Trilbymania: How a Victorian Novel Became a Viral Sensation in 19th-Century America

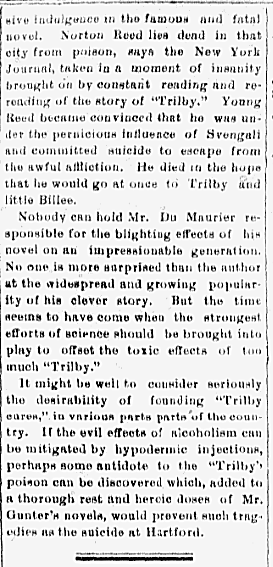

In 1895 at least one death was ascribed to a work of fiction. Its overwhelming influence was described in viral terms before viruses were well understood as biological let alone social phenomena. That book was the bohemian romance Trilby by George du Maurier, a Frenchman living and writing in England. The disorder was called “acute Trilbymania,” which in this case resulted in the suicide of a man in Hartford, Connecticut, who took poison to escape the “awful affliction” of compulsively re-reading the novel.

Like the tragic, titular heroine, the deceased fancied himself under the occult influence of a man who psychically controlled his every action. Trilby O’Ferrall’s fictional nemesis was the mesmerist “Svengali” whose name has become shorthand for a person who exerts just such a malign influence. As the excerpt below indicates, the “widespread and growing popularity” of this novel gave it serious “hoodoo”:

The “Trilby” Hoodoo

The distressing influence of George Du Maurier’s “Trilby” on the human race has taken on a pronounced form of degeneration. The “Trilby” microbe exists and is doing fatal work. It was suspected some time ago that a sure cure for acute Trilbymania was greatly needed, and now a tragedy in Hartford, Conn. emphasizes the demand for something that will overcome the effects of excessive indulgence in the famous and fatal novel. Norton Reed lies dead in that city from poison, says the New York Journal, taken in a moment of insanity brought on by constant reading and re-reading of the story of “Trilby.” Young Reed became convinced that he was under the pernicious influence of Svengali and committed suicide to escape the awful affliction.

In 1894 du Maurier was already a successful artist and illustrator for the satirical British magazine Punch and hardly needed another claim to fame. He began writing when his failing eyesight made drawing more difficult. Trilby was his second major work. He offered its plot to Henry James who insisted that du Maurier should write the story himself. It first appeared serially in Harper’s Monthly and was then published as a book. Du Maurier wrote it in six weeks—nine weeks counting the drawings he did for it.

The characters and milieu were loosely based on the author’s experiences in the colorful and eclectic Quartier Latin of Paris, home to a number of academic institutions and the students who attended them.

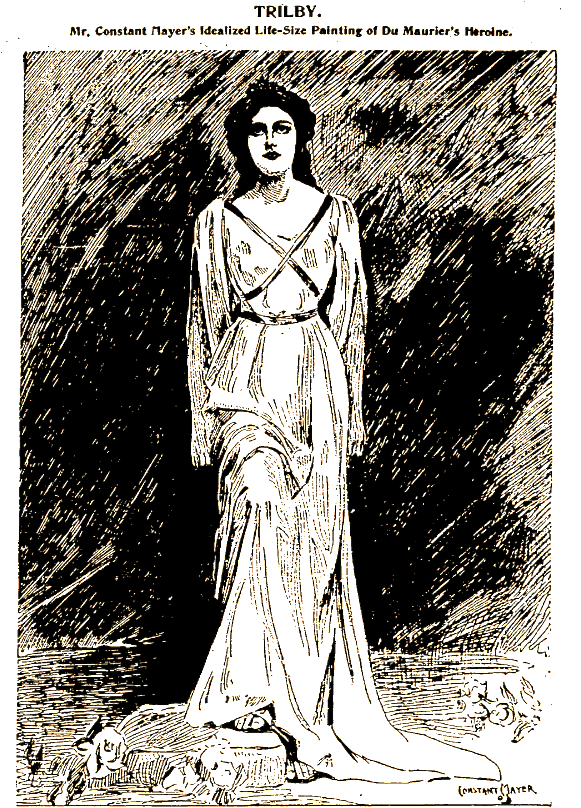

In the novel three young English men and aspiring artists—“the Laird, Taffy and Little Billee”—meet Jewish musician Svengali and Trilby, a Scotch-Irish orphan, artist’s model and laundress. Trilby is a striking, ebullient, free-spirited young woman who does not always live in a manner deemed acceptable by polite society of the day, for example by posing nude or, as du Maurier wrote, in “the altogether.”

The men in the novel are simultaneously enticed and threatened by Trilby’s vitality and frank sexuality. They fall in love with her, notably Little Billee who proposes marriage to her which she reluctantly accepts. But it was not to be.

Little Billee’s Victorian morality causes Trilby to doubt herself, and his disapproving mother convinces Trilby to break-off their engagement. Trilby leaves Paris and under Svengali’s hypnotic will she becomes famous as the opera diva “La Svengali,” although she is herself tone-deaf. She eventually encounters Little Billee again, who has achieved fame as a painter. When Svengali dies Trilby loses her musical ability and dies shortly thereafter.

In 1894 a reviewer of the novel quoted du Maurier’s description of Trilby’s singing voice when she was under Svengali’s spell:

But her voice was so immense in its softness, richness, freshness, that it seemed to be pouring itself out from all around; its intonation absolutely, mathematically pure, and the seduction, the novelty of it, the strangely sympathetic quality! How can one describe the quality of a peach or a nectarine to those who have only known apples?

The sensation the novel caused could likewise have been described in terms of “seduction.” Readers were enthralled by Trilby from head to toe:

Trilby matinees are the society rage, and it is said that Du Maurier has received thousands of photographs from young ladies who want to know if they do not resemble the heroine of his charming story. While these young ladies are posing as Trilby and having their photographs taken in Trilby gowns and Trilby poses, do they remember that Trilby’s throne was a footstool, and that the one feature which brought Du Maurier and Little Billee, the Laird and Taffy to her feet as worshipers was in fact her feet?

Du Maurier described Trilby’s feet as her best feature, which led to the popularity of Trilby footwear and the interpretation of character from the shape of one’s feet.

Feet encased in patent leathers, with Picadilly toes, do not get much of a chance to show anything about the character of their owner. After they have been kept in unyielding, enamelled coffins for a few years there isn’t a really flesh and blood foot there any more. There’s a calloused, bumpy, gnarled and warped sort of a thing there, which shows no characteristics, except, perhaps, lack of common sense in the owner. But there are men and women whose feet have the semblance of the shape they had when they romped around the nurseries, before the days of narrow toes and French heels.

This Trilby craze has done much to induce us to treat our feet decently and respectably. Many a young woman who has pondered over Du Maurier's description of the most beautiful foot in all Paris has had the courage to order shoes which were large enough for her, and some even had the temerity to appear in footgear almost as loose as the slippers in which Trilby paid her first visit to the “Laird” and Little Billy.

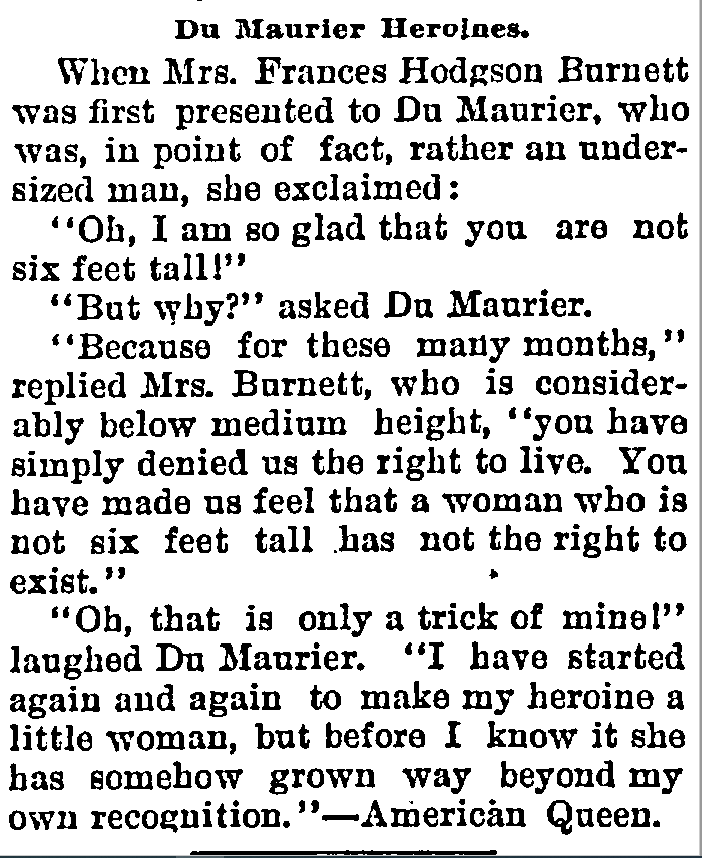

Since Trilby was tall, women readers obsessed that they did not measure up to du Maurier’s statuesque heroine. Even Frances Hodgson Burnett, author of popular children’s books such as Little Lord Fauntleroy and The Secret Garden, was relieved to find that du Maurier was himself physically unimposing:

When Mrs. Frances Hodgson Burnett was first presented to Du Maurier, who was, in point of fact, rather an undersized man, she exclaimed:

“Oh, I am so glad that you are not six feet tall!”

“But why?” asked Du Maurier.

“Because for these many months,” replied Mrs. Burnett, who is considerably below medium height, “you have simply denied us the right to live. You have made us feel that a woman who is not six feet tall has not the right to exist.”

“Oh, that is only a little trick of mine!” laughed Du Maurier. “I have started again and again to make my heroine a little woman, but before I know it she has somehow gotten way beyond my own recognition.”

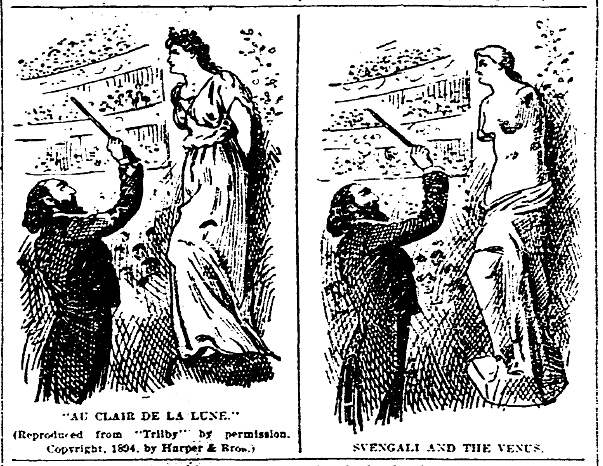

Speaking of statuesque characters, a lively discussion arose as to whether du Maurier had modeled Trilby upon the Venus de Milo, on display in Paris at the Louvre Museum. The illustration below compares one of Du Maurier’s original drawings with a rendering of the Venus de Milo in the same setting.

Despite Trilby’s depiction as an ingénue and a victim of circumstance, readers still needed the author’s explicit reassurance that his charming protagonist was morally unsullied by her association with Svengali.

Frederick W. McCully, a resident of Newark, in business with his father, F.K. McCully, the Paterson banker, wrote to George du Maurier on a disputed point about “Trilby,” and has received the following autograph letter:

New Grove House,

Hempstead Heath, October 31, ’94.

Dear Sir: In answer to your letter of September 24, I beg to say that you are right about “Trilby.” When free from mesmeric influence she lived with him as his daughter and was quite innocent of any other relation. In haste. Yours very truly,

G. DU MAURIER.

Age was no limit to the devotion of Trilby’s admirers. Seven hundred elderly women in the Kings County (New York) Almshouse were unanimous in their admiration for the novel and its heroine.

The very important question, “When does a woman cease to feel or to sympathize with the emotion called love?” of all places on this mundane sphere, has been answered in the Kings County Almshouse. The answer is, “Not until she dies, or until she lives to be more than one hundred years old.” The oldest woman in the almshouse, Mary Ushers, claims to be a hundred.

The answer is the more interesting, because it was elicited by “Trilby.” Never has Du Maurier received a more sincere compliment.

Seven hundred friendless old women are supported in the almshouse, which they enthusiastically style “the county building.” Mrs. Quay, the matron, like everybody else, read “Trilby.” She gave the book to her favorite old woman. She read it, and passed it to her dearest friend. Now a “Trilby” epidemic is raging in the almshouse.

Mary Eagan told Mrs. Quay that she would never die in peace until she read “Trilby.” Mary Eagan is a sprightly woman who does not know just how old she is. She insists, however, that she was digging potatoes in the field and eighteen years old, when her father went to her, greatly excited and cheering, and told her that Bonaparte had been thrashed at Waterloo. That battle was fought in June, 1815. So Mary Eagan is about ninety-eight years old.

A Trilby “cult” developed:

The marvel of the book trade nowadays is the great and increasing sale of “Trilby.” It is not too much to say that Mr. Du Maurier’s charming story has proved itself one of the most popular works of fiction of our time. Though less than two months have gone since the novel appeared in book form, we are credibly told that nearly one hundred thousand copies of it have been sold, a record which we believe is unsurpassed.

Mr. Du Maurier, before eminent, now finds himself famous, and we dare say that he goes home each night to those pretty daughters of his, with whose portraits admirers of his drawings are familiar, and tells them stories of the prodigious sale of his book, much as Macaulay used to write daily to his sister Hannah how his history was going by scores of thousands, and his own name was thenceforward historical.

It should be remembered that the figures of the sale represent far more than that number of actual readers; and we are not surprised to learn that in communities more or less isolated, “Trilby” has created much the same fury that the single copy of “Clarissa” did when it arrived at Jamaica, and was borrowed and fought for and cried over by the officers and soldiers of the entire English garrison, and their wives. There are all the signs of a real “Trilby” cult.

The novel Clarissa that was compared to Trilby was a 1748 story by Samuel Richardson which featured another besieged heroine. Like Trilby, Clarissa lost her honor and life at the hands of a perfidious man. Clarissa’s respite from the unwanted attention of Lovelace, portrayed below, did not last; she was eventually kidnapped, drugged, and raped.

Richardson’s 1740 Pamela was similarly sensational in its time and is regarded as the first English novel. Unlike Clarissa or Trilby, Pamela finally married well despite her travails and social deficiencies. Trilby, however, was reimagined as the plaything of Death in order to advertise patent medicine:

Nearly everyone has read Du Maurier’s story of “Trilby” and how she lived under the hypnotic spell of “Svengali” and then broke the spell only to die. There are tens of thousands of women to-day living under the spell of a “Svengali” from which they will only awaken to die. Their “Svengali” is ill-health. The woman who neglects to take care of her health in a womanly way is living under a spell of false security from which she may only awaken when it is time to die.

The Trilby/Svengali relationship has had many cognates, among them the case of Anna Rivière, the daughter of a French musician, who married English composer Sir Henry Bishop. Lady Bishop already had a career as a soprano when around 1839 she fell under the sway of Nicholas Charles Bochsa, a French harpist and composer. He developed Bishop’s voice to such an extent that she left her husband and toured the world with Bochsa. This relationship was said to have informed du Maurier’s characterization of Trilby.

Bochsa was a tall, portly, handsome man, with something of the cast of countenance attributed to Svengali, but, of course, not so accentuated, and his genius was precisely of that wild Bohemian nature that so markedly appears in all the musical doings of Trilby’s “maestro.”

The mysterious influence exercised over Mme. Bishop by Bochsa, was matter of common report and comment in the musical worlds of New York, London, Melbourne and Sydney. Hypnotism had not been invented in those days, so that the gossips attributed the control exercised by the man over the girl to the power of love. But Du Maurier, as a friend of the family and protégé of Sir Henry Bishop, knew better, and always said that, whatever the influence was it was spiritual and not carnal. To the end of her life, as may well be judged from the novel, Du Maurier was Anna Bishop’s friend and champion. Many a time he has defended her at the meetings of artists at the “Cheshire Cheese,” the “Cock,” and Evan’s tavern. No one was better acquainted with the true inwardness of the case, as indeed he has proved by his wonderful description of Trilby’s career as a prima donna.

The character of Svengali has been noted for its anti-Semitic stereotypes which were played for comic effect in stage adaptations of Trilby. One such play, Trilby: A Burlesque of the Play of the Same Title (1899) is available as a promptbook in Readex’s Nineteenth-Century American Drama collection. The dialogue on page seven leaves no doubt that Svengali was not just a villain; he was a Jewish villain. In this production Jocko is a trained monkey standing in for the novel’s Gecko, a Polish violinist.

BILLEE.

Let her go Svengaliger!

Svengali and Jocko play a duet. Jocko stands on piano. Taffy pours out drink. Jocko stops playing grabs the drink and jumps back to piano.

SVENGALI.

How do you like it?

(Piano continues to play.)

Dat’ll do out there. I’m through.

TRILBY.

It gives me a headache.

SVENGALI.

I can cure it. Look Svengali in the eye.

TRILBY.

What a strange light in your eyes!

BILLEE.

That’s Israelite.

(Svengali makes passes at Trilby.)

SVENGALI.

See! She will not speak. Ask her.

LAIRD.

Speak, Trilby.

TRILBY.

I can’t.

SVENGALI.

I will release her.

TRILBY.

(Rising.)

The headache is gone!

LAIRD.

No wonder. Whatever he lays his hands on is gone.

TAFFY.

(Slapping Svengali on back.)

Let up Svengali, take Ole Bull and get out. Time is fleeting and there are other people in the cast.

SVENGALI.

Very goot, I go, but someday you will be glad to know Svengali. For the world will recognize in me the greatest piano blayer the world has ever seen…

One man who admired the character of Svengali was the famous French painter Théobald Chartan, whose sketch of Trilby appears earlier in this article. That sketch and a companion piece of Svengali were executed at the request of a journalist interviewing Chartran for the New York Mail and Express in 1895. Like du Maurier, Chartran had spent time in Paris’ Quartier Latin, and recognized the “more or less regular types” of person encountered there in du Maurier’s novel.

Chartran confessed to finding Svengali the strongest and most interesting male character despite the Jewish stereotypes employed to cast him as a villain,

But Svengali, he is really a strong and attention-compelling figure. Svengali, with his dominating ability, his far-reaching ambitions and his unswerving determination to succeed. A bad man, I admit; but you must concede that he at least possessed qualities which command alike success and respect. My taste may be depraved, but Svengali for me has a strong attraction.

Inasmuch as the character “Trilby” was co-opted and destroyed by painters and a pianist, du Maurier held that the success of Trilby contributed to his own demise. In an interview during the height of “Trilbymania,” the author was wistful for the peace and quiet of his former life.

“How about the offers to lecture in America?” I asked. “When are you going to visit your many friends on the other side of the Atlantic?”

“I have had a great many advantageous offers, both to lecture and read, in the United States,” was the answer. “But I am growing to dislike all rush and worry. I prefer being more quiet. I enjoy, too much, my nook here,” said the artist, glancing [lovingly] from his window in the direction of Hampstead heath.

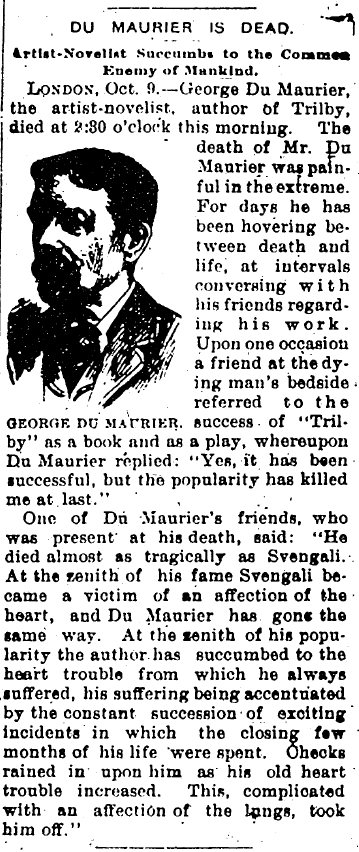

During du Maurier’s final illness in 1896 he was more explicit in his self-diagnosis:

Upon one occasion a friend at the dying man’s bedside referred to the success of “Trilby” as a book and as a play, whereupon Du Maurier replied, “Yes, it has been successful, but the popularity has killed me at last.”

One of Du Maurier’s friends, who was present at his death, said: “He died almost as tragically as Svengali. At the zenith of his fame Svengali became a victim of an affection of the heart, and Du Maurier has gone the same way. At the zenith of his popularity the author has succumbed to the heart trouble from which he always suffered, his suffering being accentuated by the constant succession of exciting incidents in which the closing few months of his life were spent. Checks rained in upon him as his old heart trouble increased. This, complicated with an affection of the lungs, took him off.”

One of his own drawings for Punch foreshadowed his decline and both the irony and grim humor of it. The figure on the left even resembles du Maurier.

THINGS ONE WOULD HAVE EXPRESSED DIFFERENTLY

“How are you, old chap? Are you keeping strong?”

“No, only just managing to keep out of the grave.”

“Oh, I’m sorry to hear that.” –Du Maurier in Punch.

Although du Maurier’s novel has not aged as well as his contemporaries speculated it would, its heroine’s name has entered the vernacular as the “Trilby” hat, a narrow-brimmed fedora that became an enduring fashion statement when it was worn by an actress in an early stage adaptation of the novel.

Readex’s collections are always in fashion. For more information about bringing them to your institution, please contact Readex.