Penelope, at home, while she, on the contrary, taking warning from that old tale, had accompanied her Ulysses, whom she felt sure would be protected by her presence even from the allurers who ensnared the classic Ulysses.

And so it was that apart from the endearments of his faithful wife, the most irresistible siren-songs heard by Ulysses S. Grant, hero of the American Civil War and two-term Republican president, emanated from the steam whistles, fog horns, and cannon salutes that heralded his arrival in yet another port during his and Mrs. Grant’s world tour. He embarked as a student of human nature and found that the world had discovered America anew as one nation, indivisible, and he himself as its foremost diplomat.

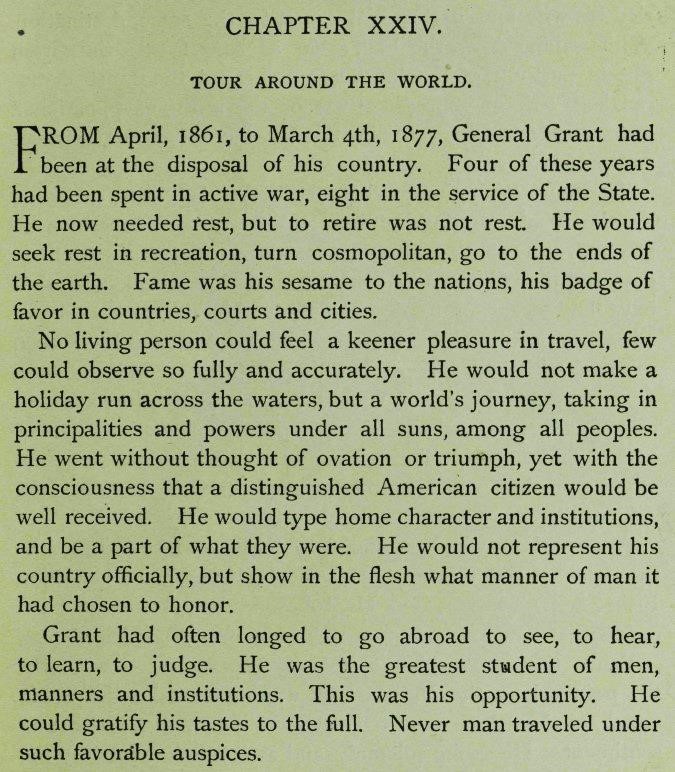

It’s understandable that an ex-president would step back from public life so as not to encroach upon the incoming president’s prerogative, even likely as a respite from the sheer exhaustion of serving as head of state. Grant, however, plunged enthusiastically into global politics, although he made it clear that he was traveling as a private citizen. The following comes from a biography of Grant found in Readex’s American Civil War Collection:

From April, 1861, to March 4th, 1877, General Grant had been at the disposal of his country. Four of these years had been spent in active war, eight in the service of the State. He now needed rest, but to retire was not rest. He would seek rest in recreation, turn cosmopolitan, go to the ends of the earth. Fame was his sesame to the nations, his badge of favor in countries, courts and cities.

No living person could feel a keener pleasure in travel, few could observe so fully and accurately. He would not make a holiday run across the waters, but a world’s journey, taking in principalities and powers under all suns, among all peoples. He went without thought of ovation or triumph, yet with the consciousness that a distinguished American citizen would be well received. He would type home character and institutions, and be a part of what they were. He would not represent his country officially, but show in the flesh what manner of man it had chosen to honor.

Grant had often longed to go abroad to see, to hear, to learn, to judge. He was the greatest student of men, manners and institutions. This was his opportunity. He could gratify his tastes to the full. Never man traveled under such favorable auspices.

Grant’s biographer mentions how Grant did not stand on ceremony in his preeminence. He had no particular desire to compete with royalty for official acclaim or popular adulation. He was graceful in paying honor where honor was due, in acknowledging the power and accomplishments of his peers around the world, but his preference was to indulge his curiosity rather than overindulge himself as a celebrity. From his days as a junior officer Grant had the common touch.

General and Mrs. Grant and their teenage son Jesse left Philadelphia on May 17, 1877, on the steamship Indiana. The first stop on their tour was Great Britain where they were received by Queen Victoria and stayed in Windsor Castle. But Grant still found time for the laboring classes.

On the 3d of July, General Grant received a deputation of workingmen, who presented him with an address of welcome in the name of their comrades throughout the United Kingdom. No honor, royal or civic, that he received during the whole three years’ tour, so touched the general’s heart, and he responded to it as follows:—

Gentlemen,—In the name of my country, I thank you for the address you have just presented to me. I feel it a great compliment paid to my government, to the former government, and one to me personally.

Since my arrival on British soil, I have received great attentions, and, as I feel, intended in the same way for my country. I have received attentions, and have had ovations, free handshakings, and presentations from different classes, and from the government, and from the controlling authorities of cities, and have been received in the cities by the populace.

But there is no reception I am prouder of than this one to-day. I recognize the fact that whatever there is of greatness in the United States, or indeed in any other country, is due to the labor performed. The laborer is the author of all greatness and wealth. Without labor there would be no government, or no leading class, or nothing to preserve. With us labor is regarded as highly respectable. When it is not so regarded, it is that man dishonors labor.

One reason Grant was well received is that in 1871 his administration had successfully arbitrated the settlement of the Alabama claims with Great Britain, putting in place what Americans refer to today as the “special relationship” with Britain. The British government expressed regret and paid $15.5 million for violating neutrality in allowing the Alabama and four other ships to be fitted up in British shipyards and used by the Confederate States as raiders on Union maritime commerce.

Grant, who had Scottish ancestry, received a gala welcome when visiting Edinburgh, although he was not as voluble as his hosts expected or desired. This next excerpt and many that follow are taken from reports by New York Herald journalist John Russell Young who was invited to travel with the Grants as special correspondent and describe their adventures. Young would later turn his dispatches into a lavishly illustrated two-volume book and serve as the seventh Librarian of Congress.

Eighteen hundred people, the highest toned of Edinburgh, were there—no boys or girls, but the heads of families—with tickets of admission sent to them outside of six thousand applications. The city dignitaries in robes, the soldiers in kilts, the insignia of office dotting the place and the gravity of the ceremony reminded one of the Queen’s visit to the House of Lords. That speeches were, as we say, “Fired off,” till, with a wave of the hand, the Lord Provost of Edinburgh delivered the silver casket—big enough for a sarcophagus—to the “Soldier, President, fellow Scot.” Then came cheers, and the collision of applauding hands shook the Gothic structure from base to roof. This was about his speech:—“The Lord Provost had welcomed him. He (General Grant) had no words to express his feelings personally. He never made speeches. Thanks for honors, thanks for overwhelming kindnesses. Plenty of Scotch citizens of America found it profitable to stay there. Come over and see us.” He spoke three-quarters of a minute.

The Grants visited Pompeii in Italy and climbed Mt. Vesuvius. They would return to Europe later in their journey, but first there was Egypt. Egypt was a revelation to General Grant and most certainly to his chronicler, Young. The following interlude is from their visit to the temple complex at Karnak.

You sit in the shadow of the column, sheltered from the imperious noonday sun—the same shade which, perhaps, sheltered Abraham as he sat and mused over his fortunes and yearned for his own land. The images are here; the legends are as legible as they were in his time. You sit in the shadow of the column, thinking about luncheon and home and your donkey, and hear the chattering of Arabs pressing relics upon you, or doing your part in merry, idle talk. It is hard to realize that in the infinite and awful past—in the days when the Lord came down to the earth and communed with men and gave His commandments—these columns and statues, these plinths and entablatures, these mighty bending walls, upon which Chaos has put its seal, were the shrines of a nation’s faith and sovereignty. Yet this is all told in stone.

Palestine and Jerusalem evoked a more subdued, personal response from the travelers than Egypt. Young made the point that history in Egypt was humanity writ large, whereas for Christians Palestine recalled the faith of their childhood and the sacraments of later life. Not that Grant’s party could entirely escape being a spectacle of its own. The general was able to gracefully refuse the fifty-piece band offered to him for his traverse over the Via Dolorosa, the path that Jesus Christ is believed to have walked on his way to crucifixion. Grant did, however, have to endure his own rendition of Palm Sunday when he (and before him, Jesus Christ) was celebrated as a prophet and savior when he entered Jerusalem. Young’s color commentary is a godsend:

We expected to enter Jerusalem in our quiet, plain way, pilgrims really coming to see the Holy City, filled with its renowned memories. But, lo and behold! Here is an army with banners, and we are commanded to enter as conquerors, in a triumphal manner! Well, I know of one in that company who looked with sorrow upon the pageant, and he it was for whom it was intended. But there was no help for it. So we assembled and were in due form presented, and there were coffee and cigars. More than all, there were horses—for the General, the Pacha’s own white Arab steed in housings of gold. It was well that this courtesy had been prompted, for the bridge over the brook was gone and our carts would have had a sorry business crossing. We set out, the General thinking, no doubt, that his campaign to enter Jerusalem at four had been frustrated by an enemy upon whom he had not counted. He had considered the weather, the roads, the endurance of the horses; but he had not considered that the Pacha meant to honor him as though he were another Alexander coming into a conquered town.

In France Grant received a cooler reception due to his support while president for the Germans over Louis Napoleon’s forces during the 1870-1871 Franco-Prussian War. Still, he managed to acquit himself well in a trial match of polo, a game he had never before played or even witnessed. It took place in Paris’ Bois de Boulogne. Grant was famous for his skill with horses and found much in the contest worthy of emulation as military training.

He looked remarkably well, and watched the game with deep interest. He had never seen polo played, and saw so much value in the game that he proposed to the ex-Minister that some morning early they would come out and have a trial game. I am not at liberty to state the result of this challenge, for I do not want to spread unnecessary alarm at home. Still there is this comfort, that if any of the Americans can take care of themselves on horseback or pony back with or without mallets it is our ex-President and our Ex-Minister to Austria [Edward Fitzgerald Beale]. General Grant noted the value of such a game as polo in the army, and at West Point especially, as improving the cavalry service.

Grant’s visit to Spain allows us to examine the protocol issues surrounding how to receive a foreign former chief executive and ranking military officer. It may seem a small matter to democratically-minded Americans, but especially in countries with dynastic succession that sought favor with America, the diplomatic etiquette presented challenges. Grant was insistent that he was traveling as a private citizen. He was not head of state and had no explicit authority or official agency. And yet he often arrived on a U.S. military vessel with a retinue of influential people. He was accorded honors that he found embarrassing in their munificence; he could not gracefully decline many of the courtesies and perquisites tendered to him. It was not a bad problem to have. Yet it was a problem in this rarefied atmosphere.

It’s customary to continue referring to ambassadors and dignitaries by their highest earned title, hence Secretary (Hillary) Clinton and so forth. But “President Grant” was not accurate after March 4, 1877, while “Ex-President Grant” overemphasized past glory. Spain met that dilemma by according Grant with Spanish military rank. Although he was in some sense required to meet with Spanish King Alfonso XII, he expressed particular interest in meeting a fellow ex-President, Spain’s Emilio Castelar.

There were officers in high grade who awaited the coming of General Grant. They came directly from the King, who was at Vittoria, some hours distant. Orders had been sent to receive our ex-President as a Captain General of the Spanish army. This question of how to receive an ex-President of the United States has been a source of tribulation in most European Cabinets, and its history may make an interesting chapter some day. Spain solved it by awarding the ex-President the highest military honors. More interesting by far than this was the meeting with Mr. Castelar, the ex-President of Spain. Mr. Castelar was in our train and on his way to San Sebastian. As soon as General Grant learned that he was among the group that gathered on the platform he sent word that he would like to know him. Mr. Castelar was presented to the General, and there was a brief and rapid conversation. The General thanked Mr. Castelar for all that he had done for the United States, for the many eloquent and noble words he had spoken for the North, and said he would have been very much disappointed to have visited Spain and not met him; that there was no man in Spain he was more anxious to meet.

We can’t leave Europe without noting Grant’s meeting with German Chancellor and Crown Prince Otto von Bismarck. The man who unified Germany had a great deal in common with the man who preserved the United States intact. They shared the respect for labor that Grant had expressed in Great Britain, as Bismarck had woven an alliance with labor to stave off socialism. The leaders also shared an aversion to war despite their own dominance in that arena.

“You are so happily placed,” replied the prince, “in America, that you need fear no wars. What always seemed so sad to me about your last great war was that you were fighting your own people. That is always so terrible in wars, so very hard.”

“But it had to be done,” said the general.

“Yes,” said the prince, “you had to save the Union, just as we had to save Germany.”

“Not only save the Union, but destroy slavery.”

“I suppose, however, the Union was the real sentiment, the dominant sentiment,” said the prince.

“In the beginning, yes,” said the general; “but as soon as slavery fired upon the flag, it was felt, we all felt, even those who did not object to slaves, that slavery must be destroyed. We felt that it was a stain upon the Union that men should be bought and sold like cattle.”

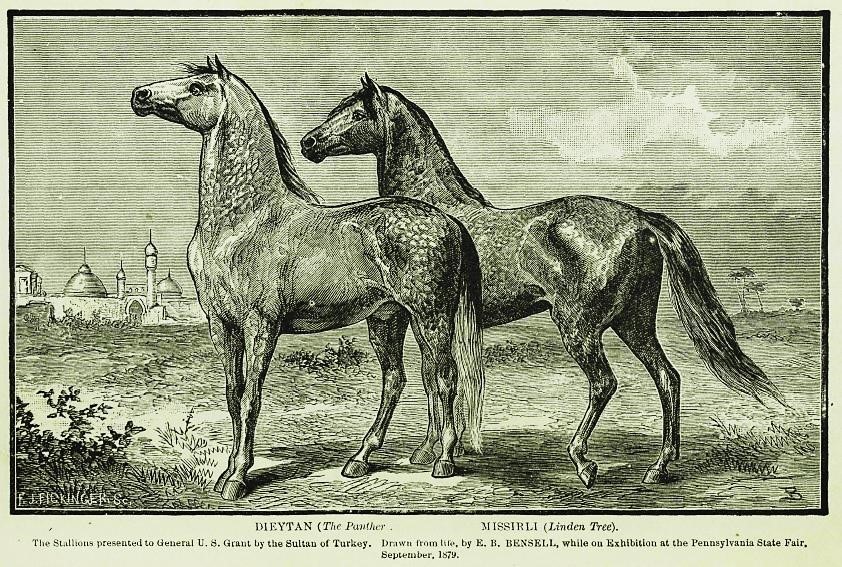

Beyond the preservation of the Union, America is indebted to Grant for the development of the American national horse. While Grant’s party was visiting Turkey Sultan Abdul Hamid II gifted the general with two fine Arabian stallions for which Arabian mares were later imported by Randolph Huntington, equestrian authority, breeder, and author. These animals formed an integral part of the breeding stock that has come down to us as a distinctly American horse. Huntington dedicated a book to Grant and credited him with the development of the breed. The following comes from an 1886 review of Huntington’s book, History in Brief of “Leopard” and “Linden,” General Grant’s Arabian Stallions:

President Polk and Secretary Seward received presents of Arabian horses from Turkey and Syria, but no pains were taken to preserve the purity of the breed.

But during his foreign tour Gen. Grant, while inspecting the choicest horses of the Sultan of Turkey, expressed his great admiration for the beautiful colt Leopard. It was at once given to him by the Sultan, together with another called Linden Tree, selected by the Sultan himself. Although Leopard has superior grace and beauty, Mr. Huntington thinks Linden the better horse, being more easy and steady. Of the purity of their breed Gen. Grant in 1882 wrote to Huntington that the pedigrees of all the horses in the Sultan’s stables from which these were taken ran back from 500 to 700 years.

Huntington believes, with Gen. Grant, that there is no reason why there should not be an American national horse, but to produce one, as Grant once remarked, “they must go to the primitive root, the same as did England, France and Russia—i.e., the Arabian.”

Life in India presented a curious dilemma for self-sufficient Americans who found the ubiquity of servants in India oppressive, though proffered with the best of intentions and nearly impossible to refuse without giving offense. The rank-and-file of Grant’s cohort was no less exempt from these attentions than was the general himself.

There is a minute division of labor and a profusion of laborers. When I began this paragraph it was my intention to say how many servants waited on me for instance in my own modest bungalow. But the calculation is beyond me. At my door there is always one in waiting, a comely, olive-tinted fellow, with a melting dark eye. If I move across the room he follows with noiseless step to anticipate my wishes. If I sit down to read or write I am conscious of a presence as of a shadow, and I look up and see him at my shoulder or looking in at the window awaiting a summons. If I look out of my bedchamber window toward the ocean I see below another native in a blue gown with a yellow turban. He wears a badge with a number. He is a policeman, and guards the rear of the bungalow. If I venture across the road to look in upon some of my friends a servant comes out of the shade of the tree with an umbrella. His duty is to keep off the sun. You cannot pass from house to house without a procession forming around you.

The General strolled over a few minutes ago with some letters for the post, and as I saw him coming it was a small procession—a scarlet servant running ahead to announce him, other scarlet servants in train. If you go out at night toward the Government House for dinner, one in scarlet stands up from under a tree with a lantern and pilots you over a road as clearly marked as your own door sill. In early morning, as you float from the land of dreams into the land of deeds, your first consciousness is of a presence leaning over your couch, with coffee or fruit or some intimation of morning.

A visit to Siam nearly resulted in tragedy. At this point in their journey the Americans were beginning to entertain thoughts of an early return home. A royal invitation to visit Siam arrived while the party was in Singapore. A lively discussion ensued as to whether to depart from the planned itinerary to visit Siam—Australia and New Zealand were also contemplated as destinations. But Grant decided that King Chulalongkorn’s invitation could not be graciously declined, and so it was accepted. They embarked on the small steamship Kong See rather than on their usual large American military vessel. Travel arrangements were improvised. When their pilot missed a channel into Paknam he dropped anchor in a stormy sea to await guidance. A royal yacht was dispatched and in due course arrived, but transferring the passengers to it presented problems.

We went on board the royal yacht in a fierce sea and under a pouring rain. There was almost an accident as the boat containing the General, Mrs. Grant and Mr. Borie came alongside. The high sea dashed the boat against the paddle wheels of the yacht, which were in motion. The movement of the paddle pressed the boat under the water, the efforts of the boatmen to extricate it were unavailing, and it seemed for a few minutes as if it would founder. But it righted, and the members of the party were taken on deck drenched with the sea and rain. This verging upon an accident had enough of the spirit of adventure about it to make it a theme of the day’s conversation, and we complimented Mrs. Grant upon her calmness and fortitude at a time when it seemed inevitable that she would be plunged into the sea under the moving paddles of a steamer.

The trip from Tientsin to Beijing, China, brought labyrinths of river navigation and court etiquette. Another momentary upset of a boat nearly resulted in the summary execution of its captain, an outcome prevented only by the intercession of the Americans. During this lengthy passage in a number of small craft up the shallow Peiho River both Americans and Chinese labored to make the time interesting for one other. Young relates the following encounter with their Chinese mandarin, the administrative official tasked with overseeing the Americans’ transit through his province.

You cannot say many things to a Chinese mandarin, no matter how civil you mean to be, when your medium is an interpreter and where there is really no common theme of conversation. You see that you are objects of wonder, of curiosity to each other. You cannot help regarding your Chinese friend as something to be studied, something you have come a long way to see, whose dress, manners, appearance amuse you. To him you are quite as curious. He looks down upon you. You are a barbarian. You belong to a lower grade in the social system. You have strength, rude energy, prowess; you have navies and fleets; you have battered down his forts and put your heel on his breast. You can do so again. But he has no respect for this power; for it is the teaching of all the sages that the military quality is the last to be honored, that war is not in any sense to be commended, and that the great nations whose power is in their armaments are none the less barbarous. To stand before a mandarin and feel that you are being studied as a type of rude and barbarous civilization is not conducive to talk, to such talk at least as you seek with men of your own race. You are so far apart in all things that there is no common theme upon which talk becomes useful. You tell him wonderful things; he tells you polite things—for nothing can surpass his politeness, his careless politeness, which runs along like the score of an opera, never missing a note.

A more spontaneous encounter came in the form of four small children of American missionaries working in Beijing. The group styled itself as “Us four” and contrived not only to learn the timing and gate by which Grant would enter the city borne upon an imperial chair, but also crafted four small American flags with which to semaphore their greetings. Grant was delighted by their earnest, enthusiastic welcome and invited them to a reception.

The General received the boys in the private parlors of the legation, and taking each one by the hand he introduced them to Mrs. Grant. There was no one else present, and the General gathered those four boys around him and told them how touched he felt by their welcome, and the sight of their little flags; how pleased he was to find them so full of fervor and patriotism, although living in a heathen land so far away from home. The boys sat in wonder as the soldier told them how proud they should be of their country, and closed with an exhortation for each one to prove himself a worthy American and to never do aught to disgrace his country. Shaking hands with his guests at the end, the General said: “Well, boys, if I ever write a book of my travels, I shall mention in it your welcome to me at the gates of Pekin.” And no prouder boys ever went from the presence of greatness than “us four” on that day.

Grant was asked by Prince Kung of China to act as an intermediary in presenting China’s claims for continuing tribute from the Loochoo Islands, known in modern times as the Ryukyu or Nansei Islands. This island chain includes Okinawa in which the United States retains military interests today. In 1879 Japan annexed the islands and forced the king there to abdicate. China was keen to retain its ancient rights, and pressed Grant to advocate a resolution. Grant insisted that he was both unfamiliar with the matter and a private citizen, but promised to learn about the issue and convey China’s concerns. The precedent for international arbitration his administration established with Great Britain over the Alabama claims stood him in good stead.

An allusion was made to the convention between Great Britain and America on the Alabama question—the arbitration and the settlement of a matter that might have embroiled the two countries. This was explained to His Imperial Highness as a precedent that it would be well to follow now. The Prince was thoroughly familiar with the Alabama negotiations.

General Grant—An arbitration between nations may not satisfy either party at the time. But it satisfies the conscience of the world, and must commend itself more and more as a means of adjusting disputes.

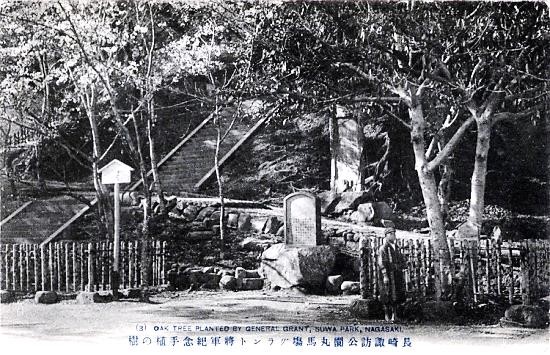

And so we come to Japan, Grant’s final destination before returning to America. The party first touched shore at Nagasaki on June 21, 1879. The next day the general and Mrs. Grant planted trees (a ficus and a camphor tree, respectively) at a memorial garden. Mrs. Grant’s tree did not survive past 1904, but the general’s tree endured the cataclysm of August 9, 1945, when the United States dropped an atomic bomb on that city. Unfortunately, in the aftermath of that horrible day the garden where the trees resided was excavated to build a civil defense shelter. Grant’s peaceful sentiments and the trees themselves were lost, although both the peace and healthy foreign relations were eventually restored.

At the request of the governor, Utsumi Togatsu, Mrs. Grant and I have each planted a tree in the Nagasaki Park. I hope that both trees may prosper, grow large, live long, and in their growth, prosperity and long life be emblematic of the future of Japan.

Grant was greatly impressed by what he discovered in Japan. In taking his leave of the island nation he brought all the perspective he had gained from his earlier travel to bear in praise of Japan’s accomplishments and prospects.

YOUR MAJESTY,--I come to take my leave, and to thank you, the officers of your government, and the people of Japan, for the great hospitality and kindness I have received at the hands of all during my most pleasant visit to this country. I have now been two months in Tokio and the surrounding neighborhood, and two previous weeks in the more southerly part of the country.

It affords me great satisfaction to say that during all this stay and all my visiting I have not witnessed one discourtesy to myself, not a single unpleasant sight. Everywhere there seems to be the greatest contentment among the people, and, while no signs of great industrial wealth exist, no absolute poverty is visible. This is in striking and pleasing contrast with almost every country I have visited.

I leave Japan greatly impressed with the possibilities and probabilities of her future. She has a fertile soil, one half of it not yet cultivated to man’s use; great undeveloped mineral resources, numerous and fine harbors, an extensive seacoast, the surrounding waters abounding in fish of an almost endless variety, and, above all, an industrious, ingenious, contented, and frugal population.

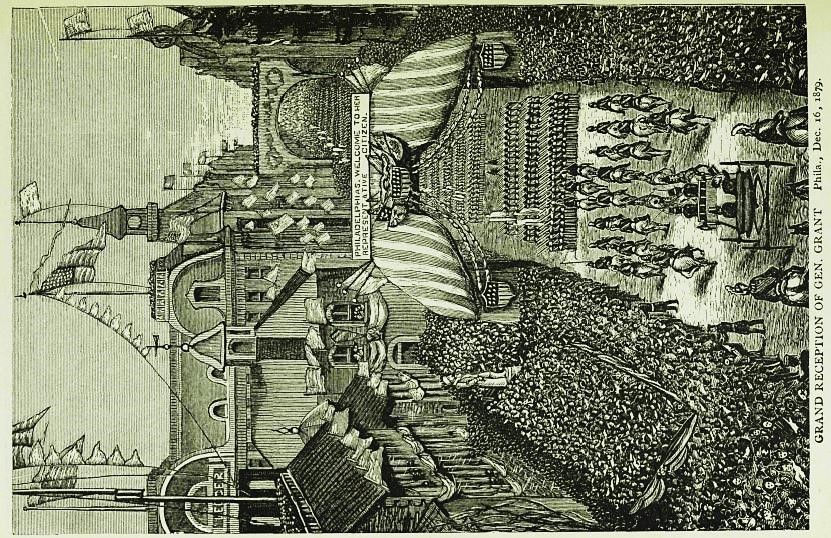

Grant’s party left Japan on the steamship City of Tokio bound for San Francisco where an extravagant reception awaited him, as depicted in the initial illustration of this article in a local paper. It’s a credit to Grant’s sense of duty and honor that he bore the festivities in stride. A lesser man may have crumbled under the weight of such exalted expectations.

The Ex-President’s return to the United States after an absence of over two years, has been the chief topic of public interest in this city for many days past. As a result, extensive preparations for the event had been made. These preparations took the form of a marine display on the bay, in which the yacht fleet and almost every available steam vessel in the harbor was engaged as escort to the Tokio, forming an exhibition such as has never before been witnessed here. Then followed a formal reception by the Mayor at the ferry landing, and a procession through the public streets. The principal streets of the city, especially those on the line of march, had been profusely decorated with bunting and tri-colored streamers. In some parts of the city these decorations formed an almost prefect canopy across the thoroughfare.

The gist of his remarks was conveyed in the following sentiments and observations:

Everywhere, from England to Japan, from Russia to Spain and Portugal, we are understood, our resources highly appreciated, and the skill, energy and intelligence of the citizens recognized. My receptions have been your receptions. They have been everywhere kind, and an acknowledgement that the United States is a nation, a strong, independent and free nation, composed of strong, brave and intelligent people capable of judging of their rights, and ready to maintain them at all hazards.

This is a non-partisan association, but composed of men who are united in a determination that no foe, domestic or foreign, shall interfere between us and the maintenance of our grand, free, and enlightened institutions and the unity of all the states.

Of course, an around-the-world trip can’t truly be complete without the traveler’s returning to the place of departure. Grant’s reception in Philadelphia rivaled that extended to him in San Francisco and marked the real conclusion of his travels. In his last days he settled in upstate New York. He would go on to write that autobiography he had mentioned to the missionaries’ children. It would redeem his family from financial ruin, and serve as his legacy no less than the edifice in Manhattan’s Riverside Park where he and Mrs. Grant are interred.