The Territorial Imperative: Readex’s First Release of the Territorial Papers of the United States

In the early days of the American republic, the territorial imperative that would develop into manifest destiny was more of an optimistic thought experiment than an imperial (or divine) mandate to subdue the wilderness. For the first release of Readex’s Territorial Papers of the United States, let’s examine a few deceptively simple terms and the concepts underlying them, namely Territory, and Paper.

A Territory denotes a specific piece of land over which a consistent level of sovereignty and law is extended. But what did that require, exactly? When surveys were perilous, expensive and imprecise, and even explicit natural boundaries were often contested, the concept of a Territory required magical thinking. Certainly American Indians took that position; the boundaries delineated in treaties and land grants took little account of indigenous traditions, alliances and patterns of settlement. In that much U.S. territories seemed quixotic and arbitrary, foisted upon established societies that could do quite well without legal title, not to mention Indian removal.

![Detail from “The United States 1783-1802. [American History Atlas].” 1803. From the U.S. Congressional Serial Set TPUS 1 1.png](/sites/default/files/blog/TPUS%201%201.png)

Then there was the other magical element of the whole sovereignty enterprise, the transformative mystery of Paper. There’s a Latin proverb, Verba volant, scripta manent: “Spoken words are fleeting; written words remain.” When the promulgation of a law may have taken place hundreds or thousands of miles from any effective entity that could enforce that law, the people required faith in “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” [Hebrews 11:1] to bolster their civic virtue.

The biblical phrase is apt, for Christianity marched alongside the desire for material and temporal dominion. America’s approximation of earthly justice in its territorial possessions was argued over, certified by distant authority as “Law,” and eventually written down on paper and collated in the Territorial Papers as evidence of national intent. Again, English common law would have been a mystery to American Indians who understood European languages poorly if at all, let alone such documents as America’s Constitution, Britain’s Magna Carta or France’s Declaration of the Rights of the Man and of the Citizen.

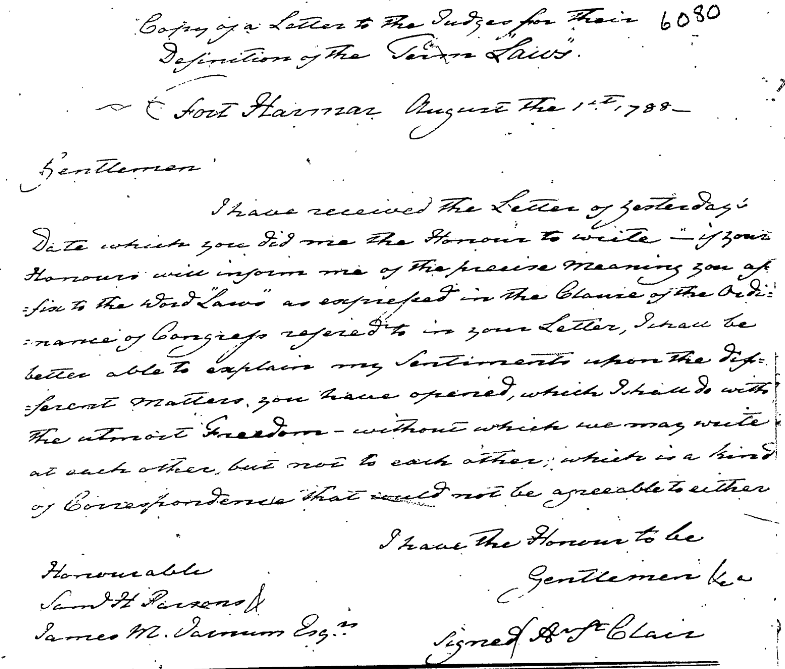

Northwest Territory Governor Arthur St. Clair went so far as to ask his own judges outright what their understanding of “Laws” actually was:

I have received the letter of yesterday’s date which you did me the honor to write—if your honors will inform me of the precise meaning you assign to the word “Laws” as expressed in the clause of the Ordinance of Congress referred to in your letter, I shall be better able to explain my sentiments upon the different matters you have opined, which I shall do with the utmost freedom—without which we may write at each other, but not to each other; which is a kind of correspondence that would not be agreeable to either.

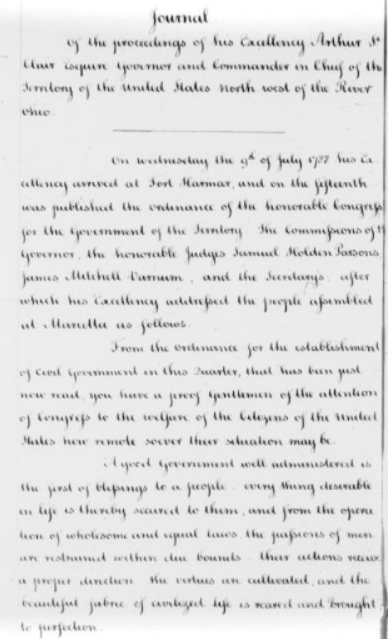

Here’s St. Clair again in 1788 with his desiderata for the administration of those laws:

From the Ordinance for the establishment of civil government in the Quarter, that has been just now read, you have a proof gentlemen of the attention of Congress to the welfare of the citizens of the United States how remote soever their situation may be.

A good government well administered is the first of blessings to a people every thing desirable in life is thereby secured to them, and from the operation of wholesome and equal laws the passions of men are restrained within due bounds, their actions receive a proper direction, their virtues are cultivated, and the beautiful fabric of civilized life is reared and brought to perfection.

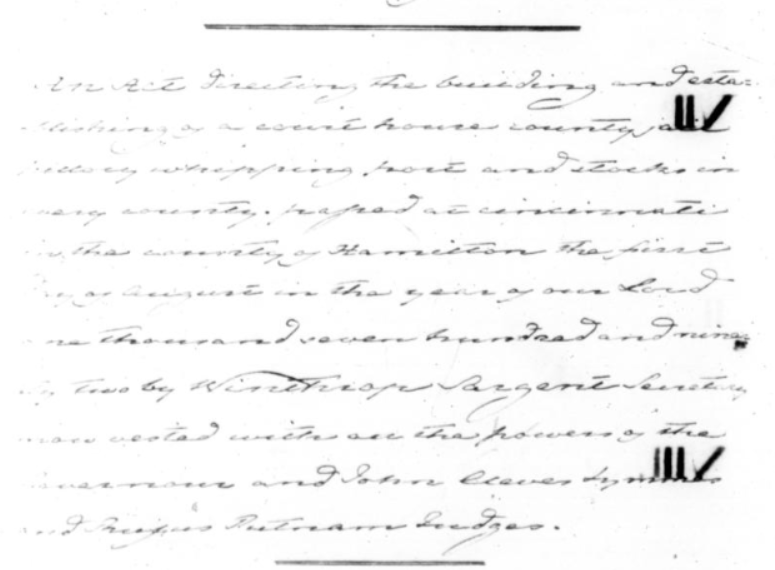

On paper the above passage sounds both lofty and reasonable. Now here’s St. Clair’s secretary, Winthrop Sargent, Acting Governor in the former’s absence, installing the machinery of that justice in 1792:

An Act directing the building and establishing of a court house, county jail, pillory, whipping post, and stocks in every county, passed at Cincinnati in the County of Hamilton the first day of August in the year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred and Ninety Two by Winthrop Sargent, Secretary and vested with the powers of the Governor, and John Cleves Symmes and Rufus Putnam, judges.

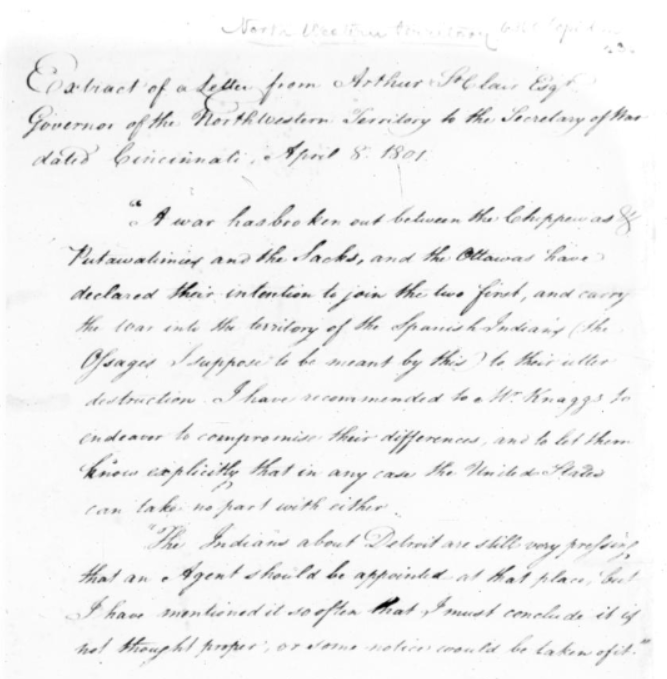

The American Indians were hardly better at avoiding violence; when they weren’t battling the interloping Europeans, they were battling each other:

Extract of a letter from Arthur St. Clair, Esqr, Governor of the Northwestern Territory to the Secretary of War dated Cincinnati April 8, 1801.

A war has broken out between the Chippewas and Patawatamies and the Sauks, and the Ottawas have declared their intention to join the two first, and carry the war into the territory of the Spanish Indians, the Ossages I suppose to be meant by this, to their utter destruction. I have recommended to Mr. Knaggs to endeavor to compromise their differences and to let them know explicitly that in any case the United States can take no part with either.

It’s no wonder then that the Territorial Papers of the United States are filled with death and treachery, with earnest entreaties for those in Washington, D.C., to live up to their promises of support, with urgent calls to “extinguish” Indian land titles, and to circumscribe or annihilate the Indians themselves in the name of a national ideal.

What the reader will find in these pages is rarely abstract or conceptual; these people were literally building the railroad they were riding upon, stopping just long enough to shove the makings of Western civilization out onto the ground before continuing on to the Pacific coast. Vigilantes and fugitives, polygamy, border violence, corruption both real and imagined; the settlers were pushing the limits of the frontier well beyond the boundaries of polite society—and the frontier pushed back.

For more information about Territorial Papers of the United States, including pricing for your institution, please contact Readex Marketing.