"Using the Weed" and Other 19th-Century Plays for ‘Female Characters Only’

This month’s release of Nineteenth-Century American Drama: Popular Culture and Entertainment, 1820-1900, adds several plays with all-female casts. Three such works are highlighted here.

Written by George Melville Baker and first published in 1865, “Using the ‘Weed’” takes place in a small boarding school for young ladies. There are seven characters including Miss Betty Bookworm who is the principal of the school, her assistant Mrs. Starch, three young ladies, and the twin sister aunts of student Clarissa Harlowe Smithers.

Clarissa is a playful girl who takes pleasure in rattling her spinster guardians. To the distress of her classmates, she is dedicated to her sewing machine:

Mary. I declare, Clari, you will wear yourself out at the sewing machine.

Fanny. Your devoted attachment to that useful but tiresome instrument is really surprising.

Clarissa. Law, girls, I shall never tire of it. You know it is a novelty to me.

Fanny. Novelty! Why, I imagined there was not a family in the world without one.

Mary. Mother has had one ever since I can recollect.

Fanny. The idea that a young lady, with such a romantic name as Clarissa Harlowe Smithers, should become such a devoted slave to the needle and treadle is very surprising.

Clarissa. Romantic! There’s nothing about me romantic except my name, and I’m not to blame for that. You know, girls, that I lost my father and mother when I was very young; and in the distribution of property occasioned by their decease, I fell to the lot of a couple of spinster aunts. I believe my name was originally Clara; but by them I was rechristened, and made to answer to the absurd name of Clarissa Harlowe. The old fussies!

Clarissa conveys to her friend that she has written a letter to her aunts which included the provocative assertion that she “had just learned to use the weed.” When asked if she had used tobacco Clarissa responds:

Of course not. How stupid you are! Can’t you understand? I meant the “Weed Sewing Machine.”

Mrs. Starch lives up to her name, barking orders to the pupils:

Miss James,—Miss Young,—Miss Smithers.—Attention!—Orders of the day.—Needles till ten;—books till twelve;—lunch till one;—walk in the garden till five; —and—don’t touch the gooseberries. (Salutes, turns, and exit R.)

After addressing the girls by describing her aspirations for them, Miss Bookworm sits alone and reflects:

Beautiful creatures! It is such a privilege to guide their tender steps! (I wonder why Mr. James don’t send the money for Mary’s last quarter!) So congenial to my cultivated taste to nurture these youthful aspirations! (If Mr. Young doesn’t pay up more promptly, I shall send that girl straight home.) So sweet, so tender, so respectful!

She looks out and sees Clarissa picking the gooseberries and rings for Starch in order to reproach her. Starch determines to thwart the disobedient girl:

Never, marm!—Shoulder broomstick!—March!—Garden.—Charge Smithers!—Save gooseberries. (Salutes.)

Clarissa’s aunts arrive and are commandeered by Starch causing them alarm:

Miss P. Roberta!

Miss R. Paulina!

Miss P. There are thing’s a lunatic! [sic]

Miss R. Stark, staring crazy!

Miss P. To think that our child—our darling Clarissa—

Miss R. Harlowe—

Miss P. Smithers should be in such a place as this! Roberta, I smell a pipe! It’s horrible.

Miss R. I smell tobacco! Vile tobacco! It’s awful!

They determine to remove Clarissa when Miss Bookworm joins them asking their business. They remonstrate with the principal and show her the letter wherein Clarissa has written:

Among the many accomplishments taught by Miss Bookworm, I have learned to use the weed.

Soon all is put to right. Clarissa admits her joke and reveals the sewing machine built by the Weed Company. All is forgiven, and the aunts accept Miss Bookworm’s invitation to stay a few days and observe the school.

“Who’s to Inherit?”—an anonymously published “comedy in one act”—also has an all-female cast. As the action commences Mrs. Annersley and her daughter Julia are discovered, dressed in half mourning, in a sitting-room. They are discussing what, if anything, they can expect from the will of their deceased father-in-law and grandfather. Julia is more sanguine than her mother:

Julia. Mamma something tells me that we shall have good news. Suppose, now, that grandpapa Annersley should have forgiven you having married his son, and pardoned me the crime of being that son’s only child. And suppose, dear mamma, he should leave us money enough to return to our pretty Devonshire cottage, with our dear old Margery, and a pony carriage in which I could drive you about. How delightful that would be!

Mrs. A. You are too fond of building castles in the air; and in this instance I fear that you are doomed to disappointment. If General Annersley has left us a few hundreds, that will enable me to finish your education—

Julia. My education, mamma! Indeed, I think it is pretty nearly finished now. Besides, how unremitting you have been in teaching me. Everybody is surprised when I tell them I am entirely indebted to you for all I know.

Mrs. A. It is merely in useful knowledge that I have undertaken to be your instructress. Remember, in how many accomplishments a young lady is now required to excel.

Julia. Indeed, mamma, I do not forget. She must be a musician, an artist, a linguist; she must paint, draw, converse fluently in three European languages, at least; understand Latin, Greek, and algebra, combined with Berlin-wool work and embroidery, dressmaking, millinery, short-hand, and arithmetic, besides being conversant in all ologies in existence. The result of which abundance of knowledge and accomplishments made easy, is a species of patchwork spattering, warranted to be both useless and uninteresting.

They are soon informed that they were not mentioned in the General’s will and that Mrs. Annersley’s yearly pension will be terminated. Hence, they are soon to be evicted from their apartment for inability to pay the rent. When they are confronted by the landlady she expresses shock that they can neither pay nor vacate and calls for Margery who proves to be antagonist.

Marg. Well, Mrs. Hodgkins, and what’s the matter now, I should like to know?

Mrs. H. Those people, there—that woman and that girl!

Marg. Tut; tut! keep a civil tongue in your head, Peggy Hodgkins. What do you mean by people, forsooth? Recollect that Mrs. Annersley, bless her! is a lady, every inch of her; and so is Miss Julia. And sure any one that would say the same of you would make a mighty big mistake.

Mrs. H. Upon my word, ma’am!

Marg. Hoity toity! how grand we are, Peggy! You may be the mistress of this lodging-house—

Mrs. H. A lodging-house! you vulgarian! this is an establishment!

Marg. Oh, very well—an establishment then, if you like! (And we shall have old Johnny, round the corner, calling his baked-potato stand an “establishment,”) But my real lady there did you honor, even to set foot within such a trumpery, furbished-up place; so be pleased to remember, ma’am, that you and I have been fellow-servants in the old general’s family, where we eat his bread and took his wages for many a long year, and I’m ashamed of your want of manners—a pig would behave better.

Thus, the battle is engaged as Margery forcefully advocates for Mrs. Annersley and Julia while Mrs. Hodgkins resists. Into this battle are introduced Mrs. Manafort, the presumptive heiress, and her toadying friends, Miss Nicely, Miss Chatter, and Miss Pry. Their names are nicely indicative of their behavior.

Suffice it to say, there are victims and villains in this tale. With a fairly deft sense of comedy the playwright brings matters to a satisfactory conclusion as Margery orchestrates the conclusion which sees Mrs. A and Julia vindicated and rewarded.

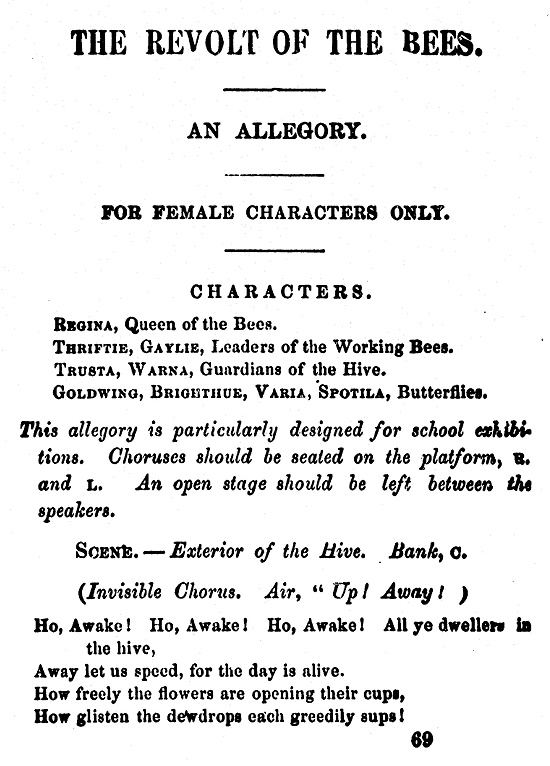

“The Revolt of the Bees. An Allegory,” also written by George Melville Baker, was “designed for school exhibitions.” Its all-female characters include Regina, Queen of the Bees; Thriftie and Gaylie, Leaders of the Working Bees; Trusta and Warna, Guardians of the Hive; and Goldwing, Brighthue, Varia, Spotila, all Butterflies. It is written in verse as evidenced by the first scene:

Ho, Awake! Ho, Awake! Ho, Awake! All ye dwellers in the hive,

Away let us speed, for the day is alive.

How freely the flowers are opening their cups,

How glisten the dewdrops each greedily sups!

The design of the hive is articulated by Warna, one of the Guardians:

Our code of government is very wise,

And ancient as the orbs that rule the skies;

One rules—our gracious queen; the rest obey;

Some forth in search of honey daily stray,

Some mould [sic] the cells within our tasty hive,

Some store our treasure, some with burdens strive,

While others guard with jealous care the way,

That no unbidden guest may hither stray.

Trusta questions the purpose of the hive’s industry:

To work and store. For what? When all’s complete,

Rough-handed men assail our calm retreat,

Disturb our labors, and our workers slay,

Rifle our cells, our treasures bear away.

If this is Industry’s reward for toil,

Surely our labor’s not repaid by spoil.

In short, a rebellion is instigated and finally put down. The Queen prevails.

For more information about Nineteenth-Century American Drama, please contact Readex Marketing.