Unreconstructed: The Rise of Rifle Clubs—White and Black—during Racial Violence in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

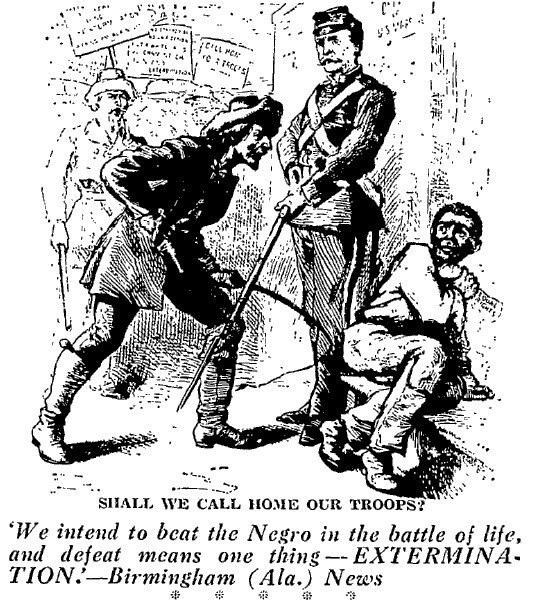

The word “club” has divergent associations: on the one hand it relates to a weapon, on the other to a group of like-minded individuals who gather regularly for a specific purpose. Following the American Civil War both usages coalesced in “rifle clubs,” consisting generally of White people who used firearms and terrorism to bolster Democratic Party control and suppress African American civil rights.

Under such severe discipline, African Americans learned the political uses of firearms. During the 1960s the Deacons for Defense and Justice, the Black Panthers, and the National Negro Rifle Association adopted the tools and organizational structures of their oppressors to protect themselves. The Second Amendment makes no distinctions as to race. Yet Black leaders such as Malcolm X, Huey Newton, Robert and Mabel Williams, Edward Crawford and others were persecuted and prosecuted for asserting their Second Amendment rights of self-defense against racially-motivated attacks when lawful nonviolent avenues for the protection of their civil rights were consistently denied them.

The militant aspects of the American civil rights movement have been largely glossed over in favor of the more socially acceptable narrative that unalloyed nonviolent resistance won the day. But even proponents of nonviolence such as Martin Luther King, Jr., sometimes found it necessary to employ bodyguards to shield them from assault. King himself applied for and was denied a permit to carry a handgun in 1956 after his Montgomery, Alabama, house was bombed. During the 1965 march from Montgomery to Selma, King employed veteran Tuskegee Airman Dabney Montgomery as a bodyguard. Rosa Parks grew up in a house with guns readily available for self-defense, and kept them in her home as an adult.

Black Life in America, a comprehensive new digital resource, is a powerful tool with which to trace the unequal distribution of the Second Amendment rights of American citizens to bear arms for self-defense. The historical record is clear that gun control measures have been unjustly applied along racial lines. It’s revealing to trace the extent to which armed resistance backstopped nonviolent protest, and to consider how current social movements have evolved into leaderless, borderless, organic expressions of dissent.

In the image above, the Black Panthers are bearing arms in protest of House Bill No. 123, a gun control measure specifically intended to prevent them from openly carrying weapons in Washington State. Their demonstration was in fact nonviolent; the guns were unloaded, and the demonstrators left quietly after thirty minutes once their leaders had by invitation addressed the State Senate. Behind closed doors the Panthers made their point rhetorically and were invited back. Outside on the steps they made their point symbolically—effectively at gun-point—and the legislators were glad to see them go. Despite the Panthers’ political theater the 1969 bill passed quickly. Several years earlier then-Governor Ronald Reagan passed a similar measure, the Mulford Act, in California. Where did this armed advocacy come from?

The Rise of the Rifle Clubs

During the 1876 U.S. presidential election, voter intimidation and fraud were not merely hypothetical; on behalf of both Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden, election tampering was an accomplished fact. On the Republican side, then the party of Lincoln styled as “radical” in the South, charges were leveled in New Orleans of “a wholesale erasure of white votes” through the artifice of sending an advertisement for a fictional sewing machine company to a targeted list of White Democratic Party voters. If those persons were not readily found at the addresses from which they formerly registered, they were stricken from the rolls of eligible voters. The Courier-Journal of Louisville, Kentucky, gives us a glimpse into the machinations exercised for and against the election of Rutherford B. Hayes.

Republican officials have decided to stretch ropes around the various polls on election day, and fill the space inside, thirty feet in diameter, with armed deputy U.S. marshals, constables, and State militia. Seven companies of United States infantry arrived last night. Efforts will be made by Radical supervisors of registration to get the registration lists in the custom-house to-night, when they will make a wholesale erasure of white votes on the sewing-machine circular affidavits.

In the Superior Criminal Court, presided over by a Republican judge, Moore, Radical supervisor of registration, indicted for erasing names from his lists, was discharged this morning. In view of the fact, the Radical paper here insinuates that two white independent military organizations will be used by Democrats on election day. Both these organizations will immediately tender their services to Gen. Auger [i.e., T.H. Ruger]. It is known now that the Radicals have distributed from five to ten thousand Winchester rifles to negro rifle clubs throughout the State.

Ah, the rifle clubs. What were they, really? Militias? Vigilantes? Thugs? At various times their members performed all those roles. Following the Civil War, both Union and Confederate veterans often served in segregated companies of militia. In the Southern states, when politics or social expediency overwhelmed the acceptance or influence of the federal government, the result was the rifle clubs—paramilitary organizations both Black and White that carried on the American Civil War by proxy when federal authority broke down.

The Compromise of 1877 resolved the contested presidential election of 1876 in favor of Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, but at a price: federal troops would be withdrawn from Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida, and the Republican project of Reconstruction would be abandoned.

In the period between the end of the Civil War and 1877, Black companies of militia were formed in the South. Although they were sanctioned by the federal government, they were nonetheless tenuous in the sense that they were imposed by and dependent upon the occupying force of the U.S. Army. They were never sustainable as a tactical force. Case in point: in July 1876 during the Hamburg Massacre in South Carolina, a company of Black militia was attacked by “Red Shirt” rifle club members when the militia used a public road for parade practice. The Red Shirts were militarized Democratic partisans who adopted the habit of wearing red shirts to mock the Republican campaign trope of “waving the bloody shirt” to shame Confederate loyalists. Six Blacks and one White were killed.

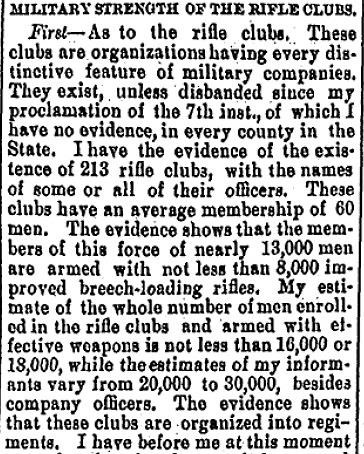

White Southern Democrats smarting over the defeat of the Confederacy viewed armed and trained Blacks as an existential threat to the status quo ante and reacted by forming their own quasi-official military companies. South Carolina Governor Daniel Henry Chamberlain, a Republican, gave an account of the White rifle clubs in a letter to the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (West Virginia) published on October 28, 1876.

First—As to the rifle clubs. These clubs are organizations having every distinctive feature of military companies. They exist, unless disbanded since my proclamation of the 7th inst., of which I have no evidence, in every county in the State. I have the evidence of the existence of 213 rifle clubs, with the names of some or all of their officers. These clubs have an average membership of 60 men. The evidence shows that the members of this force of nearly 13,000 men are armed with not less than 8,000 improved breech-loading rifles. My estimate of the whole number of men enrolled in the rifle clubs and armed with effective weapons is not less than 16,000 or 18,000, while the estimates of my informants vary from 20,000 to 30,000, besides company officers. The evidence shows that these clubs are organized into regiments.

It must have been a strange experience for Blacks and Republicans to find themselves once again fighting for their lives a decade after emancipation and victory. The excerpt above was actually written in the context of describing the 1876 Ellenton Massacre in South Carolina near Augusta, Georgia. What follows is just a portion of Governor Chamberlain’s account of that tragedy:

During the 17th [of September 1876] a large part of the rifle clubs moved off from Rouse’s Bridge to Union Bridge and Ellenton, on the Port Royal Railroad, and during the day shot and killed a considerable number of colored men, probably as many as twelve. At one cabin they found six colored men who had crawled out of the swamp to get something to eat. The rifle clubs surprised them, killed two of them in the yard, two more while running to the swamp, and wounded the remaining two.

Early on the morning of the 18th the rifle clubs appeared in great force on the Port Royal Railroad, having been reinforced by white men from Augusta. They moved up and down the railroad, killing all colored men whom they chanced to find. Among their victims was an old man of 90 years, and a harmless deaf and dumb boy.

The Ellenton Massacre was only curtailed by the intervention of the Eighteenth United States Infantry. About 100 Black citizens were killed and at least that many more were saved at the last possible moment.

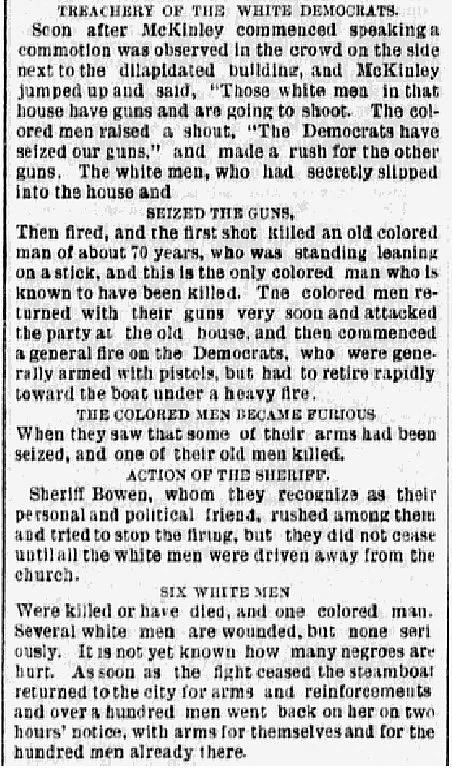

Not every African American capitulated to the reinstatement of White power, however. A month after the Ellenton Massacre a group of armed Black Republicans put an outnumbered and less heavily armed group of White Democrats to flight in Cainhoy on the outskirts of Charleston, South Carolina. The Cainhoy Riot grew out of the practice of White Democratic rifle clubs disrupting Republican political rallies and demanding equal speaking time. Fearing bloodshed, the local leaders of the two parties met and agreed that their supporters would thenceforward attend unarmed, which in the custom of the day meant they would carry only pistols.

This was just a month after the Ellenton Massacre, and the Republicans were understandably wary of surrendering their arms. Nonetheless when attending a Democratic meeting in Cainhoy on October 16, 1876, they agreed to deposit their long guns in two stacks a short distance from the speaker’s stand. A Democrat spoke first, and then Republican W.J. McKinley, a Black man, stepped up to speak. U.S. Marshal for South Carolina R.M. Wallace described what happened next.

Soon after McKinley commenced speaking a commotion was observed in the crowd on the side next to the dilapidated building, and McKinley jumped up and said, “Those white men in that house have guns and are going to shoot.” The colored men raised a shout, “The Democrats have seized our guns,” and made a rush for the other guns. The white men, who had secretly slipped into the house and seized the guns, then fired, and the first shot killed an old colored man of about 70 years, who was standing leaning on a stick, and this is the only colored man who is known to have been killed. The colored men returned with their guns very soon and attacked the party at the old house and then commenced a general fire on the Democrats, who were generally armed with pistols, but had to retire rapidly toward the boat under a heavy fire.

Six White men were killed and several others wounded. But the Cainhoy Riot would be an isolated victory for Blacks and Republicans. Life would become far worse for them and their supporters.

In 1878 the Posse Comitatus Act effectively barred the use of federal troops for law enforcement purposes; the state militias were given that responsibility. Recall that state governments in the South were deeply invested in maintaining White segregationist political and social structures. After 1878 the White rifle clubs could with impunity inflict their version of retributive justice upon Republicans and Blacks as Reconstruction was dismantled. The Jim Crow era had begun.

Thankfully, not all protests were violent. In 1891, lawyer and educator David Augustus Straker cited the rifle clubs as he gave voice to the frustration of many in the Black community:

Has not usurpation raised its standard in the South and tramped upon the liberties of thousands of voters, and does not the national government behold the encroachments, while no succor it is said can be constitutionally afforded? Never was prophecy so completely fulfilled, and yet the danger seems not to be fully appreciated. It is said to leave the so called Southern problem of protection to the voter, but which is really a national obligation and duty to the South, and it will regulate its own internal affairs. How has the South kept oft repeated promises in this respect since 1876?

The olive branch it has offered has been the shot gun and the rifle club, Ku Klux Klans and ballot-box stuffing. What a shame to the descendants of the Puritan, the Huguenot and the Chevalier. With what degree of pride will the children of the oppressors of the Negro of the South read the pages of a future history which recounts their bloody deeds and oppression towards a weak and defenseless race of people?

Jumping forward to 1925 we find the case of Dr. Ossian Sweet, a surgeon who had just moved his family into a Detroit neighborhood reserved for Whites when he found a mob in his front yard. The Sweets had already received threats. A police guard posted nearby appeared unwilling to intervene. What to do? The Sweets were prepared to fight back. When the mob began throwing stones at the house several of those inside opened fire, killing one White man and wounding another. Eleven family members and friends were arrested and tried for murder. Prominent Chicago attorney Clarence Darrow led their defense and won mistrials and acquittals.

Thirty-five years later, racially-motivated attacks against African Americans were still so prevalent that Robert F. Williams of Monroe, North Carolina, U.S. Marine veteran and president of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) began a National Rifle Association-sanctioned rifle club in his community in response to Ku Klux Klan threats. Klan members were upset over Williams’ efforts to integrate the municipal library and to build a swimming pool for Blacks comparable to the existing Whites-only pool. Like the Sweets, Williams decided to fight back. Like those veterans of the American Civil War, he was trained to do so.

Robert F. Williams, a Monroe, NC, Negro leader, says he is collecting rifles for two reasons: To form a rifle club for sport and for an “armament race with the white people of Monroe.”

Williams, an avowed admirer of Cuban Dictator Fidel Castro, declined to say how many members he has in his rifle club, but he said the group has about 100 weapons, mostly foreign rifles.

“I keep an armed guard on my house at night,” he said yesterday. “If anyone attacks my house, the City of Monroe is going to see a blood bath.”

Among other things, Williams’ club, the Black Guard, protected the nonviolent Freedom Riders when those activists came to Monroe in 1961. Shortly thereafter Williams would be suspended from his position with the NAACP when he advocated meeting “violence with violence.” He and his wife would subsequently flee the country when they were falsely charged with kidnapping a White couple whom they had sheltered in their home. The out-of-town couple had gotten lost in the neighborhood and was threatened by angry mobs before the Williams rescued them. Charges against Robert Williams would later be dropped when he and his wife returned to the United States in 1969.

In 1964 Malcom X, formerly Malcolm Little, would follow Williams’ lead in proposing the formation of Black rifle clubs. Less than a year after issuing this call to arms, Malcolm X would be dead from gunshot wounds attributed to assassins from the Nation of Islam with which he had recently broken over alleged moral lapses of its leader, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad.

National civil rights leaders were shocked almost to disbelief today by the advice of militant Negro leader Malcolm X that Negroes should form “rifle clubs.”

Most said they agreed that the break-away leader of the Black Muslim movement could endanger civil rights progress and domestic peace with his urging that Negroes begin to “fight back in self defense.”

“I can’t believe he’s serious,” said James Farmer, national director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). He said that to unleash such violence could be “ultimately suicidal.”

Malcolm Thursday opened formally his announced campaign to organize a politically oriented black-nationalist movement. “There will be more violence than ever this year,” he said at a news conference in a hotel here.

“White people will be shocked when they discover that the passive little Negro they had known turns out to be a roaring lion. The whites had better understand this while there is still time,” he said.

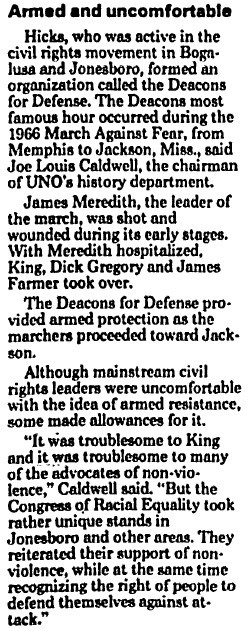

The persistent official disavowals of armed self-defense by Black civil rights leaders did not quite align with their actual practices. For example, there’s the 1966 “March against Fear” from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi. Its leader, James Meredith, a law student at Columbia University, was shot twice with a shotgun at mile 27 of the 220-mile route. The militant and armed Deacons for Defense and Justice were called in to provide security.

[Robert] Hicks, who was active in the civil rights movement in Bogalusa and Jonesboro, formed an organization called the Deacons for Defense. The Deacons’ most famous hour occurred during the March Against Fear, from Memphis to Jackson, Miss., said Joe Louis Caldwell, the chairman of UNO’s history department.

James Meredith, the leader of the march, was shot and wounded during its early stages. With Meredith hospitalized, [Martin Luther] King, Dick Gregory and James Farmer took over.

The Deacons for Defense provided armed protection as the marchers proceeded toward Jackson.

Although mainstream civil rights leaders were uncomfortable with the idea of armed resistance, some made allowances for it.

“It was troublesome to King and it was troublesome to many of the advocates of non-violence,” Caldwell said. “But the Congress of Racial Equality took rather unique stands in Jonesboro and other areas. They reiterated their support of non-violence, while at the same time recognizing the right of people to defend themselves against attack.”

Stokely Carmichael, leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), was also at the March against Fear. As one might gather from SNCC’s name Carmichael started out adhering to nonviolence. He had previously served as a field organizer for SNCC in Lowndes County, Alabama, where he designed the political logo that was later adopted by the Black Panthers. As an indication of his growing frustration with the nonviolent approach to activism, in a speech during the 1966 march Carmichael weaponized the phrase, “Black Power.” By August 1967 David Gillespie, associate editor of the Charlotte Observer (NC) wrote, “Stokely Declares War:”

“We have no alternative but to use aggressive armed violence in order to own the land, houses and stores inside our communities and to control the politics of those communities,” said the former head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

But Does It Explode?

We’ve traced the racial aspects of armed self-defense from Reconstruction, through the Jim Crow era, and well into the Civil Rights Movement. We’ve also seen that many of the leading activists of that movement who espoused nonviolence as a defensible strategy had a conflicted relationship with armed resistance to oppression. Inasmuch as African Americans suffered many of the predations and indignities of fugitive slaves throughout the greater part of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a forceful, patriotic Frederick Douglass quotation seems apt:

THE TRUE REMEDY FOR THE FUGITIVE SLAVE BILL.—A good revolver, a steady hand, and a determination to shoot down any man attempting to kidnap. Let every colored man make up his mind to this, and live by it, and if needs be, die by it. This will put an end to kidnapping and to slaveholding, too. We blush to our very soul when we are told that a negro is so mean and cowardly that he prefers to live under the slaveholder’s whip—to the loss of life for liberty. Oh! That we had a little more of the manly indifference to death, which characterized the Heroes of the American Revolution.

And yet the will to meet violence with violence apparently was not enough. The Black Panther Party had such resolve in abundance but met with legislative and social defeat. Disagreements as to the inclusion of Whites in the militant movement for Black liberation resulted in internecine strife and fed the government’s narrative that the Black Panthers were an explicit menace to society. The party’s leaders were killed, jailed or driven into exile, its social programs were marginalized, and its mission was sabotaged by government misinformation and extrajudicial persecution.

Like the early Black militias, the Panthers enjoyed occasional tactical victories but could not mobilize the mass of American society to effect lasting social change. Even the more broadly inclusive civil rights leaders were susceptible to imprisonment, exile and assassination. However, today’s relatively decentralized, app-connected movements enable even isolated participants to document abuses and to contribute virtually to mass resistance.

The effectiveness of the nonviolent Black Lives Matter movement in shining a spotlight on persistent racial violence gives cause for hope that American society can finally come to terms with painful and unjust elements of its past without threats to life and liberty. A similarly hopeful note was published in the Courier-Journal of Louisville, Kentucky, in 1876 as Reconstruction was running off the rails of civil discourse.

We of the South hope, in this election, to gain, after so many years of sorrow and tribulation, the status we lost when poor Abe Lincoln was assassinated. Had he lived, how many horrors might have been averted! He desired to see a general reconciliation, such as Mr. Tilden’s late letter depicts, and by the very means he so ably describes.

And here let me add that if the North will just give us the same government they desire to live under themselves, none but stock brokers, lobbyists and such cattle will ever think of asking for any more taxes to be laid to pay war claims, which, like our braves, are only resurrected for political effect, and not that the Republicans seriously think that we expect a dollar. I was a rebel soldier for four years, and I thought my cause was just. But “let bygones be bygones.” I am sick of war. All we people of the South want is a Government which we can live under at peace with our neighbor, be he white or black, blue or gray.

For more information on Black Life in America, Series 1 and 2, please contact Readex.