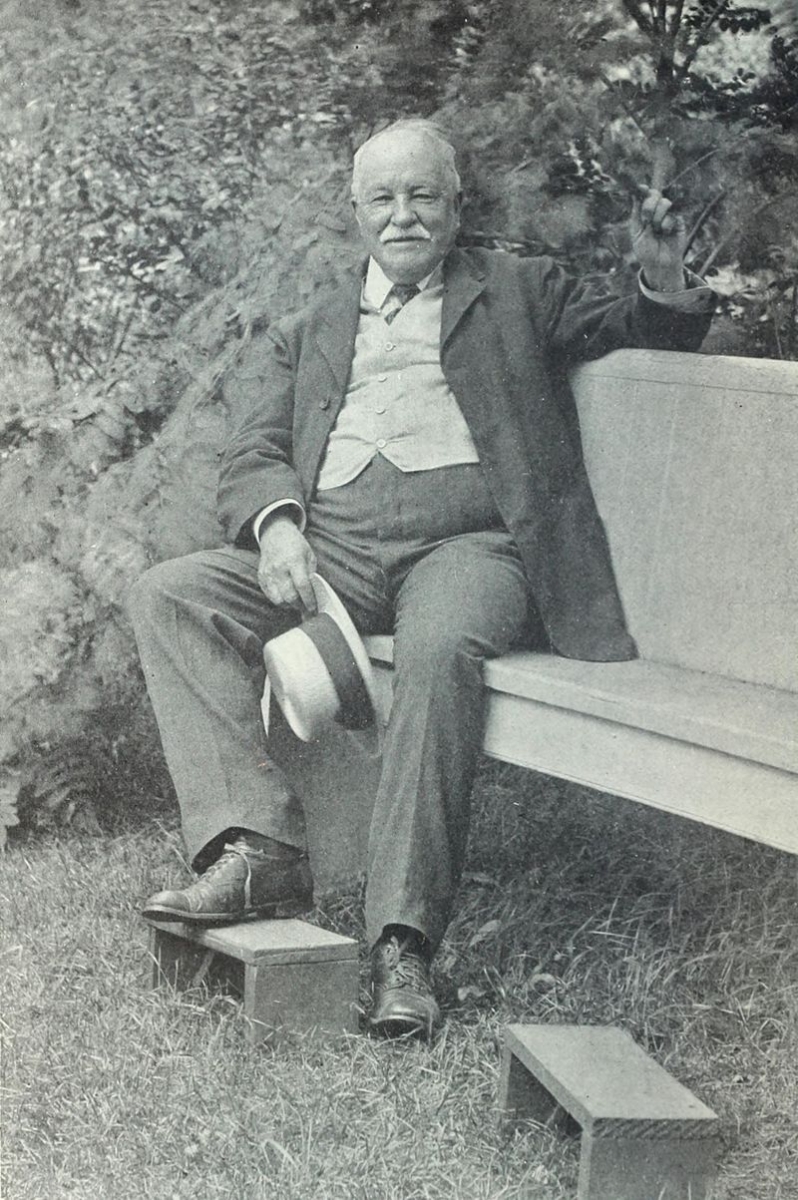

The Theatrical Amuse-Bouches of William Dean Howells, the “Dean of American Letters”

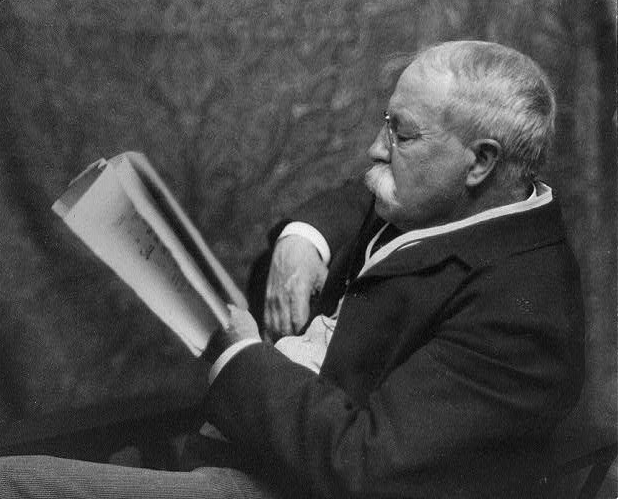

William Dean Howells, author, playwright, critic, was born in Martinsville, Ohio in 1837. During his childhood, Howells moved often around the state as his restless father took a series of jobs as newspaper editor and printer. Young Howells, who would come to be known as “The Dean of American Letters,” assisted his father from an early age acting as the printer’s devil.

He rose rapidly in political and literary circles. Having been elected to the position of clerk in the Ohio House of Representatives, he soon became a major contributor to the “Ohio State Journal” writing short stories, poems, and learning to translate articles from several European languages. His ambition led him to Boston at the age of twenty-three where he met with most of the literary aristocracy of the era. In 1871 he became editor of the “Atlantic Monthly.”

Howells began publishing novels in 1872, but did not achieve fame until ten years later with the release of A Modern Instance. Subsequently, in 1885, his most widely known novel, The Rise and Fall of Silas Lapham, was published. Beginning in 1888, Howells produced a series of novels that came to be known as his “economic novels” and which mirrored his transition to a philosophy of socialism.

Influenced by Leo Tolstoy, Howells is recognized as the first American to infuse his fiction with a realist aesthetic creating novels and stories about prosperous Americans. As he evolved as a writer, his political sensibilities increasingly informed his depictions of the U.S. classes in the latter decades of the 19th century. His plays are mostly farces and feature wealthy people engaged in matters of relatively trivial importance which they magnify to crisis proportions.

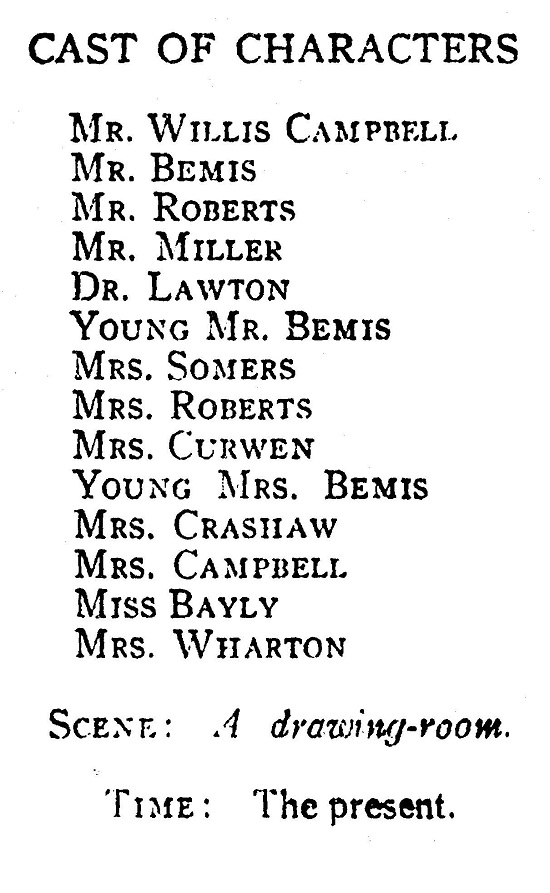

This month’s release of Nineteenth-Century American Drama: Popular Culture and Entertainment includes more than 20 of Howells’ plays which seem to have been written to serve as theatrical amuse-bouches. It is striking that most of them feature the same characters all of whom are clearly wealthy, maintain servants, and have ample time to turn social molehills into mountains. The titles alone are an indication of the prosaic nature of their pampered lives: The Smoking Car, The Sleeping Car, The Albany Depot, and Evening Dress to name just a few.

In each of these farces we encounter Mr. and Mrs. Roberts and Mr. and Mrs. Campbell. Mrs. Roberts is Mr. Campbell’s sister. Episodic appearances are made by Aunt Mary (Mrs. Crashaw) whose niece is Mrs. Roberts, Mr. and Mrs. Bemis, Young Mr. Bemis and wife, Dr. Lawton, and Jane the serving girl.

Each of these people, with the exception of Jane, is prone to excess displays of confused emotion, but none more than Mrs. Roberts. As The Sleeping Car opens we discover her and her Aunt Mary ensconced in a sleeping car and engaged in conversation:

Mrs. Roberts. Do you always take down your back hair, aunty?

Aunt Mary. No never, child; at least not since I had such a fright bout it once, coming on from New York. It’s all well enough to take down your own hair if it is yours; but if it isn’t, your head’s the best place for it. Now, as I buy mine of Madame Pierrot—

Mrs. Roberts. Don’t you wish she wouldn’t advertise it as human hair? It sounds so pokerish—like human flesh, you know.

Aunt Mary. Why, she couldn’t call it inhuman hair, my dear.

[Pokerish is an archaic word meaning eerie. Howells enjoyed displaying his mastery of arcane vocabulary. See “unaneled” in A Previous Engagement or “commensals” in “The Garroters [sic] or “fidge” in The Smoking Car.]

Mrs. Roberts is apprehensive about meeting her brother, Willis Campbell, for the first time in twelve years.

It doesn’t stand to reason that if he’s been out there for twelve years, ever since I was a child, though we’ve corresponded regularly—at least I have—that he could recognize me; not at first glance, you know. He’ll have a full beard; and then I’ve got married, and here’s the baby. Oh, no! he’ll never guess who it is in the world.

She continues to persevere as is her wont. She is obsessively concerned that her husband had already met Mr. Roberts and they don’t like each other, but Aunt Mary posits that “likely they’re sitting down to the unwholesomest [sic] hot supper this instant that the ingenuity of man could invent.”

And with that, Mrs. Roberts is off and running as she expostulates on the probability of the two men coming to an amicable entente. In her paroxysms of trepidatious hope, she natters on disturbing her fellow passengers in their berths. A comical scene ensues when a Californian in an adjacent berth rises to the defense of Mrs. Roberts in light of the increasing grumbling from other berths all devoutly abjuring her to be quiet. He pacifies her and promises her his attention in the morning and soon “nothing is heard but the rhythmical clank of the machinery, with now and then a burst of audible slumber from Mrs. Robert’s aunt Mary.”

At a stop in Worcester Mr. Roberts unexpectedly boards the train and begins to search for his wife with the trying assistance of a porter. At some point the increasingly distraught husband remembers that his wife will have a baby with her. With this information the porter is able to lead Roberts to the right car. Confusion, including a misplaced baby and mistaken identity ensues. Mrs. Roberts waxes and wanes but is ever on the edge of hysteria as she is reunited with her husband. Finally, in the manner of most farces, it all comes right. Willis and his sister and brother-in-law are happily reconciled. Thus, is Willis Campbell ushered into a reoccurring role in many of Howell’s other farces.

The Campbells and the Roberts all appear in The Smoking Car wherein each displays characteristic traits. Mr. Roberts is typically vague and preoccupied. At the top of the play, Howell sets the scene.

In the smoking-car of a suburban train on the Boston and Albany Railroad, in the Albany Depot at Boston. Mr. Edward Roberts is seated, deeply absorbed in a book which he is reading. He has a pile of newspapers and magazines beside him, and he rests an absent hand on them. The seat in front is opened toward him, and he keeps a foot against its edge with the effect of laying claim to it, while a Young Mother, with a child in her arms, enters hastily and looks distractedly about. There is no one else in the car, and after walking its length she returns and addresses herself anxiously to Mr. Roberts.

The Young Mother: “Is this the car for Newton Centre?”

Roberts, starting wildly from his book: “Newton Centre? Why, I don’t know; I presume so; yes. Yes, I think so. I’m going to Newton Centre myself. It is the car for Newton Centre, isn’t it?

The Young Mother: “The brakeman said it was.”

Roberts: “Oh, well, then, it must be. Why”—

And here we go again: The Young Mother, after inquiring if the seat across from Roberts is taken and receiving an ambivalent reply, importunes him to let her leave her baby there for “a minute.” After a great deal of fussing and to-and-froing about the time and the destination of the car, the woman prepares to leave.

By-by, baby! I’ll be right back. I don’t know but I’d better tell her to look after you.

She laughs toward Roberts, as if this were a joke which he must enjoy with her, and vanishes through the door of the car just as Mr. Willis Campbell enters by the door at the other end. He walks down the car toward Roberts, approaching him from the rear.

Upon discovering the baby, Campbell soon suggests that it has been abandoned and congratulates Roberts on having adopted the child. Campbell helps Roberts resolve that he must search for the mother including the suggestion that “you might try leaving it at the package window.” Mrs. Roberts and Mrs. Campbell enter the car and discover Willis who informs that Roberts has a baby and is in search of its mother. After a great deal of confused circumlocution, the group is surprised to see Roberts return with the baby stimulating yet more confusion.

The ladies prevail upon Campbell to take the baby and resume the search. He returns having left the infant with the matron in the ladies’ room. At this point Mrs. Campbell resolves that she and Willis will keep the child and sends her husband to retrieve it. He succeeds. Just as all seems resolved, the young mother returns and explains at tedious length her tribulations. Finally, all is resolved, mother and child are reunited, and the two older couples are able to relax and congratulate themselves.

It is an oddity that Howells seldom includes a list of the dramatis personae, but frequently includes a list of the illustrations which are in themselves unusual for published plays. Completing a brief tour of Howells’ train farces is The Albany Depot which again engages familiar characters in confusion and error while in the depot. And again, Mrs. Roberts cannot help her endless chatter. Upon finding her husband waiting, as promised, in the station she launches:

Mrs. Roberts: “Yes, I know; and I was perfectly sure of it; you’re always so prompt, and I always wonder at it, such an absent-minded creature as you are. But you came near spoiling everything by getting here behind this pillar, and burying yourself in your book that way. If it hadn’t been for my principle of always asking questions, I never should have found you in the world. But just as I was really beginning to despair, the Chorewoman [sic] came by, and I asked her if she had seen any gentleman here lately; and she said there was one now, over here, and I stretched up and saw you. I had such a fright for a moment, not seeing you; for I left my little plush bag with my purse in it at Stearns’s, and I’ve got to hurry right back; though I’m afraid they’ll be shut when I get there, Saturday afternoon is this way; but I’m going to rattle at the front door, and perhaps they’ll come—they always stay, some of them, to put the goods away; and I can tell them I don’t want to buy anything, but left my bag with my purse in it, and I guess they’ll let me in. I want you to keep these things for me, Edward; and I’ll leave my shopping-bag; I shan’t want it anymore. Don’t lose any of them. Better keep them all in your lap here together, and nobody will come and sit on them….I’m almost ready to drop, I’m so tired, and I do believe I should let you go up to Stearns’s for me; but you couldn’t describe the bag so they would recognize it, let alone what was in it, and they wouldn’t give it to you, even if they would let you in to inquire; they’re much more likely to let a lady in than a gentleman. But I shall take a coupe, and tell the driver simply to fly, though there’s plenty of time to go to the ends of the earth and back before the train starts. Only I should like to be here to receive the Campbells, and keep Willis from buying tickets for Amy and himself, and us, too, for that matter; he has that vulgar passion—I don’t know where he’s picked it up—for wanting to pay everybody’s way; and you’d never think of your Hundred-Trip ticket book till it was too late. Do take your book out and hold it in your hand, so you’ll be sure to remember it, as soon as you see Willis. You had better keep saying to yourself. ‘Willis—Hundred-Trip Tickets—Willis—Hundred-Trip Tickets;’ that’s the way I do. Where is the book? I have to remember everything! Do keep your ticket-book in your hand, Edward, till Willis comes.”

Having exhausted the playwright’s store of commas and semi-colons, the lady is ready to expiate on the qualities of the cook she has engaged and admonishing her husband to be on the lookout for her. At long last, she departs only to be replaced by Willis Campbell.

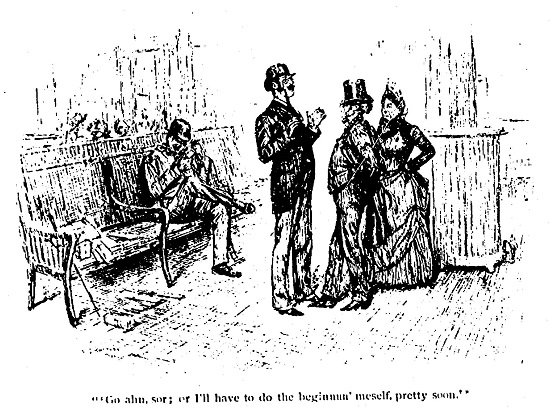

Unsurprisingly, the search for the cook by the brothers-in-law results in consternation and physical peril caused by mistaken identity. Having determined that an older woman conformed to Mrs. Roberts’s description of being “a butterball,” Mr. Roberts approaches her and is met with anger. Soon she returns with her belligerent husband in tow who is described as “a small and wiry Irishman, [who] is a little more vivid for the refreshment he has taken.” There are tense moments at first, but in time the belligerent is able to see the humor in Mrs. Roberts’ having tasked her husband with a nearly impossible task, and they all, including the offended woman, join in on the joke. The couple depart, and the men engage in futile discussion about looking for the cook. It comes to naught.

Mrs. Roberts returns and characteristically natters on and on about her mission. She pauses in her recitation long enough to upbraid the men’s failure to find the cook. Once again, in the manner of most farces, all is happily resolved when the real cook presents herself, and they all bundle off on their train.

These are but three of the many plays by Howells found in this new digital collection. They are depictions of manners presented as farcical. Reflecting the literary accomplishments of the author, they are well written, sometimes witty, and well-structured. Each is a slice of the mundane lives and worries of the privileged classes. Likely, Howells knew these people, and likely, he did not admire them.

For more information about Nineteenth-Century American Drama: Popular Culture and Entertainment, please contact Readex Marketing.